Sources of the Cape Khoekhoe and Kora Records Vocabularies, Language Data and Texts

Total Page:16

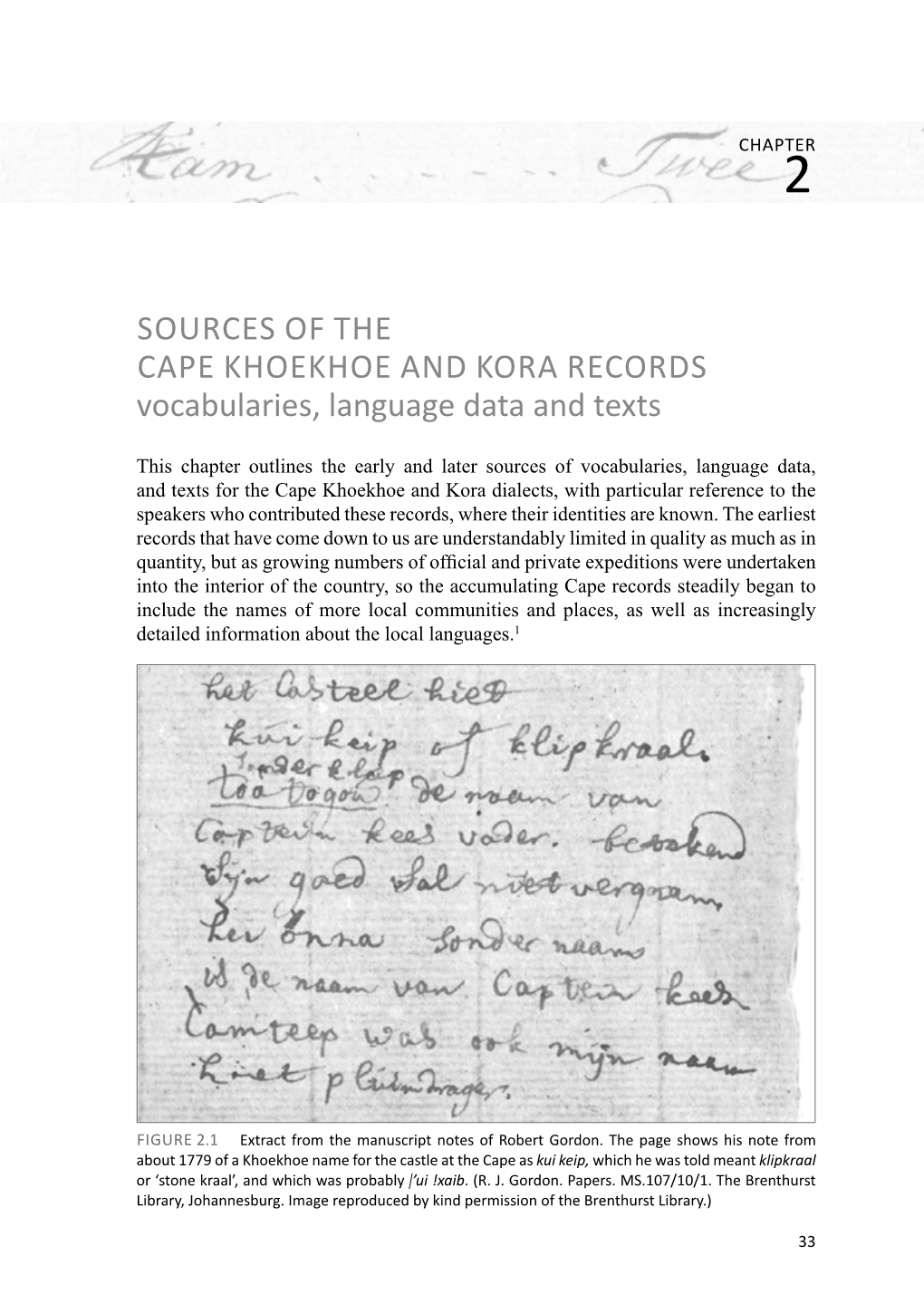

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

Understanding and Dealing with Ancestral Practices in Botswana

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 1997 Understanding and Dealing With Ancestral Practices in Botswana Stanley P. Chikwekwe Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Chikwekwe, Stanley P., "Understanding and Dealing With Ancestral Practices in Botswana" (1997). Dissertation Projects DMin. 32. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/32 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the co p y submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

An Analysis of the Construction of Tswana Cultural Identity in Selected Tswana Literary Texts

AN ANALYSIS OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF TSWANA CULTURAL IDENTITY IN SELECTED TSWANA LITERARY TEXTS GABAITSIWE ELIZABETH PILANE BA, BA (Hons), MA, PTC Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Tswana at the Potchefstroomse Universiteit vir Christelike Hoer Onderwys. Promoter : Prof H. M. Viljoen Co-promoter : Dr. R. S. Pretorius Potchefstroom 2002 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my promoter Professor H. M. Viljoen who guided me through the years that I was busy with my thesis. He has been so patient in advising and encouraging me. From him I learnt hard work and perseverance. He was always ready to help and give a word of encouragement and for this, I thank him very much. My gratitude goes to my co-promoter Dr. R. S. Pretorius for his valuable guidance and advice throughout the process of completing this thesis. Colloquial thanks to my husband Bogatsu and my children for their sacrifice, and encouragement, as well as their support and love during my study and my absence from home. A word of gratitude to my son Phiri Joseph Pilane for typing the thesis. Finally I would like to thank God for protecting me through this study and giving me the strength and patience to bring the research to completion. Ill DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to the memory of my late parents-in-law, Ramonaka Pilane and Setobana Stella Pilane, who passed away before they could enjoy the fruits of their daughter-in-law's studies. IV DECLARATION I declare that this thesis for the degree of Philosophiae Doctor at the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education, hereby submitted by me, has not previously been submitted by me for a degree at this University and that all sources referred to have been acknowledged. -

The African E-Journals Project Has Digitized Full Text of Articles of Eleven Social Science and Humanities Journals

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies vol.17 (2003) nO.1 European Missionaries and Tswana Identity in the 19th Century Stephen Vo/z University ofWisconson-Madison, USA email: [email protected] Abstract During the nineteenth century, 'Batswana' became used as label for a large number of people inhabiting the interior of southern Africa, and European missionaries played an important role in the evolution of the term's meaning and the adoption of that meaning by both Europeans and Batswana. Through their long years of residence among Batswana and development ofwrillenforms of Sets wan a, missionaries became acknowledged by other Europeans as experts on Tswana culture, and their notions of Tswana ethnicity became incorporated into European understandings of Africans and, eventually, into Batswana understandings of themselves. The development of Tswana identity passed through several stages and involved different layers of construction, depending on the level of European knowledge of Tswana societies, the purposes served by that knowledge, and the changing circumstances of Tswana peoples' relations with Europeans and others. Although Tswana identity has, in a sense, been invented, that identity has not existed in one set form nor has it simply been imposed upon Africans by Europeans. Parallel to European allempts to define Tswana- ness, Batswana developed their own understandings of Tswana identity, and although missionaries contributed much to the formation of 'Tswana' identity, it was not purely a European invention but resulted instead from interaction between Europeans and Africans and their mutual classification of the other in reference to themselves. -

Apartheid South Africa

Apartheid South Africa 1948-1994 APARTHEID IN SOUTH AFRICA To understand the events that led to the creation of an independent South Africa. To understand the policy of apartheid and its impact. To understand what caused the end of apartheid and the challenges that remain. Colonization: Settling in another country & taking it over politically and economically. Cultures Clash The Dutch were the first The Europeans who settled Europeans to settle in in South Africa called South Africa. themselves Afrikaners. They set up a trade Eventually, the British took station near the Cape of control of most of South Good Hope. Africa. Cultures Clash The British and the The British eventually Afrikaners (also known as defeated the Afrikaners the Boers) fought each and Zulus and declared other for control of South Africa an South Africa. independent country in The British also fought 1910. with the Zulu tribe. The Birth of Apartheid They created a system called The white-controlled APARTHEID, which was designed government of South to separate South African Africa created laws to society into groups based on keep land and wealth in race: whites, blacks, the hands of whites. Coloureds, and Asians. What is Apartheid? System of racial segregation in South Africa. Lasted from 1948-1994 Created to keep economical and political power with people of English descent/heritage National Party (1948) In 1948, the National Party came to power in South Africa. Promoted Afrikaner, or Dutch South African, nationalism. Instituted a strict racial segregation policy called apartheid. In 1961, South Africa was granted total independence from Great Britain. -

Who Are the Ndebele and the Kalanga in Zimbabwe?

Who are the Ndebele and the Kalanga in Zimbabwe? Gerald Chikozho Mazarire Paper Prepared for Konrad Adenuer Foundation Project on ‘Ethnicity in Zimbabwe’ November 2003 Introduction Our understanding of Kalanga and Ndebele identity is tainted by a general legacy of high school textbooks that have confessedly had a tremendous impact on our somewhat obviated knowledge of local ethnicities through a process known in history as ‘feedback’. Under this process printed or published materials find their way back into oral traditions to emerge as common sense historical facts. In reality these common sense views come to shape both history and identity both in the sense of what it is as well as what it ought to be. As the introduction by Terence Ranger demonstrates; this goes together with the calculated construction of identities by the colonial state, which was preoccupied with naming and containing its subjects (itself a legacy on its own). Far from complicating our analysis, these legacies make it all the more interesting for the Ndebele and Kalanga who both provide excellent case studies in identity construction and its imagination. There is also a dimension of academic research, which as Ranger observes, did not focus on ethnicity per-se. This shouldn’t be a hindrance in studying ethnicity though; for we now know a lot more about the Ndebele than we would have some 30years ago (Beach 1973). In contrast, until fairly recently, we did not know as much about the Kalanga who have constantly been treated as a sub-ethnicity of the major groups in southwestern Zimbabwe such as the Ndebele, Tswana and Shona. -

Anthropological Myths, Racial Archives and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Pigments of Our Imagination: Anthropological Myths, Racial Archives and the Transnationalism of Apartheid A dissertation in partial satisfaction of the requirements of the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Kirk Bryan Sides 2014 © Copyright by Kirk Bryan Sides 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Pigments of Our Imagination: Anthropological Myths, Racial Archives and the Transnationalism of Apartheid by Kirk Bryan Sides Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Jennifer Sharpe, Chair “Pigments of Our Imagination: Anthropological Myths, Racial Archives and the Transnationalism of Apartheid” repositions South African cultural production within discourses on Africa, the Black Atlantic, and the Indian Ocean. By focusing on apartheid’s intellectual origins, this project begins by mapping the production of a transnational race discourse between Germany and South Africa in order to situate apartheid within a broader circulation of ideas on race and colonial governmentality. I argue that this transnational dialogue embodies a larger shift in the racial technologies utilized by nation-states over the course of the twentieth century, in which the employment of anthropology gained increasing significance in the development of national race policies. Exploring the ways in which pre-apartheid intellectuals articulated a ‘new language’ for representing race to the state, I demonstrate that as apartheid ideology coalesced it ii did so under an increasingly cartographical rubric for imagining how races were to be organized within South Africa. As a form of colonial racial governance, I show how apartheid’s geographical mapping of race was also ideologically buttressed by a historical imperative of projecting ideas of racial difference and distinction back into the southern African past. -

South Africa's People

Pocket Guide to South Africa 2011/12 SOUTH AFRICA’S PEOPLE SOUTH AFRICA’S PEOPLE 9 Pocket Guide to South Africa 2011/12 SOUTH AFRICA’S PEOPLE People South Africa’s biggest asset is its people; a rainbow nation with rich and diverse cultures. South Africa is often called the cradle of humankind, for this is where archaeologists discovered 2,5-million-year-old fossils of our earliest ancestors, as well as 100 000-year-old remains of modern man. According to Statistics South Africa’s (Stats SA) Mid-Year Population Estimates, 2011, released in July 2011, there were 50,59 million people living in South Africa, of whom 79,5% were African, 9% coloured, 2,5% Indian and 9% white. Approximately 52% of the population was female. Nearly one third (31,3%) of the population was aged younger than 15 years and approximately 7,7% (3,9 million) was 60 years or older. Of those younger than 15 years, approximately 23% (3,66 million) lived in KwaZulu-Natal and 19,4% (3,07 million) lived in Gauteng. The South African population consists of the Nguni (comprising the Zulu, Xhosa, Ndebele and Swazi people); Sotho-Tswana, who include the Southern, Northern and Western Sotho (Tswana people); Tsonga; Venda; Afrikaners; English; coloured people; Indian people; and those who have immigrated to South Africa from the rest of Africa, Europe and Asia and who maintain a strong cultural identity. Members of the Khoi and the San also live in South Africa. Languages According to the Constitution of South Africa, 1996, everyone has the right to use the language and participate in the cultural life of their choice, but no one may do so in a manner that is inconsistent with any provision of the Bill of Rights. -

BOPHUTHATSWANA" C/O Professor F

NOT I::OR PUBLICATION WITHOUT WRITER'S CONSENT KB-5 INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS BOPHUTHATSWANA" c/o Professor F. de Villiers A' 'Bi'a'ck Sate 0r 't'ate of Mind'?' School of Law, UNIBO P/Bag X2046 nabatho, Bophuthatswana May 18, 1982 Mr. Peter Bird Martin Executive Director Institute of Current World Affairs Wheelock House West Wheelock Street Hanover, New Hampshire 03755 USA Dear Peter, Bophuthatswana is a unique --live in Bophuthatswana and $. Africs. place in southern Africa. It is Over sixty percent of Bophuthat- considered by South Africa to be swana's citizens still live and an independent black state, but work in South Africa, mostly in it consists of seven completely townships outside of Pretoria. separate pieces of land. It has Looking at the dispersal accepted independence but it of the Tswana; in Botswana which lies entirely within South Afri- was the largest traditionally ca's borders. It has a bill of Tswana region, there are the fewest rights which South Africa does number of people. The next larg- not, and has declared apartheid est area, Bophuthatswana, has the and discrimination on the basis next largest number of people. of race, creed or color illegal. Then, near Pretoria, in mostly However, it is making conscious impoverished "township" communit- efforts to have the cultural ies are the vast majority of make-up of the country be mostly T swana pe o ple. blaeks of Tswana descent. So, we are presented with Bophuthatswana is the re- a landlocked "country" broken sult of South Africa's attempts into numerous unconnected pieces. -

South Africa, De Voortrekkers and Come See the Bioscope Ilha Do Desterro: a Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, Núm

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Saks, Lucia A Tale of Two Nations: South Africa, De Voortrekkers and Come See the Bioscope Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 61, julio-diciembre, 2011, pp. 137-187 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348699006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-8026.2011n61p137 A TALE of Two Nations: South Africa, DE VOORTREKKERS AND COME SEE THE BIOSCOPE Lucia Saks University of Cape Town/University of Michigan Abstract: This paper examines two films, De Vootrekkers (1916) and Come See the Bioscope (1997), made at two moments of national crisis in South African history, the first at the beginning and the second at the end of the twentieth century. Both films speak to the historical moment of their production and offer very different visions of the nation and the necessity for reconciliation. Keywords: cinema, South Africa, national identity, post apartheid, reconciliation. (M)y knowledge of movies, pictures, or the idea of movie-making, was strongly linked to the identity of a nation. That’s why there is no French television, or Italian, or Brit- ish, or American television. -

Homelands,” and “Black States”: Visual Onomastic Constructions of Bantustans in Apartheid South Africa

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 18, Issue 4| October 2019 Beyond Seeing QwaQwa, “Homelands,” and “Black States”: Visual Onomastic Constructions of Bantustans in Apartheid South Africa OLIVER NYAMBI and RODWELL MAKOMBE Abstract: The Bantustans – separate territories created for black African occupation by the apartheid regime in South Africa were some of the most telling sites and symbols of “domestic colonialism” in South Africa. In them resided and still reside the overt and covert influences, beliefs and knowledge systems that defined and characterised the philosophy and praxis of “separate development” or apartheid as a racial, colonial, socio-political and economic system. The Bantustan exhibits many socio-economic and political realities and complexes traceable to apartheid’s defining tenets, philosophies and methods of constructing and sustaining racialized power. Names of (and in) the Bantustan are a curious case. No study has systematically explored the onomastic Bantustan, with a view to understanding how names associated with it reflect deeper processes, attitudes, instabilities and contradictions that informed apartheid separate development philosophy and praxis. This article enters the discourse on the colonial and postcolonial significance of the Bantustan from the vantage point of Bantustan cultures, specifically naming and visuality. Of major concern is how names and labels used in reference to the Bantustan frame and refract images of black physical place and spaces in ways that reflect the racial constructedness of power and the spatio- temporality of identities in processes of becoming and being a Bantustan. The article contextually analyzes the politics and aesthetics of purposefully selected names and labels ascribed to black places by the apartheid regime as part of a strategic restructuring of both the physical and political landscapes. -

On Meinhof¶S Law in Bantu Nancy C. Kula 1. Introduction Phono

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Essex Research Repository /LFHQVLQJVDWXUDWLRQDQGFRRFFXUUHQFHUHVWULFWLRQVLQVWUXFWXUHRQ0HLQKRI¶V /DZLQ%DQWX Nancy C. Kula ,QWURGXFWLRQ Phonological co-occurrence restrictions as seen in Bantu Meinhof’s Law raise interesting questions for the nature of phonological domains and in particular, what restrictions apply in the definition of such phonological domains. Government Phonology is one framework that has gone some way in defining the boundaries of phonological domains by utilising the notion of licensing. A phonological domain thus has the formal definition under the licensing principle of Kaye [29] given in (1). (1) /LFHQVLQJ3ULQFLSOH: all positions within a phonological domain are licensed save one, the head. This paper will focus on Meinhof’s Law (ML) which has been described both as a voicing dissimilation (Meinhof [40]) and (nasal) assimilation (Herbert [21], Katamba 1 and Hyman [28]) process. It is akin in nature to Japanese 5HQGDNX (Itô and Mester [25]) where the initial consonant in the second element of a compound is voiced, but this voicing is barred if another voiced segment is already present in the phonological domain. Whereas there is no restriction on the adjacency of the segments involved in 5HQGDNX some notion of adjacency is called for in ML where only obstruents in a sequence of nasal+consonant clusters (henceforth NC’s or NC clusters) are affected by the rule.2 In its most general form, ML can be characterised as a process that disallows a sequence of two voiced obstruents within NC clusters, i.e.