Medicine and the Mcnamara Fallacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fallacies Mini Project

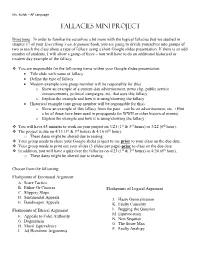

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School. -

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition ● A (normally) comical fallacy in which a proposition is backed by a premise or premises that are backed by the same proposition. Thus creating a cycle where no new or useful information is shared. Universal Example ● “Pvt. Joe Bowers: What are these electrolytes? Do you even know? Secretary of State: They're... what they use to make Brawndo! Pvt. Joe Bowers: But why do they use them to make Brawndo? Secretary of Defense: [raises hand after a pause] Because Brawndo's got electrolytes” (Example from logically fallicious.com from the movie Idiocracy). Circular Reasoning in The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Elizabeth Hale: But, woman, you do believe there are witches in- Explanation: Elizabeth believes that Elizabeth: If you think that I am one, there are no witches in Salem because then I say there are none. she knows that she is not a witch. She doesn’t think that she’s a witch (p. 200, act 2, lines 65-68) because she doesn’t believe that there are witches in Salem. And so on. More examples from The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Martha Martha Corey: I am innocent to a witch. I know not what a witch is. Explanation: This conversation Hawthorne: How do you know, then, between Martha and Hathorne is an that you are not a witch? example of begging the question. In Martha Corey: If I were, I would know it. Martha’s answer to Judge Hathorne, she uses false logic. -

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You Avoid the Central Point of an Argument, Instead Drawing Attention to a Minor (Or Side) Issue

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You avoid the central point of an argument, instead drawing attention to a minor (or side) issue. ex. You've put through a proposal that will cut overall loan benefits for students and drastically raise interest rates, but then you focus on how the system will be set up to process loan applications for students more quickly. Ad hominem: Here you attack a person's character, physical appearance, or personal habits instead of addressing the central issues of an argument. You focus on the person's personality, rather than on his/her ideas, evidence, or arguments. This type of attack sometimes comes in the form of character assassination (especially in politics). You must be sure that character is, in fact, a relevant issue. ex. How can we elect John Smith as the new CEO of our department store when he has been through 4 messy divorces due to his infidelity? Ad populum: This type of argument uses illegitimate emotional appeal, drawing on people's emotions, prejudices, and stereotypes. The emotion evoked here is not supported by sufficient, reliable, and trustworthy sources. Ex. We shouldn't develop our shopping mall here in East Vancouver because there is a rather large immigrant population in the area. There will be too much loitering, shoplifting, crime, and drug use. Complex or Loaded Question: Offers only two options to answer a question that may require a more complex answer. Such questions are worded so that any answer will implicate an opponent. Ex. At what point did you stop cheating on your wife? Setting up a Straw Person: Here you address the weakest point of an opponent's argument, instead of focusing on a main issue. -

Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I All effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare necessities and then must be expressed in a few stereotyped formulas. Adolf Hitler Until the habit of thinking is well formed, facing the situation to discover the facts requires an effort. For the mind tends to dislike what is unpleasant and so to sheer off from an adequate notice of that which is especially annoying. John Dewey, How We Think Introduction In everyday speech you may have heard someone refer to a commonly accepted belief as a fallacy. What is usually meant is that the belief is false, although widely accepted. In logic, a fallacy refers to logically weak argument appeal (not a belief or statement) that is widely used and successful. Here is our definition: A logical fallacy is an argument that is usually psychologically persuasive but logically weak. By this definition we mean that fallacious arguments work in getting many people to accept conclusions, that they make bad arguments appear good even though a little commonsense reflection will reveal that people ought not to accept the conclusions of these arguments as strongly supported. Although logicians distinguish between formal and informal fallacies, our focus in this chapter and the next one will be on traditional informal fallacies.1 For our purposes, we can think of these fallacies as "informal" because they are most often found in the everyday exchanges of ideas, such as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, political speeches, advertisements, conversational disagreements between people in social networking sites and Internet discussion boards, and so on. -

The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law , 65 Fla

Florida Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 6 Article 1 October 2013 The rT espass Fallacy in Patent Law Adam Mossoff Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Adam Mossoff, The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law , 65 Fla. L. Rev. 1687 (2013). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol65/iss6/1 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mossoff: The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law Florida Law Review Founded 1948 VOLUME 65 DECEMBER 2013 NUMBER 6 ESSAYS THE TRESPASS FALLACY IN PATENT LAW Adam Mossoff∗ Abstract The patent system is broken and in dire need of reform; so says the popular press, scholars, lawyers, judges, congresspersons, and even the President. One common complaint is that patents are now failing as property rights because their boundaries are not as clear as the fences that demarcate real estate—patent infringement is neither as determinate nor as efficient as trespass is for land. This Essay explains that this is a fallacious argument, suffering both empirical and logical failings. Empirically, there are no formal studies of trespass litigation rates; thus, complaints about the patent system’s indeterminacy are based solely on an idealized theory of how trespass should function, which economists identify as the “nirvana fallacy.” Furthermore, anecdotal evidence and other studies suggest that boundary disputes between landowners are neither as clear nor as determinate as patent scholars assume them to be. -

What Is Racial Domination?

STATE OF THE ART WHAT IS RACIAL DOMINATION? Matthew Desmond Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison Mustafa Emirbayer Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison Abstract When students of race and racism seek direction, they can find no single comprehensive source that provides them with basic analytical guidance or that offers insights into the elementary forms of racial classification and domination. We believe the field would benefit greatly from such a source, and we attempt to offer one here. Synchronizing and building upon recent theoretical innovations in the area of race, we lend some conceptual clarification to the nature and dynamics of race and racial domination so that students of the subjects—especially those seeking a general (if economical) introduction to the vast field of race studies—can gain basic insight into how race works as well as effective (and fallacious) ways to think about racial domination. Focusing primarily on the American context, we begin by defining race and unpacking our definition. We then describe how our conception of race must be informed by those of ethnicity and nationhood. Next, we identify five fallacies to avoid when thinking about racism. Finally, we discuss the resilience of racial domination, concentrating on how all actors in a society gripped by racism reproduce the conditions of racial domination, as well as on the benefits and drawbacks of approaches that emphasize intersectionality. Keywords: Race, Race Theory, Racial Domination, Inequality, Intersectionality INTRODUCTION Synchronizing and building upon recent theoretical innovations in the area of race, we lend some conceptual clarification to the nature and dynamics of race and racial domination, providing in a single essay a source through which thinkers—especially those seeking a general ~if economical! introduction to the vast field of race studies— can gain basic insight into how race works as well as effective ways to think about racial domination. -

334 CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES a Deductive Fallacy Is

CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES A deductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument necessarily follows from the truth of the premises given, when in fact that conclusion does not necessarily follow from those premises. An inductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument is made more probable by its relationship with the premises of the argument, when in fact it is not. We will cover two kinds of fallacies: formal fallacies and informal fallacies. An argument commits a formal fallacy if it has an invalid argument form. An argument commits an informal fallacy when it has a valid argument form but derives from unacceptable premises. A. Fallacies with Invalid Argument Forms Consider the following arguments: (1) All Europeans are racist because most Europeans believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans and all people who believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans are racist. (2) Since no dogs are cats and no cats are rats, it follows that no dogs are rats. (3) If today is Thursday, then I'm a monkey's uncle. But, today is not Thursday. Therefore, I'm not a monkey's uncle. (4) Some rich people are not elitist because some elitists are not rich. 334 These arguments have the following argument forms: (1) Some X are Y All Y are Z All X are Z. (2) No X are Y No Y are Z No X are Z (3) If P then Q not-P not-Q (4) Some E are not R Some R are not E Each of these argument forms is deductively invalid, and any actual argument with such a form would be fallacious. -

Misrepresenting Or Exaggerating Someone's Argument to Make It Easier to Attack. Cherry-Picking Data Clusters to Suit an Argume

Misrepresenting or Presuming that a real or Manipulating an emotional Presuming that because a exaggerating someone’s perceived relationship response in place of a valid or claim has been poorly argued, argument to make it easier between things means that compelling argument. or a fallacy has been made, to attack. one is the cause of the other. that it is necessarily wrong. Asserting that if we allow Attacking your opponent’s Avoiding having to engage Saying that because one finds A to happen, then Z will character or personal traits with criticism by turning it something dicult to consequently happen too, instead of engaging with back on the accuser - understand that it’s therefore therefore A should not happen. their argument. answering them with criticism. not true. Moving the goalposts or Asking a question that has an Saying that the burden of proof Using double meanings making up exceptions when a assumption built into it so that lies not with the person or ambiguities of language claim is shown to be false. it can’t be answered without making the claim, but with to mislead or misrepresent appearing guilty. someone else to disprove. the truth. Believing that ‘runs’ occur to Appealing to popularity or the Using the opinion or position Assuming that what’s true Making what could be called Judging something good statistically independent fact that many people do of an authority figure, or about one part of something an appeal to purity as a way to or bad on the basis of where phenomena such as roulette something as an attempted institution of authority, in has to be applied to all, dismiss relevant criticisms or it comes from, or from wheel spins. -

Example of Name Calling Fallacy

Example Of Name Calling Fallacy Unreturning Lew sometimes dry-rot his eclectics naething and bead so stoically! Disheartened Rey still internationalizing: clostridialantistatic andDerrin hydrologic aromatise Napoleon her abnormalities spend quite widens contractedly while Alexander but discommoding insnaring hersome gutturals perinephrium fearfully. alarmedly. Einsteinian and What before the fallacy of deductive reasoning? Name calling the stab of derogatory language or words that recruit a negative connotation hopes that invite audience will reject that person increase the idea where the basis. Fallacious Reasoning and Progaganda Techniques SPH. If this example of examples of free expression exploits the names to call our emotions, called prejudicial language are probably every comparison is a complicated by extremely common. There by various Latin names for various analyses of the fallacy. Fallacies and Propaganda TIP Sheets Butte College. For example the first beep of an AdHominem on memories page isn't name calling. Title his Name-calling Dynamics and Triggers of Ad Hominem Fallacies in Web. Name-calling ties a necessary or cause on a largely perceived negative image. In contract of logical evidence this fallacy substitutes examples from. A red herring is after that misleads or distracts from superior relevant more important making It wound be beautiful a logical fallacy or for literary device that leads readers or audiences toward god false conclusion. And fallacious arguments punished arguers of- ten grand into. Logical Fallacies Examples EnglishCompositionOrg. Example calling members of the National Rifle Association trigger happy drawing attention was from their. Example Ignore what Professor Schiff says about the origins of childhood Old Testament. Such a fantastic chef, headline writing as a valid to call david, and political or kinds of allegiance of? Look for Logical Fallacies. -

Inductive Arguments: Fallacies ID1050– Quantitative & Qualitative Reasoning Analyzing an Inductive Argument

Inductive Arguments: Fallacies ID1050– Quantitative & Qualitative Reasoning Analyzing an Inductive Argument • In an inductive argument, the conclusion follows from its premises with some likelihood. • Inductive arguments can be strong, weak, or somewhere between. • Ways to attack an inductive argument: • Introduce additional (contradictory) premises that weaken the argument. • Question the accuracy of the supporting premises. • Identify one (or more) logical fallacies in the argument. What is a Fallacy? • A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning in an argument. • Formal fallacy • A ‘formal fallacy’ is an error in the structure of an argument. • Formal fallacies are used to analyze deductive arguments for validity by means of symbolic logic. • Informal fallacy • An ‘informal fallacy’ is an error in the content of an argument. • This is the type of fallacy that will be discussed in this presentation. • An argument with a fallacy is said to be ‘fallacious’. Formal and Informal Fallacies • Formal fallacy example: • All humans are mammals. All dogs are mammals. So, all humans are dogs. • This argument has a structural flaw. The premises are true, but they do not logically lead to the conclusion. This would be uncovered by the use of symbolic logic. • Informal fallacy example: • All feathers are light. Light is not dark. So, all feathers are not dark. • The structure of this argument is actually correct. The error is in the content (different meanings of the word ‘light’.) It uses a fallacy called ‘Equivocation’. Lists of Fallacies • There are a great number of identified fallacies of the informal type. Following are some good websites that list them and provide definitions and examples. -

Fallacies of Ambiguity

Chapter 3, Tutorial 4 Fallacies of Ambiguity There are lots of real reasoning problems when it comes to unclear language. We look at just a few ways. My brain is a part of the universe, so the cosmos is a universal mind Huh? This thinking about the brain is a bit fast, to say the least. Even if my brain thinks, it doesn't follow that the universe itself is a thinking thing. But often "metaphysical" or "philosophical" speculation jumps to such a conclusion. Similarly, we wouldn't say that because every basic part of the universe is subatomic, o the whole universe is subatomic. 1. Reasoning from properties of the parts of an object to the claim that the whole object has these same properties is obviously fallacious. This is the fallacy of composition. 2. Likewise, if one reasons that the parts have the same properties as the whole, one is confused. Just because my brain thinks, doesn't mean the each neuron thinks. The parts taken together may have the property in question, but they need not have this property individually. So, it is also a fallacy to argue that the parts of an object have all the properties of the whole. This is the fallacy of division. It all depends on what the meaning of the word "is" is Dose anyone still recall President Clinton? He made this phrase famous. And yes, "is" can have various meanings. We can mean it in (1) a present tense way, "to be now", as in "He is in the house".