Hopkins and Uranian Problematics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iovino, Serenella. "Bodies of Naples: a Journey in the Landscapes of Porosity." Ecocriticism and Italy: Ecology, Resistance, and Liberation

Iovino, Serenella. "Bodies of Naples: A Journey in the Landscapes of Porosity." Ecocriticism and Italy: Ecology, Resistance, and Liberation. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 13–46. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219488.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 17:51 UTC. Copyright © Serenella Iovino 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 Bodies of Naples A Journey in the Landscapes of Porosity In the heart of the city of Naples there is a place with a curious name: Largo Corpo di Napoli. This little square opens up like an oyster at a point where the decumani, the Greek main streets, become a tangle of narrow medieval lanes and heavy gray-and-white buildings. Like an oyster, this square has a pearl: An ancient statue of the Nile, popularly known as Corpo di Napoli, the body of Naples. The story of this statue is peculiar. Dating back to the second or third centuries, when it was erected to mark the presence of an Egyptian colony in the city, the statue disappeared for a long time and was rediscovered in the twelfth century. Its head was missing, and the presence of children lying at its breasts led people to believe that it represented Parthenope, the virgin nymph to whom the foundation of the city is mythically attributed. In 1657 the statue was restored, and a more suitable male head made it clear that the reclining figure symbolized the Egyptian river and the children personifications of its tributaries. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

Some Uranian Astrology History

Beginners Guide to Uranian Astrology by Anna Sanchez a free product of My Astro World Like us on Facebook Follow us on youtube The Rules Poem (penned by Ludwig Rudolph from the Rulebook) Don't take the rules too literally and think, they are so valid for me. Their systematic stimulation should give rise to inspiration, furnish possibilities. Help in applying capabilities for a correct interpretation. You have passed the limitations if, by experience and thought, to the right spot you have brought, each configuration. Avoid interpretations of sorrow with this astrology of tomorrow. Buy Rules For Planetary Pictures by Alfred Witte & Ludwig Rudolph Some Uranian Astrology History Alfred Witte hypothesized that beyond Neptune there would be bodies that could fill in gaps of astrology at the time and by symmetry in the sky explain certain events with consistency. He then began to assign names and values to what he hypothesized as their meaning. He began with Pluto. It is in fact the first of his Trans-Neptunes and he did so as an astronomer and an actual professional surveyor from the ground using the same principles of surveying the land on the sky to arrive at his hypothesis. He was in fact correct and his development of the astrology and the work proved to be much more accurate than anything astrology had seen. Alfred Witte hypothesized about the existence of a celestial body being just beyond Neptune and called it Pluto before a telescope confirmed it’s actual existence. Since astrology had long been co-opted and controlled by cliques and cult like groups it was difficult to get any other groups or people to assist. -

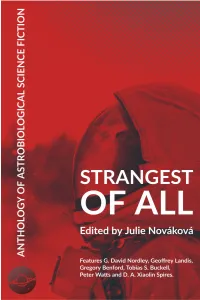

Strangest of All

Strangest of All 1 Strangest of All TRANGEST OF LL AnthologyS of astrobiological science A fiction ed. Julie Nov!"o ! Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute Features G. %avid Nordley& Geoffrey Landis& Gregory 'enford& Tobias S. 'uc"ell& (eter Watts and %. A. *iaolin S#ires. + Strangest of All , Strangest of All Edited originally for the #ur#oses of 'EACON +.+.& a/conference of the Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute 0EA$1. -o#yright 0-- 'Y-N--N% 4..1 +.+. Julie No !"o ! 2ou are free to share this 5or" as a 5hole as long as you gi e the ap#ro#riate credit to its creators. 6o5ever& you are #rohibited fro7 using it for co77ercial #ur#oses or sharing any 7odified or deri ed ersions of it. 8ore about this #articular license at creati eco77ons.org9licenses9by3nc3nd94.0/legalcode. While this 5or" as a 5hole is under the -reati eCo77ons Attribution3 NonCo77ercial3No%eri ati es 4.0 $nternational license, note that all authors retain usual co#yright for the indi idual wor"s. :$ntroduction; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :)ar& $ce& Egg& =ni erse; < +..+ by G. %a id Nordley :$nto The 'lue Abyss; < 1>>> by Geoffrey A. Landis :'ac"scatter; < +.1, by Gregory 'enford :A Jar of Good5ill; < +.1. by Tobias S. 'uc"ell :The $sland; < +..> by (eter )atts :SET$ for (rofit; < +..? by Gregory 'enford :'ut& Still& $ S7ile; < +.1> by %. A. Xiaolin S#ires :After5ord; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :8artian Fe er; < +.1> by Julie No !"o ! 4 Strangest of All :@this strangest of all things that ever ca7e to earth fro7 outer space 7ust ha e fallen 5hile $ 5as sitting there, isible to 7e had $ only loo"ed u# as it #assed.; A H. -

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs

Hubert Kennedy Karl Heinrich Ulrichs Pioneer of the Modern Gay Movement Peremptory Publications San Francisco 2002 © 2002 by Hubert Kennedy Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, Pioneer of the Modern Gay Movement is a Peremtory Publica- tions eBook. It may be freely distributed, but no changes may be made in it. An eBook may be cited the same as a printed book. Comments and suggestions are welcome. Please write to [email protected]. 2 3 When posterity will one day have included the persecution of Urnings in that sad chapter of other persecutions for religious belief and race—and that this day will come is beyond all doubt—then will the name of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs be constantly remembered as one of the first and noblest of those who have striven with courage and strength in this field to help truth and charity gain their rightful place. Magnus Hirschfeld, Foreword to Forschungen über das Rätsel der mannmännlichen Liebe (1898) Magnus Hirschfeld 4 Contents Preface 6 1. Childhood: 1825–1844 12 2. Student and Jurist: 1844–1854 18 3. Literary and Political Interests: 1855–1862 37 4. Origins of the “Third Sex” Theory: 1862 59 5. Researches on the Riddle of “Man-Manly” Love: 1863–1865 67 6. Political Activity and Prison: 1866–1867 105 7. The Sixth Congress of German Jurists, More “Researches”: 1867–1868 128 8. Public Reaction, The Zastrow Case: 1868–1869 157 9. Efforts for Legal Reform: 1869 177 10. The First Homosexual Magazine: 1870 206 11. Final Efforts for the Urning Cause: 1871–1879 217 12. Last Years in Italy: 1880–1895 249 13. -

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825-1895) Was Probably “The First Man in the World to Come Out.”

Wouldn’t You Like to Be Uranian? Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (1825-1895) was probably “the First man in the world to come out.” Uranian -- 19th Century term used by Karl Heinrich Ulrichs in 1864. BeFore this, “homosexuality” was known only as a behavior—sodomy— not a constitutional quality oF personality. Ulrichs developed a more complex threeFold axis For understanding sexual and gender variance: sexual orientation (male-attracted, bisexual, or Female-attracted), preferred sexual behavior (passive, no preference, or active), and gender characteristics (Feminine, intermediate, or masculine). The three axes were usually, but not necessarily, linked — Ulrichs himselF, For example, was a Weibling (Feminine homosexual) who preFerred the active sexual role. Ulrichs called homosexuals: Urnings (German) or Uranians. Uranus was the most recently discovered planet in 1781. Like Mars to males and Venus to Females, Uranus was to homosexuals. Reference to Uranus the planet is that this is something newly discovered even though it has always been there. Uranian came originally From Greek myth and Plato’s Symposium. Uranus was the god of the heavens and was said to be the Father oF Aphrodite in “a birth in which the Female had no part .” i.e, the distinction between male and Female is unimportant. In those early days, the German Sexologists, including Magnus Hirschfeld (1868- 1935), thought homosexuals were Female souls trapped/reincarnated in male bodies. Homosexual was coined by Karl-Maria Kertbeny (1824-1882) in 1869 in an anonymous pamphlet about Prussian sodomy laws. Kertbeny was a travel writer and journalist who wrote about human rights. When he was a young man, a gay Friend killed himselF because oF extortion. -

REPRESENTATION of the ANCIENT MYTH ABOUT HYPERION in MODERN GRAPHIC LITERATURE Evelina Luchko Postgraduate Student, Oles Honcha

SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL OF POLONIA UNIVERSITY 44 (2021) 1 REPRESENTATION OF THE ANCIENT MYTH ABOUT HYPERION IN MODERN GRAPHIC LITERATURE Evelina Luchko Postgraduate Student, Oles Honchar Dnipro National University, Ukraine e-mail: [email protected], orcid.org/0000-0002-0979-9723 Summary The article aims to investigate the peculiarities of the new myth about Hyperion embod- ied in Marvel’s periodical graphic literature in comparison with the tradition of literary inter- pretations of the traditional Titanomachy myth. The article considers graphic literature to be a developing intermedial genre gaining popularity among readers, although underestimated by scholars. The interconnections between the comics and romantic and postmodern literature are studied. It is also highlighted that borrowings from European literature are a characteristic feature of American cultural tradition due to the lack of its own ancient basis. The article also traces the influence of modern comic tradition on reconsidering the ancient story about a rebel- lious titan. Functioning of superheroes as role models for the youth, the tendency for comic authors to depict conventional characters being close to modern realia and understandable for mass readers comes into the focus of the research. Thus, a new myth about Hyperion of the XXI century is created, in which the main character becomes a combination of such iconic images as Prometheus and Superman, reconsidered in the way making it possible for the image to serve the agenda and ideology. Keywords: comics, new myth, titan, Marcus Milton, Avengers, Marvel, mass reader DOI: https://doi.org/10.23856/4409 1. Introduction Comics, or graphic novels, are a relatively new genre of art, although its roots go deep into prehistoric times. -

C 2008 Laura A. Diehl ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

c 2008 Laura A. Diehl ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ESTRANGING SCIENCE, FICTIONALIZING BODIES: VIRAL INVASIONS, INFECTIOUS FICTIONS, AND THE BIOLOGICAL DISCOURSES OF “THE HUMAN,” 1818-2005 by LAURA ANNE DIEHL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program of Literatures in English Written under the direction of Harriet Davidson And approved by _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ _____________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Estranging Science, Fictionalizing Bodies: Viral Invasions, Infectious Fictions, and the Biological Discourses of “the Human,” 1818-2005 LAURA ANNE DIEHL Dissertation Director: Harriet Davidson In 1818, Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein causes science and literature—two different discourses, two different signifying systems, two different realities—to collide. As it addresses the givenness, or “naturalness,” of “the human,” Frankenstein reimagines the putative boundary between the human and the nonhuman, a fictive border made perceptible by contemporary scientific investigation. Catalyzing a new genre, science fiction, Shelley estranges the enlightenment discourse of “reason,” revealing it as a highly regulative structure through which societies are forged and bodies governed. “Estranging Science, Fictionalizing Bodies: Viral Invasion, Infectious Fictions, and the Biological Discourses of ‘the Human,’ 1818-2005, posits a mutually infective relationship between science and literature. It both exposes the logic of purification that delimits “modern” forms of knowledge as discursively distinct (science v. literature) and considers how this distinction informs the evolutionary/philosophical shifts in how we think about the possible, the human, and the novel. -

— Conclusion — 'The Daring of Poets Later Born': the Uranian Continuum, 1858-2005

— Conclusion — ‘The Daring of Poets Later Born’: The Uranian Continuum, 1858-2005 ‘Because Beneath the Lake a Treasure Sank’: Johnson’s Shaping of Ionica and Dolben Boy, go convey this purse to Pedringano; Thou knowest the prison; closely give it him. [….] Thou with his pardon shalt attend him still. Show him this box; tell him his pardon’s in’t. But open’t not, […] if thou lovest thy life. (Lorenzo to his pageboy, The Spanish Tragedy )1 William Johnson ( later Cory), who was educated at Eton and King’s College, Cambridge, 2 returned to Eton in 1845 as a Classics master, and taught there until he was dismissed in 1872 for exercising a paederastic pedagogy that Timothy d’Arch Smith describes as a ‘brand of passive inversion’. 3 While at Eton, Johnson had an ‘ability to pick out apt and sympathetic pupils’, which, although praised educationally, created ‘a less palatable, deeper-seated reputation of a 1 Thomas Kyd (attributed), The Spanish Tragedy , in Katharine Eisaman Maus, ed., Four Revenge Tragedies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), III, iv, lines 61-73. 2 At King’s College, Cambridge, Johnson was a celebrated student, gaining the Chancellor’s English Medal for a poem titled Plato in 1843, and the Craven Scholarship in 1844. He was appointed to an assistant mastership at Eton upon graduating from Cambridge. See William Johnson ( later Cory), Ionica [Parts I and II], by William Cory, with biographical intro. and notes by Arthur C. Benson (London: George Allen, 1905), p.xii. All of Johnson’s poems are taken from this volume; abbreviated as Ionica 1905. -

(Eonmmxial Ifcaher

MENIT-ED f t / i Drivers with cigarettes or cigars in their mouths can be as dangerous as drunks. Now that spring is here and autoists drive with open windowjs the danger is compounded. Driving in congested traffic takes all of the attention — and both hands. Smokers who can (Eonmmxial Ifcaher be blinded by a wind-blown ash or who give up TEN CENTS Per Copy control of their cars to flick their cigarettes are a SIid SOUTH-BERGEN REVIEW danger to themselves and everybody else around. There ought to be a law. Second-Class postage paid at Rutherford, N .J. Vol. 51, No. 36 Thursday, April 6, 1972 Published at 251 Ridge Rd.. Lyndhurst Subscription $3.00 66% Satisfied W ith G overnm ent Form Sixty six percent of In announcing the results -yndhurst residents feel the Charles N. Wormke, spokesman present government is adequate for the Jaycees, declared: I Com m ents On Survey | and 69 percent would buy Forty terse, tart comments on conditions in Lyndhurst Homes again in Lyndhurst. “According to John Stuart were made public today by the Jaycees, the organization that These were salient features Mill, “ In tim es of crisis we recently completed a survey in the township. Most of the of a feedback received by the must avoid both ignorant comments were similar to feelings expressed by tenants about change and ignorant opposition Lyndhurst Jaycees in response their landlords. While the survey showed the majority are to change.” According to to questionnaires sent out to satisfied with the form of government the comments indicated 4 ,000 homes. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

Uranian Astrology for Beginners

Beginners Guide to Uranian Astrology by Anna Sanchez a free product of My Astro World Like us on Facebook Follow us on youtube The Rules Poem (penned by Ludwig Rudolph from the Rulebook) Don't take the rules too literally and think, they are so valid for me. Their systematic stimulation should give rise to inspiration, furnish possibilities. Help in applying capabilities for a correct interpretation. You have passed the limitations if, by experience and thought, to the right spot you have brought, each configuration. Avoid interpretations of sorrow with this astrology of tomorrow. Buy Rules For Planetary Pictures by Alfred Witte & Ludwig Rudolph Uranian Astrology For Beginners 1.) We read a chart by examining all of the midpoints on every planet axis point in our chart. The compilation of the midpoints on every axis point is “the story” of that planet or midpoint question. 2.) We ask the chart a question by finding the corresponding formula for the question and then reviewing all the midpoints, points and planets on that axis point. This is how we read and analyze every single thing in Uranian Astrology. We will always be the sum of all of our parts in life. We are also always the sum of all of our planets, points and axis points in good astrology. Axis point analysis is how we read everything in Uranian Astrology. An axis point tells the story of any question we have pose to the chart by way of midpoint. The Math Symbols. The slash (/) as the indicator of a half sum or midpoint.