Tortugas Ecological Reserve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skeletal Development and Mineralization Pattern of The

e Rese tur arc ul h c & a u D q e A v e f l o o Mesa-Rodríguez et al., J Aquac Res Development 2014, 5:6 l p a m n Journal of Aquaculture r e u n o t DOI: 10.4172/2155-9546.1000266 J ISSN: 2155-9546 Research & Development Research Article OpenOpen Access Access Skeletal Development and Mineralization Pattern of the Vertebral Column, Dorsal, Anal and Caudal Fin Complex in Seriola Rivoliana (Valenciennes, 1833) Larvae Mesa-Rodríguez A*, Hernández-Cruz CM, Socorro JA, Fernández-Palacios H, Izquierdo MS and Roo J Aquaculture Research Group, Science and Technology Park, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, P. O. Box 56, 35200 Telde, Canary Islands, Spain Abstract Bone and fins development in Seriola rivoliana were studied from cleared and stained specimens from 3 to 33 days after hatching. The vertebral column began to mineralize in the neural arches at 4.40 ± 0.14 mm Standard Length (SL), continued with the haemal arches and centrums following a cranial-caudal direction. Mineralization of the caudal fin structures started with the caudal rays by 5.12 ± 0.11 mm SL, at the same time that the notochord flexion occurs. The first dorsal and anal fin structures were the hard spines (S), and lepidotrichium (R) by 8.01 ± 0.26 mm SL. The metamorphosis was completed by 11.82 ± 0.4 mm SL. Finally, the fin supports (pterygiophores) and the caudal fins were completely mineralized by 16.1 ± 0.89 mm SL. In addition, the meristic data of 23 structures were provided. -

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico And

A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes THIRD EDITION GSMFC No. 300 NOVEMBER 2020 i Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission Commissioners and Proxies ALABAMA Senator R.L. “Bret” Allain, II Chris Blankenship, Commissioner State Senator District 21 Alabama Department of Conservation Franklin, Louisiana and Natural Resources John Roussel Montgomery, Alabama Zachary, Louisiana Representative Chris Pringle Mobile, Alabama MISSISSIPPI Chris Nelson Joe Spraggins, Executive Director Bon Secour Fisheries, Inc. Mississippi Department of Marine Bon Secour, Alabama Resources Biloxi, Mississippi FLORIDA Read Hendon Eric Sutton, Executive Director USM/Gulf Coast Research Laboratory Florida Fish and Wildlife Ocean Springs, Mississippi Conservation Commission Tallahassee, Florida TEXAS Representative Jay Trumbull Carter Smith, Executive Director Tallahassee, Florida Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas LOUISIANA Doug Boyd Jack Montoucet, Secretary Boerne, Texas Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Baton Rouge, Louisiana GSMFC Staff ASMFC Staff Mr. David M. Donaldson Mr. Bob Beal Executive Director Executive Director Mr. Steven J. VanderKooy Mr. Jeffrey Kipp IJF Program Coordinator Stock Assessment Scientist Ms. Debora McIntyre Dr. Kristen Anstead IJF Staff Assistant Fisheries Scientist ii A Practical Handbook for Determining the Ages of Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Coast Fishes Third Edition Edited by Steve VanderKooy Jessica Carroll Scott Elzey Jessica Gilmore Jeffrey Kipp Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission 2404 Government St Ocean Springs, MS 39564 and Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission 1050 N. Highland Street Suite 200 A-N Arlington, VA 22201 Publication Number 300 November 2020 A publication of the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award Number NA15NMF4070076 and NA15NMF4720399. -

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Dry Tortugas National Park

LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Cover Photograph: Aerial view of Fort Jefferson on Garden Key (fore- ground) and Bush Key (background). COMPREHENSIVE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Prepared by: Department of Interpretive Planning Harpers Ferry Design Center and the Interpretive Staff of Dry Tortugas National Park and Everglades National Park INTRODUCTION About 70 miles west of Key West, Florida, lies a string of seven islands called the Dry Tortugas. These sand and coral reef islands, or keys, along with 100 square miles of shallow waters and shoals that surround them, make up Dry Tortugas National Park. Here, clear views of water and sky extend to the horizon, broken only by an occasional island. Below and above the horizon line are natural and historical treasures that continue to beckon and amaze those visitors who venture here. Warm, clear, shallow, and well-lit waters around these tropical islands provide ideal conditions for coral reefs. Tiny, primitive animals called polyps live in colonies under these waters and form skeletons from cal- cium carbonate which, over centuries, create coral reefs. These reef ecosystems support a wealth of marine life such as sea anemones, sea fans, lobsters, and many other animal and plant species. Throughout these fragile habitats, colorful fishes swim, feed, court, and thrive. Sea turtles−−once so numerous they inspired Spanish explorer Ponce de León to name these islands “Las Tortugas” in 1513−−still live in these waters. Loggerhead and Green sea turtles crawl onto sand beaches here to lay hundreds of eggs. -

Dry Tortugas U.S

National Park Service Dry Tortugas U.S. Department of the Interior Dry Tortugas National Park P.O. Box 6208 Key West, FL 33041 Park Regulations Welcome to the Park Welcome to Dry Tortugas National Park! This is a special place, and requires care from all who visit. The following is a summary of those regulations most important to park visitors. These regulations are necessary for protecting the fragile natural and historical features within Dry Tortugas National Park, and for ensuring your safety. When in doubt, ask park staff for additional information. Have a safe and enjoyable visit! Public Use Areas and Fort Jefferson and Garden Key Bush Key Closures The fort interior is open sunrise to sunset. Pets, food, Closed January 16-October 14 for bird nesting. and drinks, are not permitted inside the fort. Service and residential areas are closed to the public. The Hospital & Long Keys moat is closed to all entries and activities. The Special Closed year round. Visitors should remain 100 feet Protection Zones for shark breeding and corals on off shore of all closed islands. the east and southeast side of Garden Key harbor are closed to all vessels. Loggerhead Key Open year round during daylight hours only. Middle and East Key Dock and all structures are closed to public use. Closed April 1- October 15 for turtle nesting. Exploring on foot is limited to developed trails and shoreline between water and high tide line only. Fishing Important Reminders Park Areas Closed to Fishing All State of Florida saltwater fishing laws and regula- All fishing is prohibited within the Research Natural tions apply except as modified below. -

Sample Itinerary: Dry Tortugas – One Week*

Sample Itinerary: Dry Tortugas – One Week* Day 1 – Depart out of Marathon in the evening and sail to the Dry Tortugas. (107 NM) It will take anywhere from 12 to 16 hours to make this passage. You should try to arrive in day light hours so that your approach is easier. Day 2 – Arrive at the island group known as the Dry Tortugas. This is the most isolated and least visited national park in the United States. You should plan to spend two nights here but if the weather deteriorates be flexible enough to cut it short and head back to Key West. There are no services out on these islands so you should plan to be self sufficient while in this remote area. Day 3 – Go ashore on Garden Key and tour Fort Jefferson National Monument. This was originally built in the mid 1800’s as a military fort to be used by Union forces during the Civil War. The fort was converted to a prison whose most famous inmate was Dr. Mudd of Lincoln’s time. Day 4 – Snorkel the reefs surrounding the islands. Go ashore on Loggerhead Key and/or Hospital Key for a cookout, just be sure to clean up well and leave as little of a footprint as possible. Bush Key offers great bird watching from your yacht. Bush Key is a bird sanctuary and landing is prohibited. Day 5 – Depart the Dry Tortugas early in the morning and sail to the uninhabited island group of the Marquesas. (44 NM) Be careful of Rebecca Shoal on the way and arrive before dark. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Bookletchart™ Intracoastal Waterway – Bahia Honda Key to Sugarloaf Key NOAA Chart 11445

BookletChart™ Intracoastal Waterway – Bahia Honda Key to Sugarloaf Key NOAA Chart 11445 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the The tidal current at the bridge has a velocity of about 1.4 to 1.8 knots. Wind effects modify the current velocity considerably at times; easterly National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration winds tend to increase the northward flow and westerly winds the National Ocean Service southward flow. Overfalls that may swamp a small boat are said to occur Office of Coast Survey near the bridge at times of large tides. (For predictions, see the Tidal Current Tables.) www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov Route.–A route with a reported controlling depth of 8 feet, in July 1975, 888-990-NOAA from the Straits of Florida via the Moser Channel to the Gulf of Mexico is as follows: From a point 0.5 mile 336° from the center of the bridge, What are Nautical Charts? pass 200 yards west of the light on Red Bay Bank, thence 0.4 mile east of the light on Bullard Bank, thence to a position 3 miles west of Northwest Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show Cape of Cape Sable (chart 11431), thence to destination. water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Bahia Honda Channel (Bahia Honda), 10 miles northwestward of more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and Sombrero Key and between Bahia Honda Key on the east and Scout efficient navigation. -

Collier Miami-Dade Palm Beach Hendry Broward Glades St

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission F L O R ID A 'S T U R N P IK E er iv R ee m Lakewood Park m !( si is O K L D INDRIO ROAD INDRIO RD D H I N COUNTY BCHS Y X I L A I E O W L H H O W G Y R I D H UCIE BLVD ST L / S FT PRCE ILT SRA N [h G Fort Pierce Inlet E 4 F N [h I 8 F AVE "Q" [h [h A K A V R PELICAN YACHT CLUB D E . FORT PIERCE CITY MARINA [h NGE AVE . OKEECHOBEE RA D O KISSIMMEE RIVER PUA NE 224 ST / CR 68 D R !( A D Fort Pierce E RD. OS O H PIC R V R T I L A N N A M T E W S H N T A E 3 O 9 K C A R-6 A 8 O / 1 N K 0 N C 6 W C W R 6 - HICKORY HAMMOCK WMA - K O R S 1 R L S 6 R N A E 0 E Lake T B P U Y H D A K D R is R /NW 160TH E si 68 ST. O m R H C A me MIDWAY RD. e D Ri Jernigans Pond Palm Lake FMA ver HUTCHINSON ISL . O VE S A t C . T I IA EASY S N E N L I u D A N.E. 120 ST G c I N R i A I e D South N U R V R S R iv I 9 I V 8 FLOR e V ESTA DR r E ST. -

Coast Guard, DHS § 7.100

Coast Guard, DHS § 7.100 the easternmost extremity of Black- (e) A line drawn across the seaward beard Island at Northeast Point. extremity of the Sebastian Inlet Jet- (d) A line drawn from the southern- ties. most extremity of Blackbeard Island to (f) A line drawn from the seaward ex- latitude 31°19.4′ N. longitude 81°11.5′ W. tremity of the Fort Pierce Inlet North (Doboy Sound Lighted Buoy ‘‘D’’); Jetty to latitude 27°28.5′ N. longitude thence to latitude 31°04.1′ N. longitude 80°16.2′ W. (Fort Pierce Inlet Lighted 81°16.7′ W. (St. Simons Lighted Whistle Whistle Buoy ‘‘2’’); thence to the tank Buoy ‘‘ST S’’). located in approximate position lati- tude 27°27.2′ N. longitude 80°17.2′ W. § 7.85 St. Simons Island, GA to Little (g) A line drawn from the seaward ex- Talbot Island, FL. tremity of St. Lucie Inlet north jetty (a) A line drawn from latitude 31°04.1′ to latitude 27°10′ N. longitude 80°08.4′ N. longitude 81°16.7′ W. (St. Simons W. (St. Lucie Inlet Entrance Lighted Lighted Whistle Buoy ‘‘ST S’’) to lati- Whistle Buoy ‘‘2’’); thence to Jupiter tude 30°42.7′ N. longitude 81°19.0′ W. (St. Island bearing approximately 180° true. Mary’s Entrance Lighted Whistle Buoy (h) A line drawn from the seaward ex- ‘‘1’’); thence to Amelia Island Light. tremity of Jupiter Inlet North Jetty to (b) A line drawn from the southern- the northeast extremity of the con- most extremity of Amelia Island to crete apron on the south side of Jupiter latitude 30°29.4′ N. -

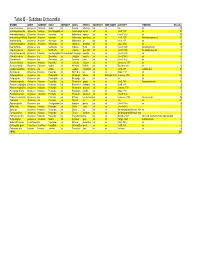

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia BINOMEN ORDER SUBORDER FAMILY SUBFAMILY GENUS SPECIES SUBSPECIES COMN_NAMES AUTHORITY SYNONYMS #Records Acanella arbuscula Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Acanella arbuscula n/a n/a n/a n/a 59 Acanthogorgia armata Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae n/a Acanthogorgia armata n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 95 Anthomastus agassizii Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 35 Anthomastus grandiflorus Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus grandiflorus n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 Anthomastus purpureus 37 Anthomastus sp. Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus sp. n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 1 Anthothela grandiflora Alcyonacea Scleraxonia Anthothelidae n/a Anthothela grandiflora n/a n/a (Sars, 1856) n/a 24 Capnella florida Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella florida n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya florida 44 Capnella glomerata Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella glomerata n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya glomerata 4 Chrysogorgia agassizii Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae Chrysogorgiidae Chrysogorgia agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1883) n/a 2 Clavularia modesta Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia modesta n/a n/a (Verrill, 1987) n/a 6 Clavularia rudis Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia rudis n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 1 Gersemia fruticosa Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Gersemia fruticosa n/a n/a Marenzeller, 1877 n/a 3 Keratoisis flexibilis Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Keratoisis flexibilis n/a n/a Pourtales, 1868 n/a 1 Lepidisis caryophyllia Alcyonacea n/a Isididae n/a Lepidisis caryophyllia n/a n/a Verrill, 1883 Lepidisis vitrea 13 Muriceides sp. -

Guide to the Identification of Precious and Semi-Precious Corals in Commercial Trade

'l'llA FFIC YvALE ,.._,..---...- guide to the identification of precious and semi-precious corals in commercial trade Ernest W.T. Cooper, Susan J. Torntore, Angela S.M. Leung, Tanya Shadbolt and Carolyn Dawe September 2011 © 2011 World Wildlife Fund and TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9693730-3-2 Reproduction and distribution for resale by any means photographic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any parts of this book, illustrations or texts is prohibited without prior written consent from World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Reproduction for CITES enforcement or educational and other non-commercial purposes by CITES Authorities and the CITES Secretariat is authorized without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit WWF and TRAFFIC North America. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The designation of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF, TRAFFIC, or IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint program of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Cooper, E.W.T., Torntore, S.J., Leung, A.S.M, Shadbolt, T. and Dawe, C. -

Assessment of Natural Resource Condition in and Adjacent to Dry

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Assessment of Natural Resource Condition in and Adjacent to the Dry Tortugas National Park Natural Resource Report NPS/DRTO/NRR—2012/558 ON THE COVER Sergeant majors (Abudefduf saxatilis) in Dry Tortugas National Park. Photograph by NOAA/NOS/NCCOS/CCMA Biogeography Branch Assessment of Natural Resource Conditions In and Adjacent to Dry Tortugas National Park Natural Resource Report NPS/DRTO/NRR—2012/558 Christopher F. G. Jeffrey1,2 ,Sarah D. Hile1,2, Christine Addison3, Jerald S. Ault4, Carolyn Currin3, Don Field3, Nicole Fogarty5, Jiangang Luo4, Vanessa McDonough6, Doug Morrison7, Greg Piniak1, Varis Ransibrahmanakul1, Steve G. Smith4, Shay Viehman3 Editor: Christopher F. G. Jeffrey1,2 1National Oceanic and Atmospheric 4University of Miami Administration Rosenstiel School of Marine and National Ocean Service, National Centers Atmospheric Science for Coastal Ocean Science 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway Center for Coastal Monitoring and Miami, FL 33149-1098 Assessment, Biogeography Branch 1305 East West Highway, SSMC4, N/SCI-1 5Nova Southeastern University Silver Spring, MD 20910 Oceanographic Center 8000 N. Ocean Drive 2Consolidated Safety Services, Inc. Dania Beach, Florida 10301 Democracy Lane, Suite 300 Fairfax, VA 22030 6National Park Service Biscayne National Park 3National Oceanic and Atmospheric 9700 SW 328 Street Administration Homestead, Florida 33033 National Ocean Service, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science 7National Park Service