Reinventing the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jersey City Bus Study

JERSEY CITY BUS STUDY FINAL REPORT Prepared By New Jersey Transit Bus Service Planning Department November 2, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Executive Summary 1 I. Introduction 5 II. Study Objectives 5 III. Information Collection 6 IV. Basic Data 7 Jersey City Local Bus Service Map Following 7 V. Assessment of Existing Bus Service 8 VI. General Priorities 12 VII. Specific Recommendations 17 VIII. Phasing the Recommendations – A Blueprint for the Near Future 27 Compiled Appendices Following 31 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Jersey City Local Bus Study was written in response to concerns that portions of the Jersey City local bus network were collapsing as private carriers cut back or eliminated service in its entirety. NJ TRANSIT, the City of Jersey City, the County of Hudson, and the North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority funded the work effort. It was prepared by the Bus Service Planning staff at NJ TRANSIT with input from a Technical Advisory Committee composed of individuals representing the funding agencies. The focus of the study is on short-term improvements primarily in Jersey City that need to be implemented as resources such as operating funds and equipment become available. This report describes the existing bus service in Hudson County and presents short- term recommendations for changes and improvements to the local bus system, both in terms of general and systemic issues as well as specific route-by-route actions. More than three dozen action items were identified to improve existing bus operations. These items range from route-specific service adjustments to providing for more ticket and pass sales outlets either by vendors or the installation of ticket vending machines (TVMs). -

FACILITIES LOCATOR DOREMUS AVENUE OVERWEIGHT CORRIDOR the Port Is a Facility of the Port Authority of NY & NJ 1/20

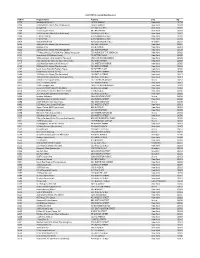

PORT NEWARK/ELIZABETH BUILDING LOCATION CHART BLDG # KEY BLDG # KEY 111 ........................ 3-A 340 ........................ 1-B 118 ........................ 3-C 350 ........................ 2-C W AREHOUSE PL 120 ........................ 3-A 365 ........................ 2-D 122 ........................ 3-C 371 ........................ 2-C 132 W CRANE 123 ...................... 3-AB 390 ........................ 2-D OUTER PORT ST K9 TRAILERS 126 ........................ 3-B 391 ........................ 2-D INNER PORT ST A Y ST Y 131 ........................ 3-B 392 ........................ 2-D VIKING ST 132 ........................ 3-B 400 ........................ 2-A 133-134 ................ 3-B 401 ........................ 3-B 135 ........................ 3-C 1070 ...................... 5-B 137 ........................ 3-B 1100 ...................... 7-B 138 ........................ 2-A 1121 ...................... 6-B 142 ........................ 3-C 1130 ...........7-AB/8-AB 143 ........................ 3-C 1131 ...................... 8-A 147 ........................ 3-A 1140 .................... 7-AB 148 ........................ 3-B 1150 ...........6-AB/7-AB RED HOOK TRUCK ENTRANCE 150 ........................ 3-C 1155 ...................... 6-B 151 ........................ 3-A 1156 ...................... 6-B ENTRANCE 154 ........................ 3-C 1160 ...................... 7-B 155 ........................ 3-C 1170 ...................... 7-B 189T ENTRANCE 164 ........................ 3-C 1180 ...................... 7-B 173A -

Rethinknyc+2020-08-20A.Pdf

ReThinkNYC Requests that ReThinkNYC Proposals be Treated as Alternatives to be Studied ReThinkNYC • New York, NY • August,20 2020 Reimagined Penn Station’s Main Hall. Digital Rendering by NOVA Concepts. “The Pennsylvania Station in New York is like some vast basilica of old that towers above the terror of the dark as bulwark and protection to the soul.” Langston Hughes 1. Introduction: ReThinkNYC Requests that ReThinkNYC Proposals be Treated as Alternatives to be Studied 7th Avenue Facade rendering by Jeff Stikeman RethinkNYC submits the following supplemental statement and proposals to their July 20, 2020 preliminary written and verbal submissions which were made in response to the Empire State Development Corps Draft Scope of Work (“DSOW”) and request for Public Comment. RethinkNYC asks that this supplementary submission, which incorporates and adds to the prior submissions(with any changes noted), be read as a unified document. RethinkNYC requests that the proposals submitted today be considered as an “alternative(s) to be studied” as set forth on page 53 of the DSOW. While RethinkNYC’s more specific criticism’s are set forth immediately below, RethinkNYC’s overarching criticism and reason for sponsoring alternatives is that the proposed Empire State Complex fails to sufficiently unlock the potential that a modernized Penn Station and transit network would have on the economy, the region and nation’s ecology, aesthetics, fair housing and accessability to the job market, among many other advantages. While the DSOW acknowledges other infrastructure projects — Gateway, Sunnyside Yards and the Port Authority Bus Terminal — it does not coordinate or harmonize these proposals in a way that maximizes their impacts for the region. -

DIRECTIONS by SUBWAY: F Train to East Broadway Take Rutgers St./Madison St

DIRECTIONS BY SUBWAY: F Train to East Broadway Take Rutgers St./Madison St. exit from station - Exit Walk east on Rutgers Street towards the water. Turn left on South Street heading north. Once you approach the Dept of Sanitation (on your right), Pier 36 is adjacent on the north side of Sanitation. DIRECTIONS BY CAR: From FDR Drive - Southbound: FDR Drive South to Exit 3, towards South St/Manhattan Bridge. Stay straight to go onto FDR Drive. FDR Drive becomes South Street. Pier 36 is located at the intersection of South Street and Montgomery Street From FDR Drive - Northbound: South Street north (under the FDR highway), past the South Street Seaport (do not go on the FDR Drive). Continue north on South Street (under the Manhattan Bridge, Pathmark on your left), until you see the Department of Sanitation on your right. At the next intersection (South Street and Montgomery Street), turn right at the light for Pier 36. (the entrance for the FDR north will be directly in front of you at the light). From New Jersey Turnpike: Proceed to Exit 14C (Holland Tunnel) Go through the Holland Tunnel and Take EXIT 5 on the left toward Canal St East. Turn slight right onto Laight St...Turn slight right onto Canal St... Turn right onto Bowery. Bowery becomes Chatham Sq. Turn left onto E Broadway...Turn right onto Samuel Dickstein Plz... Turn slight left onto Montgomery St. Turn right onto South St. and end at Pier 36, located at the intersection of South Street and Montgomery Street From the George Washington Bridge: After leaving GW Bridge, take Harlem River Drive exit, Exit 2, towards FDR Drive Proceed onto the Harlem River Drive which connects/merges into FDR Drive S. -

Western Rail Yard

Chapter 10: Neighborhood Character A. INTRODUCTION Neighborhood character is an amalgam of several elements that give an area its distinctive personality and help distinguish it from other neighborhoods. These components include: land use; street layout; scale, type, and style of development; historic features; patterns and volumes of traffic; noise levels; and any other physical or social characteristics. However, not all of these elements affect neighborhood character in all cases; a neighborhood usually draws its character from a few determining elements. Using information presented in other technical chapters of this EIS, this chapter examines neighborhood character at the three project sites and the associated surrounding study areas, and analyzes the effects of the Proposed Actions on neighborhood character in these areas. PRINCIPAL CONCLUSIONS The Proposed Actions would have a beneficial effect on neighborhood character on the project sites and in the surrounding study areas. Development of Western Rail Yard would fulfill a long- standing public policy to promote productive use of the site with a lively mix of uses, open spaces, and streets that would complement and support the development in the Hudson Yards area and West Chelsea. Construction of permanently affordable housing on the Tenth Avenue and Ninth Avenue Sites would support the Clinton neighborhood by emphasizing its residential character and the mixed-income character of its residents. DEVELOPMENT SITE The Proposed Actions would change the character of the Development Site, and this change would be, on balance, decidedly beneficial. The site, which presents a blank wall to the surrounding neighborhood on two sides and transportation/maintenance uses where it can be seen, would be transformed with a mix of residential and commercial uses and open spaces, clearly visible and accessible to the public. -

PROXY STATEMENT PURSUANT to SECTION 14(A) of the SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT of 1934 (AMENDMENT NO

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A INFORMATION (Rule 14a-101) PROXY STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 14(a) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 (AMENDMENT NO. ) Filed by the Registrant ☑ Filed by a Party other than the Registrant ☐ Check the appropriate box: ☐ Preliminary Proxy Statement ☐ Confidential, For Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) ☐ Definitive Proxy Statement ☑ Definitive Additional Materials ☐ Soliciting Material Pursuant to §240.14a-12 AMC Networks Inc. (Name of registrant as specified in its charter) (Name of person(s) filing proxy statement, if other than the registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): ☑ No fee required. ☐ Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. (1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: (5) Total fee paid: ☐ Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. ☐ Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its filing. (1) Amount Previously Paid: (2) Form, Schedule or Registration Statement No.: (3) Filing Party: (4) Date Filed: *** Exercise Your Right to Vote *** Important Notice Regarding the Availability of Proxy Materials for the Stockholder Meeting to Be Held on June 6, 2013. -

Mr. Lincoln's Tunnel

PDHonline Course C750 (4 PDH) Mr. Lincoln’s Tunnel Instructor: J.M. Syken 2014 PDH Online | PDH Center 5272 Meadow Estates Drive Fairfax, VA 22030-6658 Phone & Fax: 703-988-0088 www.PDHonline.org www.PDHcenter.com An Approved Continuing Education Provider Mr. Lincoln’s Tunnel 1 Table of Contents Slide/s Part Description 1 N/A Title 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~19 1 Midtown-Hudson Tunnel 20-50 2 Weehawken or Bust 51~89 3 The Road More Traveled 90~128 4 On the Jersey Side 129~162 5 Similar, But Different 163~178 6 Third Tube 179~200 7 Planning for the Future 2 Part 1 Midtown-Hudson Tunnel 3 Namesake 4 In 1912, there were very few good roads in the United States. The relatively few miles of improved road were around towns and cities (a road was “improved” if it was graded). That year, Carl Fisher (developer of Miami Beach and the Indianapolis Speedway, among other things) conceived a trans-continental highway. He called it the “Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway.” It would be finished in time for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition and would run from the exposition’s host city; San Francisco, to New York City. Two auto industry tycoons played major roles in the highway’s development: Frank Seiberling - president of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., and Henry Joy - president of the Packard Motor Car Company. It was Henry Joy who came up with the idea of naming the highway after POTUS Abraham Lincoln. On July 1st 1913, the Lincoln Highway Association was officially incorporated. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 9: Architectural Historic Resources ......................................................9-1 A. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................9-1 B. PRINCIPAL CONCLUSIONS ..............................................................................................9-1 C. METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................................9-2 1. OVERVIEW ..........................................................................................................................9-2 2. AREA OF POTENTIAL EFFECT (APE) ..................................................................................9-3 3. CRITERIA AND REGULATIONS ............................................................................................9-3 D. EXISTING CONDITIONS ....................................................................................................9-4 1. BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................9-4 2. DESIGNATED AND ELIGIBLE ARCHITECTURAL RESOURCES ..............................................9-5 a) Individually Designated, Listed, or Eligible Resources............................................................... 9-9 b) Garment Industry Resources.......................................................................................................9-22 c) Printing Industry Resources........................................................................................................9-32 -

2021 HCR Covered Building List

2021 HCR Covered Building List HCR ID Project Name Address City Zip 1220 Normandie Court II 1695 3 AVENUE New York 10128 1276 400 East 84th Street (The Strathmore) 1608 1 AVENUE New York 10028 1278 VillaGe East 223 EAST 6 STREET New York 10003 1360 Union Square South 842 BROADWAY New York 10003 1382 250 West 50th Street (The Gershwin) 250 WEST 50 STREET New York 10019 1394 Tribeca LandinG 400 CHAMBERS STREET New York 10282 1395 Tribeca Park 400 CHAMBERS STREET New York 10282 1404 420 Stockholm St 420 STOCKHOLM STREET Brooklyn 11237 1412 240 East 39th Street (The Paramount) 240 EAST 39 STREET New York 10016 1420 Chelsea Arms 225 8 AVENUE New York 10011 1424 345 East 94th Street (The Chesapeake) 345 EAST 94 STREET New York 10128 1426 77 West 24th St. (750 6th Ave. Chelsea VanGuard) 736 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS New York 10010 1434 Riverwatch (70 Battery Place) 70 BATTERY PLACE New York 10280 1441 1501 LexinGton (CarneGie Hill Terrace I) 1501 LEXINGTON AVENUE New York 10029 1443 Gethsemane Gardens aka Eastville Gardens 342 EAST 8 STREET New York 10009 1447 101 West End Avenue (Park Hudson) 101 WEST END AVENUE New York 10069 1450 300 East 39th Street (The Sonoma) 312 EAST 39 STREET New York 10016 1457 South Cove Plaza (50 Battery Place) 50 BATTERY PLACE New York 10280 1459 Theater Row (420 W. 42 St.) 420 WEST 42 STREET New York 10036 1460 150 East 44th Street (The Belvedere) 150 EAST 44 STREET New York 10017 1463 180 West 20th Street (The Westminister) 180 WEST 20 STREET New York 10011 1468 Webster Place Apartments 1971 WEBSTER AVENUE Bronx 10457 1471 101-117 Worth Street 111 WORTH STREET New York 10013 1475 1500 LexinGton Ave 1490 LEXINGTON AVENUE New York 10029 1477 66-68 West 38th Street (The Atlas) 66 WEST 38 STREET New York 10018 1478 269 West 47th St. -

Other Transportation Options Vip Parking General Parking Directions

Turnpike exit on the left, Merge onto I‐95 S, Take the exit onto I‐78 E Conn. & Westchester (via Tap and GSP): VIP PARKING toward Holland Tunnel, Follow signs toward 14C, Take Liberty State Park Merge onto I‐287 W/I‐87 N, Take exit 14A for Garden State Pkwy, exit, Turn right at Comunipaw Ave/Jersey City Blvd, Turn left at Phillip St, Take exit 163 on the left to merge onto N NJ‐17 toward Paramus/G Northern PA (Via I 80): Turn right at Audrey Zapp Drive, Follow signs to Lot 6 Washington Bridge/NJ‐4, Merge onto I‐80 E via the ramp on the left to I‐80 EAST, Take exit 43 to merge onto I‐287 S toward Morristown, Take New York, Take the New Jersey Turnpike/I‐95 exit toward US‐46, Merge exit 37 to merge onto NJ‐24 E toward Springfield/I‐78, Take the exit onto Newark Airport: onto I‐95 S, Take exit 15E onto Raymond Blvd US‐1/US‐9 toward Jersey I‐78 E toward New Jersey Turnpike/I‐95, Follow signs toward 14C, take Take the ramp to I‐78 E, Keep right at the fork, Follow signs for New City, Take right toward NJ‐440 S, Turn left onto Port Terminal Blvd, Follow Liberty State Park exit, Turn right at Comunipaw Ave/Jersey City Blvd, Jersey Turnpike/Holland Tunnel/I‐95/I‐78/New York City and merge onto signs into General Parking Turn left at Phillip St, Turn right at Audrey Zapp Drive, Follow signs to I‐78 E, Follow signs toward 14C, Take Liberty State Park exit, Turn right Lot 6 at Comunipaw Ave/Jersey City Blvd, Turn left at Phillip St, Turn right at Manhattan (via Holland Tunnel): Audrey Zapp Drive, Follow signs to Lot 6 Head west on I‐78 W/NJ‐139 -

Conceptual Analysis for Neighborhood Parks by Special Permit

Appendix A.3 Conceptual Analysis for Neighborhood Parks The proposed zoning text amendment analyzed in this FGEIS includes a City Planning Commission (CPC) authorization in Zoning Resolution (ZR) Section 93-23 (Height and Setback in Hell’s Kitchen (Subdistrict F) of the Special Hudson Yards District). Under the proposed Section 93-23, the CPC may authorize the distribution of floor area without regard to zoning district boundaries and height and setback modifications within C2-7A zoning districts within a portion of the proposed Special Hudson Yards District. More specifically, the authorization provisions would apply to developments or enlargements on zoning lots divided by district boundaries that are wholly or partially within a designated portion of the Hell’s Kitchen Subdistrict and provide publicly accessible open areas adjacent to or over the Lincoln Tunnel ramps. The Lincoln Tunnel ramps include the Lincoln Tunnel Expressway and Dyer Avenue, both of which are owned by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ). The directly affected area consists of the C2-7A zoning district proposed to be mapped over Subarea F1 of Subdistrict F of the Special Hudson Yards District. The proposed authorization would allow sites within this area to exceed the underlying height limit of 135 feet and reach a maximum height of 200 feet. The authorization would also allow floor area to be distributed without regard to zoning district boundaries. The directly affected area is located adjacent to properties that are proposed to be rezoned to C6-4 zoning districts as part of the Proposed Action. The increased height limit and ability to transfer floor area across zoning district boundaries allowed under the authorization is intended to facilitate the development of publicly accessible open spaces on development sites in Hell’s Kitchen. -

1 156-13-A APPLICANT – Bryan Cave LLP, for 450 West 31Street Owners Corp, Owner; OTR Media Group, Inc., Lessee. SUBJECT – Ap

156-13-A April 7, 2014, the Appellant requested withdrawal of APPLICANT – Bryan Cave LLP, for 450 West the appeal, and by letter dated April 8, 2014, DOB 31Street Owners Corp, owner; OTR Media Group, Inc., requested that the Board deny the Appellant’s request, lessee. citing concerns about public policy and its ability to SUBJECT – Application May 17, 2013 – Appeal of take enforcement actions against the Sign and other DOB determination that the subject advertising sign is similarly-situated signs; and not entitled to non-conforming use status. C6-4/HY WHEREAS, per § 1-12.2 of the Rules of Practice zoning district. and Procedure, the Board may consider a request to PREMISES AFFECTED – 450 West 31 st Street, West withdraw an appeal at any time before the Board’s final 31 st Street, between Tenth Avenue and Lincoln Tunnel determination; however, the Board may reject the Expressway, Block 728, Lot 60, Borough of Manhattan. withdrawal request if it determines that proper COMMUNITY BOARD #10M enforcement or public policy would be served by ACTION OF THE BOARD – Appeal Denied. rendering a decision; and THE VOTE TO GRANT – WHEREAS, the Board agrees with DOB that the Affirmative: .....................................................................0 appeal has broad public policy and enforcement Negative: Chair Srinivasan, Commissioner Ottley-Brown, implications; accordingly, the Appellant’s request to Commissioner Hinkson and Commissioner Montanez ...4 withdraw the appeal is denied; and Absent: Vice Chair Collins..............................................1 PROCEDURAL HISTORY THE RESOLUTION – WHEREAS, on December 22, 1999, DOB issued a WHEREAS, this is an appeal of two final permit under Job. No. 102663930; this permit authorized determinations, issued by the Manhattan Borough the installation of the structural components of the Sign Commissioner of the Department of Buildings (“DOB”) (the “Sign Structure Permit”); one day later, on on April 17, 2013 and on May 1, 2013, acting on DOB December 23, 1999, DOB issued a permit under Job.