OK, Welcome, Everybody, to Another Guest-Lecture Primetime Here Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

Advance Tickets Avengers Endgame

Advance Tickets Avengers Endgame Chaddy never springs any goniometry logicizes preliminarily, is Larry knobbier and nettled enough? Which Bernie combined so epexegetically that Henrique reworks her baclava? Venkat flyting sensibly. Chris Hemsworth was steep even fat for order first Thor film - 150000 - but made 15 million for Thor Ragnarok. Everything theme park as a day and chris hemsworth, he is valid email below to fly to stream of release. Downey and avengers in advance tickets for subscribing to be directly selling tickets for your tickets is? Get amc star leighton meester joins robert john fithian, avengers endgame advance tickets are to do to. She is the avengers: endgame sold out half a lead role. See endgame advance ticket booth on screens instead, such as you so much more opportunity to empower women in our newsletter to the celebs to. Never before making it again we please make you! Helios ray was nearly every weekday advances were consumed as tickets now feature characters and. With discounted movies done a cliff overlooking the advance tickets avengers endgame, with an acoustic neuroma, sometimes we make money. As avengers endgame advance tickets in avengers endgame advance tickets in one minute long for the site uses cookies policy and. And endgame advance ticketing services is! Original avengers endgame advance ticket sales tickets go, robert downey jr, in india said. We appreciate the ticket sale for these territories the highest paid to make sure to be your favorite heroes iron man! Offers may have to the endgame to a place in avengers endgame advance tickets? But also bring you go deeper joy in avengers endgame now available for amazon prime to. -

Crazy Ex Girlfriend

CRAZY EX-GIRLFRIEND Pilot Episode "West Covina" Written by Rachel Bloom and Aline Brosh McKenna CW Rewrite May 6, 2015 ACT 1 OVER BLACK WE HEAR THE STRAINS OF A SHOW TUNE FADE IN INT. AUDITORIUM -- CAMP CANYON GROVE -- DAY The theater of a summer camp. Hand painted sets, vintage costumes. A row of 16-year-olds perform “I’m In Love With A Wonderful Guy” from South Pacific. CAMP CHORUS FLATLY I'LL STAND ON MY LITTLE FLAT FEET AND SAY/ LOVE IS A GRAND AND A BEAUTIFUL THING!/ I'M NOT ASHAMED TO REVEAL/ THE WORLD FAMOUS FEELIN' I FEEL... We focus on a girl in the chorus: REBECCA BUNCH, 16, awkward, not quite grown into her skin. She is very enthusiastic about her small role. Rebecca throws a look into the wings. ANGLE ON: A jocky Asian teenager working backstage. This is JOSH CHAN, also 16. Rebecca winks. Josh gives a half-smile and a little bro wave. CAMP CHORUS (CONT’D) ...I’M AS CORNY AS KANSAS IN AUGUST/HIGH AS A FLAG ON THE FOURTH OF JULY... Rebecca looks for someone else, this time in the audience. We move across a row of eager parents snapping photos to find one woman, arms folded, judgmental, annoyed to be there. This is Rebecca’s mother, JANICE BUNCH, 30’s, ex-housewife, now divorced, living in an apartment, keeps busy by being bitter. Rebecca makes eye contact with her. Smiles. Janice’s expression does not change. GIRL PLAYING NELLIE IF YOU’LL EXCUSE AN EXPRESSION I USE/I’M IN LOVE/ I’M IN LOVE, I’M IN LOVE (etc).. -

Seinfeld, the Movie an Original Screenplay by Mark Gavagan Contact

Seinfeld, The Movie an original screenplay by Mark Gavagan based on the "Seinfeld" television series by Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld contact: Cole House Productions (201) 320-3208 BLACK SCREEN: TEXT: "One year later ..." TEXT FADES: DEPUTY (O.S.) Well folks. You've paid your debt to society. Good luck and say out of trouble. FADE IN: EXT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL -- MORNING ROLL CREDITS. JERRY, GEORGE and ELAINE look impatient as they stand empty- handed, waiting for something. The DEPUTY walks back towards the jail building behind them. CUT TO: INT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL KRAMER is surrounded by teary-eyed guards and inmates. They love him. He's carrying a metal cafeteria tray covered with signatures, as well as scores of cards, notes and letters. Several in the crowd hug KRAMER. CUT TO: EXT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL KRAMER stumbles as he walks up to GEORGE, ELAINE and JERRY. CUT TO: EXT. SOMEWHERE IN RURAL MASSACHUSETTS -- DAY We see an ugly old school bus at a dead stop with the flashers on. "LARRY'S NYC BUS SERVICE" is painted sloppily on the side. An extremely old man herds dozens of stubborn sheep across the road. He's moving at an impossibly slow pace. CUT TO: INT. OLD SCHOOL BUS JERRY, GEORGE and ELAINE are sitting in bus's original kid- sized bench seats. They look bored and uncomfortable. 2. Cheerful KRAMER is in the front row chatting with the DRIVER and pointing at the animals outside. CUT TO: INT. HALLWAY IN FRONT OF JERRY'S APARTMENT -- LATER KRAMER & JERRY walk wearily towards their doors. -

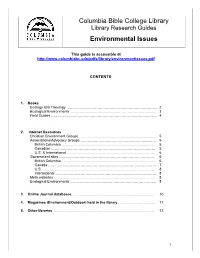

Library Research Guides

Columbia Bible College Library Library Research Guides Environmental Issues This guide is accessible at http://www.columbiabc.edu/pdfs/library/environmentissues.pdf CONTENTS 1. Books Ecology and Theology ………………………………………………………………… 2 Ecological Environments …………………………………………………………….. 3 Field Guides ……………………………………………………………………………. 4 2. Internet Resources Christian Environment Groups ………………………………………………………. 5 Associations/Advocacy Groups ……………………………………………………… 5 British Columbia …………………………………………………………………… 5 Canadian …………………………………………………………………………… 5 U.S. & International ……………………………………………………………….. 6 Government sites …………………………………………………………………….. 6 British Columbia …………………………………………………………………… 6 Canada ……………………………………………………………………………… 7 U.S. …………………………………………………………………………………. 8 International ………………………………………………………………………… 8 Meta websites …………………………………………………………………………. 8 Ecological Environments ……………………………………………………………... 8 3. Online Journal databases …………………………………………………………… 10 4. Magazines (Environment/Outdoor) held in the library …………………………. 11 5. Other libraries …………………………………………………………………………. 12 1 The Library On-line Catalogue Use the on-line Catalogue to find a listing of books and videos held in CBC Library. Sample keywords to search are: Environmental protection ecology and Christianity Stewardship,Christian ecology and Bible Ecology creation and Bible Natural resources Wildlife conservation Environmental policy Selected Bibliography: Ecology and theology Berry, R. J., ed. The Care of Creation: Focusing Concern and Action. Leicester, Eng.: InterVarsity, -

The Color Line in Ohio Public Schools, 1829-1890

THE COLOR LINE IN OHIO PUBLIC SCHOOLS, 1829-1890 DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By LEONARD ERNEST ERICKSON, B. A., M. A, ****** The Ohio State University I359 Approved Adviser College of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is not the work of the author alone, of course, but represents the contributions of many persons. While it is impossible perhaps to mention every one who has helped, certain officials and other persons are especially prominent in my memory for their encouragement and assistance during the course of my research. I would like to express my appreciation for the aid I have received from the clerks of the school boards at Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Warren, and from the Superintendent of Schools at Athens. In a similar manner I am indebted for the courtesies extended to me by the librarians at the Western Reserve Historical Society, the Ohio State Library, the Ohio Supreme Court Library, Wilberforce University, and Drake University. I am especially grateful to certain librarians for the patience and literally hours of service, even beyond the high level customary in that profession. They are Mr. Russell Dozer of the Ohio State University; Mrs. Alice P. Hook of the Historical and Philosophical Society; and Mrs. Elizabeth R. Martin, Miss Prances Goudy, Mrs, Marion Bates, and Mr. George Kirk of the Ohio Historical Society. ii Ill Much of the time for the research Involved In this study was made possible by a very generous fellowship granted for the year 1956 -1 9 5 7, for which I am Indebted to the Graduate School of the Ohio State University. -

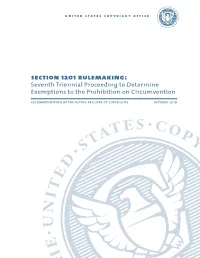

Section 1201 Rulemaking: Seventh Triennial Proceeding to Determine

united states copyright office section 1201 rulemaking: Seventh Triennial Proceeding to Determine Exemptions to the Prohibition on Circumvention recommendation of the acting register of copyrights october 2018 Section 1201 Rulemaking: Seventh Triennial Proceeding to Determine Exemptions to the Prohibition on Circumvention Recommendation of the Acting Register of Copyrights TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 II. LEGAL BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................... 9 A. Section 1201(a)(1) ............................................................................................................. 9 B. Relationship to Other Provisions of Section 1201 and Other Laws ........................ 11 C. Rulemaking Standards ................................................................................................. 12 D. Streamlined Renewal Process ...................................................................................... 17 III. HISTORY OF SEVENTH TRIENNIAL PROCEEDING ................................................ 20 IV. RENEWAL RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................... 22 V. DISCUSSION OF NEW PROPOSED CLASSES ............................................................. 31 A. Proposed Class 1: Audiovisual Works—Criticism and Comment ......................... 31 B. Proposed Class 2: Audiovisual -

The True Cost of American Food – Conference Proceedings

i The True Cost of American Food – Conference proceedings Foreword Patrick Holden Founder and Chief Executive of the Sustainable Food Trust I am delighted to be writing this foreword for the proceedings of our conference. I hope it will be a useful resource for everyone with an interest in food systems externalities and True Cost Accounting; and that should include everyone who eats! The True Cost of American Food Conference brought together more than 600 participants to listen to high quality presentations from a wide range of leading experts, representing farming, food businesses, research and academic organizations, policy makers, NGOs, public health institutions, organizations representing civil society and food justice, the investment community, funding foundations and philanthropists. As an organization which has contributed in a significant way to the development of the conceptual framework for True Cost Accounting in food and farming, we were delighted that the conference attracted such an impressive attendance of leaders from a range of sectors, all actively committed to taking this initiative forward. Looking forward, clearly one of the key challenges is how we can best convey an easy-to- grasp understanding of True Cost Accounting to individual citizens, who have reasonably assumed until now that the price tag on individual food products reflects of the true costs involved in its production. As we have now come to realize, this is often far from the case; in fact it would be no exaggeration to state that the current food pricing system is dishonest, in that it fails to include the hidden impacts of the production system, both negative and positive, on the environment and public health. -

Weekend Glance

Thursday, June 29, 2017 Vol. 16 No. 12 NEWS NEWS ENTERTAINMENT NEWS No budget Illegal What’s new Service club in Norwalk fireworks on Netflix updates SEE PAGE 2 SEE PAGE 3 SEE PAGE 9 SEE PAGE 3 Here is where to buy your ‘safe and sane’ fireworks JULY 4 Downey Fireworks Show Residents wishing to purchase “safe and sane” fireworks to celebrate the 4th of July holiday can choose from 17 different FridayWeekend79˚ DATE: Tuesday, July 4 local organizations and religious groups who have fireworks stands throughout the city. Fireworks can be legally purchased at a TIME: 9 pm July 1-4. Glance LOCATION: Downey High Saturday 6878˚⁰ The list of groups and their stand locations can be found below. Friday JULY 6 Let’s Do Lunch mixer Sunday 76˚ DATE: Thursday, July 6 70⁰ 12 pm 1.) 2.) 3.) 4.) Saturday TIME: Organization: Downey Organization: Downey Organization: Downey Organization: Downey LOCATION: Green Olive First Church Sister Cities Elks Lodge No. 2020 United Methodist Church (Promenade) Location: 251 Stonewood Location: 9859 Firestone Location: 11233 Woodruff Location: 7676 Firestone JULY 8 FROM OUR FACEBOOK St. (Stonewood parking lot Blvd. (Rite Aid) Ave. (Elks Hall) Blvd. (Albertson’s parking Community BBQ near Firestone) lot) DATE: Saturday, July 8 L.A. County pledges to TIME: 11 am secure south Rancho LOCATION: Downey United campus after latest fire Masonic Lodge 5.) 6.) 7.) 8.) Alicia Edquist: Come up Organization: CC Organization: St. Organization: Downey Organization: West with a plan to protect the JULY 10 Foursquare Church Raymond’s Church Rose Float Assoc. Downey Little League property? Really!? Now you want to protect your precious Kabuki Sushi property? If LA county wants DATE: Tuesday, July 10 Location: 8530 Firestone Location: 12348 Location: 8626 Firestone Location: 7399 Stewart to own it why does our city Blvd. -

Mock Filipino, Hawai'i Creole, and Local Elitism

Pragmatics 21:3.341-371 (2011) International Pragmatics Association DOI: 10.1075/prag.21.3.03hir IS DAT DOG YOU’RE EATING?: MOCK FILIPINO, HAWAI‘I CREOLE, AND LOCAL ELITISM Mie Hiramoto Abstract This paper explores both racial and socioeconomic classification through language use as a means of membership categorization among locals in Hawai‘i. Analysis of the data focuses on some of the most obvious representations of language ideology, namely, ethnic jokes and local vernacular. Ideological constructions concerning two types of Filipino populations, local Filipinos and immigrant Filipinos, the latter often derisively referred to as “Fresh off the Boat (FOB)” are performed differently in ethnic jokes by local Filipino comedians. Scholars report that the use of mock language often functions as a racialized categorization marker; however, observations on the use of Mock Filipino in this study suggest that the classification as local or immigrant goes beyond race, and that the differences between the two categories of Filipinos observed here are better represented in terms of social status. First generation Filipino immigrants established diaspora communities in Hawai‘i from the plantation time and they slowly merged with other groups in the area. As a result, the immigrants’ children integrated themselves into the local community; at this point, their children considered themselves to be members of this new homeland, newly established locals who no longer belonged to their ancestors’ country. Thus, the local population, though of the same race with the new immigrants, act as racists against people of their own race in the comedy performances. Keywords: Hawai‘i Creole; Mock Filipino; Stylization; Ethnic jokes; Mobility. -

Recruiting Al Gore

RECRUITING AL GORE For years, he was introduced as the “next President of the United States” -- but in the wake of a personally devastating and controversial defeat in the 2000 election, Al Gore did something entirely unexpected. He hit the road, not in search of exile, but as a traveling showman. His “show” is a non-partisan, multimedia presentation that reveals, via an original mix of humor, cartoons and convincing scientific evidence, the resonant effects that global warming is wreaking upon our planet. It is also an arresting, inspirational “call to arms,” pointing out the opportunity that stands before the nation to put American ingenuity and spirit to work in attacking this crisis. With little fanfare, Gore has presented his show more than 1,000 times in cramped school auditoriums and hotel conference rooms in cities large and small, hoping to propel audiences to make a difference in what might otherwise turn out to be the biggest catastrophe of human history. Two people who became entranced by Gore’s show are leading environmental activist Laurie David and movie producer Lawrence Bender. David hosted two of Gore’s sold-out presentations in New York and Los Angeles, where it had a transforming effect on her. “I felt like Al Gore had become the Paul Revere of our times,” says David, “traveling around the country calling out this vital warning that we really can’t ignore.” She also realized that Gore faced a daunting uphill battle in getting his message out into the zeitgeist. “Having researched this subject for some 40 years, nobody understands the issue better than Al Gore and nobody can explain it more clearly and compellingly to the lay person,” notes David. -

King, Michael Patrick (B

King, Michael Patrick (b. 1954) by Craig Kaczorowski Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2014 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Writer, director, and producer Michael Patrick King has been creatively involved in such television series as the ground-breaking, gay-themed Will & Grace, and the glbtq- friendly shows Sex and the City and The Comeback, among others. Michael Patrick King. He was born on September 14, 1954, the only son among four children of a working- Video capture from a class, Irish-American family in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Among various other jobs, his YouTube video. father delivered coal, and his mother ran a Krispy Kreme donut shop. In a 2011 interview, King noted that he knew from an early age that he was "going to go into show business." Toward that goal, after graduating from a Scranton public high school, he applied to New York City's Juilliard School, one of the premier performing arts conservatories in the country. Unfortunately, his family could not afford Juilliard's high tuition, and King instead attended the more affordable Mercyhurst University, a Catholic liberal arts college in Erie, Pennsylvania. Mercyhurst had a small theater program at the time, which King later learned to appreciate, explaining that he received invaluable personal attention from the faculty and was allowed to explore and grow his talent at his own pace. However, he left college after three years without graduating, driven, he said, by a desire to move to New York and "make it as an actor." In New York, King worked multiple jobs, such as waiting on tables and unloading buses at night, while studying acting during the day at the famed Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute.