Water Sharing in the Volta Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feed the Future Ghana Agriculture and Natural Resources Management Project Annual Progress Report Fiscal Year 2017 | October 1, 2016 to December 31, 2016

Feed the Future Ghana Agriculture and Natural Resources Management Project Annual Progress Report Fiscal Year 2017 | October 1, 2016 to December 31, 2016 Agreement Number: AID-641-A-16-00010 Submission Date: January 31, 2017 Submitted to: Gloria Odoom, Agreement Officer’s Representative Submitted by: Julie Fischer, Chief of Party Winrock International 2101 Riverfront Drive, Little Rock, Arkansas, USA Tel: +1 501 280 3000 Email: [email protected] DISCLAIMER The report was made possible through the generous support of the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under the Feed the Future initiative. The contents are the responsibility of Winrock International and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. FtF Ghana AgNRM Quarterly Progress Report (FY 2017|Quarter 1) i ACTIVITY/MECHANISM Overview Activity/Mechanism Feed the Future Ghana Agriculture and Natural Resource Name: Management Activity/Mechanism Start Date and End May 2, 2016 – April 30, 2021 Date: Name of Prime Implementing Partner: Winrock International Agreement Number: AID-641-A-16-00010 Names of Sub- TechnoServe, Nature Conservation Research Centre, awardees: Center for Conflict Transformation and Peace Studies Government of Ghana | Ministry of Food and Agriculture Major Counterpart and Forestry Commission Organizations Geographic Coverage Upper East, Upper West and Northern Regions, Ghana, (States/Provinces and West Africa Countries) Reporting Period: October 1, 2016 – December 31, 2016 FtF Ghana AgNRM Quarterly Progress Report (FY 2017|Quarter 1) ii Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................................................................. iv 1. ACTIVITY IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS ............................................... 1 1.1 Progress Narrative & Implementation Status..................................................................... 2 1.2 Implementation Challenges ................................................................................................... -

The Volt a Resettlement Experience

The Volt a Resettlement Experience edited, by ROBERT CHAMBERS PALL MALL PRESS LONDON in association with Volta River Authority University of Science and Technology Accra Kumasi INSTITUTI OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES LIBRARY Published by the Pall Mall Press Ltd 5 Cromwell Place, London swj FIRST PUBLISHED 1970 © Pall Mall Press, 1970 SBN 269 02597 9 Printed in Great Britain by Western Printing Services Ltd Bristol I CONTENTS PREFACE Xlll FOREWORD I SIR ROBERT JACKSON I. INTRODUCTION IO ROBERT CHAMBERS The Preparatory Commission Policy: Self-Help with Incentives, 12 Precedents, Pressures and Delays, 1956-62, 17 Formulating a New Policy, 1961-63, 24 2. THE ORGANISATION OF RESETTLEMENT 34 E. A. K. KALITSI Organisation and Staffing, 35 Evolution of Policy, 39 Housing and compensation policy, 39; Agricultural policy, 41; Regional planning policy, 42 Execution, 44 Demarcation, 44; Valuation, 45; Social survey, 46; Site selection, 49; Clearing and construction, 52; Evacuation, 53; Farming, 55 Costs and Achievements, 56 3. VALUATION, ACQUISITION AND COMPENSATION FOR PURPOSES OF RESETTLEMENT 58 K. AMANFO SAGOE Scope and Scale of the Exercise, 59 Public and Private Rights Affected, 61 Ethical and Legal Bases for the Government's Compensation Policies, 64 Valuation and Compensation for Land, Crops and Buildings, 67 Proposals for Policy in Resettlements, 72 Conclusion, 75 v CONTENTS 4. THE SOCIAL SURVEY 78 D. A. P. BUTCHER Purposes and Preparation, 78 Executing the Survey, 80 Processing and Analysis of Data, 82 Immediate Usefulness, 83 Future Uses for the Survey Data, 86 Social Aspects of Housing and the New Towns, 88 Conclusion, 90 5. SOCIAL WELFARE IO3 G. -

Volta-Hycos Project

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANISATION Weather • Climate • Water VOLTA-HYCOS PROJECT SUB-COMPONENT OF THE AOC-HYCOS PROJECT PROJECT DOCUMENT SEPTEMBER 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………………………….v 1 WORLD HYDROLOGICAL CYCLE OBSERVING SYSTEM (WHYCOS)……………1 2. BACKGROUNG TO DEVELOPMENT OF VOLTA-HYCOS…………………………... 3 2.1 AOC-HYCOS PILOT PROJECT............................................................................................... 3 2.2 OBJECTIVES OF AOC HYCOS PROJECT ................................................................................ 3 2.2.1 General objective........................................................................................................................ 3 2.2.2 Immediate objectives .................................................................................................................. 3 2.3 LESSONS LEARNT IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AOC-HYCOS BASED ON LARGE BASINS......... 4 3. THE VOLTA BASIN FRAMEWORK……………………………………………………... 7 3.1 GEOGRAPHICAL ASPECTS....................................................................................................... 7 3.2 COUNTRIES OF THE VOLTA BASIN ......................................................................................... 8 3.3 RAINFALL............................................................................................................................. 10 3.4 POPULATION DISTRIBUTION IN THE VOLTA BASIN.............................................................. 11 3.5 SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS........................................................................................... -

Water Resources and Environmental Management in Ghana

Journal of the Faculty of Environmental Science and Technology, Okayama University Vo1.9, No.I. pp.87-98. February 2004 Water Resources and Environmental Management in Ghana Kwabena KANKAM-YEBOAH*, Philip GYAU-BOAKYE**, Makoto NISHIGAKI*** and Mitsuru KOMATSU*** (Received December 3, 2003) Three principal river basins are found in Ghana and the Volta River Basin is the major one, covering about three-quarters of Ghana. The basin is shared with Mali, Burkina Faso, Cote d'lvoire, Togo and Benin. Water from the Volta River Basin is used for drinking water supply, generating hydro-electric power, irrigation, inland fisheries and lake transport. The sustainable management of the Volta River Basin is thus of great importance. Land use activities in the basin are thus closely monitored not only in Ghana, but also in the other riparian countries as well. This paper presents information and data on the water resources and environmental management of the Volta River Basin in Ghana. Key words: water resources, environmental management, Volta River Basin, Ghana, water utilization 1 INTRODUCTION both the forest and savannah zones since the early 1970s (Opoku-Ankomah and Amisigo, 1998; Paturel, et al. Ghana is covered by three main river basins. These 1997; Aka, et al. 1996). The mean annual temperatures are the Volta, South-Western and the Coastal Basins. The vary between 24.4 DC and 28.1 DC. Gyau-Boakye and Volta River Basin (Fig. 1) covers about 70 % of the total Tumbulto (2000) have observed that the mean annual surface area of the country and it is shared by six West temperature in the basin has increased by 1 DC between Africa countries, namely; Ghana, Mali, Burkina Faso, 1945 and 1993. -

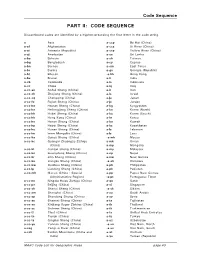

Code Sequence

Code Sequence PART II: CODE SEQUENCE Discontinued codes are identified by a hyphen preceding the first letter in the code string. a Asia a-ccp Bo Hai (China) a-af Afghanistan a-ccs Xi River (China) a-ai Armenia (Republic) a-ccy Yellow River (China) a-aj Azerbaijan a-ce Sri Lanka a-ba Bahrain a-ch Taiwan a-bg Bangladesh a-cy Cyprus a-bn Borneo a-em East Timor a-br Burma a-gs Georgia (Republic) a-bt Bhutan -a-hk Hong Kong a-bx Brunei a-ii India a-cb Cambodia a-io Indonesia a-cc China a-iq Iraq a-cc-an Anhui Sheng (China) a-ir Iran a-cc-ch Zhejiang Sheng (China) a-is Israel a-cc-cq Chongqing (China) a-ja Japan a-cc-fu Fujian Sheng (China) a-jo Jordan a-cc-ha Hainan Sheng (China) a-kg Kyrgyzstan a-cc-he Heilongjiang Sheng (China) a-kn Korea (North) a-cc-hh Hubei Sheng (China) a-ko Korea (South) a-cc-hk Hong Kong (China) a-kr Korea a-cc-ho Henan Sheng (China) a-ku Kuwait a-cc-hp Hebei Sheng (China) a-kz Kazakhstan a-cc-hu Hunan Sheng (China) a-le Lebanon a-cc-im Inner Mongolia (China) a-ls Laos a-cc-ka Gansu Sheng (China) -a-mh Macao a-cc-kc Guangxi Zhuangzu Zizhiqu a-mk Oman (China) a-mp Mongolia a-cc-ki Jiangxi Sheng (China) a-my Malaysia a-cc-kn Guangdong Sheng (China) a-np Nepal a-cc-kr Jilin Sheng (China) a-nw New Guinea a-cc-ku Jiangsu Sheng (China) -a-ok Okinawa a-cc-kw Guizhou Sheng (China) a-ph Philippines a-cc-lp Liaoning Sheng (China) a-pk Pakistan a-cc-mh Macao (China : Special a-pp Papua New Guinea Administrative Region) -a-pt Portuguese Timor a-cc-nn Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu (China) a-qa Qatar a-cc-pe Beijing (China) a-si Singapore -

The Volta River Basin

The Volta River Basin An assessment of groundwater need by Martin Jäger & Sven Menge Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe (BGR) April 2012 Page 1 Page 2 Acronyms AGW-net African Groundwater Network AMCOW African Ministerial Conference on Water BAF Burkina Faso BGR Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe CIDA Canadian International Development Agency CT Continental Terminal DANIDA Danish International Development Agency GEF Global Environmental Fund GIS Geographic Information System GLOWA Global Water Cycle GW Groundwater GWP Global Water Partnership GWRM Groundwater Resources Management HQ Headquarter IRD Institut de Recherche et Dévéloppement IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature IWRM Integrated Water Resources Management L/RBO Lake/River Basin Organization L/R/ABO Lake/River Association of Basin Organizations MC Member Country Mamsl above mean sea level Mgt Management NBA Niger Basin Authority NE North East NFP National Focal Point NGO Non-Governmental Organization VOLTA-HYCOS Volta Hydrological Cycle Observation System NW North West SE South East SIDA Swedish International Development Agency SP Strategic Plan SW South West SWOT Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats TBA Transboundary Aquifer UNDP United Nations Development Program UNEP United Nations Environmental Program VBA Volta Basin Authority WRM Water Resources Management Page 3 Contents Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................ -

Open Whole.Kad.Final3re.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Earth and Mineral Sciences MANAGING WATER RESOURCES UNDER CLIMATE VARIABILITY AND CHANGE: PERSPECTIVES OF COMMUNITIES IN THE AFRAM PLAINS, GHANA A Thesis in Geography by Kathleen Ann Dietrich © 2008 Kathleen Ann Dietrich Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2008 The thesis of Kathleen Ann Dietrich was reviewed and approved* by the following: Petra Tschakert Assistant Professor of Geography Alliance for Earth Sciences, Engineering, and Development in Africa Thesis Adviser C. Gregory Knight Professor of Geography Karl Zimmerer Professor of Geography Head of the Department of Geography *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Climate variability and change alter the amount and timing of water resources available for rural communities in the Afram Plains district, Ghana. Given the fact that the district has been experiencing a historical and multi-scalar economic and political neglect, its communities face a particular vulnerability for accessing current and future water resources. Therefore, these communities must adapt their water management strategies to both future climate change and the socio-economic context. Using participatory methods and interviews, I explore the success of past and present water management strategies by three communities in the Afram Plains in order to establish potentially effective responses to future climate change. Currently, few strategies are linked to climate variability and change; however, the methods and results assist in giving voice to the participant communities by recognizing, sharing, and validating their experiences of multiple climatic and non-climatic vulnerabilities and the past, current, and future strategies which may enhance their adaptive capacity. -

![Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014 [FR307]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8869/ghana-demographic-and-health-survey-2014-fr307-1888869.webp)

Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014 [FR307]

Ghana 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey Demographic and Health Survey 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014 Ghana Statistical Service Accra, Ghana Ghana Health Service Accra, Ghana The DHS Program ICF International Rockville, Maryland, USA October 2015 International Labour Organization This report summarises the findings of the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (2014 GDHS), implemented by the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), the Ghana Health Service (GHS), and the National Public Health Reference Laboratory (NPHRL) of the GHS. Financial support for the survey was provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria through the Ghana AIDS Commission (GAC) and the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), and the Government of Ghana. ICF International provided technical assistance through The DHS Program, a USAID-funded project offering support and technical assistance in the implementation of population and health surveys in countries worldwide. Additional information about the 2014 GDHS may be obtained from the Ghana Statistical Service, Head Office, P.O. Box GP 1098, Accra, Ghana; Telephone: 233-302-682-661/233-302-663-578; Fax: 233-302-664-301; E-mail: [email protected]. Information about The DHS Program may be obtained from ICF International, 530 Gaither Road, Suite 500, Rockville, MD 20850, USA; Telephone: +1-301-407-6500; Fax: +1-301-407-6501; E-mail: [email protected]; Internet: www.DHSprogram.com. -

Impact of Climate Change and Variability on Hydropower in Ghana

Impact of Climate Change and Variability on Hydropower in Ghana. Sylvester Afram Boadi1* & Kwadwo Owusu2 1Climate Change & Sustainable Development Programme, University of Ghana, P.O. Box LG 59, Legon. Accra, Ghana. Telephone Number: 0245726816. Institutional E-mail: [email protected] 2Climate Change & Sustainable Development Programme, University of Ghana, P.O. Box LG 59, Legon. Accra, Ghana. Telephone Number: 0279943213. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Abstract Ghana continues to rely heavily on hydropower for her electricity needs. This hydropower reliance cannot ensure sustainable development since there is a strong association between hydropower production and climate variability and change including ENSO related lake water levels reduction. Using regression analysis this study found that rainfall variability accounted for 21% of the inter- annual fluctuations in power generation from the Akosombo Hydroelectric power station between 1970 and 1990 while ENSO and lake water level accounted for 72.4% of the inter-annual fluctuations between 1991 and 2010. There is therefore the need to diversify power production to attain energy security in Ghana. Keywords: climate change and variability; El Niño-Southern Oscillation; hydropower; energy security; Ghana. 2 Background The impacts of climate variability and change are real and would continue to affect sensitive sectors of the global economy. Productive sectors such as agriculture, water, health, energy and transport among others bear the brunt of these variability and change in the world’s climate (IPCC, 2007). The reliance on climate sensitive sectors such as hydropower has become a challenge to sustainable development as a result of climate variability and change impacts on power generation (Okudzeto, Mariki, Paepe & Sedegah, 2014). -

Ghana Water Resources Profile Overview Ghana Has Abundant Water Resources and Is Not Considered Water Stressed Overall

WATER RESOURCES PROFILE SERIES The Water Resources Profile Series synthesizes information on water resources, water quality, the water-related dimen- sions of climate change, and water governance and provides an overview of the most critical water resources challenges and stress factors within USAID Water for the World Act High Priority Countries. The profile includes: a summary of avail- able surface and groundwater resources; analysis of surface and groundwater availability and quality challenges related to water and land use practices; discussion of climate change risks; and synthesis of governance issues affecting water resources management institutions and service providers. Ghana Water Resources Profile Overview Ghana has abundant water resources and is not considered water stressed overall. The total volume of freshwater withdrawn by major economic sectors amounts to 6.3 percent of its total resource endowment, which is lower than the water stress benchmark.i Total renewable water resources per person of 1,949 m3 is also above the Falkenmark Indexii threshold for water stress. However, water availability is influenced by management decisions and abstractions from upper-basin countries as almost half of its freshwater originates outside the country. The Volta Basin covers most of the country and is critical to hydroelectric generation, agriculture, and fisheries. However, water availability for hydropower generation and agriculture is vulnerable to drought and depends on upper basin dam releases and abstractions in Burkina Faso. Flood risks are amplified by uncoordinated floodgate releases from upstream dams. Transboundary cooperation is needed to reconcile basin development plans and address flood mitigation and drought contingencies in the Volta Basin. Informal gold mining, logging, and the expanding cocoa sector are increasing flood risks, erosion, and sedimentation in the Southwestern and Coastal Basins. -

Aquaculture-Mediated Invasion of the Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (Gift) Into the Lower Volta Basin of Ghana

Article Aquaculture-Mediated Invasion of the Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (Gift) into the Lower Volta Basin of Ghana Gifty Anane-Taabeah 1,2, Emmanuel A. Frimpong 2,* and Eric Hallerman 2 1 Department of Fisheries and Watershed Management, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, PMB, University Post Office, Kumasi, Ghana; [email protected] 2 Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, 24061, USA; [email protected] (E.A.F.); [email protected] (E.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +15-402-316-880 Received: 18 July 2019; Accepted: 30 September 2019; Published: 2 October 2019 Abstract: The need for improved aquaculture productivity has led to widespread pressure to introduce the Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (GIFT) strains of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) into Africa. However, the physical and regulatory infrastructures for preventing the escape of farmed stocks into wild populations and ecosystems are generally lacking. This study characterized the genetic background of O. niloticus being farmed in Ghana and assessed the genetic effects of aquaculture on wild populations. We characterized O. niloticus collected in 2017 using mitochondrial and microsatellite DNA markers from 140 farmed individuals sampled from five major aquaculture facilities on the Volta Lake, and from 72 individuals sampled from the wild in the Lower Volta River downstream of the lake and the Black Volta tributary upstream of the lake. Our results revealed that two farms were culturing non-native O. niloticus stocks, which were distinct from the native Akosombo strain. The non-native tilapia stocks were identical to several GIFT strains, some of which showed introgression of mitochondrial DNA from non-native Oreochromis mossambicus. -

Ghana) with Special Reference to the Burrowing Mayfly Povilla Adusta Navas By

Hydrobiologia vol. 36, 3-4, p . 373-398, 1970 . Macroinvertebrates of Flooded Trees in the Man-Made Volta Lake (Ghana) with Special Reference to the Burrowing Mayfly Povilla adusta Navas by T. PETR* Volta Basin Research Project and Department of Zoology, Uni- versity of Ghana, Legon INTRODUCTION During the lacustrinization of the Man-made Volta Lake in Ghana, periphyton has steadily increased in importance as a food source for aquatic animals . Flooded trees have provided a suitable substrate for periphyton in the epilimnion of the inshore and off- shore areas, the land not having been cleared before the Lake was formed . The biomass of periphyton has greatly exceeded that of benthos (PETR, 1969a) since even in relatively shallow water a deoxygenated water layer has frequently developed at the bottom and prevented the formation of benthos . Investigation of the food of the most important commercial fish species of the Volta Lake showed that during 1965 and 1966, i .e. one to two years after the Akosombo dam was closed, periphyton did not form a very significant part of fish diet (LAWSON et al., 1969) . The indirect importance of periphyton was however great as it provided food and shelter for aquatic invertebrates . Some of these invertebrates became extremely abundant and their im- portance as fish food gradually increased. TERMINOLOGY The animals considered in the present paper inhabit the surfaces of flooded trees, covered by periphyton, and burrow into the substrate itself. *Present address : Department of Zoology, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda . Received September 5th, 1969 . 373 The most adequate terms for such organisms seem to be those suggested by SRAMEK-HUSEK (1946) and SLADECKOVA (1962) who describe them as attached and dependent organisms .