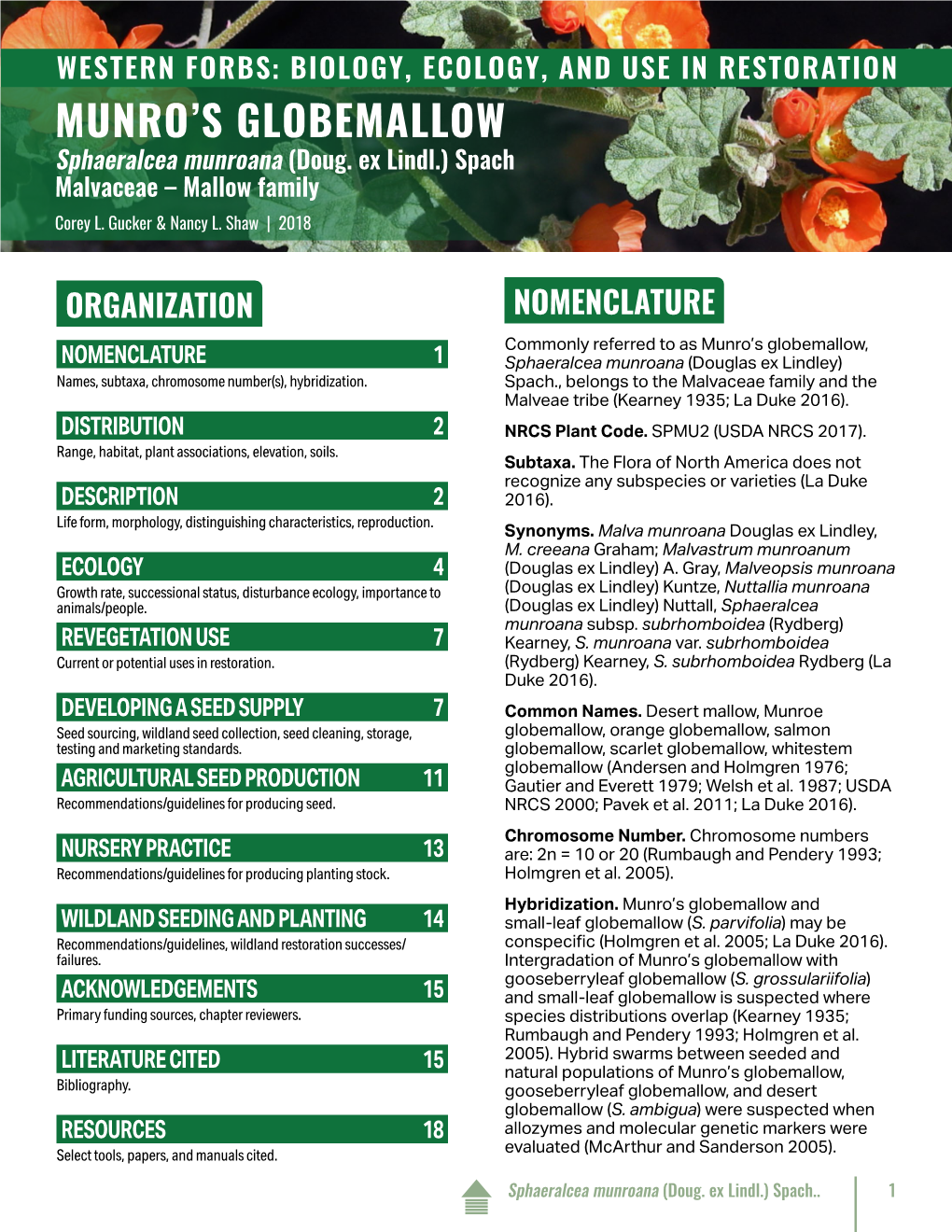

Munro's Globemallow (Sphaeralcea Munroana)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOOSEBERRYLEAF GLOBEMALLOW Sphaeralcea Grossulariifolia (Hook

GOOSEBERRYLEAF GLOBEMALLOW Sphaeralcea grossulariifolia (Hook. & Arn.) Rydb. Malvaceae – Mallow family Corey L. Gucker & Nancy L. Shaw | 2018 ORGANIZATION NOMENCLATURE Sphaeralcea grossulariifolia (Hook. & Arn.) Names, subtaxa, chromosome number(s), hybridization. Rydb., hereafter referred to as gooseberryleaf globemallow, belongs to the Malveae tribe of the Malvaceae or mallow family (Kearney 1935; La Duke 2016). Range, habitat, plant associations, elevation, soils. NRCS Plant Code. SPGR2 (USDA NRCS 2017). Subtaxa. The Flora of North America (La Duke 2016) does not recognize any varieties or Life form, morphology, distinguishing characteristics, reproduction. subspecies. Synonyms. Malvastrum coccineum (Nuttall) A. Gray var. grossulariifolium (Hooker & Arnott) Growth rate, successional status, disturbance ecology, importance to animals/people. Torrey, M. grossulariifolium (Hooker & Arnott) A. Gray, Sida grossulariifolia Hooker & Arnott, Sphaeralcea grossulariifolia subsp. pedata Current or potential uses in restoration. (Torrey ex A. Gray) Kearney, S. grossulariifolia var. pedata (Torrey ex A. Gray) Kearney, S. pedata Torrey ex A. Gray (La Duke 2016). Seed sourcing, wildland seed collection, seed cleaning, storage, Common Names. Gooseberryleaf globemallow, testing and marketing standards. current-leaf globemallow (La Duke 2016). Chromosome Number. Chromosome number is stable, 2n = 20, and plants are diploid (La Duke Recommendations/guidelines for producing seed. 2016). Hybridization. Hybridization occurs within the Sphaeralcea genus. -

A New Large-Flowered Species of Andeimalva (Malvaceae, Malvoideae) from Peru

A peer-reviewed open-access journal PhytoKeys 110: 91–99 (2018) A new large-flowered species of Andeimalva... 91 doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.110.29376 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://phytokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A new large-flowered species of Andeimalva (Malvaceae, Malvoideae) from Peru Laurence J. Dorr1, Carolina Romero-Hernández2, Kenneth J. Wurdack1 1 Department of Botany, MRC-166, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, USA 2 Missouri Botanical Garden Herbarium, William L. Brown Center, P.O. Box 299, Saint Louis, MO 63166-0299, USA Corresponding author: Laurence J. Dorr ([email protected]) Academic editor: Clifford Morden | Received 28 August 2018 | Accepted 11 October 2018 | Published 5 November 2018 Citation: Dorr LJ, Romero-Hernández C, Wurdack KJ (2018) A new large-flowered species ofAndeimalva (Malvaceae: Malvoideae) from Peru. PhytoKeys 110: 91–99. https://doi.org/10.3897/phytokeys.110.29376 Abstract Andeimalva peruviana Dorr & C.Romero, sp. nov., the third Peruvian endemic in a small genus of five species, is described and illustrated from a single collection made at high elevation on the eastern slopes of the Andes. Molecular phylogenetic analyses of nuclear ribosomal ITS sequence data resolve a group of northern species of Andeimalva found in Bolivia and Peru from the morphologically very different south- ern A. chilensis. The new species bears the largest flowers of anyAndeimalva and is compared with Bolivian A. mandonii. A revised key to the genus is presented. Keywords Andeimalva, Andes, Malvaceae, Malvoideae, Peru, phylogeny Introduction The genus Andeimalva J.A. Tate (Malvaceae, Malvoideae) was created to accommo- date four species found in the Andes of South America from northern Peru to central Chile and includes three species previously placed in Tarasa Phil. -

Review and Advances in Style Curvature for the Malvaceae Cheng-Jiang Ruan*

® International Journal of Plant Developmental Biology ©2010 Global Science Books Review and Advances in Style Curvature for the Malvaceae Cheng-Jiang Ruan* Key Laboratory of Biotechnology & Bio-Resources Utilization, Dalian Nationalities University, Dalian City, Liaoning 116600, China Correspondence : * [email protected] ABSTRACT The flowers of the Malvaceae with varying levels of herkogamy via style curvature have long intrigued evolutionary botanists. This review covers the flower opening process, approach herkogamy, style curvature and character evolution based on molecular phylogenetic trees, adaptive significances of style curvature and the mating system in some portions of the genera in this family. Hermaphroditic flowers of some species have showy petals and pollen and nectar rewards to pollinators. Approach herkogamy, in which stigmas are located on the top of a monadelphous stamen, has evolved as a mechanism to reduce the frequency of intra-floral self-pollination or the interference between male-female organs. Protandrous or monochogamous flowers in the fields open at about 5-7 days and 1-2 days respectively, and pollination is conducted by insects and birds. Interestingly, un-pollinated styles in some species curve when pollination fails. According to our observations and published or internet data, this curvature occurs in 23 species distributed in eight genera of four tribes (Malvavisceae, Ureneae, Hibisceae, Malveae) and appears to have evolved at least eight times. A shift to use style curvature is associated with a shift to annual or perennial herbs, and an unpredictable pollinator environment is likely an important trigger for this evolution. The adaptive significances of style curvature in the Malvaceae include delayed selfing, promotion of outcrossing or reduction in intrafloral male-female interference, sometimes two or three of which simultaneously occur in style curvature of one species (e.g., Kosteletzkya virginica). -

General View of Malvaceae Juss. S.L. and Taxonomic Revision of Genus Abutilon Mill

JKAU: Sci., Vol. 21 No. 2, pp: 349-363 (2009 A.D. / 1430 A.H.); DOI: 10.4197 / Sci. 21-2.12 General View of Malvaceae Juss. S.L. and Taxonomic Revision of Genus Abutilon Mill. in Saudi Arabia Wafaa Kamal Taia Alexandria University, Faculty of Science, Botany Department, Alexandria, Egypt [email protected] Abstract. This works deals with the recent opinions about the new classification of the core Malvales with special reference to the family Malvaceae s.l. and the morphological description and variations in the species of the genus Abutilon Mill. Taxonomical features of the family as shown in the recent classification systems, with full description of the main divisions of the family. Position of Malvaceae s.l. in the different modern taxonomical systems is clarified. General features of the genus Abutilon stated according to the careful examination of the specimens. Taxonomic position of Abutilon in the Malvaceae is given. Artificial key based on vegetative morphological characters is provided. Keywords: Abutilon, Core Malvales, Eumalvaceae, Morpholog, Systematic Position, Taxonomy. General Features of Family Malvaceae According to Heywood[1] and Watson and Dallwitz[2] the plants of the family Malvaceae s.s. are herbs, shrubs or trees with stipulate, simple, non-sheathing alternate or spiral, petiolate leaves usually with palmate vennation (often three principal veins arising from the base of the leaf blade). Plants are hermaphrodite, rarely dioecious or poly-gamo- monoecious with floral nectarines and entomophilous pollination. Flowers are solitary or aggregating in compound cymes, varying in size from small to large, regular or somewhat irregular, cyclic with distinct calyx and corolla. -

Chromosome Numbers and Evolution in Anoda and Periptera (Malvaceae) David M

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 11 | Issue 4 Article 8 1987 Chromosome Numbers and Evolution in Anoda and Periptera (Malvaceae) David M. Bates Cornell University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Bates, David M. (1987) "Chromosome Numbers and Evolution in Anoda and Periptera (Malvaceae)," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 11: Iss. 4, Article 8. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol11/iss4/8 ALISO 11(4), 1987, pp. 523-531 CHROMOSOME NUMBERS AND EVOLUTION IN ANODA AND PERIPTERA (MALVACEAE) DAVID M. BATES L. H. Bailey Hortorium, Cornell University Ithaca, New York 14853-4301 A BSTRACT Relationships within and between the principally North American, malvaceous genera Anoda and Periptera are assessed through analysis of chromosomal and hybridization data. Chromosome numbers are reported for ten species of Anoda and one of Periptera, and observations on meiosis in hybrid and non hybrid plants are presented. The results indicate: I) that Anoda and Periptera are closely related and occupy a relatively isolated position in the tribe Malveae, 2) that speciation in Anoda has occurred primarily at the diploid level, n = IS , although A. crenatijlora is tetraploid and A. cristata includes diploids, tetraploids, and hexapJoids, and 3) that A. thurberi and Periptera form a lineage based on n = 13, which probably was derived from Anoda sect. Liberanoda or its progenitors. Key words: Malvaceae, Anoda, Periptera, chromosomes, hybrids, evolution. INTRODUCTION Anoda Cav., which includes 23 species primarily of Mexico (Fryxell1987), and Periptera DC., which is composed of four Mexican species (Fryxell 1974, 1984, 1987), are distinguished from each other primarily by characters that reflect modes of pollination. -

Malva Subovata Subsp. Bicolor, Comb. & Stat. Nov. (Malvaceae)

Ann. Bot. Fennici 47: 312–314 ISSN 0003-3847 (print) ISSN 1797-2442 (online) Helsinki 30 August 2010 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2010 Malva subovata subsp. bicolor, comb. & stat. nov. (Malvaceae) Duilio Iamonico Via dei Colli Albani 170, IT-00179 Rome, Italy (e-mail: [email protected]) Received 28 May 2009, revised version received 26 June 2009, accepted 29 June 2009 Iamonico, D. 2010: Malva subovata subsp. bicolor, comb. & stat. nov. (Malvaceae). — Ann. Bot. Fennici 47: 312–314. The name Malva subovata (DC.) Molero & J.M. Monts. subsp. bicolor (Rouy) Iamon- ico, comb. & stat. nov. (Malvaceae) is proposed according to current generic concepts in the tribe Malveae. Key words: Lavatera, new combination, nomenclature Recent morphological and molecular studies Lavatera is limited to the species included in the (e.g. Judd & Manchester 1997, Bayer et al. “Lavateroid clade” as defined by Ray (1995). As 1999) showed that some of the formerly rec- a result of the studies of Ray (1995), several spe- ognized families of the order Malvales are not cies of Lavatera were transferred to Malva (Ray monophyletic; consequently, nine subfamilies of 1998, Banfi et al. 2005, Molero & Montserrat the family Malvaceae were recognized (Bayer et 2005, 2006). al. 1999, Bayer & Kubitzki 2003). In their taxonomical notes, Molero and The subfamily Malvoideae comprises four Montserrat (2005, 2006) showed that the name tribes: Gossypieae, Hibisceae, Kydieae and Malva africana (Cav.) Soldano, Banfi & Galasso, Malveae (Bayer & Kubitzki 2003). The tribe chosen by Banfi et al. (2005) for Lavatera mar- Malveae includes about 70 genera (about 1000 itima Gouan, is illegitimate under Art. -

Foliar Epidermal Anatomy and Pollen Morphology of the Genera Alcea and Althaea (Malvaceae) from Pakistan

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURE & BIOLOGY ISSN Print: 1560–8530; ISSN Online: 1814–9596 09–331/MHB/2010/12–3–329–334 http://www.fspublishers.org Full Length Article Foliar Epidermal Anatomy and Pollen Morphology of the Genera Alcea and Althaea (Malvaceae) from Pakistan NIGHAT SHAHEEN1, MIR AJAB KHAN, GHAZALAH YASMIN, MUHAMMAD QASIM HAYAT, SHAKIRA MUNSIF AND KHALID AHMAD Department of Plant Sciences, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 1Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Foliar epidermal anatomy and palynology of the four species belonging to two genera, Alcea L. and Althaea L. of family Malvaceae from Pakistan were studied and compared in detail both by light microscopy (LM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Leaves were amphistomatic and amphitrichomic with higher frequency of both stomata and trichomes on the abaxial surface. Three main types of glandular and eglandular trichomes were observed. Alcea rosea and A. lavateraeflora could be delimited by the characteristic features of their stellate trichomes. Palynological studies revealed the presence of apolar, pantoporate and echinate pollen. Character of spine index was used for the first time to describe Malvaceous pollen and is found of significant taxonomic importance. Artificial keys are given for all studied taxa based on foliar epidermal anatomical and palynomorphological features. © 2010 Friends Science Publishers Key Words: Foliar anatomy; Palynology; Malvaceae; Alcea; Althaea INTRODUCTION 1977; Adedeji & Dloh, 2004; Celka et al., 2006) but surprisingly no comprehensive report exists on the Both Althaea and Alcea are closely related genera and quantitative characteristics of epidermal structure in Alcea, have been fused together in the past, but up to date opinion Althaea and foliar epidermal studies are totally missing regards the two genera as clearly distinct genera (Abedin, from the taxonomic literature of Pakistan therefore one of 1979). -

Taxonomic Studies on Some Members of the Genus Abutilon Mill

American Journal of Plant Sciences, 2021, 12, 199-220 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ajps ISSN Online: 2158-2750 ISSN Print: 2158-2742 Taxonomic Studies on Some Members of the Genus Abutilon Mill. (Malvaceae) Dhafer A. Alzahrani1*, Enas J. Albokhari1,2, Abrar Khoj1 1Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 2Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia How to cite this paper: Alzahrani, D.A., Abstract Albokhari, E.J. and Khoj, A. (2021) Tax- onomic Studies on Some Members of the The relationship between six Abutilon species was examined using different Genus Abutilon Mill. (Malvaceae). Ameri- taxonomic investigation tools. The investigation was carried out using mor- can Journal of Plant Sciences, 12, 199-220. phological and numerical studies. Fresh materials of Abutilon species were https://doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2021.122012 collected from different localities in Saudi Arabia during 2018 and 2019. Nu- Received: January 10, 2021 merical analysis was based on the Principle Coordinates, the Principle Com- Accepted: February 23, 2021 ponent and the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Algorithm Published: February 26, 2021 Clustering. The results indicated that there were significant differences based Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and on the morphological characters especially in the leaves, fruits and flowers Scientific Research Publishing Inc. features. Morphometric studies revealed that the six species of Abutilon This work is licensed under the Creative clearly separated in all different analysis. Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Keywords Open Access Taxonomy, Malvaceae, Abutilon, Morphological Characters, Morphometric Analysis, UPGMA, PCoA, PCA 1. -

Identifying Abutilon Parishii (Malvaceae) and Similar Species in Arizona and Sonora

McNair, D.M., J. Fox, R. Lindley, S.D. Carnahan, M.E. Taylor, and E. Makings. 2018. Identifying Abutilon parishii (Malvaceae) and similar species in Arizona and Sonora. Phytoneuron 2018-84: 1–12. Published 20 December 2018. ISSN 2153 733X IDENTIFYING ABUTILON PARISHII (MALVACEAE) AND SIMILAR SPECIES IN ARIZONA AND SONORA DANIEL M. MCNAIR WestLand Resources, Inc. Tucson, Arizona [email protected] JANET FOX Tucson, Arizona RIES LINDLEY University of Arizona Herbarium (ARIZ) Tucson, Arizona SUSAN D. CARNAHAN University of Arizona Herbarium (ARIZ) Tucson, Arizona MARK E. TAYLOR United States Forest Service, Tonto National Forest ELIZABETH MAKINGS Arizona State University Vascular Plant Herbarium (ASU) Tempe, Arizona ABSTRACT We provide a visual aid for identifying Abutilon parishii along with similar genera and species in the mallow family (Malvaceae) that occur in Arizona and Sonora. The primary species featured are Abutilon mollicomum , A. palmeri , A. parishii , A. reventum , and A. wrightii , with briefer coverage provided for A. abutiloides , A. incanum , A. parvulum , A. theophrasti , Anoda abutiloides , and Herissantia crispa . Three of the species featured, A. parishii , A. reventum , and Anoda abutiloides , are of conservation concern. Abutilon (Malvaceae) species in North and Central America are typically recognizable as woody or herbaceous perennial shrubs with leaves that are simple, alternate, long-petiolate, cordate- based, toothed, and stellate-haired. Flowers are axillary or in panicles with yellow to orange petals; schizocarps typically contain 4–10 (25) mericarps (Fryxell 1988; Fryxell & Hill 2015). Similar New World genera include Anoda , Bakeridesia , Callianthe , Herissantia , Pseudabutilon , and Sida (Fryxell 1988, 1997a; Donnell et al. 2012). Various Abutilon species are widely cultivated (Austin 2004; Fryxell & Hill 2015; Saini et al. -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- MAGNOLIACEAE

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- MAGNOLIACEAE MAGNOLIACEAE (Magnolia Family) A family of about 7 genera and 165 species, trees and shrubs, tropical and warm temperate, of e. and se. Asia, and from e. North America south through West Indies and Central America to Brazil. References: Hardin (1972); Hardin & Jones (1989)=Z; Meyer in FNA (1997); Nooteboom in Kubitzki, Rohwer, & Bittrich (1993); Kim et al. (2001). 1 Leaves about as broad as long, (2-) 4 (-8)-lobed; fruit a 2-seeded, indehiscent samara; [subfamily Liriodendroideae] ........ ...................................................................................... Liriodendron 1 Leaves longer than broad, not lobed (in some species the leaves auriculate-cordate basally); fruit a cone-like aggregate, each follicle dehiscing to reveal the scarlet seed, at first connected to the follicle by a thread-like strand; [subfamily Magnolioideae] ..........................................................................................Magnolia Liriodendron Linnaeus (Tulip-tree) A genus of 2 species, trees, relictually distributed, with L. tulipifera in e. North America and L. chinense (Hemsley) Sargent in c. China and n. Vietnam. References: Nooteboom in Kubitzki, Rohwer, & Bittrich (1993); Weakley & Parks (in prep.), abbreviated as Z. 1 Leaves large, 4-8-lobed, the terminal lobes acute; [plants of the Mountains, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain (especially brownwater rivers and mesic bluffs and slopes)] . L. tulipifera var. tulipifera 1 Leaves small, 0-4-lobed, the terminal lobes obtuse to broadly rounded; [plants of the Coastal Plain, especially fire-maintained, acidic, and peaty sites] .................................................................L. tulipifera var. 1 Liriodendron tulipifera Linnaeus var. tulipifera, Tulip-tree, Yellow Poplar, Whitewood. Mt, Pd, Cp (GA, NC, SC, VA): mesic forests, cove forests in the Mountains to at least 1500m in elevation, bottomland forests and swamps; common. -

Acta Botanica Brasilica - 34(2): 301-311

Acta Botanica Brasilica - 34(2): 301-311. April-June 2020. doi: 10.1590/0102-33062019abb0293 Fruits of neotropical species of the tribe Malveae (Malvoideae – Malvaceae): macro- and micromorphology Fernanda de Araújo Masullo1 , Sanny Ferreia Hadibe Siqueira2 , Claudia Franca Barros1, 3 , Massimo G. Bovini3 and Karen L. G. De Toni1, 3* Received: August 26, 2019 Accepted: February 11, 2020 . ABSTRACT Fruit morphology of the tribe Malveae has been discussed since the first taxonomic classifications of Malvaceae. The fruits are schizocarps, with some genera possessing an endoglossum. Besides morphological variation in the endoglossum, other differences include the number seeds per locule and ornamentation of the exocarp. An in-depth study of the fruit morphology of Malveae is essential to gain insight into the relationships among taxa of the tribe. Therefore, the present study aimed to describe the fruit morphology of Malveae, including micromorphology, variation in endoglossum structure and arrangement of seeds in the locule, to comprehensively evaluate the systematic relationships among its contained taxa. The results indicate morphological variation in fruit of various genera with regard to the number of mericarps, degree of dehiscence, relationship between calyx and fruit and their relative sizes, number and morphology of spines, number of seeds per locule, presence or absence of an endoglossum, presence and types of trichomes in exocarp and endocarp, and shape and presence of trichomes in the testa of seeds. Despite the morphological proximity of taxa, there are distinct combinations of characters that define some genera, and when one or more characters overlap, joint analysis makes it possible to clarify existing relationships. Keywords: endoglossum, mericarps, pericarp, schizocarp, seeds have schizocarp fruits. -

Phylogenetic Relationships of Malvatheca (Bombacoideae and Malvoideae; Malvaceae Sensu Lato) As Inferred from Plastid DNA Sequences

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences Papers in the Biological Sciences 2004 Phylogenetic Relationships of Malvatheca (Bombacoideae and Malvoideae; Malvaceae sensu lato) as Inferred from Plastid DNA Sequences David A. Baum University of Wisconsin - Madison Stacey DeWitt Smith University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Alan Yen Harvard University Herbaria, William S. Alverson The Field Museum (Chicago, Illinois) Reto Nyffeler Harvard University Herbaria, See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscifacpub Part of the Life Sciences Commons Baum, David A.; Smith, Stacey DeWitt; Yen, Alan; Alverson, William S.; Nyffeler, Reto; Whitlock, Barbara A.; and Oldham, Rebecca L., "Phylogenetic Relationships of Malvatheca (Bombacoideae and Malvoideae; Malvaceae sensu lato) as Inferred from Plastid DNA Sequences" (2004). Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences. 110. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscifacpub/110 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors David A. Baum, Stacey DeWitt Smith, Alan Yen, William S. Alverson, Reto Nyffeler, Barbara A. Whitlock, and Rebecca L. Oldham This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ bioscifacpub/110 American Journal of Botany 91(11): 1863±1871. 2004. PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF MALVATHECA (BOMBACOIDEAE AND MALVOIDEAE;MALVACEAE SENSU LATO) AS INFERRED FROM PLASTID DNA SEQUENCES1 DAVID A. BAUM,2,3,5 STACEY DEWITT SMITH,2 ALAN YEN,3,6 WILLIAM S.