Contested Pilgrimage: Shikoku Henro and Dark Tourism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geography & Climate

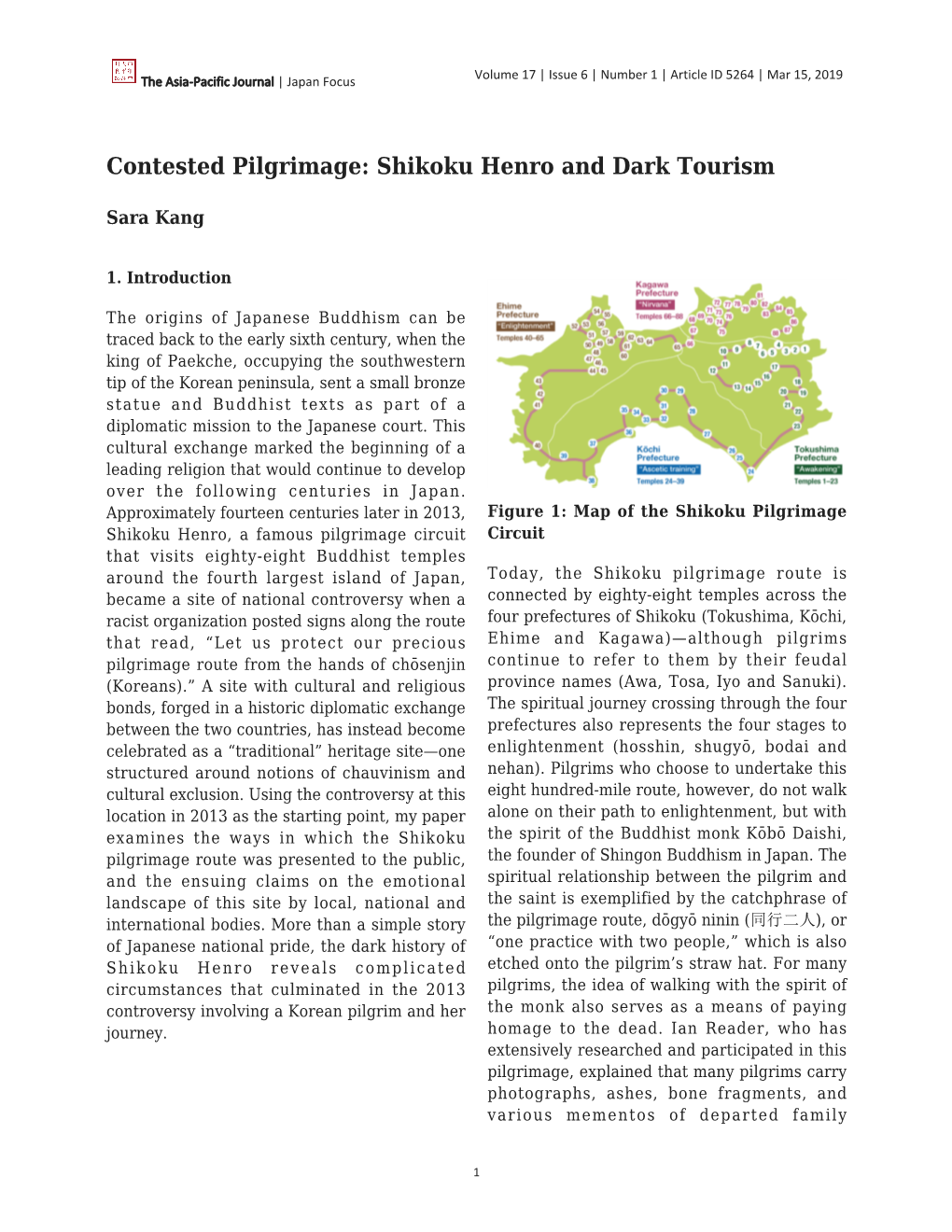

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE A country of diverse topography and climate characterized by peninsulas and inlets and Geography offshore islands (like the Goto archipelago and the islands of Tsushima and Iki, which are part of that prefecture). There are also A Pacific Island Country accidented areas of the coast with many Japan is an island country forming an arc in inlets and steep cliffs caused by the the Pacific Ocean to the east of the Asian submersion of part of the former coastline due continent. The land comprises four large to changes in the Earth’s crust. islands named (in decreasing order of size) A warm ocean current known as the Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku, Kuroshio (or Japan Current) flows together with many smaller islands. The northeastward along the southern part of the Pacific Ocean lies to the east while the Sea of Japanese archipelago, and a branch of it, Japan and the East China Sea separate known as the Tsushima Current, flows into Japan from the Asian continent. the Sea of Japan along the west side of the In terms of latitude, Japan coincides country. From the north, a cold current known approximately with the Mediterranean Sea as the Oyashio (or Chishima Current) flows and with the city of Los Angeles in North south along Japan’s east coast, and a branch America. Paris and London have latitudes of it, called the Liman Current, enters the Sea somewhat to the north of the northern tip of of Japan from the north. The mixing of these Hokkaido. -

Excerpts for Distribution

EXCERPTS FOR DISTRIBUTION Two Shores of Zen An American Monk’s Japan _____________________________ Jiryu Mark Rutschman-Byler Order the book at WWW.LULU.COM/SHORESOFZEN Join the conversation at WWW.SHORESOFZEN.COM NO ZEN IN THE WEST When a young American Buddhist monk can no longer bear the pop-psychology, sexual intrigue, and free-flowing peanut butter that he insists pollute his spiritual community, he sets out for Japan on an archetypal journey to find “True Zen,” a magical elixir to relieve all suffering. Arriving at an austere Japanese monastery and meeting a fierce old Zen Master, he feels confirmed in his suspicion that the Western Buddhist approach is a spineless imitation of authentic spiritual effort. However, over the course of a year and a half of bitter initiations, relentless meditation and labor, intense cold, brutal discipline, insanity, overwhelming lust, and false breakthroughs, he grows disenchanted with the Asian model as well. Finally completing the classic journey of the seeker who travels far to discover the home he has left, he returns to the U.S. with a more mature appreciation of Western Buddhism and a new confidence in his life as it is. Two Shores of Zen weaves together scenes from Japanese and American Zen to offer a timely, compelling contribution to the ongoing conversation about Western Buddhism’s stark departures from Asian traditions. How far has Western Buddhism come from its roots, or indeed how far has it fallen? JIRYU MARK RUTSCHMAN-BYLER is a Soto Zen priest in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. He has lived in Buddhist temples and monasteries in the U.S. -

Chugoku・Shikoku Japan

in CHUGOKU・SHIKOKU JAPAN A map introducing facilities related to food and agriculture in the Chugoku-Shikoku Tottori Shimane Eat Okayama Hiroshima Yamaguchi Stay Kagawa Tokushima Ehime Kochi Experience Rice cake making Sightseeing Rice -planting 疏水のある風景写真コンテスト2010 Soba making 入選作品 題名「春うらら」 第13回しまねの農村景観フォトコンテスト入賞作品 第19回しまねの農村景観フォトコンテスト入賞作品 Chugoku-shikoku Regional Agricultural Administration Office Oki 26 【Chugoku Region】 7 13 9 8 Tottori sand dunes 5 3 1 Bullet train 14 2 25 4 16 17 11 Tottori Railway 36 15 12 6 Izumo Taisha 41 Matsue Tottori Pref. Shrine 18 Kurayoshi Expressway 37 10 Shimane Pref. 47 24 45 27 31 22 42 43 35 19 55 28 Iwami Silver Mine 48 38 50 44 29 33 34 32 30 Okayama Pref. 39 23 20 54 53 46 40 49 57 Okayama 21 Okayama 52 51 Kurashiki Korakuen 59 Hiroshima Pref. 60 64 79 75 76 80 62 Hiroshima Fukuyama Hagi 61 58 67 56 Atom Bomb Dome Great Seto Bridge 74 Yamaguchi Pref.Yamaguchi Kagawa Pref. 77 63 Miyajima Kintaikyo 68 69 Bridge Tokushima Pref. Shimonoseki 66 65 72 73 Ehime Pref. 70 71 78 Tottori Prefecture No. Facility Item Operating hours Address Phone number・URL Supported (operation period) Access language Tourism farms 1206Yuyama,Fukube-cho,Tottori city Phone :0857-75-2175 Mikaen Pear picking No holiday during 1 English 味果園 (Aug.1- early Nov.) the period. 20 min by taxi from JR Tottori Station on the Sanin http://www.mikaen.jp/ main line 1074-1Hara,Yurihama Town,Tohaku-gun Phone :0858-34-2064 KOBAYASHI FARM Strawberry picking 8:00~ 2 English 小林農園 (early Mar.- late Jun.) Irregular holidays. -

Shikoku Access Map Matsuyama City & Tobe Town Area

Yoshikawa Interchange Hiroshima Airport Okayama Airport Okayama Kobe Suita Sanyo Expressway Kurashiki Junction Interchange Miki Junction Junction Junction Shikoku Himeji Tarumi Junction Itami Airport Hiroshima Nishiseto-Onomichi Sanyo Shinkansen Okayama Hinase Port Shin-Kobe Shin- Okayama Interchange Himeji Port Osaka Hiroshima Port Kure Port Port Obe Kobe Shinko Pier Uno Port Shodoshima Kaido Shimanami Port Tonosho Rural Experience Content Access Let's go Seto Ohashi Fukuda Port all the way for Port an exclusive (the Great Seto Bridge) Kusakabe Port Akashi Taka Ikeda Port experience! matsu Ohashi Shikoku, the journey with in. Port Sakate Port Matsubara Takamatsu Map Tadotsu Junction Imabari Kagawa Sakaide Takamatsu Prefecture Kansai International Imabari Junction Chuo Airport Matsuyama Sightseeing Port Iyosaijyo Interchange Interchange Niihama Awajishima Beppu Beppu Port Matsuyama Takamatsu Airport 11 11 Matsuyama Kawanoe Junction Saganoseki Port Tokushima Wakayama Oita Airport Matsuyama Iyo Komatsu Kawanoe Higashi Prefecture Naruto Interchange Misaki Interchange Junction Ikawa Ikeda Interchange Usuki Yawata Junction Wakimachi Wakayama Usuki Port Interchange hama Interchange Naruto Port Port Ozu Interchange Ehime Tokushima Prefecture Awa-Ikeda Tokushima Airport Saiki Yawatahama Port 33 32 Tokushima Port Saiki Port Uwajima Kochi 195 Interchange Hiwasa What Fun! Tsushima Iwamatsu Kubokawa Kochi Gomen Interchange Kochi Prefecture 56 Wakai Kanoura ■Legend Kochi Ryoma Shimantocho-Chuo 55 Airport Sukumo Interchange JR lines Sukumo Port Nakamura -

The Shikoku Pilgrimage – Visiting the Ancient Sites of Ko¯ Bo¯ Daishi

17 Chapter 16 HJB:Master Testpages HJB 10/10/07 11:43 Page 239 CHAPTER 16 THE SHIKOKU PILGRIMAGE – VISITING THE ANCIENT SITES OF KO¯ BO¯ DAISHI The shikoku pilgrimage is unlike the saikoku pilgrimage, where one visits the thirty-three sites of kannon, but rather it is a journey that consists of eighty-eight sites in shikoku, which are said to be the ancient sites of ko#bo# Daishi ku#kai. at each site, people pay homage at the Daishi hall. Both pilgrimages are similar in that one goes to sacred sites; however, the pilgrimage of shikoku has come to be traditionally called ‘shikoku henro’. The shikoku pilgrimage is said to be 1,400 kilometres long and takes fifty to sixty days for someone to walk the entire route. ryo#zenji, situated in Tokushima prefecture, has been designated as temple number one and o>kuboji, of kagawa prefecture, has been designated as temple number eighty-eight. actually, the ideal route is to begin at ryo#zenji in awa (Tokushima prefec- ture), then on to Tosa (ko#chi prefecture), then iyo (ehime prefecture), then sanuki (kagawa prefecture), arriving finally at Ōkuboji. Doing the pilgrimage in numerical order is called jun- uchi, while doing it all in reverse order, in other words, beginning at o>kuboji, is called gyaku-uchi. Origin of the number eighty-eight it is not at all clear what the significance of the number eighty- eight is, but there are various theories which offer possible explanations. For example, the character for ‘kome’, or rice, can be divided into three parts which read: eight, ten, eight or eighty- -

Pilgrimage to the 88 Temples of Shikoku Island: a Bibliography of Resources in English

Pilgrimage to the 88 Temples of Shikoku Island: A Bibliography of Resources in English Naomi Zimmer LIS 705, Fall 2005 The most widely known work in English about the Shikoku pilgrimage is undoubtedly Oliver Statler’s 1983 book Japanese Pilgrimage , which combines a personal account of Statler’s pilgrimage in Shikoku with substantial background and cultural information on the topic. The University of Hawaii’s Hamilton Library Japan Collection houses Statler’s personal papers in the Oliver Statler Collection , which includes several boxes of material related to the Shikoku pilgrimage. The Oliver Statler Collection is an unparalleled and one of a kind source of information in English on the Shikoku pilgrimage. The contents range from Statler’s detailed notes on each of the 88 temples to the original manuscript of Japanese Pilgrimage . Also included in the collection are several hand-written translations of previous works on the pilgrimage that were originally published in Japanese or languages other than English. The Oliver Statler Collection may be the only existing English translations of many of these works, as they were never published in English. The Collection also contains several photo albums documenting Statler’s pilgrimages on Shikoku taken between 1968 and 1979. A Pilgrimage to the 88 Temples in Shikoku Island (1973) is likely the earliest example of an English-language monograph on the specific topic of the Shikoku pilgrimage. This book, written by the Japanese author Mayumi Banzai, focuses on the legendary priest Kobo Daishi (774-835 A.D.) and the details of his association with the Shikoku pilgrimage. The books A Henro Pilgrimage Guide to the Eighty-eight Temples on Shikoku, Japan (Taisen Miyata), Echoes of Incense: a Pilgrimage in Japan (Don Weiss), The Traveler's Guide to Japanese Pilgrimages (Ed Readicker-Henderson), and Tales of a Summer Henro (Craig McLachlan) are all more recent personal accounts offering a less scholarly and more practical “guidebook” look at the pilgrimage. -

The Grass Flute Zen Master: Sodo Yokoyama

THE GRASS FLUTE ZEN MASTER ALSO BY ARTHUR BRAVERMAN Translations: Mud and Water: A Collection of Talks by Zen Master Bassui Warrior of Zen: The Diamond-hard Wisdom of Suzuki Shosan A Quiet Room: The Poetry of Zen Master Jakushitsu Non Fiction: Living and Dying in Zazen Fiction: Dharma Brothers: Kodo and Tokujo Bronx Park: A Pelham Parkway Tale Opposite: Yokoyama playing the grass flute at Kaikoen Park Copyright © 2017 by Arthur Braverman All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. Cover and Interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61902-892-0 COUNTERPOINT 2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318 Berkeley, CA 94710 www.counterpointpress.com Printed in the United States of America Distributed by Publishers Group West 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Ari, Oliver and Sanae: The next generation Contents 1. In Search of a Japanese Maharshi 2. Noodles and Memories of a Leaf-Blowing Monk 3. Sitting with Joko by the Bamboo Grove 4. The Magic Box with the Sound of the Universe 5. Fragrant Mist Travels a Thousand Leagues 6. A Pheasant Teaches Sodo-san about Zazen 7. Always a Little Out of Tune 8. Sodo-san, the Twentieth-Century Ryokan 9. Sodo-san’s Temple Under the Sky 10. Zazen Is Safe. This Life Is Easy. -

Medieval Japan

Medieval Japan Kingaku Temple in Kyoto, Japan A..D..300 A..D.7.700 1100 1500 c. A.D. 300 A.D.646 1192 c. 1300s Yayoi people Taika reforms Rule by Noh plays organize strengthen shoguns first into clans emperor’s powers begins performed Chapter Overview Visit ca.hss.glencoe.com for a preview of Chapter 5. Early Japan Physical geography plays a role in how civilizations develop. Japan’s islands and mountains have shaped its history. The Japanese developed their own unique culture but looked to China as a model. Shoguns and Samurai Conflict often brings about great change. Japan’s emperors lost power to military leaders. Warrior families and their followers fought each other for control of Japan. Life in Medieval Japan Religion influences how civilization develops and culture spreads. The religions of Shinto and Buddhism shaped Japan’s culture. Farmers, artisans, and merchants brought wealth to Japan. View the Chapter 5 video in the Glencoe Video Program. Categorizing Information Make this foldable to help you organize information about the history and culture of medieval Japan. Step 1 Mark the midpoint of the Step 2 Turn the Reading and Writing side edge of a sheet of paper. paper and fold in Jap an As you read the chapter, each outside edge organize your notes to touch at the by writing the main midpoint. Label ideas with supporting as shown. details under the appropriate heading. Draw a mark at the midpoint Early Shoguns and Life in Japan Samurai Medieval Japan Step 3 Open and label your foldable as shown. -

Opening the Hand of Thought : Approach To

TRANSLATED BY SHOHAKl AND TOM WRIGHT ARKANA OPENING THE HAND OF THOUGHT Kosho Uchiyama Roshi was born in Tokyo in 1911. He received a master's degree in Western philosophy at Waseda University in 1937 and became a Zen priest three years later under Kodo Sawaki Roshi. Upon Sawaki Roshi's death in 1965, he assumed the abbotship of Antaiji, a temple and monastery then located near Kyoto. Uchiyama Roshi developed the practice at Anataiji, including monthly five-day sesshins, and often traveled throughout Japan, lec- turing and leading sesshins. He retired from Antaiji in 1975 and now lives with his wife at N6ke-in, a small temple outside Kyoto. He has written over twenty texts on Zen, including translations of Dogen Zenji into modern Japanese with commentaries, one of which is available in English (Refining Your Life, Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1983). Uchiyama Roshi is also well known in the world of origami, of which he is a master; he has published several books on origami. Shohaku Okumura was born in Osaka, Japan, in 1948. He studied Zen Buddhism at Komazawa University in Tokyo and was ordained as a priest by Uchiyama Roshi in 1970, practicing under him at An- taiji. From 1975 to 1982 he practiced at the Pioneer Valley Zendo in Massachusetts. After he returned to Japan, he began translating Dogen Zenji's and Uchiyama Roshi's writings into English with Tom Wright and other American practitioners. From 1984 to 1992 Rev. Okumura led practice at Shorinji, near Kyoto, as a teacher of the Kyoto Soto Zen Center, working mainly with Westerners. -

Mind Moon Circle the Journal of the Sydney Zen Centre Autumn 2010 $6.00

MIND MOON CIRCLE THE JOURNAL OF THE SYDNEY ZEN CENTRE AUTUMN 2010 $6.00 Contents Robert Aitken Roshi Dana: The Way to Begin Sally Hopkins Poems inspired by Dogen and Uchiyama Jo Lindelauf Star Jasmine & the Boundary Fence Lee Nutter Two poems Glenys Jackson Lotus flowers Gillian Coote An Iron Boat Floats on Water Allan Marett Pilgrimage in Shikoku: challenges and renunciations Sue Bidwell A Small Field Janet Selby The Practice of Dana and Clay Philip Long Giving the Self Carl Hooper From Disguised Nonsense to Patent Nonsense: Some remarks on Zen and Wittengenstein Han-shan The unfortunate human disorder Gillian Coote, Sally Hopkins Editors Cover photo, from Fifty Views of Japan, l905, Frank Lloyd Wright __________________________________________________________________________ Allan Marett, editor of the Winter Issue writes, ‘Accounts of Buddhism in India are full of magical and mysterious happenings—magical fungi, mysterious dragons and the like. Chinese Ch’an seems to have had little time for such things, Japanese Zen even less and Western Zen less again. And yet that which lies at the heart of our practice is mysterious and unknowable, and perhaps even magical. Contributions (articles, poetry, drawings, calligraphy, songs) exploring the role of magic, mystery and the unknowable, can be sent to: [email protected] by May 17, 2010 Mind Moon Circle is published quarterly by the Sydney Zen Centre, 251 Young Street, Annandale, NSW, 2038, Australia. www.szc.org.au Annual subscription A $28. Printed on recycled paper. DANA: THE WAY TO BEGIN Robert Aitken When someone brings me a flower I vow with all beings to renew my practice of dana, the gift, the way to begin. -

Hiroshima / Tokushima / Kobe Experience

HIROSHIMA / TOKUSHIMA BONUS •View 2 popular World Cultural Heritage sites Days •Experience Whirlpools Cruise ride 7 / KOBE EXPERIENCE Terms & conditions apply Photos © by JNTO MATSUYAMA / EHIME TOKYO Highlights - Aeon Shopping Mall - Ginza HIROSHIMA - Shimanami-Kaido Bridge - Shinjuku - Atomic Bomb Dome Park & - Towel Museum Peace Memorial Park (World Heritage) TOKUSHIMA / KOBE MIYAJIMA / YAMAGUCHI Meals - Tokushima Uzushio Whirlpools Cruise - Hiroshima’s Okonomiyaki - Itsukushima Shrine (World Heritage) - Kobe Mt. Rokko TOKYO - Kintaikyo Bridge - Oyster Meal - Kobe Port Tower - Conger Eel Meal HIROSHIMA - Iwakuni Castle - Mozaic KOBE - Hacchobori - Set / Buffet Dinner SINGAPORE DAY 1 : SINGAPORE NARITA NH 802 0550/1400 DAY 3 : MIYAJIMA / YAMAGUCHI / HIROSHIMA DAY 6 : KOBE-OSAKA ITAMI TOKYO SINGAPORE HANEDA NH 842 1150/2000 (Breakfast / Lunch / Dinner) (Breakfast / Dinner) SINGAPORE HANEDA NH 844 2215/0630 After breakfast, proceed to Miyajima – Itsukushima Shrine After breakfast, it is free at leisure till time to leave for Tokyo. (World Heritage), one of the three most beautiful scenic spots In Tokyo, ample time will be given at Shinjuku or Ikebukuro Assemble at Singapore Changi International Airport Terminal in Japan. It was designed to appear as if floating on the district for sightseeing and shopping. 2 for your flight to Hiroshima via Narita or Haneda. sea and shows the contracts of colors and shapes between Accommodation: the sea and mountains. Visit the beautiful Kintaikyo Bridge, Tokyo Sunshine Prince Hotel or similar. NH 802 HIROSHIMA NH 3237 1740/1930 a five-arched wooden bridge spanning a limpid stream (Breakfast or lunch on board / dinner) and reputed to be the best of Japan’s three most greatest DAY 7 : TOKYO SINGAPORE (Breakfast) Upon arrival at Hiroshima Airport, we will check in hotel for a bridges. -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13