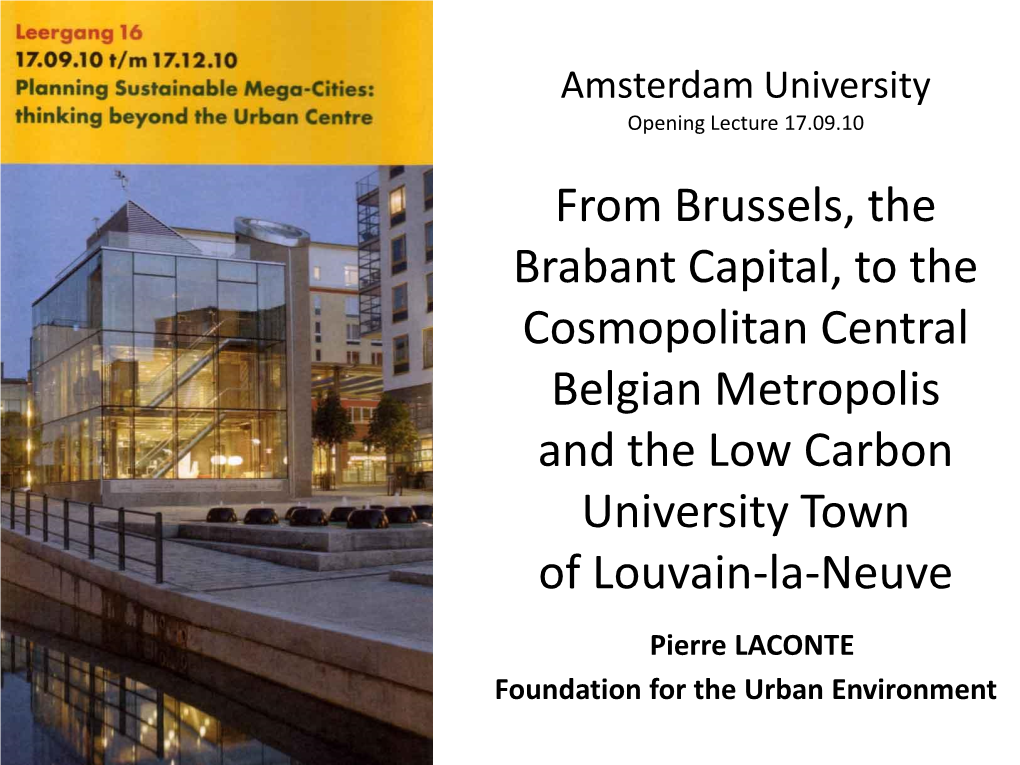

A Low Carbon Town in Mega City Brussels: the Open Central Belgian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welcome to LONDON TOWN SQUARE

Welcome to LONDON TOWN SQUARE 3545 - 32nd Avenue NE, Calgary,AB Partnership. Performance. Josh Rahme | 403.232.4333 Hani Abdelkader | 403.232.4321 Morena Ianniello | 587.293.3367 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] © 2017, Avison Young Real Estate Alberta Inc. All rights reserved. The information contained herein was obtained from sources which we deem reliable and, while thought to be correct, is not guaranteed by Avison Young. LONDON TOWN SQUARE RETAIL SPACE FOR LEASE 3545 - 32 Avenue NE, Calgary,AB Particulars Highlights UNIT SIZE (SF) OCCUPANCY - 120,304 sf community shopping centre located 205 1,521 Nov 1, 2018 in the northeast quadrant of Calgary 210 544 Immediately - Strong tenant mix, including London Drugs, TD 225 1,482 July 1, 2018 Canada Trust, Starbucks, Penningtons, and Liquor 235 1,318 May 1, 2018 Depot 239 944 Nov 1, 2018 555 1,200 Immediately - Located at the southwest corner of 32nd Avenue and 36th Street NE Rental rates: Market - Exposure to 44,000 vehicles per day along 36th Street NE CAM: $7.84 psf (2018 est.) LONDON TOWN SQUARE - Shadow anchored by Sunridge Mall, the largest 32 AVENUE NE AND 36 STREET NE | 3431Tax: – 3545 32 AVENUE$6.09 NE, psf CALGARY, (2018 est.) AB mall in northeast Calgary (+850,000 GLA) Zoning: C - C2 KEYPLAN CONCEPTUALTerm: PLAN ONLY 5 - 10 years BARLOW AVAILABLE TRAIL NE WHITEHORN DRIVE NE 32 AVENUE NE 32 Avenue32 AVENUE NE NE (27,000 vpd) 36 STREET NE 26 AVENUE NE TOTAL SITE AREA 10.37 ACRES 1,200 SF TOTAL SITE GLA 120,307 sf TOTAL PARKING 595 SPACES 500 PARKING RATIO 4.95/1,000 555 505 TENANTS 610 605 603 553 510 100 LONDON DRUGS 24,081 sf 205 PHO HA VIENTNAMESE NOODLE 1,521 sf (44,000 vpd) 210 LEASING OPPORTUNITY 546 sf 1,482 SF 215 PENNINGTON’S STORAGE 531 SF 544 SF 220 DR. -

Town Square Park Master Plan Public Hearing Draft

TOWN SQUARE PARK MASTER PLAN PUBLIC HEARING DRAFT MAY 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Municipality of Anchorage Parks and Recreation Department and the planning team would like to recognize and thank all the individuals and organizations who have worked to create the Town Square Park Master Plan. A special thanks to the members of the Citizen and Technical Advisory Groups for their dedication, insight and assistance. MUNICIPALITY OF CITIZEN ADVISORY ANCHORAGE GROUP MEMBERS PHOTO CREDITS Ethan Berkowitz, Mayor Radhika Krishna Bettisworth North, Erik Jones: cover, contents, 1, 7, 9, 21, 22, 23, 25-26, 28, 30, 33, 37, 42, Chris Schutte, Director of Economic and Shannon Kuhn Community Development 49, 55, 57, 59, 60, 65, 77-78, 78, 85, 87 Dianne Holmes John Rodda, Director of Parks & Recreation Tayna Iden P&R Horticulture Department: 59, 83 Josh Durand, Parks Superintendent Nancy Harbour James Starzec MOA Parks and Recreation, Steve Rafuse: 3, Nina Bonito Romine 4, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14, 17-18, 23 24, 27, 28, 30, PLANNING TEAM Jennifer Richcreek 32, 33, 35, 41, 45, 53, 58, 60, 61-62, 65-66, John Blaine 66, 68, 69, 75, 77, 83, 89, 95, 100 MOA PARKS & RECREATION Darrel Hess Steve Rafuse, Project Manager R&M Consultants, Van Le: 34 BETTISWORTH NORTH TECHNICAL ADVISORS Anchorage Downtown Partnership: 5-6, 17, Mark Kimerer, Landscape Architect 43-44, 57, 79-80, 81-82 Erik Jones, Landscape Designer GROUP MEMBERS R&M CONSULTANTS Jamie Boring Van Le, Planner Elise Huggins Taryn Oleson, Planner Erin Baca Katie Chan, Graphic Designer Sandy Potvin Sharon Chamard -

Lautenschlagerstraße 23, Stuttgart, Germany

Lautenschlagerstraße 23, Stuttgart, Germany View this office online at: https://www.newofficeeurope.com/details/serviced-offices-lautenschlagerstra- e-23-stuttgart This business centre, located at Lautenschlagerstraße 23, Stuttgart, offers modern office accommodation which is available on highly flexible agreements. Rental periods can range from just a day to a month or more, making this a very attractive prospect for those who do not require a long term business commitment. Multilingual staff are on hand to provide a manned reception, mail handling and management support. The property includes meeting rooms, comfortable lounge, 24/7 access and secure parking. Transport links Nearest tube: Schloßplatz/Friedrichsbau Nearest railway station: Stattgart Nearest road: Schloßplatz/Friedrichsbau Nearest airport: Schloßplatz/Friedrichsbau Key features 24 hour access Access to multiple centres nation-wide Board room Caterer services available Close to railway station Comfortable lounge Conference rooms Flexible contracts Lift Meeting rooms Modern interiors Multilingual staff Near to subway / underground station On-site management support Postal facilities/mail handling Reception staff Secure car parking Training rooms available Unbranded offices Unfurnished Virtual office available WC (separate male & female) Location This business centre is located within just a few minutes’ walk of Stuttgart’s largest and most popular town square, Schloßplatz. From here you can easily access the wonderful shopping street of Königstraße – said to be the country’s longest pedestrianised street. The popular Königsbau Passagen shopping mall is also just minutes from the business centre. The local area includes numerous bars, cafés and restaurants and a great variety of other attractions including a number of museums, several parks and two castles. -

Main-Street-Antique-Guide.Pdf

71277_antique guide.qxd 4/1/14 8:37 AM Page 1 Outside the Main Street promenade from 5. The original “Goldie’s Window” and wine storage cabinets; the unique sideboard Fremont Street This outstanding example of Victorian stained glass niche includes panels which depict characters and 1. The Blackhawk • Private Car 92, artistry originally graced Ms. Goldie Schiesser’s home in morals of Aesop’s Fables. the Private Rail Car used by St. Joseph, Missouri. Goldie refused to sell the window, 12. The Louisa Alcott uide Buffalo Bill. until finally an art dealer from Aspen, Colorado agreed This Pullman parlor car was Buffalo Bill Cody used this car to travel to buy the entire home. This is the original window built by the Pullman Company which was later reproduced by stained glass artist Mark to with his Wild West Show from 1906 until his in 1927, and was one in a death in 1917. Bogenrief. His replicas are located at several locations series of cars named for The car was built in 1903 by the Pullman throughout Main Street Station. women authors and poets. Palace Car Company, as the private car for 6. Fluted Columns from the Windsor Barracks. The car has been refurbished the president of the Chicago, Burlington & These cast iron columns originally supported the to provide an elegant cigar- Quincy Railroad. The interior contains a sitting room Barracks which housed the Army guards of the British Throne smoking lounge. with sleeping berths, a dining room, kitchen, and a in London, England. 13. Chandeliers from the Coca-Cola Building, bathroom with showers. -

A Student's Guide to Study Abroad in Brussels

A STUDENT’S GUIDE TO STUDY ABROAD IN BRUSSELS Prepared by the Center for Global Education CONTENTS Section 1: Nuts and Bolts 1.1 Contact Information & Emergency Contact Information 1.2 Program Participant List 1.3 Term Calendar 1.4 Passport & Visas 1.5 Power of Attorney/Medical Release 1.6 International Student Identity Card 1.7 Register to Vote 1.8 Travel Dates/Group Arrival 1.9 Orientation 1.10 What to Bring Section 2: Studying & Living Abroad 2.1 Academics Abroad 2.2 Money and Banking 2.3 Housing and Meals Abroad 2.4 Service Abroad 2.5 Email Access 2.6 Travel Tips Section 3: All About Culture 3.1 Experiential Learning: What it’s all about 3.2 Adjusting to a New Culture 3.3 Culture Learning: Customs and Values Section 4: Health and Safety 4.1 Safety Abroad: A Framework 4.2 Health Care and Insurance 4.3 Women’s Issues Abroad 4.4 HIV 4.5 Drugs 4.6 Traffic 4.7 Politics 4.8 Voting by Absentee Ballot Section 5: Coming Back 5.1 Registration & Housing 5.2 Reentry and Readjustment SECTION 1: Nuts and Bolts 1.1 CONTACT INFORMATION PROGRAM DIRECTOR IN BRUSSELS Dr. Virginie Goffaux Study Abroad Director Vesalius College Mailing address: Pleinlaan 2 1050 Brussels, Belgium Visiting Address: Triomflaan 32 1160 Brussels, Belgium Email: [email protected] Tel: +32 2 629 28 26 Cell: + 32 496 10 97 51 Fax: +32 2 880 12 51 24/7 Emergency cell phone: +32 473 881 221 CONTACT FOR HOUSING ISSUES Note: when dialing from the U.S. -

Best Warrior 2020” Competition

Vol. 49, No. 3, March 2020 Serving the Greater Stuttgart Military Community www.stuttgartcitizen.com Thirteen top Soldiers from across Europe converged at U.S. Army Garrison Stuttgart from March 1-4 to compete in Installation Management Command — Europe’s “Best Warrior 2020” competition. The event began with a ruck march. To see more images from the competition, turn to page 5. The full story can be found on StuttgartCitizen.com. Photo by Jason Johnston, TSC Stuttgart Best Warrior 2020 US military chefs take silver at culinary olympics By Sgt. Alexis Gonzalez American Forces Network, Stuttgart U.S. military chefs showed their love of cooking over Valentine’s Day weekend during the 2020 Internationale Kochkunst Ausstellung culinary olympics. Nearly 1,800 top chefs from around the globe took part in the event, held Feb. 14-19 at the Stuttgart Messe in Leinfelden-Echterdingen. The U.S. Army Culinary Arts Team competed on Sunday, Feb. 16. Among military teams, the U.S. team ranked second overall, earning the silver medal. The Swiss Armed Forces Culinary Team took gold. The teams from Germany, Britain, and Hungary fi nished third, fourth, and fi fth, respectively. The competition was fi erce. Military chefs bent over shining white plates teeming with roasted meats, vegetables and decadent sweets in their assigned kitchen. Behind the scenes, the U.S. military team effort was what truly made them champions. Arriving at 5:30 a.m. on the morning of their test, they set up their Staff Sgt. Marc Susa USACAT team leader puts the fi nal touches on the starter at the 2020 IKA Culinary Olympics, Feb. -

A Return to the Town Square

2017 INTERNATIONAL MAKING CITIES LIVABLE CONFERENCE A Return to the Town Square Stephanie Rouse June 6, 2017 The town square was an integral city function for centuries throughout the world. It was the central hub of activity, a place for gathering to celebrate, receive information, conduct business, and to simply sit. They have changed over time, losing prominence in recent decades with attitudes changing about society and how we interact. Before technology took off and created an environment that allowed for information at your fingertips, individuals gathered in town squares to share information, discuss politics, and transact business. It has since become a barrier to genuine interaction. Most engagement today is done through social media, email, and video chats. While these forms of communication can be useful when working in a global economy, we cannot forget the value derived from speaking in person. The classic town square can be reimagined to function as it used to, to bring people together to interact face to face and create an educated and active society. We can use the town square as an inviting place that allows people to gather to celebrate, conduct business, and engage in discussion. We may not need the town square to disseminate information, but it can still give us the environment to interact face to face again. There is a way to bring back the historic town square to build on the original values in the new era of design and information. 2 | Page A Return to the Town Square by Stephanie Rouse Most town squares in the United States are a piece of art, rather than a fully functioning space. -

Fully Escorted Tours of Italy

LOW SEASON ENGLISH 2020 / 2021 FULLY ESCORTED TOURS OF ITALY Our tours are guaranteed in English Regular guaranteed departures to discover Italy at its best! Several travelling options from 3 nights to 11 nights Iconic cities like Rome, Florence and Venice; the Tuscany Wine Region; the wonderful South with Sorrentine Coast and Sicily Selected Hotels & typical Italian meals We work only with the best licensed Guides: quality assured! EN_FANTASIA LS20_21 LOW SEASON 2020-21 ENGLISH Fully Escorted Tours of Italy • Our tours are guaranteed in English • Regular guaranteed departures to discover Italy at its best! • Several travelling options from 3 nights to 11 nights • Iconic cities like Rome, Florence and Venice; the Tuscany Wine Region; the wonderful South with Sorrentine Coast and Sicily • Selected Hotels & typical Italian meals • We work only with the best licensed Guides: quality assured! 1 Useful information before booking our Fantasia tours Meeting Point and Time: Fantasia departs from the Hotel Massimo D’Azeglio in Rome at 7:15 am The Tour includes: • Transportation by deluxe motorcoach • Monolingual Tour-escort in English • Accommodation in 4 stars or 3 stars hotels • Meals as per itinerary (please inform us at the moment of the booking, in case of any food allergy or alimentary restriction) • Entrance tickets to the archaeological site in Pompeii with “Skip the Line” (when included in the itinerary) • Entrance tickets to Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel and St. Peter’s Basilica with “Skip the Line” (when included in the itinerary) -

With Project for Public Spaces Imagine a Town Square

Placemaking with Project for Public Spaces Imagine a town square... Since 1975, we have worked in more than 2,000 communities in 26 countries around the world, helping people turn their public spaces into vital community places, with programs, uses, and people-friendly settings that build local value and serve community needs. Project for Public Spaces Project for Public Spaces is a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping people create and sustain public spaces that build stronger communities. Founded in 1975, PPS embraces the insights of William (Holly) Whyte, a pioneer in understanding the way people use public spaces. Today, PPS has become an internationally recognized center for best-practices, information, and resources about Placemaking. We provide: l Place-based Planning and Design; l PlacemakingTraining and Education; l Public Space Advocacy. What does PPS bring? l Our deep understanding of how successful places work, based on more than 30 years of experience and research. l Our belief that the community is the expert. l Our ability to translate community visions into actions in a range of diverse settings and contexts around the world. l Our commitment to always determine a program of uses before developing a formal design. ...bustling with people who are greeting each other, l Our support for people who care about sustainable buying, selling, and exchanging ideas. For everyone striving to make public development of communities by providing them with the resources, skills, networks, and knowledge to become spaces better, PPS is that town square. Our vision is to act as the central hub successful Placemakers. of the global Placemaking movement, connecting people to ideas, expertise, l Our worldwide experience with a variety of countries, and partners who share a passion for creating vital places. -

T O W N O F E M M I T S B U R G T O W N S Q U a R E R E V I T a L I Z a T I O N S

Town of Emmitsburg Town Square Revitalization S t r a t e g y From Emmitsburg Area Historical Society - Motorcycle Club in front of the post office 1920s J u n e 2 0 1 3 Seth Harry & Associates, Inc. in collaboration with Townscape Design and CMS Associates Seth Harry & Associates, Inc. Town of Emmitsburg in collaboration with Townscape Design and CMS Associates Town Square Revitalization ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS TOWN OF EMMITSBURG CONSULTING TEAM Donald Briggs, MAI, LEED AP+, Mayor Seth Harry & Associates, Inc. Dave Haller, Town Manager Seth Harry, AIA, NCARB Susan Cipperly, AICP, Town Planner Ruth Landsman, RA, NCARB, LEED AP Patrick Zimmerman STATE HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION, DISTRICT 7 Dave Coyne, District Engineer Townscape Design, LLC Mark Crampton David Ager, AICP, ASLA, LEED AP ND Samuel Delaurence John Concannon CMS Associates Geoffrey Cinerio, PE FREDERICK COUNTY Denis Superczynski, Senior Planner Also, the Consultant Team would like to express its appreciation to the residents, Funding for the design of the revitalization for the Square is businesses, and property owners in the provided through a grant from the Maryland Heritage Areas town of Emmitsburg, for their input and Authority (MHAA). MHAA provides matching grants to participation in this project. governments for historical and cultural sites in a Maryland Certified Heritage Area (CHA). It is the hope that through this grant the town of Emmitsburg can design a Square that pays tribute to the historic location within the CHA and promotes heritage tourism. Acknowledgements Town of Emmitsburg Seth Harry & Associates, Inc. Town Square Revitalization in collaboration with Townscape Design and CMS Associates Seth Harry & Associates, Inc. -

Hexagonal Planning in Theory and Practice

Journal ofUrban Design,Vol. 5, No. 3, 237± 265, 2000 Hexagonal Planningin Theoryand Practice ERANBEN-JOSEPH & DAVIDGORDON ABSTRACT Residentialneighbourhood designs with street patterns basedupon hexagonal blockswere proposedby several planners in theearly 20th century. Urban designerssuch asCharles Lamb, NoulanCauchon and Barry Parker demonstrated the economic advan- tagesand ef® cient landuse generatedby hexagonal plans. By 1930, hexagonal planning was aleadingtheoretical alternative to therectangular gridfor residential subdivisions, but itwas displacedby the loop and cul-de-sac modeldeveloped in Radburn, New Jersey, byClarence Stein andHenry Wright.The paper chronologically reviews the various hexagonalplanning schemes andtheir designers. It considersthe advantages and disad- vantagesof hexagons, using their designers’ own wordsand drawings. Introduction In the realmof urban design, hexagonalplanning istoday virtually an unknown phenomenon, amere oddityamong a vastarray of ideologies, theories and methods.It regularly goesunnoticed by studentsof city planning andurban history.Yet, for a period of almost30 years, between 1904and 1934, it caught the attentionof variousplanners, engineers andarchitects who saw in ita promisingpanacea for the city’splanning illsand a replacement forthe uniform rectangularstreet grid. Striving toestablish visionary and idealistic schemes for aperfect physicalenvironment that would also improve social conditions, these individualsadvocated their ideasin papers andprofessional presentations for overa quarterof -

Facebook: the New Town Square

[MACRO] PUETZ_FINAL_4.11.2015 (DO NOT DELETE) 4/11/2015 9:24 PM FACEBOOK: THE NEW TOWN SQUARE I. INTRODUCTION Once only a part of science fiction and the imagination, the idea of a virtual community is now a reality.1 The question, however, is how the First Amendment applies to this new reality.2 Centered on self-expression and the sharing of content,3 social networking sites (SNS) are now one of the strongest avenues for self-expression and are dependent upon freedom of speech.4 Since SNS exploded onto the technology scene in the late 1990s, people have flocked to them, and they have become increasingly prevalent.5 Of the SNS available, Facebook has become far and away the most popular.6 In fact, Facebook has become so well-liked and so important in 1. Peter Sinclair, Freedom of Speech in the Virtual World, 19 ALB. L.J. SCI. & TECH. 232 (2009). 2. U.S. CONST. amend. I (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”). 3. Social Networking, Investopedia, http://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/social- networking.asp (last visited Oct. 12, 2014). 4. Pialamode314, Web Event 1: Self-Expression and Gender Identity on Facebook, SERENDIP STUDIO (Oct. 05, 2013, 1:07 PM), http://serendip.brynmawr.edu/exchange/critical- feminist-studies-2013/pialamode314/web-event-1-self-expression-and-gender-identity-facebook (noting that people use Facebook to express themselves, and have “freedom to customize their Facebook profiles to portray the person they believe themselves to be, or aspire to be .