Winter 2018 Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Variable Holocene Deformation Above a Shallow Subduction Zone Extremely Close to the Trench

ARTICLE Received 24 Nov 2014 | Accepted 22 May 2015 | Published 30 Jun 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8607 OPEN Variable Holocene deformation above a shallow subduction zone extremely close to the trench Kaustubh Thirumalai1,2, Frederick W. Taylor1, Chuan-Chou Shen3, Luc L. Lavier1,2, Cliff Frohlich1, Laura M. Wallace1, Chung-Che Wu3, Hailong Sun3,4 & Alison K. Papabatu5 Histories of vertical crustal motions at convergent margins offer fundamental insights into the relationship between interplate slip and permanent deformation. Moreover, past abrupt motions are proxies for potential tsunamigenic earthquakes and benefit hazard assessment. Well-dated records are required to understand the relationship between past earthquakes and Holocene vertical deformation. Here we measure elevations and 230Th ages of in situ corals raised above the sea level in the western Solomon Islands to build an uplift event history overlying the seismogenic zone, extremely close to the trench (4–40 km). We find marked spatiotemporal heterogeneity in uplift from mid-Holocene to present: some areas accrue more permanent uplift than others. Thus, uplift imposed during the 1 April 2007 Mw 8.1 event may be retained in some locations but removed in others before the next megathrust rupture. This variability suggests significant changes in strain accumulation and the interplate thrust process from one event to the next. 1 Institute for Geophysics, Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas at Austin, J. J. Pickle Research Campus, Building 196, 10100 Burnet Road (R2200), Austin, Texas 78758, USA. 2 Department of Geological Sciences, Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas at Austin, 1 University Station C9000, Austin, Texas 78712, USA. -

FWC Sentinel Site Report June 2018

Investigating the Ongoing Coral Disease Outbreak in the Florida Keys: Collecting Corals to Diagnose the Etiological Agent(s) and Establishing Sentinel Sites to Monitor Transmission Rates and the Spatial Progression of the Disease. Florida Department of Environmental Protection Award Final Report FWC: FWRI File Code: F4364-18-18-F William Sharp & Kerry Maxwell Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission Fish & Wildlife Research Institute June 25, 2018 Project Title: Investigating the ongoing coral disease outbreak in the Florida Keys: collecting corals to diagnose the etiological agent(s) and establishing sentinel sites to monitor transmission rates and the spatial progression of the disease. Principal Investigators: William C. Sharp and Kerry E. Maxwell Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission Fish & Wildlife Research Institute 2796 Overseas Hwy., Suite 119 Marathon FL 33050 Project Period: 15 January 2018 – 30 June 2018 Reporting Period: 21 April 2018 – 15 June 2018 Background: Disease is recognized as a major cause of the progressive decline in reef-building corals that has contributed to the general decline in coral reef ecosystems worldwide (Jackson et al. 2014; Hughes et al. 2017). The first reports of coral disease in the Florida Keys emerged in the 1970’s and numerous diseases have been documented with increasing frequency (e.g., Porter et al., 2001). Presently, the Florida Reef Tract (FRT) is experiencing one of the most widespread and virulent disease outbreaks on record. This outbreak has resulted in the mortality of thousands of colonies of at least 20 species of scleractinian coral, including primary reef builders and species listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act. -

III. Species Richness and Benthic Cover

2009 Quick Look Report: Miller et al. III. Species Richness and Benthic Cover Background The most species-rich marine communities probably occur on coral reefs and this pattern is at least partly due to the diversity of available habitats and the degree to which species are ecologically restricted to particular niches. Coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific and Caribbean in particular are usually thought to hold the greatest diversity of marine life at several levels of biological diversity. Diversity on coral reefs is strongly influenced by environmental conditions and geographic location, and variations in diversity can be correlated with differences in reef structure. For example, shallow and mid-depth fore-reef habitats in the Caribbean were historically dominated by largely mono-specific zones of just two Acropora species, while the Indo-Pacific has a much greater number of coral species and growth forms. Coral reefs are in a state of decline worldwide from multiple stressors, including physical impacts to habitat, changes in water quality, overfishing, disease outbreaks, and climate change. Coral reefs in a degraded state are often characterized by one or more signs, including low abundances of top-level predators, herbivores, and reef-building corals, but higher abundances of non-hermatypic organisms such as seaweeds. For the Florida Keys, there is little doubt that areas historically dominated by Acropora corals, particularly the shallow (< 6 m) and deeper (8-15 m) fore reef, have changed substantially, largely due to Caribbean-wide disease events and bleaching. However, debate continues regarding other causes of coral reef decline, thus often making it difficult for resource managers to determine which courses of action to take to minimize localized threats in lieu of larger-scale factors such as climate change. -

Modeling Larval Connectivity Among Coral Habitats, Acropora Palmata

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2007 Modeling larval connectivity among coral habitats, Acropora palmata populations, and marine protected areas in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Christopher John Higham University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Higham, Christopher John, "Modeling larval connectivity among coral habitats, Acropora palmata populations, and marine protected areas in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2213 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modeling Larval Connectivity among Coral Habitats, Acropora palmata Populations, and Marine Protected Areas in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary by Christopher John Higham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Geography College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Paul Zandbergen, Ph.D. Jayajit Chakraborty, Ph.D. Susan Bell, Ph.D. Data of Approval: April 10, 2007 Keywords: GIS, ArcGIS, TauDEM, D∞ flow routing, ocean currents, flow direction, contributing flow, upstream -

Tortugas Ecological Reserve

Strategy for Stewardship Tortugas Ecological Reserve U.S. Department of Commerce DraftSupplemental National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Environmental National Ocean Service ImpactStatement/ Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management DraftSupplemental Marine Sanctuaries Division ManagementPlan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), working in cooperation with the State of Florida, the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, proposes to establish a 151 square nautical mile “no- take” ecological reserve to protect the critical coral reef ecosystem of the Tortugas, a remote area in the western part of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. The reserve would consist of two sections, Tortugas North and Tortugas South, and would require an expansion of Sanctuary boundaries to protect important coral reef resources in the areas of Sherwood Forest and Riley’s Hump. An ecological reserve in the Tortugas will preserve the richness of species and health of fish stocks in the Tortugas and throughout the Florida Keys, helping to ensure the stability of commercial and recreational fisheries. The reserve will protect important spawning areas for snapper and grouper, as well as valuable deepwater habitat for other commercial species. Restrictions on vessel discharge and anchoring will protect water quality and habitat complexity. The proposed reserve’s geographical isolation will help scientists distinguish between natural and human-caused changes to the coral reef environment. Protecting Ocean Wilderness Creating an ecological reserve in the Tortugas will protect some of the most productive and unique marine resources of the Sanctuary. Because of its remote location 70 miles west of Key West and more than 140 miles from mainland Florida, the Tortugas region has the best water quality in the Sanctuary. -

Distribution of Clionid Sponges in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), 2001-2003

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Distribution of Clionid Sponges in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), 2001-2003 Michael K. Callahan University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Callahan, Michael K., "Distribution of Clionid Sponges in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), 2001-2003" (2005). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2803 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Distribution of Clionid Sponges in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), 2001-2003 by Michael K. Callahan A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Biological Oceanography College of Marine Science University of South Florida Major Professor: Pamela Hallock Muller, Ph.D. Carl R. Beaver, Ph.D. Walter C. Jaap, B.S. Kendra L. Daly, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 28, 2005 Keywords: Bioerosion, Cliona delitrix, Coral Reefs, Monitoring © Copyright 2005, Michael K. Callahan AKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. Pamela Hallock Muller for her tireless effort and patience. I would also like to thank and acknowledge my committee members Dr. Carl Beaver, Walter Jaap, and Dr. Kendra Daly and the entire CREMP research team for their help and guidance. -

Anemones, Form Associations with Several Invertebrates Such As Cleaner Shrimps (Limbaugh Et Al

2009 Quick Look Report: Miller et al. VII. Anemone and Corallimorpharian Density Background Most historical and recent studies of Caribbean reef fauna, including those in the Florida Keys, have generally focused on either stony corals or fishes. This is not surprising, given that corals are primary framework builders, while fishes, along with certain shellfish species (e.g. queen conch and spiny lobster) are generally the most economically important fishery targets. In the Florida Keys, however, commercial marine-life fisheries and aquarium hobbyists remove an incredible diversity and number of invertebrates and fishes (Bohnsack et al. 1994). Otherwise known as the marine ornamental fishery, aquarium fisheries target a diversity of fish, invertebrate, and algal species, in addition to sand and live rock from West Palm Beach to Key West (FWCC 2001). State and Federal waters near Key West and Marathon in the Florida Keys constitute 94% of the total fishes and invertebrates removed in southeast Florida for the marine aquarium trade. Commercial data do not include an undocumented effort from recreational fishers, nor are data available concerning species abundance patterns and population trends relative to fishing effort (NOAA 1996). Key Largo has been protected from marine aquarium trade species collection since 1960 in John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, followed by the protection in federal waters in 1975 with the establishment of Key Largo National Marine Sanctuary. The Looe Key area has been protected since 1981, as well as Everglades National Park (Florida Bay), portions of the Dry Tortugas area, Biscayne National Park, and Fish and Wildlife Service management areas. There is a paucity of basic ecological information for most Florida Keys anemone and corallimorpharian (Cnidaria, Anthozoa) species, and even fewer studies have explored the population effects of exploitation. -

Taming the Reef the Coast Survey in the Keys

Taming the Reef The Coast Survey in the Keys James Tilghman —No portion of the coast of the United States has stronger claims than this to a speedy and minute survey, whether we regard the dangers to navigation, the amount of commerce which passes it, or the various localities of the Union interest ed in the trading vessels. Alexander Dallas Bache Superintendent of the Coast Survey, 18u9 As Ponce de Leon sailed south along the coast of Florida in 1513, he encountered the Gulf Stream where it runs close to shore north of Lake Worth Inlet. Swept back bv a current his log describes as "more powerful than the wind,” it took weeks for the small fleet to regroup. Ponce de Leon’s pilot (navigator), Anton de Alaminos, remembered the ordeal six years later when he was aboard Hernando Cortes' flagship carrying the first Aztec gold and Cortes' bid to be governor of Mexico back to Spain. Speed was of the essence, and it was feared the lone ship might be inter cepted by the governor of Cuba, a rival, if it made for the Atlantic through the Old Bahama Channel, the established route that ran between Cuba and the Great Bahama Bank. So Alaminos decided to round Florida and head north instead, convinced that a current as strong as the one he had experienced would lead to open water. He was right, of course. The Gulf Stream not only carried him to the Atlantic but half wav back to Spain.1 This "New Bahama Channel," also known as the Gulf or Straits of Florida, became the most important sea lane in the New World—the route home for thousands of Spanish and European ships, and later the 6 TEQUESTA wav around Florida for American ships sailing between ports on the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts. -

A Case Study: Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and Update on the Sanctuary Nomination Process

A Case Study: Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary And Update on the Sanctuary Nomination Process Presentation to: Our Florida Reefs Program August 20, 2014 NOVA Southeastern University Dania Beach, Florida Billy D. Causey, Ph.D. Southeast Regional Director NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Organization Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Marine Protected Areas Definition of a Marine Protected Area: Defined by the IUCN (The World Conservation Union) as: "any area of intertidal or subtidal terrain, together with its overlying water and associated flora, fauna, historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by law or other effective means to protect part or all of the enclosed environment.” Reference: Guidelines for Establishing Marine Protected Areas (Kelleher/Kenchington, 1991) What are National Marine Sanctuaries? “Areas of the marine environment with special conservation, recreational, ecological, historical, cultural, archeological, or esthetic qualities…” National Marine Sanctuary Act (sec. 301) Multiple-use Program National Marine Sanctuaries Act “To maintain, restore, and enhance living resources ... and to facilitate to the extent possible all public and private uses of the resources of these marine areas………” The National Marine Sanctuaries Act Mandate “…to identify and designate as national marine sanctuaries areas of the marine environment which are of special national significance and to manage these areas -

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Water Quality Monitoring

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Water Quality Monitoring Project 1998 Annual Report Principal Investigators Ronald D. Jones and Joseph N. Boyer Southeast Environmental Research Program Florida International University Miami, FL 33199 US EPA Contract #X994621-94-0 This is contribution #81 of the Southeast Environmental Research Program at Florida International University. Table of Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY II. PROJECT BACKGROUND III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION IV. LIST OF APPENDICES I. Executive Summary This report serves as a summary of our efforts to date in the execution of the water quality monitoring program for the FKNMS. Last year we added 4 sampling sites and made minor adjustments to six others to establish water quality sampling within some of the Sanctuary Preservation Areas and Ecological Reserves. We have received 11 requests for data by outside researchers working in the FKNMS of which one has resulted in a master's thesis. Two scientific manuscripts have been submitted for publication: one is a book chapter in Linkages Between Ecosystems: the South Florida Hydroscape, St. Lucie Press; the other is in special issue of Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science on visualization in coastal marine science. Another manuscript is being prepared in conjunction with the FKNMS seagrass monitoring program for submission next year. We also maintain a web site at http://www.fiu.edu/~serp/jrpp/wqmn/ datamaps/datamaps.html where data from the FKNMS is integrated with the other parts of the SERP water quality network (Florida Bay, Whitewater Bay, Biscayne Bay, Ten Thousand Islands, and SW Florida Shelf) and displayed as downloadable contour maps. The period of record for this report is March 95 - October 98 and includes data from 13 quarterly sampling events at 154 stations within the FKNMS including the Dry Tortugas National Park. -

Implementing Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary's Regulatory And

Implementing Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary’s Regulatory and Marine Zoning Action Plans A Staff Summary for Sanctuary Advisory Council Review August 16, 2011 Table of Contents SECTION 1. WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT? .................................................................................... 1 SECTION 2. WHAT IS THE FLORIDA KEYS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY? .......................................................... 1 SECTION 3. WHY DO WE NEED REGULATIONS IN THE SANCTUARY? ..................................................................... 4 SECTION 4. WHY IS THE SANCTUARY UNDERTAKING A COMPREHENSIVE REGULATORY REVIEW? ....................... 5 SECTION 5. WHAT WOULD A COMPREHENSIVE REGULATORY REVIEW ENTAIL? ................................................... 7 SECTION 6. WHAT ARE THE EXISTING REGULATIONS IN THE SANCTUARY? ........................................................... 9 SECTION 6.1 REGULATIONS THAT APPLY SANCTUARY-WIDE ................................................................................................. 10 SECTION 6.2 MARINE ZONES IN THE FKNMS ................................................................................................................... 10 SECTION 6.3 REGULATIONS SPECIFIC TO DESIGNATED MARINE ZONES ................................................................................... 12 SECTION 7. WHAT GUIDANCE HAS THE SANCTUARY ADVISORY COUNCIL PROVIDED ON THE REGULATORY AND MARINE ZONING ACTION PLANS? ....................................................................................................................... -

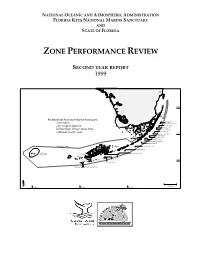

Zone Performance Review

NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION FLORIDA KEYS NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY AND STATE OF FLORIDA ZONE PERFORMANCE REVIEW SECOND YEAR REPORT 1999 Miami 25°30 Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Carysfort/ •Zone types: South Carysfort (b) •a) Ecological Reserve The Elbow (b) Dry Rocks (b) •b) Sanctuary Preservation Area Grecian Rocks (b) French Reef (b) •c) Research-only Area 25°00 Molasses Reef (b) Conch Reef (c) Cheeca Rocks (b) Conch Reef (b) Davis Reef (b) Hen and Chickens (b) Alligator Reef (b) Sanctuary boundary Marathon Tennessee Reef (c) Coffins Patch (b) Dry Tortugas Sombrero Key (b) National Park Key West Newfound Harbor (b) Western Eastern Sambos (c) Looe Key (c) 24°30 Sambos (a) Looe Key (b) Sand Key (b) Rock Key (b) Eastern Dry Rocks (b) N 25 Kilometers 83° 00 82° 00 81° 00 Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Zone Performance Report – Year 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Similar to last year’s findings, Year 2 monitoring results indicated that mobile, heavily exploited species such as lobster, snapper and grouper continue to show increases in the Sanctuary’s 23 no-take areas. Specifically, legal- sized spiny lobsters were more abundant in Sanctuary Preservation Areas (SPAs) than in reference sites of comparable habitat. The average size of legal lobsters was larger in the no-take zones than in reference sites. Also, catch rates (number of lobsters per trap) were higher within the Western Sambo Ecological Reserve than within two adjacent fished areas during both the closed and open fishing seasons. Preliminary analysis of reef fish abundance data from one monitoring program showed that mean densities (number of individuals per sample) for three of four exploited fish species are higher in the SPAs than in fished reference sites.