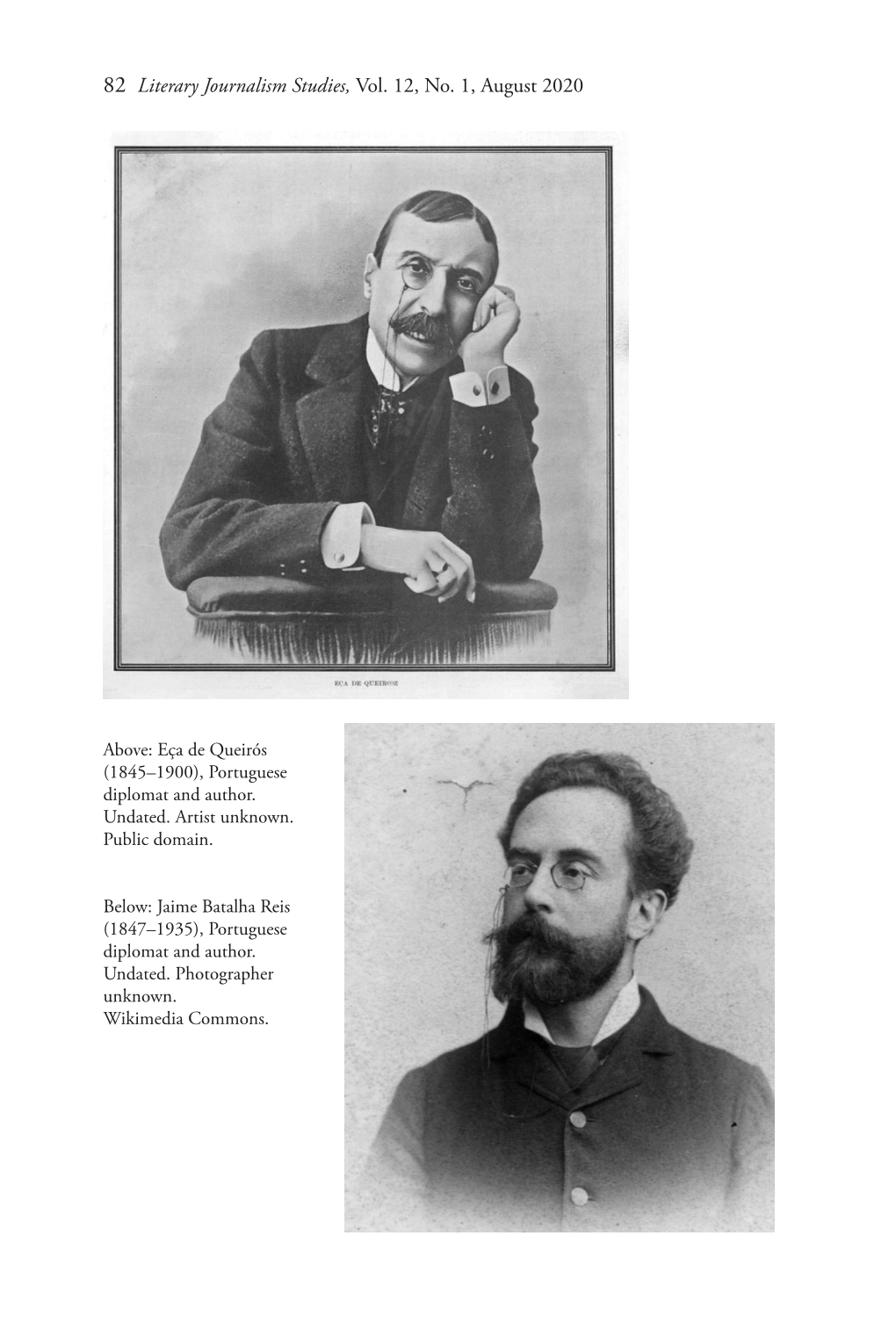

82 Literary Journalism Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1, August 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civilizing Africa” in Portuguese Narratives of the 1870’S and 1880’S Luísa Leal De Faria

Empire Building and Modernity Organização Adelaide Meira Serras Lisboa 2011 EMPIRE BUILDING AND MODERNITY ORGANIZAÇÃO Adelaide Meira Serras CAPA, PAGINAÇÃO E ARTE FINAL Inês Mateus Imagem na capa The British Empire, 1886, M. P. Formerly EDIÇÃO Centro de Estudos Anglísticos da Universidade de Lisboa IMPRESSÃO E ACABAMENTO TEXTYPE TIRAGEM 200 exemplares ISBN 978-972-8886-17-2 DEPÓSITO LEGAL 335129/11 PUBLICAÇÃO APOIADA PELA FUNDAÇÃO PARA A CIÊNCIA E A TECNOLOGIA ÍNDICE Foreword Luísa Leal de Faria . 7 Empire and cultural appropriation. African artifacts and the birth of museums Cristina Baptista . 9 Here nor there: writing outside the mother tongue Elleke Boehmer . 21 In Black and White. “Civilizing Africa” in Portuguese narratives of the 1870’s and 1880’s Luísa Leal de Faria . 31 Inverted Priorities: L. T. Hobhouse’s Critical Voice in the Context of Imperial Expansion Carla Larouco Gomes . 45 Ways of Reading Victoria’s Empire Teresa de Ataíde Malafaia . 57 “Buy the World a Coke:” Rang de Basanti and Coca-colonisation Ana Cristina Mendes . 67 New Imperialism, Colonial Masculinity and the Science of Race Iolanda Ramos . 77 Challenges and Deadlocks in the Making of the Third Portuguese Empire (1875-1930) José Miguel Sardica . 105 The History of the Sevarambians: The Colonial Utopian Novel, a Challenge to the 18th Century English Culture Adelaide Meira Serras . 129 Isaiah Berlin and the Anglo-American Predicament Elisabete Mendes Silva . 143 Nabobs and the Foundation of the British Empire in India Isabel Simões-Ferreira . 155 Foreword ollowing the organization, in 2009, of the first conference on The British Empire: Ideology, Perspectives, Perception, the Research Group dedicated Fto Culture Studies at the University of the Lisbon Centre for English Studies organized, in 2010, a second conference under the general title Empire Building and Modernity. -

Expert at a Distance

EXPERT AT A DISTANCE BARBOSA DU BOCAGE AND THE PRODUCTION OF SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE ON AFRICA Catarina Madruga CIUHCT ‒ Centro Interuniversitário de História das Ciências e da Tecnologia Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal [email protected] ABSTRACT: The career of José Vicente Barbosa du Bocage (1823‒1907) as director of the Zoological Section of the Museu Nacional de Lisboa (National Museum of Lisbon) followed by the presidency of the Society of Geography of Lisbon is presented in this paper as an example of transfer of expertise between scientific fields, specifically from zoology to geography. Additionally, it explores the connection between scientific credit and political recognition, in the sense of the conflation of Bocage’s taxonomical and zoogeographical work with the colonial agenda of his time. Although Bocage himself never visited Africa, he was part of a generation of Africanists who were members of the Portuguese elite dedicated to African matters and considered exemplary custodians of the political and diplomatic Portuguese international position regarding its African territories. Keywords: Expertise, zoogeography, science and empire, Africa, nineteenth century INTRODUCTION: BARBOSA DU BOCAGE, A NATURALIST QUA GEOGRAPHER In February 1883, the cover of the Diario Illustrado, a Lisbon daily newspaper, featured an article dedicated to José Vicente Barbosa du Bocage (1823‒1907) a member of the Portuguese scientific and political elite, and a well-known zoologist.1 The illustrated text is 1 Alberto Rocha, “Dr. Bocage,” Diario Illustrado, (February 12) 1883, 3508: 1‒2. For a periodisation and analysis of the biographical notes dedicated to Bocage see: Catarina Madruga, José Vicente Barbosa du Bocage (1823-1907). -

History, Cartography and Science: the Present Day Importance of the Mapping of Mozambique in the 19Th Century

History, Cartography and Science: The Present Day Importance of the Mapping of Mozambique in the 19th Century Ana Cristina ROQUE and Paula SANTOS, Portugal Key words: Cartography, History, Mozambique SUMMARY In the late 19th century Mozambique territory was subjected to deep systematic surveys in order to map both the coastal situation and all the territory proclaimed under Portuguese sovereignty. Although trying to respond efficiently to the Berlin Conference decisions of 1885, Portuguese were committed, since 1883, in the making of an Atlas of the overseas territories claimed to be under Portuguese control since the 16th century. This claim was particularly relevant for the East African Coast where those territories were in the mid 19th century disputed by the British and the Germans. Within this scenario and to sustain the Portuguese pretensions, the Portuguese government created in 1883 the Portuguese Commission of Cartography (PCC), an operative institution that should bring together the mapping of the colonial overseas territories and the necessary studies to support it. The first missions were carried out in Mozambique, as early as 1884, and they marked the beginning of a series of survey and scientific missions. The result was the entire recognition of the coast and the production of the first hydrographic maps on this specific area. As the PPC ensured both the cartographic coverage of the coast and of the inland, the analysis and evaluation of its work must consider either the scientific methods and instruments used or the cooperation work with Navy, responsible for the permanent and update survey of the coast, and with he Army and the special Commissions for the Delimitations of the Frontiers of the different areas of Mozambique operating in the territory at the time. -

A Ideia De Império Na Propaganda Do Estado Novo Autor(Es): Garcia

A ideia de império na propaganda do Estado Novo Autor(es): Garcia, José Luís Lima Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/42061 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-8925_14_18 Accessed : 9-Oct-2021 20:10:23 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. impactum.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt Revista de Historia das Ideias JOSÉ LUÍS LIMA GARCIA Vol. 14 (1992) A IDEIA DE IMPÉRIO NA PROPAGANDA DO ESTADO NOVO 1. O Estatuto Jurídico do Império no Estado Novo Quando inserimos esta problemática, no cerne da investigação que presentemente realizamos, fazemo-lo corn a expectativa e a dúvida cartesianas que sempre deverão presidir como hipóteses de trabalho, a uma qualquer investigação. -

Scanned by Scan2net

ÜaHiiliiiallyäÜililäliMyi N^nMIUìf ^ Ì cIkk IKHi IHfl Hit jjj frli îffif iiìil&r âïî -if ;:jj European University Institute Firenze Department of History and Civilization HUBERT ZIMMERMANN DOLLARS, POUNDS, AND TRANSATLANTIC SECURITY ?img ïr.ïit:!:*S CONVENTIONAL TROOPS AND MONETARY POLICY IN GERMANY'S RELATIONS TO THE UNITED STATES AND THE UNITED KINGDOM 1955-1967 ♦' Ti; Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of doctor of the European University Institute Florence, January 1997 Examining Jury: Prof. Richard T. Griffiths (Supervisor}, EUI Prof. Werner Abelshauser, Universität Bielefeld I Prof. Wolfgang Eriecer, Universität Marburg .Prof. Alan S. Milward, EUI ;7--f : J - r > Prof. Gustav Schmidt, Universität Bochum i X t i : H iaSSSi EUROPEAN UWVERSITY INSTITUTE IIMlII.IIIilllMiM 111. U1 1 I .1 LI. 3 0001 0025 6848 5 i 3*3. o m F ■312. 2 i F B3B09 European University Institute Firenze Department of History and Civilization HUBERT ZIMMERMANN DOLLARS, POUNDS, AND TRANSATLANTIC SECURITY: CONVENTIONAL TROOPS AND MONETARY POLICY IN GERMANY' S RELATIONS TO THE UNITED STATES AND THE UNITED KINGDOM 1955-1967 Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of doctor of the European University Institute LIB 9 4 3 . 0 8 7 5 -F ZIM Florence, January 1997. Examining Jury Prof. Richard T. Griffiths (Supervisor), EUI Prof. Werner Abelshauser, Universität Bielefeld Prof. Wolfgang Krieger, Universität Marburg Prof. Alan S. Milward, EUI Prof. Gustav Schmidt, Universität Bochum LIST OF CONTENTS Key to abbreviations -

Biografia De João Carlos De Brito Capelo

André Pires Fernandes Biografia de João Carlos de Brito Capelo Dissertação para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Ciências Militares Navais, na especialidade de Marinha Alfeite 2017 André Pires Fernandes Biografia de João Carlos de Brito Capelo Dissertação para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Ciências Militares Navais, na especialidade de Marinha Orientação de: O Aluno Mestrando O Orientador ___________________ ___________________ ASPOF M Pires Fernandes CMG M Costa Canas Alfeite 2017 Epígrafe “If it’s a good idea, go ahead and do it. It’s much easier to apologize than it is to get permission.” Grace Hopper, United States Navy Rear Admiral III IV Dedicatória Aos autores da minha presença neste mundo, por terem sido os promotores incansáveis das minhas melhores realizações e os meus apoiantes infatigáveis da progressão dos meus estudos. Por fim, surge-me a necessidade de exprimir o meu extremo carinho e amor, por ti, amor da minha vida. Obrigada por estares sempre a meu lado. V VI Agradecimentos A exposição que a seguir se segue, não fará, possivelmente, justiça a todos aqueles que direta ou indiretamente prestaram tributo para a conquista do projeto implícito ao seguinte trabalho. Apesar desta referência, estou certo, que farei, seguramente, a inclusão de todos aqueles, cuja omissão seria um erro execrável. Começo então por fazer menção com o maior reconhecimento, ao Capitão de Mar e Guerra Costa Canas, por me ter sugerido o desenvolvimento desta temática, à qual inicialmente me demonstrei relutante, contundo, apenas as palavras sábias deste grande Senhor me demoveram e me fizeram seguir esta via. Mas não só por isto lhe posso estar agradecido, também lhe tenho de tirar o chapéu por me ter assegurado que esta caminhada não seria um percurso em escuro, porque honestamente sem o seu conhecimento e disponibilidade, o caminho teria sido mais íngreme. -

The Case of Napoleon Bonaparte Reflections on the Bicentenary of His Death

Working Paper 2021/18/TOM History Lessons: The Case of Napoleon Bonaparte Reflections on the Bicentenary of his Death Ludo Van der Heyden INSEAD, [email protected] April 26, 2021 In this article we reassess the myth of Napoleon Bonaparte, not so much from the standpoint of battles and conquests, but more from the point of view of justice, particularly procedural justice. This approach allows us to define the righteous leader as one who applies procedural justice. Using this concept, we aim to demonstrate that General Bonaparte could be considered as a just leader, although, in the guise of Emperor, he will be qualified here as the antithesis of that. The inevitable conclusion is that the Empire came to an end as a predictable consequence of Emperor Napoleon's unjust leadership. We recognize that the revolutionary aspirations of Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité were in themselves noble, but that they required for their implementation a system of procedural justice central to the resolution of the inevitable tensions and contradictions that these precepts would generate. We conclude by highlighting and examining how the notion of procedural justice is vital to the proper functioning of the modern European Union. In contrast, the difficulties presented by Brexit, or the Trump presidency, can be seen as the tragic, but also predictable consequences of an unjust leadership. We revisit the urgent need for fair management and debate; debate that can only take place when guided by righteous leaders. The imperial failure was a consequence of the drift towards injustice in the management of Empire. -

Timeline / 1810 to 1900 / PORTUGAL / TRAVELLING

Timeline / 1810 to 1900 / PORTUGAL / TRAVELLING Date Country Theme 1838 Portugal Travelling Building of Pena Palace in Sintra, close to Lisbon, begins. This eclectic summer residence, commissioned by King Fernando II, combines Neo-Manueline, Neo- Islamic and Neo-Renaissance styles. The use of the Islamic decorative influences in a royal palace contributes to the Portuguese society’s acknowledgement of its Islamic past. 1839 Portugal Travelling Silva Porto, born in poverty in Portugal, trader, farmer and explorer, settles in Bié, Angola, from where he, with his pombeiros (long-distance trade agents), tours Central Africa between 1839 and 1890. The descriptions of his travels that he sent to Lisbon became legendary and a precious source of data. 1860 Portugal Travelling Travelling became a great cultural and social phenomenon with Romanticism. The “Grand Tour” through the countries of the known world, namely around the Mediterranean, became a means of developing cultural and social skills. Travel became refined and even a simple journey to the countryside required such accessories as this travel case for meals. 1875 Portugal Travelling Aware that Portuguese empirical knowledge of Central Africa was being overtaken by other countries, the “Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa” is founded to "promote and assist the study and progress of geography and related sciences in Portugal". To raise awareness of the colonial Portuguese possessions in Africa and Asia was also a goal. 1877 Portugal Travelling Hermenegildo Capelo, Roberto Ivens and Serpa Pinto appointed to organise an expedition to southern Africa. After a briefing by Silva Porto in Bié, they chose separate itineraries. Capelo and Ivens focus on the Kwanza and Kuangu rivers and on the Yaka people. -

The Nation, the State, and the First Industrial Revolution

The Nation, the State, and the First Industrial Revolution Julian Hoppit he nation-state has long offered a powerful framework within which T to understand modern economic growth. To some it provides “a natural unit in the study of economic growth,” especially when measuring such growth; to many others states have often significantly influenced the performance of their economies.1 On this second point Barry Supple observed that “frontiers are more than lines on a map: they frequently define quite distinctive systems of thought and action. The state is, of course, pre-eminently such a system.”2 In the British case, however, national frontiers have long been highly distinctive, as has recently been made plain by the “new British history” and work by political sci- entists on devolution since 1997.3 By exploring patterns of the use of legislation for economic ends, this article considers the implications of such distinctiveness for the relationship between the nation-state and Britain’s precocious economy between 1660 and 1800. The focus is mainly upon legislation at Westminster, but comparisons are also made with enactments at Edinburgh and Dublin to enrich the account. It is argued that if Julian Hoppit is Astor Professor of British History at University College London. 1 Simon Kuznets, “The State as a Unit of Economic Growth,” Journal of Economic History 11, no. 1 (Winter 1951): 25–41. Work within the regional and global frameworks in recent decades has pointed up the limitations of an exclusive use of the nation as the unit of assessment and analysis. A very useful summary of the regional approach is provided in Pat Hudson, ed., Regions and Industries: A Perspective on the Industrial Revolution in Britain (Cambridge, 1989). -

Timeline / 1870 to After 1930 / PORTUGAL / ALL THEMES

Timeline / 1870 to After 1930 / PORTUGAL / ALL THEMES Date Country Theme 1870 Portugal Reforms And Social Changes Publication of Joao de Deus’s Cartilha Maternal, a beginner’s reading book that was to be in use for a long time. João de Deus was a follower of Maria Montessori’s pedagogical theories and founded in Portugal the “Escola Nova” movement. 1872 - 1874 Portugal Fine And Applied Arts O Desterrado (The Outcast), a sculpture by António Soares dos Reis (1847–89) is an idealised self-portrait. It conveys the collective feelings of his contemporary intellectuals and the feelings of loneliness and longing common to those who had left their homeland. The sculptor’s romantic sensibility enabled him to shape feelings and psychological tensions in the marble. 1873 Portugal Reforms And Social Changes A primary school building to be built in wood attracts the attention of visitors to the Portuguese stand at the “Weltausstellung” (world exposition) in Vienna. 1875 - 1876 Portugal Economy And Trade In 1875 the French government convenes the Diplomatic Conference of the Metre that proclaims the Metre Convention. Portugal receives the tenth copies of the metric and kilogram standards. 1875 Portugal Travelling Aware that Portuguese empirical knowledge of Central Africa was being overtaken by other countries, the “Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa” is founded to "promote and assist the study and progress of geography and related sciences in Portugal". To raise awareness of the colonial Portuguese possessions in Africa and Asia was also a goal. 1876 - 1881 Portugal Cities And Urban Spaces The "Urban General Improvements Plan for Lisbon" (Commission of 1876–81) designs wide, straight roads – modern boulevards – to define orthogonal blocks for buildings, with roundabouts, pavements, vegetation and street furniture namely at Avenida 24 de Julho, Avenida da Liberdade and covering the area from Picoas to Campo Grande. -

Timeline / 1830 to 1920 / PORTUGAL / TRAVELLING

Timeline / 1830 to 1920 / PORTUGAL / TRAVELLING Date Country Theme 1838 Portugal Travelling Building of Pena Palace in Sintra, close to Lisbon, begins. This eclectic summer residence, commissioned by King Fernando II, combines Neo-Manueline, Neo- Islamic and Neo-Renaissance styles. The use of the Islamic decorative influences in a royal palace contributes to the Portuguese society’s acknowledgement of its Islamic past. 1839 Portugal Travelling Silva Porto, born in poverty in Portugal, trader, farmer and explorer, settles in Bié, Angola, from where he, with his pombeiros (long-distance trade agents), tours Central Africa between 1839 and 1890. The descriptions of his travels that he sent to Lisbon became legendary and a precious source of data. 1860 Portugal Travelling Travelling became a great cultural and social phenomenon with Romanticism. The “Grand Tour” through the countries of the known world, namely around the Mediterranean, became a means of developing cultural and social skills. Travel became refined and even a simple journey to the countryside required such accessories as this travel case for meals. 1875 Portugal Travelling Aware that Portuguese empirical knowledge of Central Africa was being overtaken by other countries, the “Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa” is founded to "promote and assist the study and progress of geography and related sciences in Portugal". To raise awareness of the colonial Portuguese possessions in Africa and Asia was also a goal. 1877 Portugal Travelling Hermenegildo Capelo, Roberto Ivens and Serpa Pinto appointed to organise an expedition to southern Africa. After a briefing by Silva Porto in Bié, they chose separate itineraries. Capelo and Ivens focus on the Kwanza and Kuangu rivers and on the Yaka people. -

Hg-15911-V 0000 1-352 T24-C-R0150.Pdf

EXPOSIÇÃO HISTÓRICA DA OCUPACÃO / II VOLUME agência geral das colónias 19 3 7 da EXPOSIÇÃO HISTÓRICA DA OCUPAÇÃO DEP. LEG. ' ;ír 0 \\ km s REPÚBLICA PORTUGUESA MINISTÉRIO DAS COLÓNIAS /V r,,i t EXPOSIÇÃO HISTÓRICA DA OC UPAÇAO II VOLUME AGÊNCIA GERAL DAS COLÓNIAS 19 3 7 ? 6 IC O 1.A GALERIA PENETRAÇÃO E POVOAMENTO ENETRAÇÃO, povoamento... — mas é tôda a coloni- zação! Obra que não é de hoje, nem de um século, — mas que começa no próprio dia da invenção pelos portu- gueses do Mundo até at ignorado. Chegados os navegadores até às novas paragens povoa- das, logo a ânsia lusíada buscava inquietamente descobrir, depois das terras, as riquezas, as gentes e os costumes; e nunca houve curiosidade mais viva e audaz, nem sensações mais frescas e perturbantes que as dos soldados, dos missio- nários, dos aventureiros portugueses entranhados na rudeza da barbarie ou no mistério subtil de milenárias civilizações. Levados pelo espirito de aventura, pelo ardor evan- gélico ou pela cobiça do oiro, ei-los que navegam rios e esca- lam montes, que travam relações com indígenas, que se em- brenham em florestas inexploradas, que palmilham a Pérsia, a China e o Japão, vivendo incríveis lances e triunfando por admiráveis rasgos. 7 Assim correu a fase heróica da penetração, de carácter sobretudo individual: quantas vezes um só português não conquista, pela persuação e pelo prestígio pessoal, tribus e reinos para os vir depor aos pés do seu rei! É que no cora- ção de cada um dêsses arrojados exploradores iam, inteiras, as aspirações imperiais e os ideais da civilização da sua pátria! Mas a penetração não se féz só assim, caprichosamente, ao sabor da imaginação e da vontade de portugueses isolados: também revestiu outras vezes aspecto metódico, seguindo um plano, ora por meio de entendimentos diplomáticos com os soberanos locais, ora por lenta infiltração pacífica, ora sob a forma de expedições punitivas ou visando a mera afirmação de poderio.