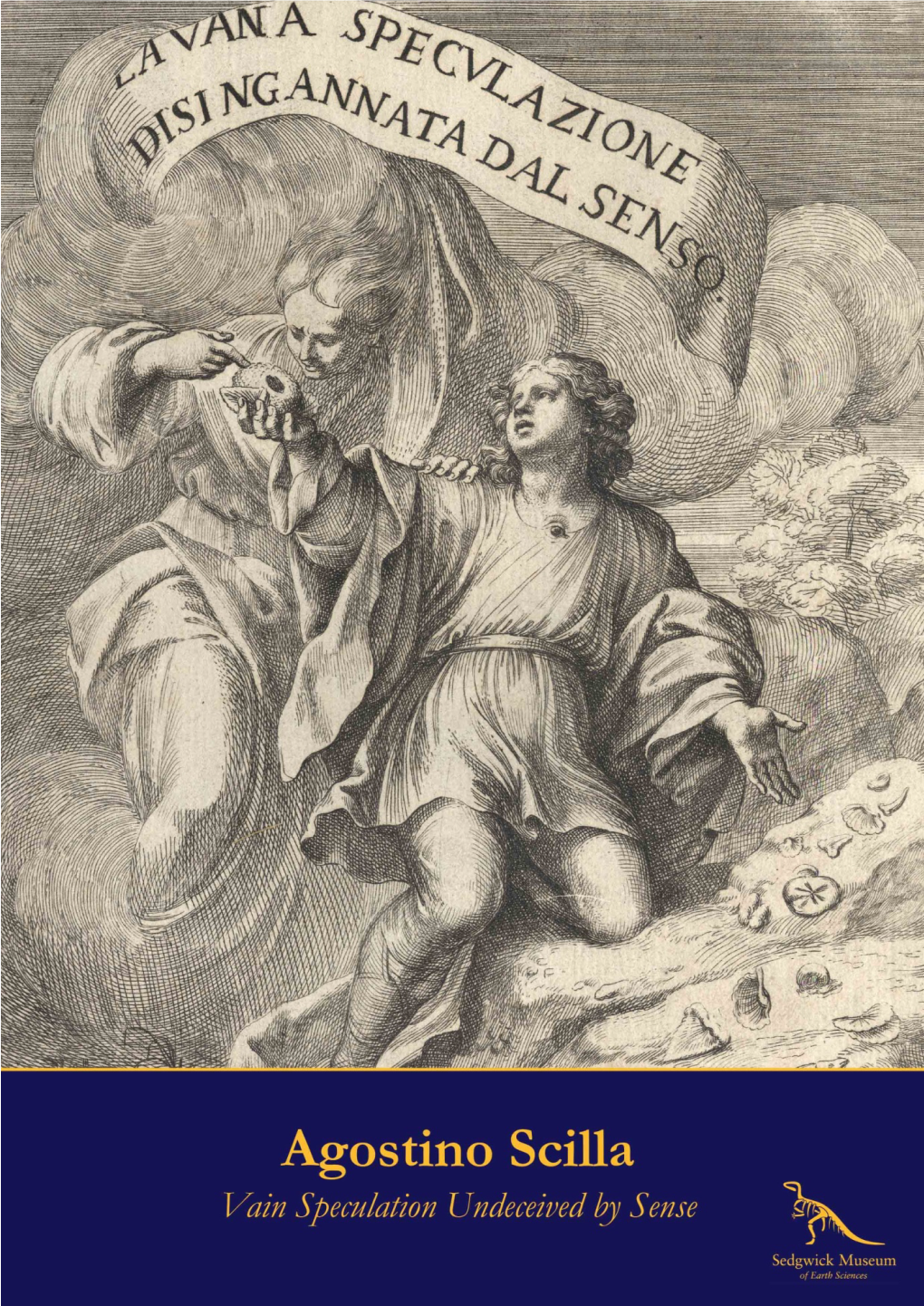

Vain Speculation Undeceived by Sense

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century Yota Batsaki Dumbarton Oaks

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Library Faculty Publications The aM rian Library 2017 The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century Yota Batsaki Dumbarton Oaks Sarah Burke Cahalan University of Dayton, [email protected] Anatole Tchikine Dumbarton Oaks Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_faculty_publications eCommons Citation Batsaki, Yota; Cahalan, Sarah Burke; and Tchikine, Anatole, "The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century" (2017). Marian Library Faculty Publications. Paper 28. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_faculty_publications/28 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The aM rian Library at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Library Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century YOTA BATSAKI SARAH BURKE CAHALAN ANATOLE TCHIKINE Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 2016 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Batsaki, Yota, editor. | Cahalan, Sarah Burke, editor. | Tchikine, Anatole, editor. Title: The botany of empire in the long eighteenth century / Yota Batsaki, Sarah Burke Cahalan, and Anatole Tchikine, editors. Description: Washington, D.C. : Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, [2016] | Series: Dumbarton Oaks symposia and colloquia | Based on papers presented at the symposium “The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century,” held at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., on October 4–5, 2013. | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Fra Tardogotico E Rinascimento: Messina Tra Sicilia E Il Continente

Artigrama, núm. 23, 2008, 301-326 — I.S.S.N.: 0213-1498 Fra Tardogotico e Rinascimento: Messina tra Sicilia e il continente FULVIA SCADUTO* Resumen L’architettura prodotta in ambito messinese fra Quattro e Cinquecento si è spesso prestata ad una valutazione di estraneità rispetto al contesto isolano. L’idea che Messina sia la città più toscana e rinascimentale del sud va probabilmente mitigata: i terremoti che hanno col- pito in modo devastante Messina e la Sicilia orientale hanno probabilmente sottratto numerose prove di una prolungata permanenza del gotico in quest’area condizionando inevitabilmente la lettura degli storici. Bisogna aggiungere che i palazzi di Taormina risultano erroneamente retrodatati e legati al primo Quattrocento. In realtà in questi episodi (ed altri, come quelli di palazzi di Cosenza) il linguaggio tardogotico si manifesta tra Sicilia e Calabria come un feno- meno vitale che si protrae almeno fino ai primi decenni del XVI secolo ed è riscontrabile in mol- teplici fabbriche che la storia ci ha consegnato in resti o frammenti di resti. Il rinascimento si affaccia nel nord est della Sicilia con l’opera di scultori che usano il marmo bianco di Carrara (attivi soprattutto a Messina e Catania) e che sono impegnati nella realizzazione di monumenti, altari, cappelle, portali ecc. Da questo punto di vista Messina segue una parabola analoga a quella di Palermo dove l’architettura tardogotica convive con la scultura rinascimentale. L’influenza del classicismo del marmo, della tradizione tardogotica e il dibattito che si innesca nel duomo di Messina, un cantiere che si andava completando ancora nel corso del primo Cinquecento, sembrano generare nei centri della provincia una serie di sin- golari episodi in cui viene sperimentata la possibilità di contaminazione e ibridazione (portali di Tortorici, Mirto, Mistretta ecc.). -

Enrico Mauceri (1869-1966) Storico Dell’Arte Tra Connoisseurship E Conservazione

ENRICO MAUCERI (1869-1966) STORICO DELL’ARTE TRA CONNOISSEURSHIP E CONSERVAZIONE Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi a cura di Simonetta La Barbera FLACCOVIO EDITORE Stampato con il contributo MIUR ex 60% della prof. Simonetta La Barbera e con il contributo dell’Uni- versità degli Studi di Palermo. Enrico Mauceri (1869-1966). Storico dell’arte tra connoisseurship e conservazione Convegno Internazionale di Studi Palermo, 27-29 settembre 2007 Atti a cura di Simonetta La Barbera FLACCOVIO EDITORE Comitato Scientifico Antonino Buttitta, Maurizio Calvesi, Rosanna Cioffi, Maria Concetta Di Natale, Salvatore Fodale, Gaetano Gullo, Filippo Guttuso, Simonetta La Barbera, Giovanni Ruffino, Gianni Carlo Sciolla, Renato Tomasino. Coordinamento Scientifico Simonetta La Barbera Progetto grafico ed editing Vincenzo Brai Elaborazione delle immagini Nicoletta Di Bella Coordinamento organizzativo Marcella Russo Segreteria organizzativa Roberta Cinà Contatti con i convegnisti Nicoletta Di Bella, Roberta Santoro, Valentina Sarri Facoltà di Lettere, Dipartimento di Studi Storici e Artistici. Viale Delle Scienze. Edificio 12. 90128 Palermo Tel. 0916560265, 0916560333; Fax 0916560310; e-mail: [email protected] Enrico Mauceri (1869-1966) : storico dell’arte tra connoisseurship e conservazione : Convegno internazionale di studi, Palermo 27-29 settembre 2007 / atti a cura di Simonetta La Barbera. – Palermo : Flaccovio, 2009. ISBN 978-88-7804-466-1 1. Mauceri, Enrico – Congressi – Palermo – 2007. I. La Barbera, Simonetta. 700.92 CDD-21 SBN Pal0221869 CIP - Biblioteca centrale della Regione siciliana “Alberto Bombace” Proprietà artistica e letteraria riservata all’Editore a norma della Legge 22 aprile 1941, n. 633. È vie- tata qualsiasi riproduzione totale o parziale anche a mezzo di fotoriproduzione, Legge 22 maggio 1993, n. -

On the Alleged Use of Keplerian Telescopes in Naples in the 1610S

On the Alleged Use of Keplerian Telescopes in Naples in the 1610s By Paolo Del Santo Museo Galileo: Institute and Museum of History of Science – Florence (Italy) Abstract The alleged use of Keplerian telescopes by Fabio Colonna (c. 1567 – 1640), in Naples, since as early as October 1614, as claimed in some recent papers, is shown to be in fact untenable and due to a misconception. At the 37th Annual Conference of the Società Italiana degli Storici della Fisica e dell'Astronomia (Italian Society of the Historians of Physics and Astronomy, SISFA), held in Bari in September 2017, Mauro Gargano gave a talk entitled Della Porta, Colonna e Fontana e le prime osservazioni astronomiche a Napoli. This contribution, which appeared in the Proceedings of the Conference (Gargano, 2019a), was then followed by a paper —actually, very close to the former, which, in turn, is very close to a previous one (Gargano, 2017)— published, in the same year, in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage (Gargano, 2019b). In both of these writings, Gargano claimed that the Neapolitan naturalist Fabio Colonna (c. 1567 – 1640), member of the Accademia dei Lincei, would have made observations with a so-called “Keplerian” or “astronomical” telescope (i.e. with converging eyepiece), in the early autumn of 1614. The events related to the birth and development of Keplerian telescope —named after Johannes Kepler, who theorised this optical configuration in his Dioptrice, published in 1611— are complex and not well-documented, and their examination lies beyond the scope of this paper. However, from a historiographical point of view, the news that someone was already using such a configuration since as early as autumn 1614 for astronomical observations, if true, would have not negligible implications, which Gargano himself does not seem to realize. -

Elenco Definitivo Delle Associazioni Sportive Dilettantistiche 2014 CODICE DENOMINAZIONE FISCALE INDIRIZZO COMUNE CAP PR ' U.S

Elenco definitivo delle Associazioni sportive dilettantistiche 2014 CODICE DENOMINAZIONE FISCALE INDIRIZZO COMUNE CAP PR ' U.S. CASTELLO ' ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA 1 DILETTANTISTICA 02471790242 VIA POZZETTI 3 ARZIGNANO 36071 VI 2 " A.S.D. IL PICCOLO DRAGO " 93079790502 VIA CARLO PORTA 4 PISA 56123 PI " ASSOC. SPORTIVA DILETTANTISTICA AMICI DELLA 3 SCACCHIERA 93028870819 VIA LUCCA 19 ERICE 91016 TP " CIRCOLO TENNIS GORIZIA - ALDO ZACCARELLI - 4 ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA DILET TANTISTICA " 80003400316 VIALE XX SETTEMBRE 3 GORIZIA 34170 GO " FELICEMENTE " ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA 5 DILETTANTISTICA 90029570018 VIA CORDOVA 2 PAVAROLO 10020 TO " GIOCOSPORT " ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA VIA PRIVATA BATTISTA DE 6 DILETTANTISTICA 97447840154 ROLANDI 7 MILANO 20156 MI VIA SALITA S BIAGIO C/O CASA 7 " POLISPORTIVA OTTATI " 91041400655 COMUNA OTTATI 84020 SA 8 "4J S.S.D. S.R.L." 01450670094 VIA VALLE 113 BORGIO VEREZZI 17022 SV 9 "A.S.D. "REAL SAN LUCIDO 96025030782 VIA F GILUIANI SN SAN LUCIDO 87038 CS 10 "A.S.D. BAIANO RUNNERS" 92072170647 VIA NICOLA LITTO BAIANO 83022 AV 11 "A.S.D. FITNESS AL FEMMINILE" 93412030723 VIA LUIGI RICCHIONI 32-34-36 BARI 70124 BA 12 "A.S.D. SPORT SAVONA ARTI MARZIALI" 92089840091 VIA BOVE 22/7 SAVONA 17100 SV 13 "A.S.D.CALCIO GIOVANILE S.PIETRO" 92024520790 VIA GIOVANI NICOTERA 103 SAN PIETRO A MAIDA 88025 CZ "ANTARTICA ASSOCIAZIONE ITALIANA SLEDDOG 14 ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA DILETTANTISTICA" 93074730669 S S 615 SNC L'AQUILA 67100 AQ "ASD CANTERA NAPOLI ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA 15 DILETTANTISTICA" 95153680632 VIA DUOMO 255 NAPOLI 80138 -

Elenco Permanente Degli Enti Iscritti 2020 Associazioni Sportive Dilettantistiche

Elenco permanente degli enti iscritti 2020 Associazioni Sportive Dilettantistiche Prog Denominazione Codice fiscale Indirizzo Comune Cap PR 1 A.S.D. VISPA VOLLEY 00000340281 VIA XI FEBBRAIO SAONARA 35020 PD 2 VOLLEY FRATTE - ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA DILETTANTISTICA 00023810286 PIAZZA SAN GIACOMO N. 18 SANTA GIUSTINA IN COLLE 35010 PD 3 ASSOCIAZIONE CRISTIANA DEI GIOVANI YMCA 00117440800 VIA MARINA 7 SIDERNO 89048 RC 4 UNIONE GINNASTICA GORIZIANA 00128330313 VIA GIOVANNI RISMONDO 2 GORIZIA 34170 GO 5 LEGA NAVALE ITALIANA SEZIONE DI BRINDISI 00138130745 VIA AMERIGO VESPUCCI N 2 BRINDISI 72100 BR 6 SCI CLUB GRESSONEY MONTE ROSA 00143120079 LOC VILLA MARGHERITA 1 GRESSONEY-SAINT-JEAN 11025 AO 7 A.S.D. VILLESSE CALCIO 00143120319 VIA TOMADINI N 4 VILLESSE 34070 GO 8 CIRCOLO NAUTICO DEL FINALE 00181500091 PORTICCIOLO CAPO SAN DONATO FINALE LIGURE 17024 SV 9 CRAL ENRICO MATTEI ASSOCIAZIONE SPORTIVA DILETTANTISTICA 00201150398 VIA BAIONA 107 RAVENNA 48123 RA 10 ASDC ATLETICO NOVENTANA 00213800287 VIA NOVENTANA 136 NOVENTA PADOVANA 35027 PD 11 CIRCOLO TENNIS TERAMO ASD C. BERNARDINI 00220730675 VIA ROMUALDI N 1 TERAMO 64100 TE 12 SOCIETA' SPORTIVA SAN GIOVANNI 00227660321 VIA SAN CILINO 87 TRIESTE 34128 TS 13 YACHT CLUB IMPERIA ASSOC. SPORT. DILETT. 00230200081 VIA SCARINCIO 128 IMPERIA 18100 IM 14 CIRCOLO TENNIS IMPERIA ASD 00238530083 VIA SAN LAZZARO 70 IMPERIA 18100 IM 15 PALLACANESTRO LIMENA -ASSOCIAZIONE DILETTANTISTICA 00256840281 VIA VERDI 38 LIMENA 35010 PD 16 A.S.D. DOMIO 00258370329 MATTONAIA 610 SAN DORLIGO DELLA VALLE 34018 TS 17 U.S.ORBETELLO ASS.SP.DILETTANTISTICA 00269750535 VIA MARCONI 2 ORBETELLO 58015 GR 18 ASSOCIAZIONE POLISPORTIVA D.CAMPITELLO 00270240559 VIA ITALO FERRI 9 TERNI 05100 TR 19 PALLACANESTRO INTERCLUN MUGGIA 00273420323 P LE MENGUZZATO SN PAL AQUILINIA MUGGIA 34015 TS 20 C.R.A.L. -

A Selection of New Arrivals September 2017

A selection of new arrivals September 2017 Rare and important books & manuscripts in science and medicine, by Christian Westergaard. Flæsketorvet 68 – 1711 København V – Denmark Cell: (+45)27628014 www.sophiararebooks.com AMPERE, Andre-Marie. Mémoire. INSCRIBED BY AMPÈRE TO FARADAY AMPÈRE, André-Marie. Mémoire sur l’action mutuelle d’un conducteur voltaïque et d’un aimant. Offprint from Nouveaux Mémoires de l’Académie royale des sciences et belles-lettres de Bruxelles, tome IV, 1827. Bound with 18 other pamphlets (listed below). [Colophon:] Brussels: Hayez, Imprimeur de l’Académie Royale, 1827. $38,000 4to (265 x 205 mm). Contemporary quarter-cloth and plain boards (very worn and broken, with most of the spine missing), entirely unrestored. Preserved in a custom cloth box. First edition of the very rare offprint, with the most desirable imaginable provenance: this copy is inscribed by Ampère to Michael Faraday. It thus links the two great founders of electromagnetism, following its discovery by Hans Christian Oersted (1777-1851) in April 1820. The discovery by Ampère (1775-1836), late in the same year, of the force acting between current-carrying conductors was followed a year later by Faraday’s (1791-1867) first great discovery, that of electromagnetic rotation, the first conversion of electrical into mechanical energy. This development was a challenge to Ampère’s mathematically formulated explanation of electromagnetism as a manifestation of currents of electrical fluids surrounding ‘electrodynamic’ molecules; indeed, Faraday directly criticised Ampère’s theory, preferring his own explanation in terms of ‘lines of force’ (which had to wait for James Clerk Maxwell (1831-79) for a precise mathematical formulation). -

N. 07-Venerdì 13 Febbraio 2015(PDF)

REPUBBLICA ITALIANA . Anno 69°S - Numero 7 . R . E GAZZETTA UFFICIALEU . N DELLA REGIONE SICILIANA G O I SI PUBBLICA DI REGOLA IL VENERDI’ PARTE PRIMA Palermo - Venerdì, 13 febbraio 2015 A Sped.Z in a.p., comma 20/c, art. 2, l. n. 662/96 - Filiale di Palermo L A DIREZIONE, REDAZIONE, AMMINISTRAZIONE: VIA CALTANISSETTA 2-E, 90141 PALERMO INFORMAZIONI TEL. 091/7074930-928-804 - ABBONAMENTI TEL. 091/7074925-931-932 - INSERZIONI TEL. 091/7074936-940L Z - FAX 091/7074927 POSTA ELETTRONICA CERTIFICATA (PEC) [email protected] E Z La Gazzetta Ufficiale della Regione siciliana (Parte prima per intero e i contenuti più rilevanti Idegli altri due fascicoli per estratto) è consultabile presso il sito Internet: http://gurs.regione.sicilia.it accessibile anche dal sitoD ufficiale della Regione www.regione.sicilia.it L E SOMMARIO A L I LEGGI E DECRETI PRESIDENZIALI Assessorato delle attività produttive A C I DECRETO PRESIDENZIALE 16 gennaio 2015. DECRETO 7 gennaioR 2015. Cessazione dalla carica del sindaco, della giunta e del AnnullamentoC E delle note relative all’autorizzazione al consiglio del comune di Mirto e nomina del commissario depositoI degli atti finali di liquidazione e al pagamento straordinario . pag. 3 del compenso finale, revoca dell’incarico conferito ai commissariF M liquidatori della cooperativa Prosperità e Flavoro, con sede in Marsala, e nomina del commissario liquidatore . pag. 11 DECRETO PRESIDENZIALE 16 gennaio 2015. M Cessazione dalla carica del sindaco e della giunta delU comune di Nicosia e nomina del commissario straordina- ODECRETO 14 gennaio 2015. rio . pag. 3 O Liquidazione coatta amministrativa della cooperativa C Bisaccia, con sede in Palermo, e nomina del commissario T liquidatore . -

IL NICODEMO Pace Del Mela Fogli Della Comunità Arrivederci SANTA LUCIA NON E’ I Bambini Del “Progetto Chernobyl ‘98”, Venti in Tutto, Sono in Partenza

Anno VII - Numero 67 pro-manuscripto 6/98 Luglio-Agosto v Parrocchia S. Maria della Visitazione IL NICODEMO Pace del Mela Fogli della Comunità Arrivederci SANTA LUCIA NON e’ I bambini del “Progetto Chernobyl ‘98”, venti in tutto, sono in partenza. Han- no trascorso tra noi un mese intenso di SEMPRE STATA DOV’E’ controlli della salute, di esperienze gioio- se. Grazie a loro, grazie alle famiglie ospi- Una notizia del ti. Tutti siamo cresciuti nell’Amore! Perdichizzi, finora RENATO CALDERONE trascurata, trova riscontro nei GIUDICE GENERALE DI ROMA documenti bbiamo appreso dalla stampa la notizia che il di Franco Biviano Anostro concittadino Re- nato Calderone, magi- adre Francesco Perdichizzi, strato di Cassazione, ha ricevuto nei sacerdote cappuccino mor- mesi scorsi la nomina ad Avvocato Pto a Milazzo nel 1730, in un Generale presso la Corte di Appello manoscritto del 1692 inti- di Roma. Nel congratularci col giu- tolato Melazzo sacro che solo di recen- dice Ninni, come lo chiamano gli te è stato dato alle stampe, ha voluto amici, riteniamo opportuno offrire lasciare memoria della religione dei ai nostri lettori un suo breve curricu- di procedura penale. La sua vasta milazzesi. Tra le altre preziosissime lum. preparazione in campo dottrinario è notizie da lui fornite, ne troviamo una Carmelo Renato Calderone è dimostrata dalla pubblicazione di che riguarda il sito di S. Lucia di Mi- nato, primo di tre figli, a Messina il 2 pregevoli ed apprezzate trattazioni lazzo (oggi del Mela). Egli scrive: gennaio 1936. Ha frequentato le monografiche e dalla collaborazione “Nella valle di Mangarrone sotto S. -

Mitteilungen Des Kunsthistorischen Heft 3 Institutes in Florenz

MITTEILUNGEN DES KUNSTHISTORISCHEN INSTITUTES LXI. BAND — 2019 IN FLORENZ HEFT 3 DES KUNSTHISTORISCHEN INSTITUTES IN FLORENZ MITTEILUNGEN 2019 LXI / 3 LXI. BAND — 2019 MITTEILUNGEN DES KUNSTHISTORISCHEN HEFT 3 INSTITUTES IN FLORENZ Inhalt | Contenuto Redaktionskomitee | Comitato di redazione Aufsätze Saggi Alessandro Nova, Gerhard Wolf, Samuel Vitali _ _ Redakteur | Redattore Samuel Vitali _ 275 _ Carlo Ginzburg Editing und Herstellung | Editing e impaginazione Storia dell’arte, da vicino e da lontano Ortensia Martinez Fucini Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz Max-Planck-Institut _ 287 _ Serena Padovani Via G. Giusti 44, I-50121 Firenze Fra Bartolomeo nella prima attività da frate-pittore e l’inizio del rapporto Tel. 055.2491147, Fax 055.2491155 [email protected] – [email protected] con Raffaello. Due questioni di cronologia www.khi.fi.it/publikationen/mitteilungen Die Redaktion dankt den Peer Reviewers dieses Heftes für ihre Unterstützung | La redazione ringrazia i peer reviewers per la loro collaborazione a questo numero. _ 309 _ Janis Bell Zaccolini, dal Pozzo, and Leonardo’s Writings in Rome and Milan Graphik | Progetto grafico RovaiWeber design, Firenze Produktion | Produzione _ 335 _ Chiara Franceschini Centro Di edizioni, Firenze Mattia Preti’s : Painting, Cult, and Inquisition Madonna della Lettera Die erscheinen jährlich in drei Heften und in Malta, Messina, and Rome könnenMitteilungen im Abonnement oder in Einzelheften bezogen werden durch | Le escono con cadenza quadrimestrale e possonoMitteilungen essere ordinate in abbonamento o singolarmente presso: Centro Di edizioni, Via dei Renai 20r _ 365 _ Gabriella Cianciolo Cosentino I-50125 Firenze, Tel. 055.2342666, Dislocazione, musealizzazione e ricezione dei reperti pompeiani: [email protected]; www.centrodi.it. -

The Opposite Poles of a Debate - Lapides Figurati and the Accademia Dei Lincei1 Citation: A

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Opposite Poles of a Debate - Lapides figurati and the Accademia dei Lincei1 Citation: A. Ottaviani (2021) The Oppo- site Poles of a Debate - Lapides figu- rati and the Accademia dei Lincei. Substantia 5(1) Suppl.: 19-28. doi: Alessandro Ottaviani 10.36253/Substantia-1275 Università di Cagliari, Dipartimento di Pedagogia, Psicologia, Filosofia, via Is Mirrionis Copyright: © 2021 A. Ottaviani. This is 1, 09123 Cagliari an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. The essay analyses the research carried out by some members of the Acca- Creative Commons Attribution License, demia dei Lincei on lapides figurati, namely by Fabio Colonna on animal fossils, and by which permits unrestricted use, distri- Federico Cesi and Francesco Stelluti on plant fossils; the aim is to show the role played bution, and reproduction in any medi- by the Accademia dei Lincei in establishing during the second half of the seventeenth um, provided the original author and century the opposite poles of the debate on the lapides figurati, on the one hand as source are credited. chronological indices of a past world and, on the other, as sudden outcome of the vis Data Availability Statement: All rel- vegetativa. evant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files. Keywords: Accademia dei Lincei, Fabio Colonna, Federico Cesi, Francesco Stelluti, Fossils, lapides figurati, Rationes seminales. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. 1. -

Annals Cover 5

THIS VOLUME CONTAINS A BIBLIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF DECEASED BRYOZOOLOGISTS WHO RESEARCHED FOSSIL AND LIVING BRYOZOANS. ISBN 978-0-9543644-4-9 INTERNATIONAL 1f;��'f ' ;� BRYOZOOLOGY � EDITED BY ASSOCIATION PATRICK N. WYSE JACKSON & MARY E. SPENCER JONES i Annals of Bryozoology 5 ii iii Annals of Bryozoology 5: aspects of the history of research on bryozoans Edited by Patrick N. Wyse Jackson & Mary E. Spencer Jones International Bryozoology Association 2015 iv © The authors 2015 ISBN 978-0-9543644-4-9 First published 2015 by the International Bryozoology Association, c/o Department of Geology, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland. Printed in Ireland. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or stored in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, photocopying, recording or by any other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Cover illustrations Front: Photographic portraits of twelve bryozoologists: Top row (from left): Arthur William Waters (England); Hélène Guerin-Ganivet (France); Edward Oscar Ulrich (USA); Raymond Carroll Osburn (USA); Middle row: Ferdinand Canu (France); Antonio Neviani (Italy); Georg Marius Reinald Levinsen (Denmark); Edgar Roscoe Cumings (USA); Bottom row: Sidney Frederic Harmer (England); Anders Hennig (Sweden); Ole Nordgaard (Norway); Ray Smith Bassler (USA). Originals assembled by Ferdinand Canu and sent in a frame to Edgar Roscoe Cumings in and around 1910-1920 (See Patrick N. Wyse Jackson (2012) Ferdinand Canu’s Gallery of Bryozoologists. International Bryozoology Association Bulletin, 8(2), 12-13. Back: Portion of a plate from Alicide d’Orbigny’s Paléontologie française (1850–1852) showing the Cretaceous bryozoan Retepora royana. Background: Structure of Flustra from Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665).