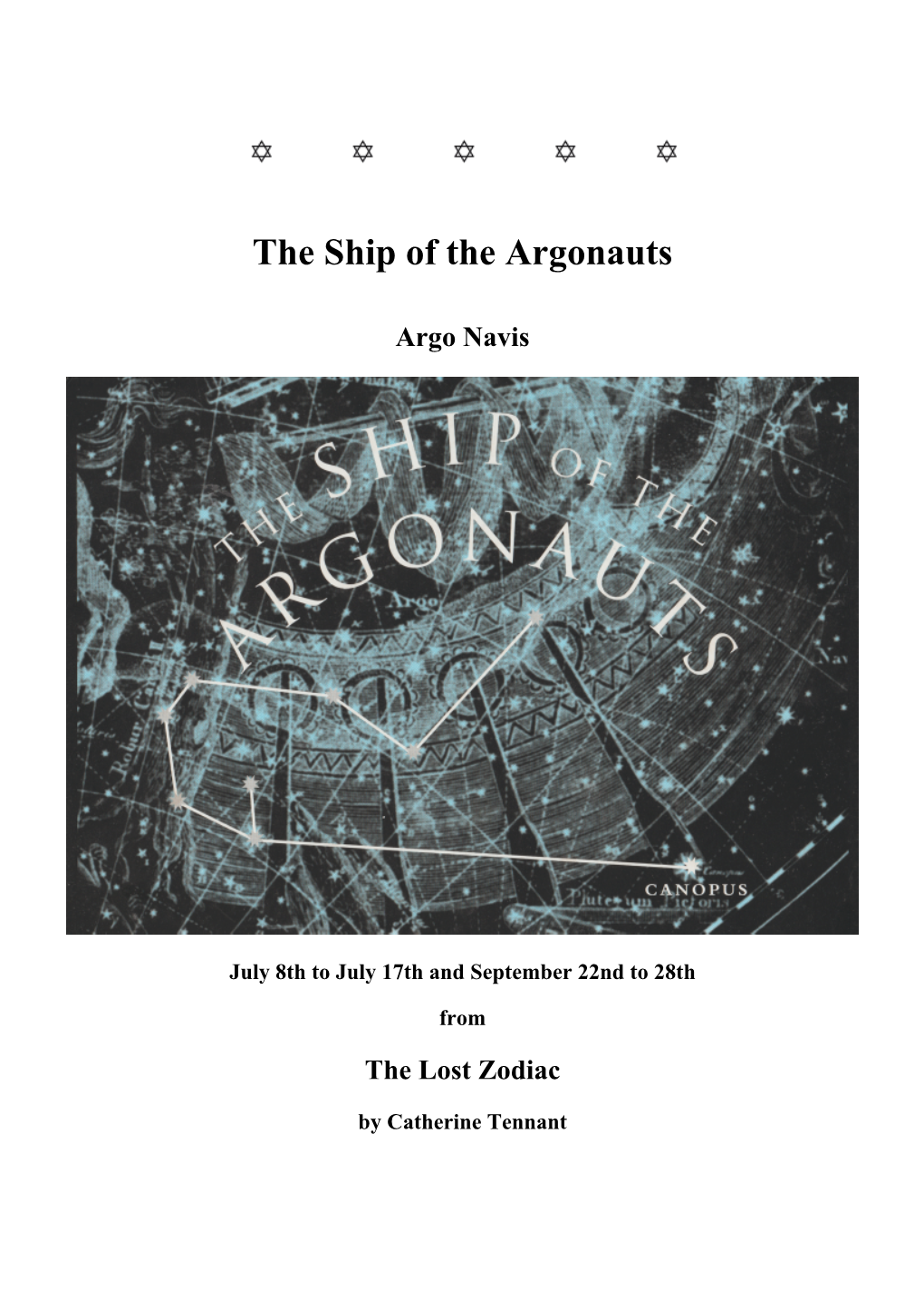

The Ship of the Argonauts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ovid Book 12.30110457.Pdf

METAMORPHOSES GLOSSARY AND INDEX The index that appeared in the print version of this title was intentionally removed from the eBook. Please use the search function on your eReading device to search for terms of interest. For your reference, the terms that ap- pear in the print index are listed below. SINCE THIS index is not intended as a complete mythological dictionary, the explanations given here include only important information not readily available in the text itself. Names in parentheses are alternative Latin names, unless they are preceded by the abbreviation Gr.; Gr. indi- cates the name of the corresponding Greek divinity. The index includes cross-references for all alternative names. ACHAMENIDES. Former follower of Ulysses, rescued by Aeneas ACHELOUS. River god; rival of Hercules for the hand of Deianira ACHILLES. Greek hero of the Trojan War ACIS. Rival of the Cyclops, Polyphemus, for the hand of Galatea ACMON. Follower of Diomedes ACOETES. A faithful devotee of Bacchus ACTAEON ADONIS. Son of Myrrha, by her father Cinyras; loved by Venus AEACUS. King of Aegina; after death he became one of the three judges of the dead in the lower world AEGEUS. King of Athens; father of Theseus AENEAS. Trojan warrior; son of Anchises and Venus; sea-faring survivor of the Trojan War, he eventually landed in Latium, helped found Rome AESACUS. Son of Priam and a nymph AESCULAPIUS (Gr. Asclepius). God of medicine and healing; son of Apollo AESON. Father of Jason; made young again by Medea AGAMEMNON. King of Mycenae; commander-in-chief of the Greek forces in the Trojan War AGLAUROS AJAX. -

Sons and Fathers in the Catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233

Sons and fathers in the catalogue of Argonauts in Apollonius Argonautica 1.23-233 ANNETTE HARDER University of Groningen [email protected] 1. Generations of heroes The Argonautica of Apollonius Rhodius brings emphatically to the attention of its readers the distinction between the generation of the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War in the next genera- tion. Apollonius initially highlights this emphasis in the episode of the Argonauts’ departure, when the baby Achilles is watching them, at AR 1.557-5581 σὺν καί οἱ (sc. Chiron) παράκοιτις ἐπωλένιον φορέουσα | Πηλείδην Ἀχιλῆα, φίλωι δειδίσκετο πατρί (“and with him his wife, hold- ing Peleus’ son Achilles in her arms, showed him to his dear father”)2; he does so again in 4.866-879, which describes Thetis and Achilles as a baby. Accordingly, several scholars have focused on the ways in which 1 — On this marker of the generations see also Klooster 2014, 527. 2 — All translations of Apollonius are by Race 2008. EuGeStA - n°9 - 2019 2 ANNETTE HARDER Apollonius has avoided anachronisms by carefully distinguishing between the Argonauts and the heroes of the Trojan War3. More specifically Jacqueline Klooster (2014, 521-530), in discussing the treatment of time in the Argonautica, distinguishes four periods of time to which Apollonius refers: first, the time before the Argo sailed, from the beginning of the cosmos (featured in the song of Orpheus in AR 1.496-511); second, the time of its sailing (i.e. the time of the epic’s setting); third, the past after the Argo sailed and fourth the present inhab- ited by the narrator (both hinted at by numerous allusions and aitia). -

Caeneus and Heroic (Trans)Masculinity in Ovid's

Caeneus and Heroic (Trans)Masculinity in Ovid’s Metamorphoses Charlotte Northrop Arethusa, Volume 53, Number 1, Winter 2020, pp. 25-41 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/are.2020.0000 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/762106 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] CAENEUS AND HEROIC (TRANS)MASCULINITY IN OVID’S METAMORPHOSES CHARLOTTE NORTHROP Caeneus is a problematic figure among Ovid’s heroes in the Meta- morphoses:1 he aspires to an epic heroism that makes him unique among transgender characters elsewhere in the poem.2 This incongruity forms the basis of the taunts from his centaur opponents. However, instead of just being an aberration among Ovid’s hero characters, Caeneus is actually emblem- atic of the traits that define heroism in the Metamorphoses. Ovid does not shy away from questions of gender identity or generic congruity but makes these questions fundamental to the Caeneus episode and its metatextual relationship with the poem and its poetic tradition. This article argues that Ovid’s treatment of Caeneus is comparable to his treatment of other hero figures, and that his version of Caeneus problematizes the traditional epic relationship between gender identity and genre. Ovid presents a vision of transmasculinity that is innovative when compared with earlier versions of Caeneus and similar mythical figures. His Caeneus narrative is, therefore, a locus for reflection on the nature of heroism within Ovid’s “little Iliad.” To begin, it is necessary to define “transgender” and “transmas- culinity” in terms applicable to Augustan literature. -

The Voyage of the Argo and Other Modes of Travel in Apollonius’ Argonautica

THE VOYAGE OF THE ARGO AND OTHER MODES OF TRAVEL IN APOLLONIUS’ ARGONAUTICA Brian D. McPhee A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: William H. Race James J. O’Hara Emily Baragwanath © 2016 Brian D. McPhee ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Brian D. McPhee: The Voyage of the Argo and Other Modes of Travel in Apollonius’ Argonautica (Under the direction of William H. Race) This thesis analyzes the Argo as a vehicle for travel in Apollonius’ Argonautica: its relative strengths and weaknesses and ultimately its function as the poem’s central mythic paradigm. To establish the context for this assessment, the first section surveys other forms of travel in the poem, arranged in a hierarchy of travel proficiency ranging from divine to heroic to ordinary human mobility. The second section then examines the capabilities of the Argo and its crew in depth, concluding that the ship is situated on the edge between heroic and human travel. The third section confirms this finding by considering passages that implicitly compare the Argo with other modes of travel through juxtaposition. The conclusion follows cues from the narrator in proposing to read the Argo as a mythic paradigm for specifically human travel that functions as a metaphor for a universal and timeless human condition. iii parentibus meis “Finis origine pendet.” iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to my director and mentor, William Race. -

Death and the Female Body in Homer, Vergil, and Ovid

DEATH AND THE FEMALE BODY IN HOMER, VERGIL, AND OVID Katherine De Boer Simons A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Depart- ment of Classics. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Sharon L. James James J. O’Hara William H. Race Alison Keith Laurel Fulkerson © 2016 Katherine De Boer Simons ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT KATHERINE DE BOER SIMONS: Death and the Female Body in Homer, Vergil, and Ovid (Under the direction of Sharon L. James) This study investigates the treatment of women and death in three major epic poems of the classical world: Homer’s Odyssey, Vergil’s Aeneid, and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I rely on recent work in the areas of embodiment and media studies to consider dead and dying female bodies as representations of a sexual politics that figures women as threatening and even mon- strous. I argue that the Odyssey initiates a program of linking female death to women’s sexual status and social class that is recapitulated and intensified by Vergil. Both the Odyssey and the Aeneid punish transgressive women with suffering in death, but Vergil further spectacularizes violent female deaths, narrating them in “carnographic” detail. The Metamorphoses, on the other hand, subverts the Homeric and Vergilian model of female sexuality to present the female body as endangered rather than dangerous, and threatened rather than threatening. In Ovid’s poem, women are overwhelmingly depicted as brutalized victims regardless of their sexual status, and the female body is consistently represented as bloodied in death and twisted in metamorphosis. -

ACHILLES and the CAUCASUS Kevin Tuite1

ACHILLES AND THE CAUCASUS Kevin Tuite1 0. INTRODUCTION. It appears more and more probable that the Proto-Indo-European speech community — or a sizeable component of it, in any event — was in the vicinity of the Caucasus as early as the 4th millenium BCE. According to the most widely-accepted hypothesis and its variants, Proto-Indo- European speakers are to be localized somewhere in the vast lowland region north of the Black and Caspian Seas (Gimbutas 1985, Mallory 1989, Anthony 1991). The competing reconstruction of early Indo-European [IE] migrations proposed by Gamkrelidze and Ivanov (1984) situates the Urheimat to the south of the Caucasus, in eastern Anatolia (see also the interesting attempt to harmonize these two proposals by Sergent 1995). Whichever direction it might have come from, intensive contact between Indo-European speakers and the indigenous Caucasian peoples has left abundant evidence in the languages and cultures of the Caucasus. Numerous lexical correspondences between IE and Kartvelian [South Caucasian] may be due to ancient borrowing (Gamkrelidze and Ivanov 1984: 877-880; Klimov 1991) or perhaps even inheritance from a common ancestral language (Blažek 1992; Manaster-Ramer 1995; Bomhard 1996). The possibility of an “areal and perhaps phylogenetic relation” between IE and the Northwest Caucasian family, suggested by Friedrich (1964) and more recently by Hamp (1989), has been elaborated into a plausible hypothesis through the painstaking work of Colarusso in 1A shorter version of this paper was read at the McGill University Black Sea Conference on 25 January 1996, at the invitation of Dr. John Fossey. I have profited greatly from the advice and encouragement offered by Drs. -

Myth and Reality of Female to Male Sexual Transformation in Classical Antiquity

1 Apostolos L. Pierris Myth and Reality of female to male sexual transformation in Classical Antiquity 2 Plinius ( Historia Naturalis, VII §34) reports four cases in proof of his contention that female-to-male transformation is a reality and no imaginary tale (“ex feminis mutari in maris non est fabulosum”). This is his argument: “Ex feminis mutari in mares non est fabulosum. invenimus in annalibus P. Licinio Crasso C. Cassio Longino cos. Casini puerum factum ex virgine sub parentibus lussuque haruspicum deportatum in insulam desertam. Licinius Mucianus prodidit visum a se Argis Arescontem, cui nomen Arescusae fuisse, nupsisse eliam, mox barbam et virilitatem provenisse uxoremque duxisse; eiusdem sortis et Zmyrnae puerum a se visum. Ipse in Africa vidi mutatum in marem nuptiarum die L. Consitium civem Thysdritanum, <vivevatque cum proderem haec>”. There is a lacuna in the manuscript tradition after “civem Thysdritanum”. Mayhoff (the Teubner editor) correctly supplies the last clause to complete the sentence from Aulus Gellius, who quotes verbatim Plinus’ passage as we shall see. [Change from women to men is no fabulous tale. We find in the Annals under the consulship of P. Licinius Crassus and C. Cassius Longinus that a virgin in Casinum, still under the tutelship of her parents, became a boy, who on the command of the soothsayers was deported to a desert island. Licinius Mucianus recorded that he saw in Argos Arescon, whose name previously was Arescousa, she having even been married, then soon thereupon beard and virility had arisen, and he took a wife. Of the same lot was a boy seen by him in Smyrna. -

Divine Riddles: a Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014

Divine Riddles: A Sourcebook for Greek and Roman Mythology March, 2014 E. Edward Garvin, Editor What follows is a collection of excerpts from Greek literary sources in translation. The intent is to give students an overview of Greek mythology as expressed by the Greeks themselves. But any such collection is inherently flawed: the process of selection and abridgement produces a falsehood because both the narrative and meta-narrative are destroyed when the continuity of the composition is interrupted. Nevertheless, this seems the most expedient way to expose students to a wide range of primary source information. I have tried to keep my voice out of it as much as possible and will intervene as editor (in this Times New Roman font) only to give background or exegesis to the text. All of the texts in Goudy Old Style are excerpts from Greek or Latin texts (primary sources) that have been translated into English. Ancient Texts In the field of Classics, we refer to texts by Author, name of the book, book number, chapter number and line number.1 Every text, regardless of language, uses the same numbering system. Homer’s Iliad, for example, is divided into 24 books and the lines in each book are numbered. Hesiod’s Theogony is much shorter so no book divisions are necessary but the lines are numbered. Below is an example from Homer’s Iliad, Book One, showing the English translation on the left and the Greek original on the right. When citing this text we might say that Achilles is first mentioned by Homer in Iliad 1.7 (i.7 is also acceptable). -

Greek Mythology Link (Complete Collection)

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • Español • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. This PDF contains portions of the Greek Mythology Link COMPLETE COLLECTION, version 0906. In this sample most links will not work. THE COMPLETE GREEK MYTHOLOGY LINK COLLECTION (digital edition) includes: 1. Two fully linked, bookmarked, and easy to print PDF files (1809 A4 pages), including: a. The full version of the Genealogical Guide (not on line) and every page-numbered docu- ment detailed in the Contents. b. 119 Charts (genealogical and contextual) and 5 Maps. 2. Thousands of images organized in albums are included in this package. The contents of this sample is copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. To buy this collection, visit Editions. Greek Mythology Link Contents The Greek Mythology Link is a collection of myths retold by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology, published in 1993 (available at Amazon). The mythical accounts are based exclusively on ancient sources. Address: www.maicar.com About, Email. Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. ISBN 978-91-976473-9-7 Contents VIII Divinities 1476 Major Divinities 1477 Page Immortals 1480 I Abbreviations 2 Other deities 1486 II Dictionaries 4 IX Miscellanea Genealogical Guide (6520 entries) 5 Three Main Ancestors 1489 Geographical Reference (1184) 500 Robe & Necklace of -

Gender Transformation and Ontology in Ovid's Metamorphoses

Philomathes Gender Transformation and Ontology in Ovid's Metamorphoses pisodes of gender transformation in Ovid’s Metamorphoses Eprimarily reflect and reinforce traditional Roman binary gender roles, misogyny, and normative sexuality. These hegemonic ideologies are visible in the motivations for each metamorphosis, wherein masculinization is framed as a miracle performed on a willing subject and feminization as a horrific and unnatural curse born from the perverted desires of an assailant. Yet a close analysis of these narratives reveals a crucial point of difference between Ovid’s assumptions about gender and that of most modern Westerners: for Ovid, gender is at least hypothetically mutable. It is generally synonymous with sex (although even this is complicated in the story of Iphis), but once a person’s sex has been physically changed, they can and should take up their new social role and be accepted as a member of their new gender. In this essay, I will examine three cases of gender transformation from the Metamorphoses – the stories of Caeneus, Iphis, and Hermaphroditus and Salmacis – from a queer and specifically transgender perspective which seeks to reveal the underlying ontology of Ovid’s conception of gender. I argue that although these stories reflect the hegemonic gender ideologies of the period, they still illustrate conceptions of gender that differ radically from the biologically determinist and immutable one that is hegemonic in modern Western culture, making the Metamorphoses a highly significant text for queer scholarship. 54 Philomathes The story of Caeneus (Met. 12.146-535)1 defines vulnerability to sexual violence as a fundamental characteristic of womanhood. -

An Intertextual Approach to Problems of Genre and Heroism in Statius’ Achilleid

Appropriate Transgressions: An Intertextual Approach to Problems of Genre and Heroism in Statius’ Achilleid By Hanna Z. C. Mason A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Classics Victoria University of Wellington 2013 Abstract Statius’ second epic poem, the Achilleid, deals with a subject matter that is particularly problematic: Achilles’ early life, in which he is raised by a centaur in the wilderness and then disguises himself as a woman in order to rape the princess of Scyros. Recent scholarship has also pointed to other problematic elements, such as Achilles’ troublesome relationship with his mother or the epic’s intertextual engagement with elegiac and ‘un-epic’ poetry. This thesis extends such scholarship by analysing Statius’ use of transgression in particular. It focuses primarily upon the heroic character of Achilles and the generic program of the Achilleid as a whole. The first chapter focuses upon Achilles’ childhood and early youth as a foster child and student of the centaur Chiron. It demonstrates that the hero’s upbringing is used to emphasise his ambiguous nature in line with the Homeric Iliad, as a hero who is capable of acting appropriately, but chooses not to. Achilles’ wild and bestial nature is emphasised by its difference to the half-human character of Chiron, who might be expected to be act like an animal, but instead becomes an example of civilisation overcoming innate savagery, an example of what Achilles could have been. The second chapter discusses the ambiguities inherent in a study of transgression, in the light of Achilles’ transvestite episode on Scyros. -

Pseudo-Apollodoros' Bibliotheke and the Greek Mythological Tradition

Pseudo-Apollodoros’Bibliotheke and the Greek Mythological Tradition by Evangelia Kylintirea A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Classics University College London May 2002 ProQuest Number: 10014985 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10014985 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract Pseudo-Apollodoros’ Bibliotheke is undeniably the most useful single source for the mythical tradition of Greece. Enclosing in a short space a remarkable quantity of information, it offers concise and comprehensive accounts of most of the myths that had come to matter beyond local boundaries, providing its readers with their most popular variants. This study concentrates on the most familiar stories contained in the first book of the Bibliotheke and their proper place in the overall structure of Greek mythology. Chapter One is dedicated to the backbone of Apollodoros’ work: the chronological organisation of Greek mythical history in genealogies. It discusses the author’s individual plan in the arrangement and presentation of his material and his conscious striving for cohesion.