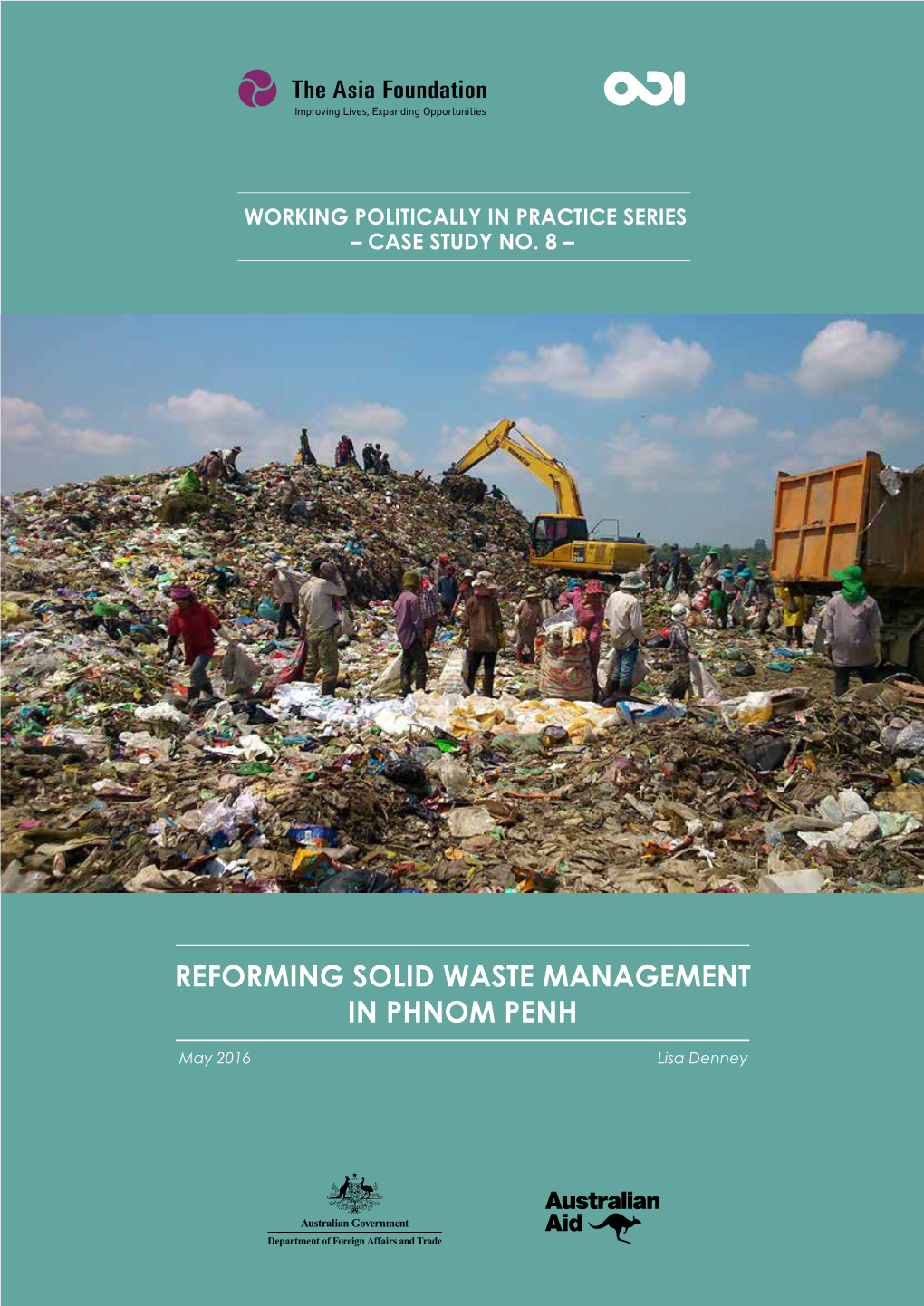

Reforming Solid Waste Management in Phnom Penh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SBI LH AR 2020(21X18cm)

CONTENT About the Bank Financial Report About the Bank Report of the Board of Directors Key Figures Report of the Independent Auditors Page Vision, Mission and Core Values Page Statement of Financial Position Corporate Lenders 1 - 28 30 - 42 Statement of Profit or Loss and Message from Chairman Other Comprehensive Income Statement of Changes in Equity Message from CEO Statement of Cash Flows Board of Directors Senior Management Organizational Chart Risk Management Branch Networks Human Resources Standard Branch Office Products and Services Page Branches 44 - 48 About the Bank About the Bank 02 Key Figures 03 Vision, Mission and Core Values 05 Corporate Lenders 06 Message from Chairman 07 Message from CEO 09 Board of Directors 11 Senior Management 15 Organizational Chart 21 Risk Management 23 Human Resources 25 Products and Services 27 01 SBI LY HOUR Bank / Annual Report 2020 ABOUT THE BANK SBI LY HOUR Bank Plc. is a joint venture between Neak Oknha LY HOUR and SBI Holdings Inc. SBI LY HOUR Bank Plc. is a company duly incorporated under the law of the Kingdom of Cambodia. The Bank’s objective is to provide in any or all commercial SBI Holdings Inc. banking business to individuals, SMEs, companies, and corporations in general as a contribution to socio-economic 70% development in Cambodia and elsewhere as conducted by all commercial banks internationally. The aim is to help Cambodia, Cambodian businesses and people to improve the living standard and grow the business by providing highly professional, technologically advanced banking services, affordable financing and bringing the latest finan- 30% cial technology to make the user’s experience easier and Neak Oknha LY HOUR more attractive. -

Visa Contactless Promotion at Lucky Group

Visa contactless promotion at Lucky Group Promotion mechanics Get USD1 cash voucher when you tap to pay with Visa contactless for a minimum spend of USD10 Promotion Period Valid from 6 August 2021 to 30 September 2021 or while stocks last Terms and conditions This promotion is eligible for all Visa Cardholders (Credit, Debit & prepaid) To Redemption voucher : Tap to pay with Visa contactless for USD10 or more in a single sale slip at any Lucky Supermarket, Lucky Premium Store, Lucky Express and The Guardian to receive voucher worth USD1 Each cardholder will limit to maximum 3 vouchers redemption per card per day The voucher(s) can be used for the next purchase with Visa contactless payment only (no minimum spend required in the next purchase) This voucher valid untill 31 October 2021 Voucher cannot be redeemed or exchange for cash Voucher redemptions are available in limited amounts, or on a first come first served basis while stocks last. Visa and DFI Lucky Private Limited reserve the rights to change, amend the terms and conditions or terminate the promotion without prior notice. DFI Lucky Private Limited’s decision on related matters related to this promotion will be final and no correspondence will be entertained. Participating merchants Lucky Supermarket Lucky Premium Lucky Express Guardian (merchant outlets in appendix) Term and condition for USD1 cash voucher to be use on next purchase The voucher can be used with payment made by Visa contactless at any outlets of Lucky Supermarket, Lucky Premium, Lucky Express and Guardian The voucher can be used upto 2 at a time The voucher can be used on or before expiry date of 31 October 2021 Voucher cannot be redeemed or exchanged for cash. -

No. Service Station Time Address 1 TOTAL Avenue De France 24 Hours Corner Street 47-61 & 84 Sangkat Sras Chak Khan Daun Penh

No. Service Station Time Address 1 TOTAL Avenue de France 24 Hours Corner Street 47-61 & 84 Sangkat Sras Chak Khan Daun Penh Phnom Penh 2 TOTAL Chateau d'Eau 05:00-20:00 Street 217+274 Sangkat Veal Vong Khan 7 Makara Phnom Penh 3 TOTAL La deesse 05:00-21:00 St. 182 & 189, Sangkat Veal Vong, Khan 7 Makara, Phnom Penh 4 TOTAL La Gare 05:00-21:00 Between Street 108 & Russian Blvd Sangkat Sras Chak Khan Daun Penh Phnom Penh 5 TOTAL Takhmao 24 Hours National Road N.2, Doem Kor Village, Khum Doem Miem, Kandal Province 6 TOTAL Monivong 24 Hours #370, Corner Street 93 & 310, Sangkat Boeung Keng Kang I, Khan Chamkamon, Phnom Penh 7 TOTAL Pochentong 05:00-22:00 Russian Blvd Phum Tek Thla Sangkat Tek Thla Khan Sen Sok Phnom Penh 8 TOTAL Marche Central (Phsa Thmey) 05:00-21:00 #602 Street Charles de Gaulle Sangkat Psar Thmei 2 Khan Daun Penh Phnom Penh 9 TOTAL Prek Leap (6A4) 05:00-22:00 Plot#126, road 6A, Phum Keanklaing, Sangkat Prek Leap, Khan Russey Keo, PP. 10 TOTAL Russey Keo 05:00-22:00 National road No5, Phum Boeng Chhouk, Sangkat Km6, Khan Russey Keo,PP. 11 TOTAL Century 24 Hours Russian Blvd, Sangkat Kakap, Khan Dankor,PP. 12 TOTAL Odem 05:00-22:00 NR4, Odem Village, Sangkat Chaom Chao, Khan Porsenchey, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. 13 TOTAL Toul Kok 05:00-22:00 St.289,Sangkat Boeung Kak II, Khan Toul Kok, Phnom Penh , Cambodia. 14 TOTAL Phnom Penh Thmey 05:00-22:00 St.1986 Sangkat Phnom Penh Thmey, Khan Sen Sok, Phnom Penh 15 TOTAL Chroy Changva 05:00-20:00 Phum 3, Sangkat Chroy Changvar, Khan Chroy Changvar , Phnom Penh City 16 TOTAL Chbar Ampov 24 Hours National road No1, Sangkat Chbar Ampov I, Khan Chbar Ampov, Phnom Penh. -

CBRE-Cambodia-Map.Pdf

St. 598 St. 273 St. 337 St. Samdach Penn Nouth (289) (289) Nouth Nouth Penn Penn Samdach Samdach St. St. St. 315 St. 315 St. 598 St. 598 P hn o m P en h Ha St. 592 no i F r i en National Highway 5 St. 315 d s h i p B l v d . (1 01 9) St. 273 d (110) ration de la Russie Blv St. 337 Street 200R édé Conf National Highway 6 Street 99 MaoTse Toung Blvd (245) St. Samdach Penn Nouth (289) (289) Nouth Nouth Penn Penn Samdach Samdach St. St. National Highway 5 5 Highway Highway National National Oknha Mong Reththy St. (1928) St. 598 Oknha Try Heng Try St.(2011)Oknha St. 315 St. Monivong Blvd (93) St. 273 Mekong River Street St. 337 Street 2011 St. Samdach Penn Nouth (289) (289) Nouth Nouth Penn Penn Samdach Samdach St. St. Tonle Sap Street Preah SIsowath Quay St. 315 Oknha Tep Phan St. (182) St. 598 Wat Phnom St. 592 St. 315 Street 105K Y Y o o Central Market t t h h Confédération de la Russie Blvd (110) 9ǒǻ>6h4¡Z a a p p Preah Monivong Blvd (93) 110) ssie Blvd ( o o Kampuchea Krom Blvd (128) Ru ration de la fédé Con l l St. 215 St. Sisowath K K MaoTse Toung Blvd (245) h St. 315 h Norodom Blvd e ASEAN 11 e Royal Palace Oknha Tep Phan St. (182) m m Y Y o o t t h h a a p p a a o o l l Independence Monument K K h h e e r r m m a a a a r r a a k k P P k h k o Olympic Stadium Preah Sihanouk Blvd (274) u m B P P Olympic Northbridge St.(1019) l v Market d ( 2 7 Street 2004 1 h ) St. -

Is Divided Into 24 “Sections” (ខណ្ណkhan, Also

Divisions administratives de la municipalité de Phnom Penh et codes postaux – Mise à jour Administrative divisions of the Municipality of Phnom Penh and ZIP Codes - Update Remarque : Pour la version initialement publiée de ce document, nous avions pris comme source la page de la Poste Cambodgienne donnant les codes postaux des différents quartiers de la ville de Phnom Penh. Un lecteur de Khmerologie nous a fait remarquer que la liste que nous donnions n’était pas à jour. Effectivement, vérification, nous nous sommes aperçus que le site de la Poste Cambodgienne n’avait pas pris en compte la réorganisation des arrondissements et quartiers de Phnom Penh qui a été faite en 2019. Pour rédiger la présente version mise à jour, nous nous sommes appuyés sur la base de données du site du NCDD (National Committee for Sub-National Democratic Development), organisme du gouvernement cambodgien. Note: For the initial version of this document, we used the webpage of Cambodia Post that gives the ZIP codes of all sangkats of the city of Phnom Penh. However, a reader of Khmerologie let a message stating that our document was not up to date. After verification, we have discovered that the website of Cambodia Post does not take into account the reorganization of the administrative divisions of Phnom Penh that occurred in 2019. For the updated version of this document, we used the database published on the website of the NCDD (National Committee for Sub-National Democratic Development), which is part of the Royal Government of Cambodia. Le Royaume du Cambodge est divisé administrativement en « 25 provinces et capitale ». -

Ministry of Commerce ្រពឹត ិប្រតផ ូវក រ សបា ហ៍ទី ៣០-៣៥ ៃនឆា

䮚ពះ楒ᾶ㮶ច䮚កកម�ុᾶ ᾶតិ 絒ស侶 䮚ពះម腒ក䮟䮚ត KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA NATION RELIGION KING 䮚កសួង奒ណិជ�កម� 侶យក⥒�នកម�សិទ�ិប�� MINISTRY OF COMMERCE Department of Intellectual Property 䮚ពឹត�ិប䮚តផ�ូវŒរ OFFICIAL GAZETTE ស厶� ហ៍ទី ៣០-៣៥ ៃន᮶�ំ ២០២១ Week 30-35 of 2021 03/September/2021 (PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY) ែផ�កទី ១ PP AA RR TT II ការចុះប��ីថ�ី NNEEWW RREEGGIISSTTRRAATTIIOONN FFRROOMM RREEGG.. NNoo.. 8844228855 ttoo 8844887766 PPaaggee 11 ttoo 119977 ___________________________________ 1- េលខ⥒ក់奒ក䮙 (APPLICATION No. ) 2- Œលបរ ិេច�ទ⥒ក់奒ក䮙 (DATE FILED) 3- 掶� ស 掶៉់ ក (NAME OF APPLICANT) 4- 襒សយ⥒�ន掶�ស់掶៉ក (ADDRESS OF APPLICANT) 5- 䮚បេទស (COUNTRY) 6- េ⅒�ះ徶�ក់ᅒរ (NAME OF AGENT) 7- 襒សយ⥒�ន徶�ក់ᅒរ (ADDRESS OF AGENT) 8- េលខចុះប��ី (REGISTRATION No) 9- Œលបរិេច�ទចុះប��ី (DATE REGISTERED) 10- គំរ ូ掶៉ក (SPECIMEN OF MARK) 11- ជពូកំ (CLASS) 12- Œលបរ ិេច�ទផុតកំណត់ (EXPIRY DATE) ែផ�កទី ២ PP AA RR TT IIII RREENNEEWWAALL PPaaggee 119988 ttoo 226633 ___________________________________ 1- េលខ⥒ក់奒ក䮙េដម (ORIGINAL APPLICATION NO .) 2- Œលបរ ិេច�ទ⥒ក់奒ក䮙េដម (ORIGINAL DATE FILED) 3- (NAME OF APPLICANT) 掶� ស 掶៉់ ក 4- 襒 ស យ ⥒� ន 掶� ស 掶៉់ ក (ADDRESS OF APPLICANT) 5- 䮚បេទស (COUNTRY) 6- េ⅒�ះ徶�ក់ᅒរ (NAME OF AGENT) 7- 襒សយ⥒�ន徶�ក់ᅒរ (ADDRESS OF AGENT) 8- េលខចុះប��េដ ី ម (ORIGINAL REGISTRATION No) 9- Œលបរ ិេច�ទចុះប��ីេដម ORIGINAL REGISTRATION DATE 10- គ ំរ 掶៉ ូ ក (SPECIMEN OF MARK) 11- ំ (CLASS) ជពូក 12- Œលបរ ិេច�ទ⥒ក់奒ក䮙សំ◌ុចុះប��ី絒ᾶថ� ី (RENEWAL FILING DATE) 13- Œលបរ ិេច�ទចុះប��ី絒ᾶថ� ី (RENEWAL REGISTRATION DATE) 14- Œលបរ ិេច�ទផុតកំណត់ (EXPIRY DATE) ែផ�កទី ៣ PP AA RR TT IIIIII CHANGE, ASSIGNMENT, MERGER -

Assessment of Public–Private Partnership in Municipal Solid Waste Management in Phnom Penh, Cambodia

sustainability Article Assessment of Public–Private Partnership in Municipal Solid Waste Management in Phnom Penh, Cambodia Vin Spoann 1,* , Takeshi Fujiwara 2, Bandith Seng 2, Chanthy Lay 3 and Mongtoeun Yim 4 1 Department of Economic Development, Royal University of Phnom Penh, Russian Federation Blvd, Toul Kork, Phnom Penh 855, Cambodia 2 Graduate School of Environmental and Life Science, Okayama University, 3-1-1 Tsushima-Naka, Kita-ku, Okayama 700-8530, Japan; [email protected] (T.F.); [email protected] (B.S.) 3 Research Office, Royal University of Phnom Penh, Russian Federation Blvd, Toul Kork, Phnom Penh 12156, Cambodia; [email protected] 4 Department of Environmental Science, Royal University of Phnom Penh, Russian Federation Blvd, Toul Kork, Phnom Penh 12156, Cambodia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 January 2019; Accepted: 19 February 2019; Published: 26 February 2019 Abstract: The overall responsibility for waste management in Phnom Penh Capital (PPC) has rested with the municipal authorities and contracted waste collection companies. Providing waste collection services is a major challenge for Phnom Penh due to the increasing waste volume and the deficiency of the system under public–private partnership. In response to continuing population growth and urbanization, sustainable management is necessary. This study reviewed the details of the processes and examined the performance of the private sector and local government authorities (LGAs). The study used sustainability assessment, according to a success and efficiency factor method. This assessment method was developed to support solid waste management in developing countries. Multiple sustainability domains were evaluated: institutional, legislative, technical, environmental and health aspects as well as social, economic, financial and critical aspects. -

CPB-Annualreport-2014-ENG.Pdf

CORPORATE MISSION [[ 1 [ . [ . CONTENTS 1 CORPORATE MISSION 4 CORPORATE INFORMATION 6 BRANCH NETWORK 14 CORPORATE PROFILE 15 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 16 SIMPLIFIED BALANCE SHEET 17 SUMMARY OF THREE-YEAR GROWTH 18 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2 20 BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ PROFILE 26 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 31 POLICY AND PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 37 BUSINESS OPERATION TARGET 40 ANALYSIS OF THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 42 REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 48 REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT AUDITORS TO THE SHAREHOLDERS 50 CONSOLIDATED BALANCE SHEET 51 CONSOLIDATED INCOME STATEMENT 52 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 53 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS 54 SEPARATE BALANCE SHEET 55 SEPARATE INCOME STATEMENT 56 SEPARATE STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 57 SEPARATE STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS 58 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 131 CALENDAR OF SIGNIFICANT EVENTS 2014 3 CORPORATE INFORMATION Tan Sri Dato’ Sri Dr. Teh Hong Piow Tan Sri Datuk Seri Utama Thong Yaw Hong Mr. Phan Ying Tong Dato’ Sri Lee Kong Lam 4 Dr. Ghanty Sam Abdoullah Mr. Quah Poh Keat Dato’ Chang Kat Kiam !" Dato’ Chia Lee Kee Mr. Ong Ming Teck # KPMG Cambodia Ltd. 4th Floor, Delano Centre No. 144, Street No. 169 Sangkat Veal Vong Khan 7 Makara Phnom Penh Kingdom of Cambodia $% Campu Bank Building No. 23, Kramuon Sar Avenue (Street No. 114) Sangkat Phsar Thmey 2 Khan Daun Penh Phnom Penh Kingdom of Cambodia Telephone : (855) 23 222 880 / 222 881 / 222 882 Fax : (855) 23 222 887 SWIFT : CPBLKHPP E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.campubank.com.kh 5 BRANCH NETWORK BRANCHES IN PHNOM PENH & Ground & 1st Floor, Campu Bank Building No. -

Ministry of Commerce ្រពឹត ិប្រតផ ូវក រ សបា ហ៍ទី ២៧-២៩

䮚ពះ楒ᾶ㮶ច䮚កកម�ុᾶ ᾶតិ 絒ស侶 䮚ពះម腒ក䮟䮚ត KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA NATION RELIGION KING 䮚កសួង奒ណិជ�កម� 侶យក⥒�នកម�សិទ�ិប�� MINISTRY OF COMMERCE Department of Intellectual Property 䮚ពឹត�ិប䮚តផ�ូវŒរ OFFICIAL GAZETTE ស厶� ហ៍ទី ២៧-២៩ ៃន᮶�ំ ២០២១ Week 27-29 of 2021 23/July/2021 (PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY) ែផ�កទី ១ PP AA RR TT II ការចុះប��ីថ�ី NNEEWW RREEGGIISSTTRRAATTIIOONN FFRROOMM RREEGG.. NNoo.. 8833880033 ttoo 8844228844 PPaaggee 11 ttoo 116611 ___________________________________ 1- េលខ⥒ក់奒ក䮙 (APPLICATION No. ) 2- Œលបរ ិេច�ទ⥒ក់奒ក䮙 (DATE FILED) 3- 掶� ស 掶៉់ ក (NAME OF APPLICANT) 4- 襒សយ⥒�ន掶�ស់掶៉ក (ADDRESS OF APPLICANT) 5- 䮚បេទស (COUNTRY) 6- េ⅒�ះ徶�ក់ᅒរ (NAME OF AGENT) 7- 襒សយ⥒�ន徶�ក់ᅒរ (ADDRESS OF AGENT) 8- េលខចុះប��ី (REGISTRATION No) 9- Œលបរិេច�ទចុះប��ី (DATE REGISTERED) 10- គំរ ូ掶៉ក (SPECIMEN OF MARK) 11- ជពូកំ (CLASS) 12- Œលបរ ិេច�ទផុតកំណត់ (EXPIRY DATE) ែផ�កទី ២ PP AA RR TT IIII RREENNEEWWAALL PPaaggee 116622 ttoo 225511 ___________________________________ 1- េលខ⥒ក់奒ក䮙េដម (ORIGINAL APPLICATION NO .) 2- Œលបរ ិេច�ទ⥒ក់奒ក䮙េដម (ORIGINAL DATE FILED) 3- (NAME OF APPLICANT) 掶� ស 掶៉់ ក 4- 襒 ស យ ⥒� ន 掶� ស 掶៉់ ក (ADDRESS OF APPLICANT) 5- 䮚បេទស (COUNTRY) 6- េ⅒�ះ徶�ក់ᅒរ (NAME OF AGENT) 7- 襒សយ⥒�ន徶�ក់ᅒរ (ADDRESS OF AGENT) 8- េលខចុះប��េដ ី ម (ORIGINAL REGISTRATION No) 9- Œលបរ ិេច�ទចុះប��ីេដម ORIGINAL REGISTRATION DATE 10- គ ំរ 掶៉ ូ ក (SPECIMEN OF MARK) 11- ំ (CLASS) ជពូក 12- Œលបរ ិេច�ទ⥒ក់奒ក䮙សំ◌ុចុះប��ី絒ᾶថ� ី (RENEWAL FILING DATE) 13- Œលបរ ិេច�ទចុះប��ី絒ᾶថ� ី (RENEWAL REGISTRATION DATE) 14- Œលបរ ិេច�ទផុតកំណត់ (EXPIRY DATE) ែផ�កទី ៣ PP AA RR TT IIIIII CHANGE, ASSIGNMENT, MERGER -

Full List of Approved Sending Organization (Cambodia)

FULL LIST OF APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION (CAMBODIA) Person in charge of Training Contact Point in Japan Approved date No. Name of Organization Address URL (the date of Name of person in Name of TEL Email Name Address TEL Email receipt) charge of training Representative #5D-6D, Russian Federation blvd., Prey Tea Village, Sangkat Mr. DUCH [email protected] Mr. KATAYAMA 1029-7 Motoyoshida-cyo, Mito-city, [email protected] 1 168Manpower Supply CO., LTD. N/A 092 222 807 N/A 080 31736884 2018/1/16 Chaom Chao, Khan Porsenchey, Phnom Penh, Cambodia SOTHEARITH om TSUKASA Ibaraki-ken, Japan Zip310-0836 m #174, Str 21BTZ, Sangkat Beongtompoun, Khan Meanchey, Mrs. UNG SEANG Chiba-Ken, Chiba-Sai, Midori-Cho, 2 57 Goal Manpower CO., LTD. N/A 015 365 777 [email protected] Mr. USAMI HIROSHI N/A 81 90 5808 4757 [email protected] 2018/1/16 Phnom Penh, Cambodia RITHY 1731-8 A.P.T.S.E & C (Cambodia) Resources #169E0, Str 3, Sombour Meas Village, Sangkat Dong Khor, Mr. KANEKO 22Chi Nogurocho Toyohashi-shi Aichi 3 N/A Mr. SIM THO 093 833 473 N/A N/A 81 532 26 5806 [email protected] 2018/1/16 CO., LTD. Khan Dong Khor, Phnom Penh, Cambodia MASAYOSHI 441-8022 Japan AGRI- FARMARS (CAMBODIA) CO., #18, Str 384, Sangkat Toul Svay Prey 2, Khan Chamkamon, 3085-1 Yogita Town, Zentsuji City, farmers.as- 4 N/A Mr. LUY SOTHY 023 213 321 [email protected] Mr. TOCH CHENDA N/A 090 664 710 13 2018/1/16 LTD. -

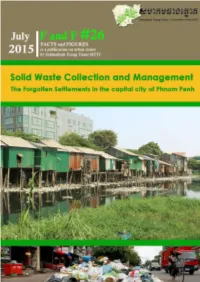

Here 60% of Interviewees Do Not Benefit from These Necessary Services

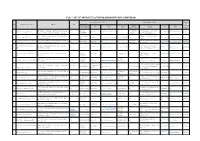

SOLID WASTE COLLECTION AND MANAGEMENT THE FORGOTTEN SETTLEMENTS IN THE CAPITAL CITY OF PHNOM PENH Printed Date: July 2015 Published by: Sahmakum Teang Tnaut Research Team: Nhim Kim Eang, Research Coordinator, Bour Chhayya, Senior Research Officer, Pom Seila, Research Officer Research Consultant: Sok Serey Map Produced by: Tim Sreyleak, Senior Mapping Officer Supported by grants from Misereor, Sida, Diakonia, Human Rights Based Spatial Planning Project, European Union, People in Need Sahmakum Teang Tnaut, July 2015 www.teangtnaut.org Table of Contents Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................... I List of tables....................................................................................................................................... I List of figures ..................................................................................................................................... I Key messages for practitioners, planners and policy makers ............................................................ 1 Chapter I ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter II ......................................................................................................................................... -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name : LENG MAREDY Address : #54E1, Street 369, Sang Kat Chbar Ampov1 , Khan Chbar Ampov, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Tel : (855) 61810090 Email : [email protected] PERSONAL INFORMATION: Family Name : Leng Given Name : Maredy Sex : Female Nationality : Cambodian Date of Birth : 25th January 2000 Place of Birth : Phnom Penh Marital Status : Single EDUACATION: [2017-present] : Studying Tourism of Management, year 4 student at Royal University of Phnom Penh [2014-2017] : Graduated English level 12 at ASEAN International School [2014-2017] :Graduated from Chbar Ampov High school [2006-2012] :Studied grade 1-6 Chbar Ampov Primary School LANGUAGES: Khmer : Native language English : Fluent in speaking, reading, writing and listening EXPERIENCE: 2016 : Teaching student at home (Tutor) 2017 : Debate on Speaking 2018 : Selling book at Book fair and Package Tour 2019 : Working on project Clean and Green with UNDP and Coca Cola ( Core Team) 2019-Present : Working in hotel as Receptionist at Aquarius Hotel & Urban Resort SKILL: - Computer Knowledge: MS Word, Excel, and Power Point - Communication - Work as a team and individual INTERESETS: - Communicate with people - Reading book - Learning and sharing - Explore new places - Sports ( Swimming , taekwondo) REFERENCE: Name : Ms. Hun Chansocheata Position : English Instructor at Stanford American School Tel : 070678790 E-mail : [email protected] Leng Maredy #54E1, St. 369, Chbar ampov1, Khan Chbar ampov, Phnom Penh, Cambodia (855) 61810090 Dear Sir/Madam, As you have announced recently in seeking for Customer service on the website, I am absolutely enthusiastic in applying for this position. With my experience and skills, I believe that I am an appropriate candidate for this position.