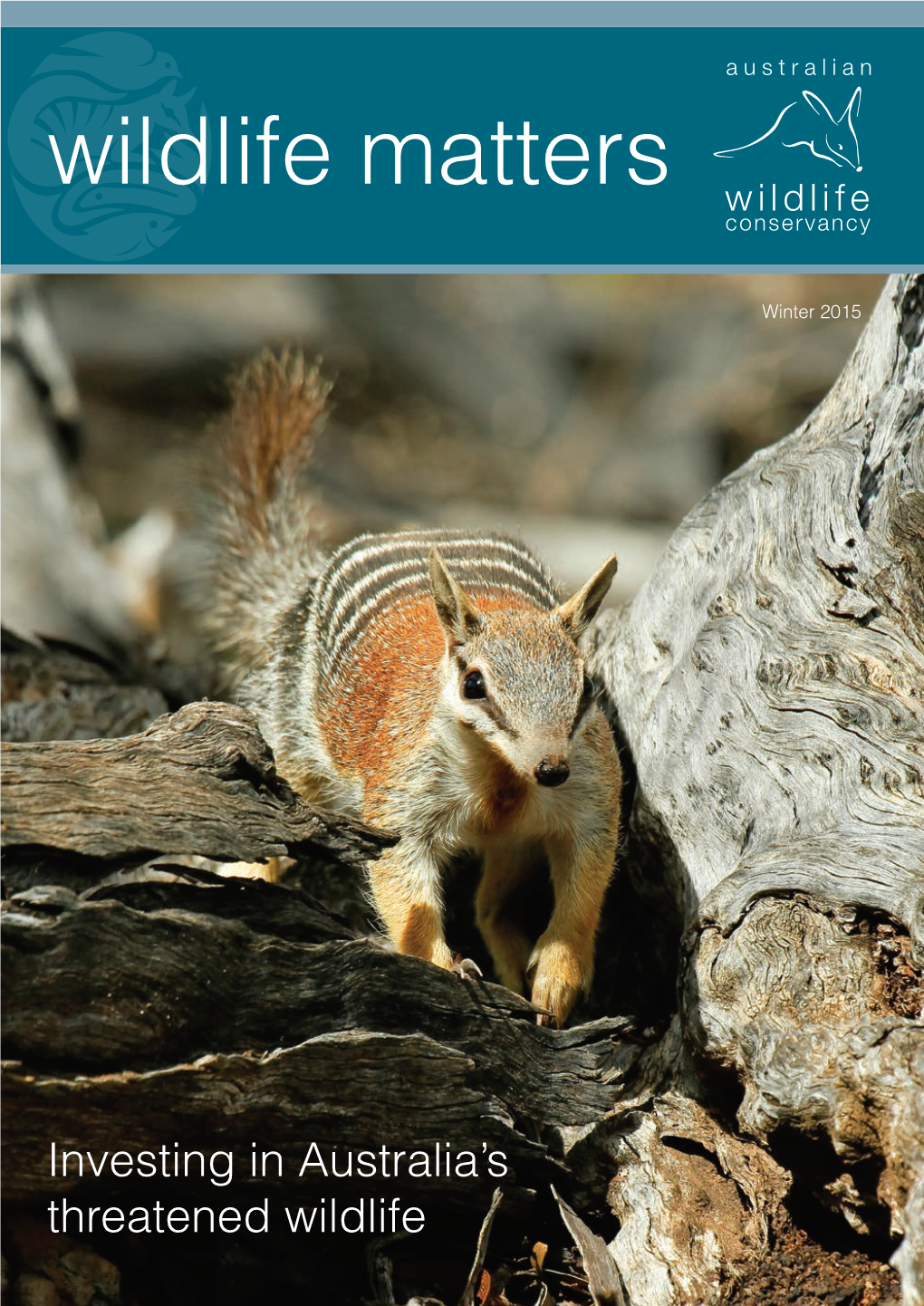

Wildlife Matters: Winter 2015 1 Wildlife Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Felixer™ Grooming Trap Non-Target Safety Trial: Numbats July 2020

Felixer™ Grooming Trap Non-Target Safety Trial: Numbats July 2020 Brian Chambers, Judy Dunlop, Adrian Wayne Summary Felixer™ cat grooming traps are a novel and potential useful means for controlling feral cats that have proven difficult, or very expensive to control by other methods such as baiting, shooting and trapping. The South West Catchments Council (SWCC) and the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) plan to undertake a meso-scale trial of Felixer™ traps in the southern jarrah forest where numbats (Myrmecobius fasciatus) are present. Felixer™ traps have not previously been deployed in areas with numbat populations. We tested the ability of Felixer™ traps to identify numbats as a non-target species by setting the traps in camera only mode in pens with four numbats at Perth Zoo. The Felixer™ traps were triggered 793 times by numbats with all detections classified as non-targets. We conclude that the Felixer™ trap presents no risk to numbats as a non-target species. Acknowledgements We are grateful Peter Mawson, Cathy Lambert, Karen Cavanough, Jessica Morrison and Aimee Moore of Perth Zoo for facilitating access to the numbats for the trial. The trial was approved by the Perth Zoo Animal Ethics Committee (Project No. 2020-4). The Felixer™ traps used in this project were provided by Fortescue Metals Group Pty Ltd and Roy Hill Mining Pty Ltd. This trial was supported by the South West Catchments Council with funding through the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program. ii Felixer™ - Numbat Safety Trial -

Lindsay Masters

CHARACTERISATION OF EXPERIMENTALLY INDUCED AND SPONTANEOUSLY OCCURRING DISEASE WITHIN CAPTIVE BRED DASYURIDS Scott Andrew Lindsay A thesis submitted in fulfillment of requirements for the postgraduate degree of Masters of Veterinary Science Faculty of Veterinary Science University of Sydney March 2014 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY Apart from assistance acknowledged, this thesis represents the unaided work of the author. The text of this thesis contains no material previously published or written unless due reference to this material is made. This work has neither been presented nor is currently being presented for any other degree. Scott Lindsay 30 March 2014. i SUMMARY Neosporosis is a disease of worldwide distribution resulting from infection by the obligate intracellular apicomplexan protozoan parasite Neospora caninum, which is a major cause of infectious bovine abortion and a significant economic burden to the cattle industry. Definitive hosts are canid and an extensive range of identified susceptible intermediate hosts now includes native Australian species. Pilot experiments demonstrated the high disease susceptibility and the unexpected observation of rapid and prolific cyst formation in the fat-tailed dunnart (Sminthopsis crassicaudata) following inoculation with N. caninum. These findings contrast those in the immunocompetent rodent models and have enormous implications for the role of the dunnart as an animal model to study the molecular host-parasite interactions contributing to cyst formation. An immunohistochemical investigation of the dunnart host cellular response to inoculation with N. caninum was undertaken to determine if a detectable alteration contributes to cyst formation, compared with the eutherian models. Selective cell labelling was observed using novel antibodies developed against Tasmanian devil proteins (CD4, CD8, IgG and IgM) as well as appropriate labelling with additional antibodies targeting T cells (CD3), B cells (CD79b, PAX5), granulocytes, and the monocyte-macrophage family (MAC387). -

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Northern Quoll ©

Species Fact Sheet: Northern quoll © V i e w f i n d e r Nothern quoll Dasyurus hallucatus The northern quoll is a medium-sized carnivorous marsupial that lives in the savannas of northern Australia. It is found from south-eastern Queensland all the way to the northern parts of the Western Australian coast. Populations have declined across much of this range, particularly as a result of the spread of the cane toad. Recent translocations to islands in northern Australia free from feral animals have had some success in increasing populations on islands Conservation status The World Conservation Union (IUCN) Redlist of Threatened Species: Lower risk – near threatened Australian Government - Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 : Endangered Did you know? Western Australia. They have been associated with the de - mise of a number of native species. • Although they are marsupials, female northern quolls do not have a pouch. At the start of the Conservation action breeding season the area around the nipples becomes enlarged and partially surrounded by a Communities, scientists and governments are working flap of skin. The young (usually six in a litter) live together to coordinate the research and management here for the first eight to 10 weeks of their lives. effort. The Threatened Species Network, a community- • Almost all male northern quolls die at about one based program of the Australian Government and WWF- year old, not long after mating. Australia, recently provided funding for Traditional Owners to survey Maria Island in the Northern Territory for northern Distribution and habitat quolls. On Groote Eylandt, the most significant island for northern quolls, a TSN Community Grant is providing funds Northern quolls live in a range of habitats but prefer rocky to help quarantine the island from hitch-hiking cane toads areas and eucalypt forests. -

The Hunter and Biodiversity in Tasmania

The Hunter and Biodiversity in Tasmania The Hunter takes place on Tasmania’s Central Plateau, where “One hundred and sixty-five million years ago potent forces had exploded, clashed, pushed the plateau hundreds of metres into the sky.” [a, 14] The story is about the hunt for the last Tasmanian tiger, described in the novel as: “that monster whose fabulous jaw gapes 120 degrees, the carnivorous marsupial which had so confused the early explorers — a ‘striped wolf’, ‘marsupial wolf.’” [a, 16] Fig 1. Paperbark woodlands and button grass plains near Derwent Bridge, Central Tasmania. Source: J. Stadler, 2010. Biodiversity “Biodiversity”, or biological diversity, refers to variety in all forms of life—all plants and animals, their genes, and the ecosystems they live in. [b] It is important because all living things are connected with each other. For example, humans depend on living things in the environment for clean air to breathe, food to eat, and clean water to drink. Biodiversity is one of the underlying themes in The Hunter, a Tasmanian film directed by David Nettheim in 2011 and based on Julia Leigh’s 1999 novel about the hunt for the last Tasmanian Tiger. The film and the novel showcase problems that arise from loss of species, loss of habitat, and contested ideas about land use. The story is set in the Central Plateau Conservation Area and much of the film is shot just south of that area near Derwent Bridge and in the Florentine Valley. In Tasmania, land clearing is widely considered to be the biggest threat to biodiversity [c, d]. -

Feral Cats: Killing 75 Million Native Animals Every Night Saving Australia’S Threatened Wildlife

wildlife matters Summer 2012/13 Feral cats: killing 75 million native animals every night Saving Australia’s threatened wildlife Welcome to the Summer 2012/13 edition of Wildlife Matters. The AWC mission As you will read in the following pages, our focus remains firmly on battling the The mission of Australian Wildlife “ecological axis of evil” – feral animals, wildfires and weeds. For decades, these Conservancy (AWC) is the effective forces have been steadily eroding Australia’s natural capital, causing the extinction conservation of all Australian animal of wildlife and the destruction of habitats and ecological processes. The role of feral species and the habitats in which they live. cats – which kill 75 million native animals every day – is particularly significant. To achieve this mission, our actions are focused on: Our response to this tripartite attack on Australia’s natural capital is straightforward • Establishing a network of sanctuaries – we deliver practical land management informed by world-class science. Central which protect threatened wildlife and to our strategy is the fact that around 80% of our staff are based in the field. AWC’s ecosystems: AWC now manages dedicated team of field operatives – land managers and ecologists – represent the 23 sanctuaries covering over 3 million front-line in our battle against fire, ferals and weeds. Within the conservation sector, hectares (7.4 million acres). we are unique in deploying such a high proportion of our staff in the field. • Implementing practical, on-ground To date, this strategy has delivered significant, measurable and very positive conservation programs to protect ecological returns. This success is particularly apparent when considering the the wildlife at our sanctuaries: these surviving populations of Australia’s most endangered mammals. -

Factsheet: a Threatened Mammal Index for Australia

Science for Saving Species Research findings factsheet Project 3.1 Factsheet: A Threatened Mammal Index for Australia Research in brief How can the index be used? This project is developing a For the first time in Australia, an for threatened plants are currently Threatened Species Index (TSX) for index has been developed that being assembled. Australia which can assist policy- can provide reliable and rigorous These indices will allow Australian makers, conservation managers measures of trends across Australia’s governments, non-government and the public to understand how threatened species, or at least organisations, stakeholders and the some of the population trends a subset of them. In addition to community to better understand across Australia’s threatened communicating overall trends, the and report on which groups of species are changing over time. It indices can be interrogated and the threatened species are in decline by will inform policy and investment data downloaded via a web-app to bringing together monitoring data. decisions, and enable coherent allow trends for different taxonomic It will potentially enable us to better and transparent reporting on groups or regions to be explored relative changes in threatened understand the performance of and compared. So far, the index has species numbers at national, state high-level strategies and the return been populated with data for some and regional levels. Australia’s on investment in threatened species TSX is based on the Living Planet threatened and near-threatened birds recovery, and inform our priorities Index (www.livingplanetindex.org), and mammals, and monitoring data for investment. a method developed by World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological A Threatened Species Index for mammals in Australia Society of London. -

Ba3444 MAMMAL BOOKLET FINAL.Indd

Intot Obliv i The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia Compiled by James Fitzsimons Sarah Legge Barry Traill John Woinarski Into Oblivion? The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia 1 SUMMARY Since European settlement, the deepest loss of Australian biodiversity has been the spate of extinctions of endemic mammals. Historically, these losses occurred mostly in inland and in temperate parts of the country, and largely between 1890 and 1950. A new wave of extinctions is now threatening Australian mammals, this time in northern Australia. Many mammal species are in sharp decline across the north, even in extensive natural areas managed primarily for conservation. The main evidence of this decline comes consistently from two contrasting sources: robust scientifi c monitoring programs and more broad-scale Indigenous knowledge. The main drivers of the mammal decline in northern Australia include inappropriate fi re regimes (too much fi re) and predation by feral cats. Cane Toads are also implicated, particularly to the recent catastrophic decline of the Northern Quoll. Furthermore, some impacts are due to vegetation changes associated with the pastoral industry. Disease could also be a factor, but to date there is little evidence for or against it. Based on current trends, many native mammals will become extinct in northern Australia in the next 10-20 years, and even the largest and most iconic national parks in northern Australia will lose native mammal species. This problem needs to be solved. The fi rst step towards a solution is to recognise the problem, and this publication seeks to alert the Australian community and decision makers to this urgent issue. -

Environmental Guidance for Planning and Development

Part A Environmental protection and land use planning in Western Australia Environmental Guidance for Part B Biophysical factors Planning and Development Part C Pollution management May 2008 Part D Social surroundings Guidance Statement No. 33 2007389-0508-50 Foreword The Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) is an independent statutory authority and is the key provider of independent environmental advice to Government. The EPA’s objectives are to protect the environment and to prevent, control and abate pollution and environmental harm. The EPA aims to achieve some of this through the development of environmental protection guidance statements for the environmental impact assessment (EIA) of proposals. This document is one in a series being issued by the EPA to assist proponents, consultants and the public generally to gain additional information about the EPA’s thinking in relation to aspects of the EIA process. The series provides the basis for EPA’s evaluation of, and advice on, proposals under S38 and S48A of the Environmental Protection Act 1986 (EP Act) subject to EIA. The guidance statements are one part of assisting proponents, decision-making authorities and others in achieving environmentally acceptable outcomes. Consistent with the notion of continuous environmental improvement and adaptive environmental management, the EPA expects proponents to take all reasonable and practicable measures to protect the environment and to view the requirements of this Guidance as representing the minimum standards necessary. The main purposes of this EPA guidance statement are: • to provide information and advice to assist participants in land use planning and development processes to protect, conserve and enhance the environment • to describe the processes the EPA may apply under the EP Act to land use planning and development in Western Australia, and in particular to describe the environmental impact assessment (EIA) process applied by the EPA to schemes. -

Phylogenetic Relationships of Dasyuromorphian Marsupials Revisited

Whittier College Poet Commons Biology Faculty Publications & Research 2016 Phylogenetic relationships of dasyuromorphian marsupials revisited Christopher A. Emerling Michael Westerman Carey Krajewski Benjamin P. Kear Lucy Meehan See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://poetcommons.whittier.edu/bio Part of the Biology Commons Authors Christopher A. Emerling, Michael Westerman, Carey Krajewski, Benjamin P. Kear, Lucy Meehan, Robert W. Meredith, and Mark S. Springer Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2016, 176, 686–701. With 11 figures. Phylogenetic relationships of dasyuromorphian marsupials revisited 1 2 3 MICHAEL WESTERMAN *, CAREY KRAJEWSKI , BENJAMIN P. KEAR , Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article/176/3/686/2453844 by Whittier College user on 25 September 2020 LUCY MEEHAN1, ROBERT W. MEREDITH4, CHRISTOPHER A. EMERLING4 and MARK S. SPRINGER4 1Genetics Department, LaTrobe University, Melbourne, Vic. 3086, Australia 2Zoology Department, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA 3Paleobiology Programme, Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Villavagen 16, SE-752 36 Uppsala, Sweden 4Department of Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA Received 14 January 2015; revised 30 June 2015; accepted for publication 9 July 2015 We reassessed the phylogenetic relationships of dasyuromorphians using a large molecular database comprising previously published and new sequences for both nuclear (nDNA) and mitochondrial (mtDNA) genes from the numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus), most living species of Dasyuridae, and the recently extinct marsupial wolf, Thylacinus cynocephalus. Our molecular tree suggests that Thylacinidae is sister to Myrmecobiidae + Dasyuridae. We show robust support for the dasyurid intrafamilial classification proposed by Krajewski & Westerman as well as for placement of most dasyurid genera, which suggests substantial homoplasy amongst craniodental characters pres- ently used to generate morphology-based taxonomies. -

ANSWER KEY for the MAMMAL SEARCH and FIND

ANSWER KEY: MAMMAL SEARCH AND FIND A) An animal you already know about B) An animal you have never heard of C) An animal whose name starts with the same letter as your name. (You may use the full species name, the general name, or the scientific name for example: Sloth Bear [Ursus ursinus] is okay for the letters S, B and U.) There are multiple answers for many letters, but here is one for each. A anteater B bongo C coati D dibatag E echidna F fanaloka G giraffe H hedgehog I Indian pangolin J jumping mouse K kultarr L llama M mongoose N numbat O okapi P panda Q quoll katytanis.com #AMisclassificationOfMammals © Katy Tanis 2018 ANSWER KEY: MAMMAL SEARCH AND FIND R raccoon S sloth T tamandua U Ursus ursinus (sloth bear) V vicuna W wildebeest X Xenarthran* Y yellow footed rock wallaby Z zorilla *this is a bit of a cheat Xenarthra is the superorder that include anteaters, tree sloths and armadillo. There were 6 in the show. D) 7 spotted animals African civet fanaloka quoll king cheetah common genet giraffe spotted cuscus E) 2 flying animals Chapin's free-tailed bat Bismarck masked flying fox F) 2 swimming animals Southern Right Whale Commerson's Dolphin katytanis.com #AMisclassificationOfMammals © Katy Tanis 2018 ANSWER KEY: MAMMAL SEARCH AND FIND katytanis.com #AMisclassificationOfMammals © Katy Tanis 2018 ANSWER KEY: MAMMAL SEARCH AND FIND G) 2 mammals that lay eggs short beaked echidna western long beaked echidna H) 2 animals that look similar to skunks and are also stinky long fingered trick Zorilla I) 1 animal that smells like buttered -

The Collapse of Northern Mammal Populations 2 Australian

australian wildlife matters wildlife conservancy Winter 2010 The collapse of northern mammal populations 2 australian saving australia’s threatened wildlife wildlife Pictograph conservancy Welcome to our Winter 2010 edition of Wildlife Matters. I am writing this editorial from our bushcamp at Pungalina-Seven Emu, in the Gulf of Carpentaria. Our biological survey has just commenced and already some exciting discoveries have been made. the awc mission Overnight our fi eld ecologists captured a Carpentarian Pseudantechinus, one of Australia’s rarest mammals. This is only the 21st time that this species has ever been The mission of Australian Wildlife Conservancy recorded (the 20th record was also on Pungalina – see the Spring 2009 edition of (AWC) is the effective conservation of all Wildlife Matters). We have watched rare Ghost Bats, Australia’s only carnivorous bats, Australian animal species and the habitats in emerging from a maternity cave; a mother Dugong, with her calf, resting in the lower which they live. To achieve this mission, our reaches of the Calvert River; Bandicoots digging around Pungalina’s network of lush, actions are focused on: permanent springs; and graceful Antilopine Wallaroos bounding across Pungalina’s • Establishing a network of sanctuaries tropical savannas. which protect threatened wildlife and Pungalina-Seven Emu is a property of immense conservation signifi cance. Yet it ecosystems: AWC now manages lies at the centre – geographically – of an unfolding ecological drama which surely 21 sanctuaries covering over 2.5 million demands our attention: from Cape York to the Kimberley, Australia’s small mammals hectares (6.2 million acres). are disappearing. Species such as the Golden Bandicoot, the Brush-tailed Rabbit-rat • Implementing practical, on-ground and the Northern Quoll have suffered catastrophic declines, disappearing from large conservation programs to protect areas including places as famous and well resourced as Kakadu National Park.