The Volt a Resettlement Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Dayi District

SOUTH DAYI DISTRICT i Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the South Dayi District is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Volta Region

VOLTA REGION AGRICULTURAL CLASS NO NAME CURRENT GRADE RCC/MMDA QUALIFICATION INSTITUTION REMARKS ATTENDED Akatsi South District University of Cape Upgrading 1 Josephine Ekua Hope Production Officer Assembly BSc. Agricultural Extention Coast Akatsi South District University of Upgrading 2 Micheal Kofi Alorzuke Senior Technical Officer Assembly BSc. Agricultural Science Edu. Education Evangelical Upgrading Hohoe Municipal Presbyterian 3 Bernard Bredzei Senior Technical Officer Assembly BSc. Agribusiness University College Assistant Chief Anloga District BSc. Agricultural eXtension and University of Cape Upgrading 4 Agnes Gakpetor Technical Officer Assembly Community Development Coast Kpando Muncipal Bach. Of Techno. In Agric. Upgrading 5 Francis Mawunya Fiti Technician Engineer Assembly Engineering KNUST Lydia Asembmitaka Ketu Municipal University of Cape Upgrading 6 Akum Sub Proffessional Assembly BSc. Agricultural Extention Coast ENGINEERING CLASS NO NAME CURRENT GRADE RCC/MMDA QUALIFICATION INSTITUTION REMARKS ATTENDED Senior Technician Adaklu District BSc. Construction Technology Upgrading 1 Edmund Mawutor Engineer Assembly and Manage. KNUST Senior Technician Agotime-Ziope BSc. Quantity Surveying and Upgrading 2 John Kwaku Asamany Engineer District Assembly Construction Economics KNUST Eddison-Mark Senior Technician Ho Municipal BSc. Construction Technology Upgrading 3 Bodjawah Engineer Assembly and Management KNUST Senior Technician Akatsi North District BSc. Construction Technology Upgrading 4 Felix Tetteh Ametepee Engineer Assembly and Management KNUST 1 TECHNICIAN ENGINEER NO NAME CURRENT GRADE RCC/MMDA QUALIFICATION INSTITUTION REMARKS ATTENDED Abadza Christian Hohoe Municipal Kpando Technical Upgrading 1 Mensah Senior Technical Officer Assembly Technician Part III Institute PROCUREMENT CLASS NO NAME CURRENT GRADE RCC/MMDA QUALIFICATION INSTITUTION REMARKS ATTENDED Higher Executive North Dayi District BSc. Logistics and Supply Chain Conversion 1 Catherine Deynu Officer Assembly Management KNUST Allassan Mohammed BSc. -

Alcohol Consumption Among Tertiary Students in the Hohoe Municipality

Aboagye et al. BMC Psychiatry (2021) 21:431 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03447-0 RESEARCH Open Access Alcohol consumption among tertiary students in the Hohoe municipality, Ghana: analysis of prevalence, effects, and associated factors from a cross-sectional study Richard Gyan Aboagye1*, Nuworza Kugbey2, Bright Opoku Ahinkorah3, Abdul-Aziz Seidu4, Abdul Cadri5 and Paa Yeboah Akonor1 Abstract Background: Alcohol consumption constitutes a major public health problem as it has negative consequences on the health, social, psychological, and economic outcomes of individuals. Tertiary education presents students with unique challenges and some students resort to the use of alcohol in dealing with their problems. This study, therefore, sought to determine alcohol use, its effects, and associated factors among tertiary students in the Hohoe Municipaility of Ghana. Methods: An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 418 tertiary students in the Hohoe Municipality of Ghana using a two-stage sampling technique. Data were collected using structured questionnaires. A binary logistic regression modelling was used to determine the strength of the association between alcohol consumption and the explanatory variables. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Stata version 16.0 was used to perform the analysis. Results: The lifetime prevalence of alcohol consumption was 39.5%. Out of them, 49.1% were still using alcohol, translating to an overall prevalence of 19.4% among the tertiary students. Self-reported perceived effects attributed to alcohol consumption were loss of valuable items (60.6%), excessive vomiting (53.9%), stomach pains/upset (46.1%), accident (40.0%), unprotected sex (35.1%), risk of liver infection (16.4%), depressive feelings (27.3%), diarrhoea (24.2%), debt (15.2%), and petty theft (22.4%). -

Volta-Hycos Project

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANISATION Weather • Climate • Water VOLTA-HYCOS PROJECT SUB-COMPONENT OF THE AOC-HYCOS PROJECT PROJECT DOCUMENT SEPTEMBER 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………………………….v 1 WORLD HYDROLOGICAL CYCLE OBSERVING SYSTEM (WHYCOS)……………1 2. BACKGROUNG TO DEVELOPMENT OF VOLTA-HYCOS…………………………... 3 2.1 AOC-HYCOS PILOT PROJECT............................................................................................... 3 2.2 OBJECTIVES OF AOC HYCOS PROJECT ................................................................................ 3 2.2.1 General objective........................................................................................................................ 3 2.2.2 Immediate objectives .................................................................................................................. 3 2.3 LESSONS LEARNT IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AOC-HYCOS BASED ON LARGE BASINS......... 4 3. THE VOLTA BASIN FRAMEWORK……………………………………………………... 7 3.1 GEOGRAPHICAL ASPECTS....................................................................................................... 7 3.2 COUNTRIES OF THE VOLTA BASIN ......................................................................................... 8 3.3 RAINFALL............................................................................................................................. 10 3.4 POPULATION DISTRIBUTION IN THE VOLTA BASIN.............................................................. 11 3.5 SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS........................................................................................... -

FINAL REPORT for 2017 & 2018 Mining SECTOR

REPUBLIC OF GHANA MINISTRY OF FINANCE GHANA EXTRACTIVE INDUSTRIES TRANSPARENCY INITIATIVE (GHEITI) FINAL REPORT FOR 2017 & 2018 MINING SECTOR DECEMBER, 2019 GHEITI SECRETARIAT TEL: +233(0)302 686101 EXT 6318 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gheiti.gov.gh Table of Contents List of Abbreviations............................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary................................................................................................................ 6 1.0 Introduction...................................................................................................................21 1.2 Overview of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (ASM)............................... 23 1.2.1 ASM in Ghana....................................................................................................23 1.2.2 Licencing Regime for ASM............................................................................24 1.2.3 ASM Product Marketing................................................................................. 25 1.2.4 Recent Developments....................................................................................25 2.0 Legal and Institutional Framework, including allocation of contracts and Licences.....................................................................................................................................27 2.1. Fiscal Regime.......................................................................................................... -

Ghana Poverty Mapping Report

ii Copyright © 2015 Ghana Statistical Service iii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Ghana Statistical Service wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the Government of Ghana, the UK Department for International Development (UK-DFID) and the World Bank through the provision of both technical and financial support towards the successful implementation of the Poverty Mapping Project using the Small Area Estimation Method. The Service also acknowledges the invaluable contributions of Dhiraj Sharma, Vasco Molini and Nobuo Yoshida (all consultants from the World Bank), Baah Wadieh, Anthony Amuzu, Sylvester Gyamfi, Abena Osei-Akoto, Jacqueline Anum, Samilia Mintah, Yaw Misefa, Appiah Kusi-Boateng, Anthony Krakah, Rosalind Quartey, Francis Bright Mensah, Omar Seidu, Ernest Enyan, Augusta Okantey and Hanna Frempong Konadu, all of the Statistical Service who worked tirelessly with the consultants to produce this report under the overall guidance and supervision of Dr. Philomena Nyarko, the Government Statistician. Dr. Philomena Nyarko Government Statistician iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ -

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana Small and medium forest enterprises (SMFEs) serve as the main or additional source of income for more than three million Ghanaians and can be broadly categorised into wood forest products, non-wood forest products and forest services. Many of these SMFEs are informal, untaxed and largely invisible within state forest planning and management. Pressure on the forest resource within Ghana is growing, due to both domestic and international demand for forest products and services. The need to improve the sustainability and livelihood contribution of SMFEs has become a policy priority, both in the search for a legal timber export trade within the Voluntary Small and Medium Partnership Agreement (VPA) linked to the European Union Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (EU FLEGT) Action Plan, and in the quest to develop a national Forest Enterprises strategy for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD). This sourcebook aims to shed new light on the multiple SMFE sub-sectors that in Ghana operate within Ghana and the challenges they face. Chapter one presents some characteristics of SMFEs in Ghana. Chapter two presents information on what goes into establishing a small business and the obligations for small businesses and Ghana Government’s initiatives on small enterprises. Chapter three presents profiles of the key SMFE subsectors in Ghana including: akpeteshie (local gin), bamboo and rattan household goods, black pepper, bushmeat, chainsaw lumber, charcoal, chewsticks, cola, community-based ecotourism, essential oils, ginger, honey, medicinal products, mortar and pestles, mushrooms, shea butter, snails, tertiary wood processing and wood carving. -

Volta Region

REGIONAL ANALYTICAL REPORT VOLTA REGION Ghana Statistical Service June, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ghana Statistical Service Prepared by: Martin K. Yeboah Augusta Okantey Emmanuel Nii Okang Tawiah Edited by: N.N.N. Nsowah-Nuamah Chief Editor: Nii Bentsi-Enchill ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There cannot be any meaningful developmental activity without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, and socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. The Kilimanjaro Programme of Action on Population adopted by African countries in 1984 stressed the need for population to be considered as a key factor in the formulation of development strategies and plans. A population census is the most important source of data on the population in a country. It provides information on the size, composition, growth and distribution of the population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of resources, government services and the allocation of government funds among various regions and districts for education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users with an analytical report on the 2010 PHC at the regional level to facilitate planning and decision-making. This follows the publication of the National Analytical Report in May, 2013 which contained information on the 2010 PHC at the national level with regional comparisons. Conclusions and recommendations from these reports are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence-based policy formulation, planning, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programs. -

Name Phone Number Location Certification Class 1 Abayah Joseph Tetteh 0244814202 Somanya, Krobo,Eastern Region Domestic 2 Abdall

NAME PHONE NUMBER LOCATION CERTIFICATION CLASS 1 ABAYAH JOSEPH TETTEH 0244814202 SOMANYA, KROBO,EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 2 ABDALLAH MOHAMMED 0246837670 KANTUDU, EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 3 ABLORH SOWAH EMMANUEL 0209114424 AKIM-ODA, EASTERN COMMERCIAL 4 ABOAGYE ‘DANKWA BENJAMIN 0243045450 AKUAPIM DOMESTIC 5 ABURAM JEHOSAPHAT 0540594543 AKIM AYIREDI,EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 6 ACHEAMPONG BISMARK 0266814518 SORODAE, EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 7 ACHEAMPONG ERNEST 0209294941 KOFORIDUA, EASTERN REGION COMMERCIAL 8 ACHEAMPONG ERNEST KWABENA 0208589610 KOFORIDUA, EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 9 ACHEAMPONG KOFI 0208321461 AKIM ODA,EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 10 ACHEAMPONG OFORI CHARLES 0247578581 OYOKO,KOFORIDUA, EASTERN REGIO COMMERCIAL 11 ADAMS LUKEMAN 0243005800 KWAHDESCO BUS STOP DOMESTIC 12 ADAMU FRANCIS 0207423555 ADOAGYIRI-NKAWKAW, EASTERN REG DOMESTIC 13 ADANE PETER 0546664481 KOFORIDUA,EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 14 ADDO-TETEBO KWAME 0208166017 SODIE, KOFORIDUA INDUSTRIAL 15 ADJEI SAMUEL OFORI 0243872431/0204425237 KOFORIDUA COMMERCIAL 16 ADONGO ROBERT ATOA 0244525155/0209209330 AKIM ODA COMMERCIAL 17 ADONGO ROBERT ATOA 0244525155 AKIM,ODA,EASTERN REGIONS INDUSTRIAL 18 ADRI WINFRED KWABLA 0246638316 AKOSOMBO COMMERCIAL 19 ADU BROBBEY 0202017110 AKOSOMBO,E/R DOMESTIC 20 ADU HENAKU WILLIAM KOFORIDUA DOMESTIC 21 ADUAMAH SAMPSON ODAME 0246343753 SUHUM, EASTERN REGION DOMESTIC 22 ADU-GYAMFI FREDERICK 0243247891/0207752885 AKIM ODA COMMERCIAL 23 AFFUL ABEDNEGO 0245805682 ODA AYIREBI COMMERCIAL 24 AFFUL KWABENA RICHARD 0242634300 MARKET NKWATIA DOMESTIC 25 AFFUL -

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: the Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6"

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: The Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6", By Paul Christopher Nugent A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. October 1991 ProQuest Number: 10672604 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672604 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This is a study of the processes through which the former Togoland Trust Territory has come to constitute an integral part of modern Ghana. As the section of the country that was most recently appended, the territory has often seemed the most likely candidate for the eruption of separatist tendencies. The comparative weakness of such tendencies, in spite of economic crisis and governmental failure, deserves closer examination. This study adopts an approach which is local in focus (the area being Likpe), but one which endeavours at every stage to link the analysis to unfolding processes at the Regional and national levels. -

GUINEA WORM WRAP-UP #141 To

Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES and Prevention (CDC) Memorandum Date: March 22, 2004 From: WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis Subject: GUINEA WORM WRAP-UP #141 To: Addressees Are you and Your Program Detecting All Cases Within 24 Hours? What Proportion of Your Cases Were Detected Within 24 Hours Last Month? Nigeria Guinea Worm Eradication Program Number of Cases Number of Cases Number of Cases Admitted to Reported Contained CCC within 24 hours Jan. 2004 101 81 45 Feb. 2004 73 64 43 Total 174 145 88 % Contained within 24 hours 83% 51% INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION RECOMMENDS CERTIFICATION OF 17 MORE COUNTRIES, INCLUDING SENEGAL AND YEMEN The World Health Organization convened the Fifth Meeting of the International Commission for the Certification of Dracunculiasis Eradication (ICCDE) at WHO headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland on March 9-11, 2004. This was the first meeting of the Commission since February 2000. After thorough review of materials submitted, including reports of International Certification Teams in some instances, the Commission recommended that Senegal and Yemen of the recently endemic countries be certified as now free of dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease). Senegal and Yemen detected their last indigenous cases of the disease in 1997. Senegal thus becomes the first of the recently-endemic African countries, and Yemen the last of the recently-endemic Asian countries (India and Pakistan are the others) to be recommended for certification by the Commission. The Commission also recommended that the director-general of WHO certify the following 15 countries: “Cape Verde, Comoros, Congo Brazzaville, Equatorial Guinea, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Israel, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Madagascar, Mauritius, Palestine (West-Bank and Gaza strip), Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Serbia-Montenegro, and Uruguay”. -

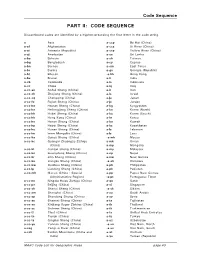

Code Sequence

Code Sequence PART II: CODE SEQUENCE Discontinued codes are identified by a hyphen preceding the first letter in the code string. a Asia a-ccp Bo Hai (China) a-af Afghanistan a-ccs Xi River (China) a-ai Armenia (Republic) a-ccy Yellow River (China) a-aj Azerbaijan a-ce Sri Lanka a-ba Bahrain a-ch Taiwan a-bg Bangladesh a-cy Cyprus a-bn Borneo a-em East Timor a-br Burma a-gs Georgia (Republic) a-bt Bhutan -a-hk Hong Kong a-bx Brunei a-ii India a-cb Cambodia a-io Indonesia a-cc China a-iq Iraq a-cc-an Anhui Sheng (China) a-ir Iran a-cc-ch Zhejiang Sheng (China) a-is Israel a-cc-cq Chongqing (China) a-ja Japan a-cc-fu Fujian Sheng (China) a-jo Jordan a-cc-ha Hainan Sheng (China) a-kg Kyrgyzstan a-cc-he Heilongjiang Sheng (China) a-kn Korea (North) a-cc-hh Hubei Sheng (China) a-ko Korea (South) a-cc-hk Hong Kong (China) a-kr Korea a-cc-ho Henan Sheng (China) a-ku Kuwait a-cc-hp Hebei Sheng (China) a-kz Kazakhstan a-cc-hu Hunan Sheng (China) a-le Lebanon a-cc-im Inner Mongolia (China) a-ls Laos a-cc-ka Gansu Sheng (China) -a-mh Macao a-cc-kc Guangxi Zhuangzu Zizhiqu a-mk Oman (China) a-mp Mongolia a-cc-ki Jiangxi Sheng (China) a-my Malaysia a-cc-kn Guangdong Sheng (China) a-np Nepal a-cc-kr Jilin Sheng (China) a-nw New Guinea a-cc-ku Jiangsu Sheng (China) -a-ok Okinawa a-cc-kw Guizhou Sheng (China) a-ph Philippines a-cc-lp Liaoning Sheng (China) a-pk Pakistan a-cc-mh Macao (China : Special a-pp Papua New Guinea Administrative Region) -a-pt Portuguese Timor a-cc-nn Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu (China) a-qa Qatar a-cc-pe Beijing (China) a-si Singapore