23 Hyperbolic Geometry §

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Manifolds

Examples of Manifolds Example 1 (Open Subset of IRn) Any open subset, O, of IRn is a manifold of dimension n. One possible atlas is A = (O, ϕid) , where ϕid is the identity map. That is, ϕid(x) = x. n Of course one possible choice of O is IR itself. Example 2 (The Circle) The circle S1 = (x,y) ∈ IR2 x2 + y2 = 1 is a manifold of dimension one. One possible atlas is A = {(U , ϕ ), (U , ϕ )} where 1 1 1 2 1 y U1 = S \{(−1, 0)} ϕ1(x,y) = arctan x with − π < ϕ1(x,y) <π ϕ1 1 y U2 = S \{(1, 0)} ϕ2(x,y) = arctan x with 0 < ϕ2(x,y) < 2π U1 n n n+1 2 2 Example 3 (S ) The n–sphere S = x =(x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ IR x1 +···+xn+1 =1 n A U , ϕ , V ,ψ i n is a manifold of dimension . One possible atlas is 1 = ( i i) ( i i) 1 ≤ ≤ +1 where, for each 1 ≤ i ≤ n + 1, n Ui = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi > 0 ϕi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n Vi = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi < 0 ψi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n So both ϕi and ψi project onto IR , viewed as the hyperplane xi = 0. Another possible atlas is n n A2 = S \{(0, ··· , 0, 1)}, ϕ , S \{(0, ··· , 0, −1)},ψ where 2x1 2xn ϕ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1−xn+1 1−xn+1 2x1 2xn ψ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1+xn+1 1+xn+1 are the stereographic projections from the north and south poles, respectively. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

The Sphere Project

;OL :WOLYL 7YVQLJ[ +XPDQLWDULDQ&KDUWHUDQG0LQLPXP 6WDQGDUGVLQ+XPDQLWDULDQ5HVSRQVH ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[ 7KHULJKWWROLIHZLWKGLJQLW\ ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[PZHUPUP[PH[P]L[VKL[LYTPULHUK WYVTV[LZ[HUKHYKZI`^OPJO[OLNSVIHSJVTT\UP[` /\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY YLZWVUKZ[V[OLWSPNO[VMWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ /\THUP[HYPHU >P[O[OPZ/HUKIVVR:WOLYLPZ^VYRPUNMVYH^VYSKPU^OPJO [OLYPNO[VMHSSWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ[VYLLZ[HISPZO[OLPY *OHY[LYHUK SP]LZHUKSP]LSPOVVKZPZYLJVNUPZLKHUKHJ[LK\WVUPU^H`Z[OH[ YLZWLJ[[OLPY]VPJLHUKWYVTV[L[OLPYKPNUP[`HUKZLJ\YP[` 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZ This Handbook contains: PU/\THUP[HYPHU (/\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY!SLNHSHUKTVYHSWYPUJPWSLZ^OPJO HUK YLÅLJ[[OLYPNO[ZVMKPZHZ[LYHMMLJ[LKWVW\SH[PVUZ 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZPU/\THUP[HYPHU9LZWVUZL 9LZWVUZL 7YV[LJ[PVU7YPUJPWSLZ *VYL:[HUKHYKZHUKTPUPT\TZ[HUKHYKZPUMV\YRL`SPMLZH]PUN O\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYZ!>H[LYZ\WWS`ZHUP[H[PVUHUKO`NPLUL WYVTV[PVU"-VVKZLJ\YP[`HUKU\[YP[PVU":OLS[LYZL[[SLTLU[HUK UVUMVVKP[LTZ"/LHS[OHJ[PVU;OL`KLZJYPILwhat needs to be achieved in a humanitarian response in order for disaster- affected populations to survive and recover in stable conditions and with dignity. ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVRLUQV`ZIYVHKV^ULYZOPWI`HNLUJPLZHUK PUKP]PK\HSZVMMLYPUN[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYH common language for working together towards quality and accountability in disaster and conflict situations ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVROHZHU\TILYVMºJVTWHUPVU Z[HUKHYKZ»L_[LUKPUNP[ZZJVWLPUYLZWVUZL[VULLKZ[OH[ OH]LLTLYNLK^P[OPU[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VY ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[^HZPUP[PH[LKPU I`HU\TILY VMO\THUP[HYPHU5.6ZHUK[OL9LK*YVZZHUK 9LK*YLZJLU[4V]LTLU[ ,+0;065 7KHB6SKHUHB3URMHFWBFRYHUBHQBLQGG The Sphere Project Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response Published by: The Sphere Project Copyright@The Sphere Project 2011 Email: [email protected] Website : www.sphereproject.org The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response: the Sphere Handbook. -

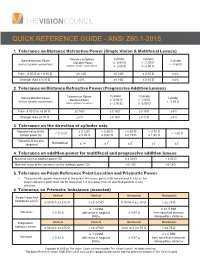

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

Einstein's Velocity Addition Law and Its Hyperbolic Geometry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Computers and Mathematics with Applications 53 (2007) 1228–1250 www.elsevier.com/locate/camwa Einstein’s velocity addition law and its hyperbolic geometry Abraham A. Ungar∗ Department of Mathematics, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58105, USA Received 6 March 2006; accepted 19 May 2006 Abstract Following a brief review of the history of the link between Einstein’s velocity addition law of special relativity and the hyperbolic geometry of Bolyai and Lobachevski, we employ the binary operation of Einstein’s velocity addition to introduce into hyperbolic geometry the concepts of vectors, angles and trigonometry. In full analogy with Euclidean geometry, we show in this article that the introduction of these concepts into hyperbolic geometry leads to hyperbolic vector spaces. The latter, in turn, form the setting for hyperbolic geometry just as vector spaces form the setting for Euclidean geometry. c 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Special relativity; Einstein’s velocity addition law; Thomas precession; Hyperbolic geometry; Hyperbolic trigonometry 1. Introduction The hyperbolic law of cosines is nearly a century old result that has sprung from the soil of Einstein’s velocity addition law that Einstein introduced in his 1905 paper [1,2] that founded the special theory of relativity. It was established by Sommerfeld (1868–1951) in 1909 [3] in terms of hyperbolic trigonometric functions as a consequence of Einstein’s velocity addition of relativistically admissible velocities. Soon after, Varicakˇ (1865–1942) established in 1912 [4] the interpretation of Sommerfeld’s consequence in the hyperbolic geometry of Bolyai and Lobachevski. -

Old-Fashioned Relativity & Relativistic Space-Time Coordinates

Relativistic Coordinates-Classic Approach 4.A.1 Appendix 4.A Relativistic Space-time Coordinates The nature of space-time coordinate transformation will be described here using a fictional spaceship traveling at half the speed of light past two lighthouses. In Fig. 4.A.1 the ship is just passing the Main Lighthouse as it blinks in response to a signal from the North lighthouse located at one light second (about 186,000 miles or EXACTLY 299,792,458 meters) above Main. (Such exactitude is the result of 1970-80 work by Ken Evenson's lab at NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology in Boulder) and adopted by International Standards Committee in 1984.) Now the speed of light c is a constant by civil law as well as physical law! This came about because time and frequency measurement became so much more precise than distance measurement that it was decided to define the meter in terms of c. Fig. 4.A.1 Ship passing Main Lighthouse as it blinks at t=0. This arrangement is a simplified model for a 1Hz laser resonator. The two lighthouses use each other to maintain a strict one-second time period between blinks. And, strict it must be to do relativistic timing. (Even stricter than NIST is the universal agency BIGANN or Bureau of Intergalactic Aids to Navigation at Night.) The simulations shown here are done using RelativIt. Relativistic Coordinates-Classic Approach 4.A.2 Fig. 4.A.2 Main and North Lighthouses blink each other at precisely t=1. At p recisel y t=1 sec. -

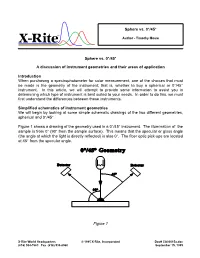

Sphere Vs. 0°/45° a Discussion of Instrument Geometries And

Sphere vs. 0°/45° ® Author - Timothy Mouw Sphere vs. 0°/45° A discussion of instrument geometries and their areas of application Introduction When purchasing a spectrophotometer for color measurement, one of the choices that must be made is the geometry of the instrument; that is, whether to buy a spherical or 0°/45° instrument. In this article, we will attempt to provide some information to assist you in determining which type of instrument is best suited to your needs. In order to do this, we must first understand the differences between these instruments. Simplified schematics of instrument geometries We will begin by looking at some simple schematic drawings of the two different geometries, spherical and 0°/45°. Figure 1 shows a drawing of the geometry used in a 0°/45° instrument. The illumination of the sample is from 0° (90° from the sample surface). This means that the specular or gloss angle (the angle at which the light is directly reflected) is also 0°. The fiber optic pick-ups are located at 45° from the specular angle. Figure 1 X-Rite World Headquarters © 1995 X-Rite, Incorporated Doc# CA00015a.doc (616) 534-7663 Fax (616) 534-8960 September 15, 1995 Figure 2 shows a drawing of the geometry used in an 8° diffuse sphere instrument. The sphere wall is lined with a highly reflective white substance and the light source is located on the rear of the sphere wall. A baffle prevents the light source from directly illuminating the sample, thus providing diffuse illumination. The sample is viewed at 8° from perpendicular which means that the specular or gloss angle is also 8° from perpendicular. -

Hyperbolic Trigonometry in Two-Dimensional Space-Time Geometry

Hyperbolic trigonometry in two-dimensional space-time geometry F. Catoni, R. Cannata, V. Catoni, P. Zampetti ENEA; Centro Ricerche Casaccia; Via Anguillarese, 301; 00060 S.Maria di Galeria; Roma; Italy January 22, 2003 Summary.- By analogy with complex numbers, a system of hyperbolic numbers can be intro- duced in the same way: z = x + hy; h2 = 1 x, y R . As complex numbers are linked to the { ∈ } Euclidean geometry, so this system of numbers is linked to the pseudo-Euclidean plane geometry (space-time geometry). In this paper we will show how this system of numbers allows, by means of a Cartesian representa- tion, an operative definition of hyperbolic functions using the invariance respect to special relativity Lorentz group. From this definition, by using elementary mathematics and an Euclidean approach, it is straightforward to formalise the pseudo-Euclidean trigonometry in the Cartesian plane with the same coherence as the Euclidean trigonometry. PACS 03 30 - Special Relativity PACS 02.20. Hj - Classical groups and Geometries 1 Introduction Complex numbers are strictly related to the Euclidean geometry: indeed their invariant (the module) arXiv:math-ph/0508011v1 3 Aug 2005 is the same as the Pythagoric distance (Euclidean invariant) and their unimodular multiplicative group is the Euclidean rotation group. It is well known that these properties allow to use complex numbers for representing plane vectors. In the same way hyperbolic numbers, an extension of complex numbers [1, 2] defined as z = x + hy; h2 =1 x, y R , { ∈ } are strictly related to space-time geometry [2, 3, 4]. Indeed their square module given by1 z 2 = 2 2 | | zz˜ x y is the Lorentz invariant of two dimensional special relativity, and their unimodular multiplicative≡ − group is the special relativity Lorentz group [2]. -

Recognizing Surfaces

RECOGNIZING SURFACES Ivo Nikolov and Alexandru I. Suciu Mathematics Department College of Arts and Sciences Northeastern University Abstract The subject of this poster is the interplay between the topology and the combinatorics of surfaces. The main problem of Topology is to classify spaces up to continuous deformations, known as homeomorphisms. Under certain conditions, topological invariants that capture qualitative and quantitative properties of spaces lead to the enumeration of homeomorphism types. Surfaces are some of the simplest, yet most interesting topological objects. The poster focuses on the main topological invariants of two-dimensional manifolds—orientability, number of boundary components, genus, and Euler characteristic—and how these invariants solve the classification problem for compact surfaces. The poster introduces a Java applet that was written in Fall, 1998 as a class project for a Topology I course. It implements an algorithm that determines the homeomorphism type of a closed surface from a combinatorial description as a polygon with edges identified in pairs. The input for the applet is a string of integers, encoding the edge identifications. The output of the applet consists of three topological invariants that completely classify the resulting surface. Topology of Surfaces Topology is the abstraction of certain geometrical ideas, such as continuity and closeness. Roughly speaking, topol- ogy is the exploration of manifolds, and of the properties that remain invariant under continuous, invertible transforma- tions, known as homeomorphisms. The basic problem is to classify manifolds according to homeomorphism type. In higher dimensions, this is an impossible task, but, in low di- mensions, it can be done. Surfaces are some of the simplest, yet most interesting topological objects. -

Hyperbolic Geometry

Flavors of Geometry MSRI Publications Volume 31,1997 Hyperbolic Geometry JAMES W. CANNON, WILLIAM J. FLOYD, RICHARD KENYON, AND WALTER R. PARRY Contents 1. Introduction 59 2. The Origins of Hyperbolic Geometry 60 3. Why Call it Hyperbolic Geometry? 63 4. Understanding the One-Dimensional Case 65 5. Generalizing to Higher Dimensions 67 6. Rudiments of Riemannian Geometry 68 7. Five Models of Hyperbolic Space 69 8. Stereographic Projection 72 9. Geodesics 77 10. Isometries and Distances in the Hyperboloid Model 80 11. The Space at Infinity 84 12. The Geometric Classification of Isometries 84 13. Curious Facts about Hyperbolic Space 86 14. The Sixth Model 95 15. Why Study Hyperbolic Geometry? 98 16. When Does a Manifold Have a Hyperbolic Structure? 103 17. How to Get Analytic Coordinates at Infinity? 106 References 108 Index 110 1. Introduction Hyperbolic geometry was created in the first half of the nineteenth century in the midst of attempts to understand Euclid’s axiomatic basis for geometry. It is one type of non-Euclidean geometry, that is, a geometry that discards one of Euclid’s axioms. Einstein and Minkowski found in non-Euclidean geometry a This work was supported in part by The Geometry Center, University of Minnesota, an STC funded by NSF, DOE, and Minnesota Technology, Inc., by the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, and by NSF research grants. 59 60 J. W. CANNON, W. J. FLOYD, R. KENYON, AND W. R. PARRY geometric basis for the understanding of physical time and space. In the early part of the twentieth century every serious student of mathematics and physics studied non-Euclidean geometry. -

Using Differentials to Differentiate Trigonometric and Exponential Functions Tevian Dray

Using Differentials to Differentiate Trigonometric and Exponential Functions Tevian Dray Tevian Dray ([email protected]) received his B.S. in mathematics from MIT in 1976, his Ph.D. in mathematics from Berkeley in 1981, spent several years as a physics postdoc, and is now a professor of mathematics at Oregon State University. A Fellow of the American Physical Society for his early work in general relativity, his current research interests include the octonions as well as science education. He directs the Vector Calculus Bridge Project. (http://www.math.oregonstate.edu/bridge) Differentiating a polynomial is easy. To differentiate u2 with respect to u, start by computing d.u2/ D .u C du/2 − u2 D 2u du C du2; and then dropping the last term, an operation that can be justified in terms of limits. Differential notation, in general, can be regarded as a shorthand for a formal limit argument. Still more informally, one can argue that du is small compared to u, so that the last term can be ignored at the level of approximation needed. After dropping du2 and dividing by du, one obtains the derivative, namely d.u2/=du D 2u. Even if one regards this process as merely a heuristic procedure, it is a good one, as it always gives the correct answer for a polynomial. (Physicists are particularly good at knowing what approximations are appropriate in a given physical context. A physicist might describe du as being much smaller than the scale imposed by the physical situation, but not so small that quantum mechanics matters.) However, this procedure does not suffice for trigonometric functions. -

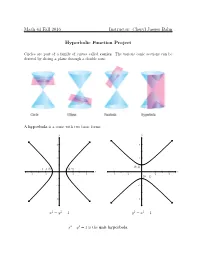

Cheryl Jaeger Balm Hyperbolic Function Project

Math 43 Fall 2016 Instructor: Cheryl Jaeger Balm Hyperbolic Function Project Circles are part of a family of curves called conics. The various conic sections can be derived by slicing a plane through a double cone. A hyperbola is a conic with two basic forms: y y 4 4 2 2 • (0; 1) (−1; 0) (1; 0) • • x x -4 -2 2 4 -4 -2 2 4 (0; −1) • -2 -2 -4 -4 x2 − y2 = 1 y2 − x2 = 1 x2 − y2 = 1 is the unit hyperbola. Hyperbolic Functions: Similar to how the trigonometric functions, cosine and sine, correspond to the x and y values of the unit circle (x2 + y2 = 1), there are hyperbolic functions, hyperbolic cosine (cosh) and hyperbolic sine (sinh), which correspond to the x and y values of the right side of the unit hyperbola (x2 − y2 = 1). y y -1 1 x x π π 3π 2π π π 3π 2π 2 2 2 2 -1 -1 cos x sin x y y 6 2 4 x 2 -2 2 • (0; 1) -2 x -2 2 cosh x sinh x Hyperbolic Angle: Just like how the argument for the trigonometric functions is an angle, the argument for the hyperbolic functions is something called a hyperbolic angle. Instead of being defined by arc length, the hyperbolic angle is defined by area. If that seems confusing, consider the area of the circular sector of the unit circle. The r2θ equation for the area of a circular sector is Area = 2 , so because the radius of the unit circle is 1, any sector of the unit circle will have an area equal to half of the sector's central θ angle, A = 2 .