Karl Heinrich Ulrichs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gewinner Weihnachtsverlosung 2020 / 2021

Gewinner Weihnachtsverlosung 2020 / 2021 Nr. Preis Spender Gewinner Name PLZ + Wohnort 1 750 € Reisegutschein Werbegemeinschaft L. Niersmann 31600 Uchte 2 Fernseher (43 Zoll) inkl. Aufstellen Werbegemeinschaft Buchholz 31600 Uchte 3 150 € Reifengutschein Werbegemeinschaft Beate Döhrmann 31604 Raddestorf 4 Große Weinflasche Montrose Werbegemeinschaft Ursula Kelkenberg 31592 Stolzenau 5 100 € Gutschein WEZ Werbegemeinschaft Willi Gäbe 31600 Uchte 6 Gutschein Kaltes Buffet 80,- Schlachter Schumacher Nicole Büsching 31592 Stolzenau 7 Hartschalen-Trolly Werbegemeinschaft Torsten Garrelts 31600 Uchte 8 125 € Gutschein Schneider Werbegemeinschaft Björn Radtke 27245 Bahrenborstel 9 Dolce Gusto Kaffemaschine Werbegemeinschaft Tobias Lohstroh 31606 Warmsen 10 50 € Gutschein WEZ Werbegemeinschaft Neele Steinbeck 31600 Uchte 11 50 € Gutschein WEZ Werbegemeinschaft Florian Schildmeier 31600 Uchte 12 50 € Gutschein WEZ Werbegemeinschaft Neele Steinbeck 31600 Uchte 13 50 € Gutschein WEZ Werbegemeinschaft Gerd Falldorf 31600 Uchte 14 50 € Gutschein WEZ Werbegemeinschaft Jule-Marit Meyer 31600 Uchte 15 50 € Gutschein WEZ Werbegemeinschaft Heinz Meier 31600 Uchte 16 Crepe-Maker Werbegemeinschaft Daniela Nachsel Cloppenburg 17 Gutschein 50 € Magro Anna Barg 31600 Uchte 18 Nike - Cappy Schuhhaus Niemeyer Louis Schildmeier 31600 Uchte 19 Digitalwaage Werbegemeinschaft Erika Meyer 31592 Stolzenau 20 Kissenset Werbegemeinschaft Seligmann 31600 Uchte 21 50 € Gutschein Sehzentrum Lübber Werbegemeinschaft M. Eichberger 31600 Uchte 22 50 € Gutschein Sehzentrum -

Das Alte Sempacherlied B

The Ancient Song of Sempach Of bold forefathers in days of old Let their heroic feats be told Of the lance striking home and the clash of swords dire, Of battle dust and the vapor of blood on fire! Our sacred song we dedicate to Winkelried; He is our hero. For us he did bleed. “Look after my wife and child so dear, To you I entrust them without fear!” Calling out to his men before the foe, Strong Struthan grabbed the long spear and forced it low, Burying it in his powerful chest was his decree, To die with God in his heart for the right to be free. And over the body blessed His heroic comrades swiftly pressed On home terrain Swiss swords like lightning fell The murderous horde to quell; And freedom’s victory all hail In all ages hence from mountain to dale. The German lyrics of “The Ancient Song of Sempach” and the following excerpt have been translated by Norman Barry from: Dr. Hans Rudolf Fuhrer’s excellent article “Arnold Winkelried – der Held von Sempach 1386” in PALLASCH, Zeitschrift für Miltärgeschichte [= The Magazine for Military History, published in Salzburg, Austria] (Organ der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Mlitärgeschichte), No. 23, Autumn 2006, p. 71. Was there an historic Arnold von Winkelried? One year later Peter F. Kopp noted that The ground-breaking dissertation by Beat today’s critically-minded historians are Suter entitled “Arnold von Winkelried, the Hero unanimously of the opinion that neither the of Sempach,” completed in 1977, explicitly heroic feat nor a Winkelried can be ascribed to brackets this question out. -

NATIONAL IDENTITY in SCOTTISH and SWISS CHILDRENIS and YDUNG Pedplets BODKS: a CDMPARATIVE STUDY

NATIONAL IDENTITY IN SCOTTISH AND SWISS CHILDRENIS AND YDUNG PEDPLEtS BODKS: A CDMPARATIVE STUDY by Christine Soldan Raid Submitted for the degree of Ph. D* University of Edinburgh July 1985 CP FOR OeOeRo i. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART0N[ paos Preface iv Declaration vi Abstract vii 1, Introduction 1 2, The Overall View 31 3, The Oral Heritage 61 4* The Literary Tradition 90 PARTTW0 S. Comparison of selected pairs of books from as near 1870 and 1970 as proved possible 120 A* Everyday Life S*R, Crock ttp Clan Kellyp Smithp Elder & Cc, (London, 1: 96), 442 pages Oohanna Spyrip Heidi (Gothat 1881 & 1883)9 edition usadq Haidis Lehr- und Wanderjahre and Heidi kann brauchan, was as gelernt hatq ill, Tomi. Ungerar# , Buchklubg Ex Libris (ZOrichp 1980)9 255 and 185 pages Mollie Hunterv A Sound of Chariatst Hamish Hamilton (Londong 197ý), 242 pages Fritz Brunner, Feliy, ill, Klaus Brunnerv Grall Fi7soli (ZGricýt=970). 175 pages Back Summaries 174 Translations into English of passages quoted 182 Notes for SA 189 B. Fantasy 192 George MacDonaldgat týe Back of the North Wind (Londant 1871)t ill* Arthur Hughesp Octopus Books Ltd. (Londong 1979)t 292 pages Onkel Augusta Geschichtenbuch. chosen and adited by Otto von Grayerzf with six pictures by the authorg Verlag von A. Vogel (Winterthurt 1922)p 371 pages ii* page Alison Fel 1# The Grey Dancer, Collins (Londong 1981)q 89 pages Franz Hohlerg Tschipog ill* by Arthur Loosli (Darmstadt und Neuwaid, 1978)9 edition used Fischer Taschenbuchverlagg (Frankfurt a M99 1981)p 142 pages Book Summaries 247 Translations into English of passages quoted 255 Notes for 58 266 " Historical Fiction 271 RA. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Rundbrief Nr. 47

Erster Vorsitzender: Dr. Albert Groeneveld, Zeisigweg 25, 48683 AHAUS Tel.: 02561-43478 Email: [email protected] Sekretariat: Günther Groeneveld ·Reformierter Kirchgang 17 ·26789 LEER Tel.: 0491-9796995 · Fax: 0491-9768953 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.diegroenevelds.de 47. Rundbrief Ahaus, November 2009 Liebe Verwandte, liebe Freunde der Familie Groeneveld! Auch in diesem Jahr möchten wir zum Jahresende über interessante Ereignisse der Familie Groeneveld berichten. Erfreulicherweise haben die Verbindungen in die USA durch den Familientag einen großen Schub bekommen. Im Sommer haben Anke und Hinrich Groeneveld aus dem bayrischen Moosburg unsere Verwandten in den USA besucht. Einen anschaulichen Bericht über diese Reise können Sie in diesem Rundbrief lesen. Wiederum einen Deutschlandbesuch gönnten sich Reverend Dr. John David Muyskens und seine Frau Donna, geb. Greenfield (Nr. 2372 IX) aus Grand Rapids in Michigan (USA). Initiator der Europareise war ihr Sohn Mark, der seinen drei Kindern John, Carolyn und Joel die familiären Wurzeln zeigen wollte. Deshalb führte sie die Reise nicht nur nach Ostfriesland, sondern auch auf die westfriesische Insel Terschelling, wo die Vorfahren der Familie Muyskens einst lebten. Auf der holländischen Insel konnten sie sogar in dem Haus wohnen, das früher ihren Vorfahren gehörte. Von dort ging die Reise mit Fähre, Zug und Mietauto ins Emsland nach Lingen zu Anna (Nr. 2406) und Gerhard Schultz. Zum Abschluss besuchten sie die Familie von Dr. Ulrike (Nr. D 136) und Dr. Manfred Hinrichs in Warsingsfehn. Beide führen dort die Arztpraxis ihres Vaters, unseres Ehrenvorsitzenden Dr. Heinrich Groeneveld (Nr. D 101), fort. Der Vorstand des Familienverbandes hat auch über ein neues Familienfest diskutiert. -

Ticino-Milano Dal 15.12.2019 Erstfeld Ambrì- Orario Dei Collegamenti Milano Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona

Hier wurde der Lago Maggiore 4 mm nach links verschoben Hier wurde der Lago Maggiore 4 mm nach links verschoben Luzern / Zürich Luzern /Lu Züzernrich / Zürich Luzern /Lu Zürizercnh /Lu Züzernrich / Zürich Luzern /Lu Zzüernrich /Lu Zürizercnh / Zürich Luzern /Lu Züzernrich / Zürich Luzern /Lu Züzrernich / Zürich Luzern /Lu Zürizercnh / Zürich Luzern /Lu Zzüriercnh / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Luzern /Erst Zürichfeld Luzern / ZürichErstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Erstfeld Orario dei collegamentiOrario deiMilano collegamentiOrario Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona.Orario dei collegamenti deiMilano collegamentiOrario Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. deiMilano collegamenti Milano Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona.Orario Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. deiMilano collegamenti Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona.Orario Milanodei collegamentiOrario Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. dei collegamentiOrario Milano dei Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. collegamenti Milano Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. Milano Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. Erstfeld Luzern / Zürich Luzern / Zürich Erstfeld Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Ambrì- Orario dei collegamenti Ticino-Milano dal 15.12.2019 Erstfeld Ambrì- Orario dei collegamenti Milano Centrale–Lugano–Bellinzona. GöschenenErstfeld Piotta Faido LaGöschenenvorgo PiottaGöschenenFaido LaGöschenenvorgo Piotta FaidoPiottaLaGöschenenvorgFoaido Lavorgo Piotta Faido LaGöschenenvorgo Piotta Faido LaGöschenenvorgo PiottaGöschenenFaido Lavorgo PiottaGöschenenFaido -

Ticino on the Move

Tales from Switzerland's Sunny South Ticino on theMuch has changed move since 1882, when the first railway tunnel was cut through the Gotthard and the Ceneri line began operating. Mendrisio’sTHE LIGHT Processions OF TRADITION are a moving experience. CrystalsTREASURE in the AMIDST Bedretto THE Valley. ROCKS ChestnutsA PRICKLY are AMBASSADOR a fruit for all seasons. EasyRide: Travel with ultimate freedom. Just check in and go. New on SBB Mobile. Further information at sbb.ch/en/easyride. EDITORIAL 3 A lakeside view: Angelo Trotta at the Monte Bar, overlooking Lugano. WHAT'S NEW Dear reader, A unifying path. Sopraceneri and So oceneri: The stories you will read as you look through this magazine are scented with the air of Ticino. we o en hear playful things They include portraits of men and women who have strong ties with the local area in the about this north-south di- truest sense: a collective and cultural asset to be safeguarded and protected. Ticino boasts vide. From this year, Ticino a local rural alpine tradition that is kept alive thanks to the hard work of numerous young will be unified by the Via del people. Today, our mountain pastures, dairies, wineries and chestnut woods have also been Ceneri themed path. restored to life thanks to tourism. 200 years old but The stories of Lara, Carlo and Doris give off a scent of local produce: of hay, fresh not feeling it. milk, cheese and roast chestnuts, one of the great symbols of Ticino. This odour was also Vincenzo Vela was born dear to the writer Plinio Martini, the author of Il fondo del sacco, who used these words to 200 years ago. -

Urning: Representing Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and His Legacy Through the Mechanism of Theatre

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2019-06 Urning: Representing Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and His Legacy through the Mechanism of Theatre Diller, Ryan Diller, R. (2019). Urning: Representing Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and His Legacy through the Mechanism of Theatre (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110571 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Urning: Representing Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and His Legacy through the Mechanism of Theatre by Ryan Diller A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DRAMA CALGARY, ALBERTA JUNE, 2019 © Ryan Diller 2019 UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES The undersigned certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance, a thesis entitled “Urning: Representing Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and His Legacy through the Mechanism of Theatre” submitted by Ryan Diller in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Fine Arts. ____________________________________________________________ Supervisor, Professor Clement Martini, Department of Drama ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Patrick James Finn, Examination Committee Member, Department of Drama ____________________________________________________________ Dr. -

Mobil Und Dabei Sein Samtgemeinde Uchte 1 Ämter Rathaus, Samtgemeindebüro Balkenkamp 2 31600 Uchte

mobil und dabei sein Samtgemeinde Uchte Ämter Rathaus, Samtgemeindebüro Eingangsbereich Balkenkamp 2 Haupteingang 31600 Uchte Flügeltür n. innen B 92 cm Tel: 05763 / 1830 Podest: 200 x 200 x 17 cm Fax: 05763 / 18381 9 Stufen H 17 cm E-mail: [email protected] Handlauf re. u. li. H 75 cm website: www.samtgemeinde-uchte.de Klingel für Rollstuhlfahrerinnen / Rollstuhlfahrer H 120 cm, Gegensprechanlage Gemeindeverwaltung Eingangsbereich Außenstelle Diepenau Haupteingang Am Bahnhof Doppelflügeltür n. außen B 90 cm 31603 Diepenau 2 Stufen H 20 cm OT Lavelsloh Rampe 9 %, L 700 cm Tel: 05775 / 1442 Klingel H 115 cm, Gegensprechanlage Windfang: T 220 cm Gemeindeverwaltung Eingangsbereich Außenstelle Warmsen Haupteingang Am Bahnhof 4 Doppelflügeltür n. außen B 100 cm 31606 Warmsen ebenerdig Tel: 05767 / 941488 Windfang: T 150 cm Fax: 05767 / 94 1487 Gemeindeverwaltung Eingangsbereich Außenstelle Raddestorf Haupteingang 1 mobil und dabei sein Samtgemeinde Uchte Raddestorf 36 Flügeltür n. außen B 104 cm 31604 Raddestorf Podest: 220 x 200 x 14 cm Tel: 05765 / 725 Behinderten –WC Behinderten-WC Eingangsbereich Marktplatz / Busbahnhof Haupteingang 31600 Uchte ebenerdig Volkshochschule Volkshochschule Uchte Arbeitsstellenleiter: Kursorte und deren Dr. Juliane Petrich- Bauer Gegebenheiten erfragen. Darlaten Nr. 23 31600 Uchte Tel: 05763 / 3151 Fax: 05763 / 3151 Fahrdienste Taxi Bohm Bahnhofstraße 26 31603 Diepenau Tel: 05775 / 234 2 mobil und dabei sein Samtgemeinde Uchte Taxi Osterkamp Mindener Straße 3 31600 Uchte Rollstuhlbeförderung Tel: 05763 / 2526 Freizeit Büchereien Gemeindebücherei Eingangsbereich Zur Sparkasse 2 Haupteingang ist der rückw. Eingang der 31600 Uchte Sparkasse: Tel: 05763 / 182504 Flügeltür n. außen B 101 cm Steigung 5 % Flureingang: Flügeltür n. außen B 105 cm Büchereieingang: Flügeltür n. -

Bildung & Teilhabe in Stolzenau

V Das Steuerungsteam Ann Fischer - Jugendhaus WipIn Stolzenau Ute Müller - Haus der Generationen Stolzenau Kerstin Pieper - Landkreis Nienburg/Weser Heidrun Reinhardt - KiTa Pusteblume Stolzenau Nadine Schlier - Rathaus Landesbergen Carmen Wieczorek - Rathaus Landesbergen V Kontakt Bildung & Teilhabe Rathaus Landesbergen in Carmen Wieczorek Hinter den Höfen 13 31628 Landesbergen Stolzenau Telefon: +49 5761 - 705 222 [email protected] www.sg-mittelweser.de V Wer oder was ist V Wie arbeiten wir? BuTiS? Aktuelle Bedarfe und Handlungsfelder werden gemeinsam ermittelt. Dabei ist uns wichtig, nicht nur die Sicht der Fachkräfte zu berücksichtigen, sondern die verschiedenen Blickwinkel und Potenziale Die Initiative Bildung und Teilhabe in Stolze- der Beteiligten mit einzubeziehen und umzusetzen. Basis für den Erfolg der Initiative sind die Ver- nau engagiert sich dafür, die Teilhabe und netzung aller Beteiligten und die Transparenz der Angebote. Bildungschancen für Kinder, Jugendliche und junge Familien mit und ohne Migrationshinter- grund zu verbessern. V Wo sind wir aktiv? Das Steuerungsteam setzt sich aus verschie- denen Organisationen zusammen. Wir analy- • „Toleranz im Topf“ ist ein halbjährlich stattfindendes, interkulturelles Koch-Angebot. sieren die aktuelle Situation vor Ort und pas- sen unsere Arbeit exakt den tatsächlichen • Kurdischer Müttertreff im WipIn. Bedarfen an. • Eltern-Cafès: KiTa Pusteblume, Kinderhaus Rasselbande und Regenbogenschule. V Was sind unsere Ziele? • Interkulturelle Gesprächskreise im Haus der Generationen. Wir verbessern die Bildungschancen von Kin- • Tanzgruppe für alle Kinder in der Pusteblume. dern, Jugendlichen und jungen Familien. Wir • Hausaufgaben- und Bewerbungshilfe im WipIn. wollen die gesellschaftliche Teilhabe aller hier lebenden Familien sowie die Qualität und Viel- • Migrationsarbeit, Hausaufgabenhilfe und Lernförderung im Haus der Generationen. falt der Bildungslandschaft vor Ort weiter ent- wickeln und fördern. -

Gemeinsame Bekanntmachung Der Städte Bassum, Diepholz, Sulingen

Gemeinsame Bekanntmachung der Städte Bassum, Diepholz, Sulingen, Syke und Twistringen der Gemeinden Stuhr, Wagenfeld und Weyhe sowie der Samtgemeinden "Altes Amt Lemförde", Barnstorf, Bruchhausen- Vilsen, Kirchdorf, Rehden, Schwaförden und Siedenburg gem. §§ 42 Abs. 3 und § 50 Abs. 5 Bundesmeldegesetz (BMG) über das Widerspruchsrecht gegen die Weitergabe bestimmter Daten. Bundesmeldegesetz vom 3. Mai 2013 (BGBl. I S. 1084), das durch Artikel 8 des Gesetzes vom 04. August 2019 (BGBl. I S. 1131) geändert worden ist, räumt den Meldepflichtigen die Möglichkeit ein, in bestimmten Fällen der Übermittlung von Daten ohne Angabe von Gründen zu widersprechen (§§ 42 Abs. 3 und 50 Abs. 5 BMG). Dabei handelt es sich um Datenübermittlungen an 1. öffentlich-rechtliche Religionsgesellschaften über Familienangehörige, die nicht derselben oder keiner öffentlich-rechtlichen Religionsgesellschaft angehören (im Falle des Widerspruchs darf nur die Mitteilung erfolgen, daß der Ehegatte einer anderen oder keiner öffentlich-rechtlichen Religionsgesellschaft angehört), 2. Träger von Wahlvorschlägen (z. B. Parteien, Wählergruppen) im Zusammenhang mit allgemeinen Wahlen, 3. Presse und Rundfunk sowie Mitglieder parlamentarischer und kommunaler Vertretungskörper- schaften über Alters- und Ehejubiläen und 4. Adressbuchverlage. In diesem Zusammenhang wird ausdrücklich auf die Möglichkeit hingewiesen, dass die von der Meldebehörde übermittelten und durch Adressbuchverlage abgedruckten Daten durch Dritte zur Herstellung elektronischer Verzeichnisse genutzt werden könnten, sodass vielfältige Auswertungs- möglichkeiten gegeben wären. Des Weiteren können betroffene Personen gem. § 58 c Abs. 1 S. 1 Soldatengesetz i.V.m. § 36 Abs. 2 BMG über das Widerspruchsrecht der Datenübermittlung von Personen an das Bundesamt für Personalmanagement der Bundeswehr Gebrauch machen. Meldepflichtige, die von dem Widerspruchsrecht Gebrauch machen wollen, müssen dies ihrer jeweils zuständigen Meldebehörde schriftlich mitteilen. -

Download.Php?Id=422 E136d4ac (PDF-Dokument)

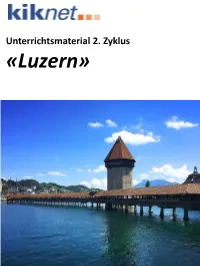

Unterrichtsmaterial 2. Zyklus «Luzern» Luzern 2. Zyklus Lektionsplan Nr. Thema Worum geht es?/Ziele Inhalt und Action Sozialform Material Zeit AB «Die Form des Kreativität fördern anhand mitgebrachter Zeitungen/Zeitschriften Vierwaldstättersees» Gedächtnis anregen, eigene Lernwege zur 1 Icebreaker die Umrisse des Vierwaldstättersees in einer EA/GA Zeitungen/Zeitschriften 20` Erinnerung an die Form des Reisscollage darstellen Leimstifte Vierwaldstättersees zulassen A3-Papier wichtige Kennzahlen und Fakten zum Kanton SuS suchen die verlangten Informationen rund AB «Facts and Figures» und der Stadt finden und kennen um Luzern aus dem Internet zusammen. Lösungen «Facts and Figures» 2 Facts and Figures EA 30` evtl. Vergleich mit dem Selbstständige Korrektur anhand eines PC oder Tablet mit Heimatkanton/Heimatort Lösungsblattes. Internetzugang Erarbeiten und Vertiefen des Wissens über den Tourismus in Luzern und in der Schweiz AB «Gäste aus der Ferne» SuS stellen Mutmassungen über den Tourismus allgemein AB «Deutsch für Luzern-Touristen» Gäste aus der in Luzern an und bringen ihr Vorwissen ein. 3 Fremdsprachenkenntnisse erweitern und GA/Plenum Wörterbücher 45` Ferne SuS erstellen ein eigenes Wörterbuch mit den vertiefen evtl. Zugang zu Online- wichtigsten Begriffen für Touristen in Luzern. Vorwissen in verschiedenen Sprachen Wörterbüchern einbringen AB «Geschichte des Kantons SuS recherchieren selbstständig zu Geschichte des einen Überblick über unterschiedliche