Depictions of Koreans in American Literature”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhetorical Readings of Asian American Literacy Narratives

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ARTICULATING IDENTITIES: RHETORICAL READINGS OF ASIAN AMERICAN LITERACY NARRATIVES Linnea Marie Hasegawa, Doctor of Philosophy, 2004 Dissertation directed by: Professor Kandice Chuh Department of English This dissertation examines how Asian American writers, through what I call critical acts of literacy, discursively (re)construct the self and make claims for alternative spaces in which to articulate their identities as legitimate national subjects. I argue that using literacy as an analytic for studying certain Asian American texts directs attention to the rhetorical features of those texts thereby illuminating how authors challenge hegemonic ideologies about literacy and national identity. Analyzing the audiences and situations of these texts enriches our understanding of Asian American identity formation and the social, cultural, and political functions that these literacy narratives serve for both the authors and readers of the texts. The introduction lays the groundwork for my dissertation’s arguments and method of analysis through a reading of Theresa Cha’s Dictée. By situating readers in such a way that they are compelled to consider their own engagements with literacy and how discourses of literacy and citizenship function to reproduce dominant ideologies, Dictée advances a theoretical model for reading literacy narratives. In subsequent chapters I show how this methodology encourages a kind of reading practice that may serve to transform readers’ ideologies. Part I argues that reading the fictional autobiographies of Younghill Kang and Carlos Bulosan as literacy narratives illuminates the ways in which they simultaneously critique the contradiction between the myth of American democratic inclusion and the reality of exclusion while claiming Americanness through a demonstration of their own and their fictional alter egos’ literacies. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Diasporic Ethnopoetics Through “Han-Gook”: An Inquiry into Korean American Technicians of the Enigmatic A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by David Hur Committee in charge: Professor Yunte Huang, co-Chair Professor Stephanie Batiste, co-Chair Professor erin Khuê Ninh Professor Sowon Park September 2020 The dissertation of David Hur is approved. ____________________________________________ erin Khuê Ninh ____________________________________________ Sowon Park ____________________________________________ Stephanie Batiste, Committee Co-Chair ____________________________________________ Yunte Huang, Committee Co-Chair September 2020 Diasporic Ethnopoetics Through “Han-Gook”: An Inquiry into Korean American Technicians of the Enigmatic Copyright © 2020 by David Hur iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey has been made possible with support from faculty and staff of both the Comparative Literature program and the Department of Asian American Studies. Special thanks to Catherine Nesci for providing safe passage. I would not have had the opportunities for utter trial and error without the unwavering support of my committee. Thanks to Yunte Huang, for sharing poetry in forms of life. Thanks to Stephanie Batiste, for sharing life in forms of poetry. Thanks to erin Khuê Ninh, for sharing countless virtuous lessons. And many thanks to Sowon Park, for sharing in the witnessing. Thirdly, much has been managed with a little -

Younghill Kang's East Goes West

EURAMERICA Vol. 43, No. 4 (December 2013), 753-783 © Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica http://euramerica.org Asian American Model Masculinities —Younghill Kang’s East Goes West: The Making of an Oriental Yankee Karen Kuo Asian Pacific American Studies and the School of Social Transformation Arizona State University P.O. Box 876403, Tempe, Arizona, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This essay presents a comparative racial and gender analysis of masculinity and power during the post- Depression United States in a reading of Younghill Kang’s novel, East Goes West: The Making of an Oriental Yankee.1 I argue that Kang’s novel, primarily read as an immigrant story yields insight into the multiple racial and class formations of Asian and black men in the U.S. within the context of sexuality, power, labor, and the economy. Kang’s novel shows how the dominant racial paradigm of black versus white in the U.S. depends on an Asian male subject who negotiates his racialized identity within a tripartite racial system of black, white, and Asian. This racial negotiation of Asian masculinity revolves around the figure of the early Asian foreign student who receives privileges Received March 31, 2009; accepted June 5, 2013; last revised July 28, 2013 Proofreaders: Kuei-feng Hu, Chih-wei Wu, Chia-Chi Tseng 1 The first edition of the novel was published in 1937 but for the purposes of this essay, I will be referencing the 1997 edition published by Kaya Press. 754 EURAMERICA and favors by white elites and intellectuals. -

Multiracial Korean American Subject Formation Along the Black-White Binary

THE MILITARY CAMPTOWN IN RETROSPECT: MULTIRACIAL KOREAN AMERICAN SUBJECT FORMATION ALONG THE BLACK-WHITE BINARY Perry Dal-nim Miller A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2007 Committee: Khani Begum, Advisor Rekha Mirchandani ii ABSTRACT Khani Begum, Advisor This thesis applies theoretical approaches from the sociology of literature and Asian Americanist critique to a study of two novels by multiracial Korean American authors. I investigate themes of multiracial identity and consumption in Heinz Insu Fenkl’s Memories of My Ghost Brother and Nora Okja Keller’s Fox Girl, both set in the 1960’s and 1970’s gijichon or military camptown geography, recreational institutions established around U.S. military installations in the Republic of Korea. I trace the literary production of Korean American subjectivity along a socially constructed dichotomy of blackness and whiteness, examining the novels’ representations of cross-racial interactions in a camptown economy based on the militarized sexual labor of working-class Korean women. I conclude that Black-White binarisms are reproduced in the gijichon through the consumption practices of both American military personnel and Korean gijichon workers, and that retrospective fictional accounts of gijichon multiraciality signal a shift in artistic, scholarly, and popular conceptualizations of Korean American and Asian American group identities. iii To my father iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis coalesced with the guidance and support of many people. I am deeply thankful to the members of my thesis committee, Professor Khani Begum and Professor Rekha Mirchandani. Their expert direction, patience, and support taught me to strive toward intellectual and human growth. -

Younghill Kang and Richard Wright by Byung Sun Yu a Dissertation

America(s) in Early Twentieth Century Ethnic Minority Writing: Younghill Kang and Richard Wright By Byung Sun Yu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Elaine Kim, Chair Professor Sau-ling Wong Professor Marcial González Fall 2013 ABSTRACT America(s) in Early Twentieth Century Ethnic Minority Writing: Younghill Kang and Richard Wright by Byung Sun Yu Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Elaine Kim, Chair In this dissertation, I explore the meanings of “America(s)” in the fictional works by early twentieth century ethnic minority writers—Younghill Kang and Richard Wright. They reveal the heterogeneity of America as opposed to the myth of America as a singular formation. I attempt to approach American racialized ethnic minority literature comparatively, to avoid the limitations of focusing on writers of one background. Comparative approaches account for the particular social, cultural, historical, political, and geographical contingencies of different ethnic groups. In the first chapter on Younghill Kang’s East Goes West, I argue that America is a reified society, which is very different from the society Kang has dreamed for a long time. Analyzing Kang’s autobiographical novel East Goes West, I employ the theoretical frame of “reification” to explore the social structure that prevents Han, Kang’s alter ego, from being accepted as an American no matter how ardently he wishes for acceptance. I argue that though he criticizes a reified American society such as rationalization, quantification, and objectification, his criticism of the society is based on an anachronistic organic romanticism. -

The Pathos of Temporality in Mid-20Th Century Asian American Fiction

THE PATHOS OF TEMPORALITY IN MID-20TH CENTURY ASIAN AMERICAN FICTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH by Sarah C. Gardam May 2018 Examining Committee Members: Sue-Im Lee, Advisory Chair, English Department Sheldon Brivic, English Department Alan Singer, English Department Laura Levitt, Religion Department ii ABSTRACT Lack of understanding regarding the role that temporality-pathos plays in Asian American literature leads scholars to misread many textual passages as deviations from the implied authors’ political critiques. This dissertation invites scholars to recognize temporality-focused passages in Younghill Kang’s East Goes West, Carlos Bulosan’s America is in the Heart, and John Okada’s No-No Boy, as part of a pathos formula developed by avant-garde Asian American writers to resist systemic alienations experienced by Asian Americans by diagnosing and treating America’s empathy gap. I find that each of pathae examined – the pathos of finitude, the pathos of idealism, and the pathos of confusion – appears in each of the major primary texts discussed, and that these pathae not only invite similitude-based empathy from a wide readership, but also prompt, via multiple methods, the expansion of empathy. First, the authors use these pathae diagnostically: the pathos of finitude makes visible American imperialism’s destruction of prior ways of life; the pathos of idealism exposes the falsity of the futures promised by liberalism; and the pathos of confusion counters the destructive nationalisms that fractured the era. Second, the authors use these temporality pathae to identify the instrumentalist reasoning underlying these capitalist ideologies and to show how they stunt American empathy. -

The Inflow of Western Knowledge and the Process of Internalization: Comparison of the Grass Roof and Der Yalu Fliesst

The Inflow of Western Knowledge and the Process of Internalization: Comparison of The Grass Roof and Der Yalu Fliesst Lim Seon-ae The purpose of this study is to ascertain the differences between the inflow of Western knowledge and the process of its internalization as seen in The Grass Roof (Younghill Kang 1931) and Der Yalu Fliesst (Mirok Li 1946). These two works were considered leaders for a long time because they were published in English and German. The main point of this work, which is internalization and the acquirement of Western knowledge, is to show the differences among people, especially the difference between Younghill Kang’s Han Chungpa and Mirok Li’s narrator of Li Mirok. These two characters show the differences in comprehension of Western education, learning methods of Western knowledge, and the process of looking at the West. Their acts cause another kind of colonialism which is ironic and they are crit- icized as strengthening Orientalism in the West. But at the point that we over- came the obstacle of human species and languages, Younghill Kang’s and Mirok Li’s works should be acknowledged that they informed about modern Korea which disappeared by the over-use of foreign languages. They were the writers who showed that the nation was alive although their country was broken. Keywords : Younghill Kang, Mirok Li, The Grass Roof, Der Yalu Fliesst, western knowledge, traditional knowledge, internalization, reorganization of knowledge The Review of Korean Studies Volume 10 Number 1 (March 2007) : 91-104 © 2007 by the Academy of Korean Studies. All rights reserved. -

Korean American Matters and Identity

KOREAN AMERICAN MATTERS AND IDENTITY IN KOREAN AMERICAN NOVELS by SEUNG-WON KIM Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON DECEMBER 2011 Copyright © by Seung-Won Kim 2011 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with great pleasure and a sense of accomplishment that I compose this page. During my pursuit of a Doctorate of Philosophy, I struggled very hard to adjust not only to the demands of graduate classes but also to living in a totally foreign culture. First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to my Maker, for without His wisdom, spiritual strength, grace, and favor I would not have made a progress or accomplished my dream of obtaining a Ph.D degree. Next, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my doctoral committee members for providing me with a scholarly help as well as personal and emotional advice throughout the years. Special thanks go to my committee chair, Dr. Tim Morris. From my first semester to the present, he has encouraged and guided me and has shown me enduring patience. He has a sincere zeal for knowledge, is highly devoted to his students, and embodies the model of a true scholar, mentor, and friend. I also would like to thank Dr. Joanna Johnson who encouraged and guided me in constructing my own vision for children’s literature during the preparation of this writing project. I also would like to thank Dr. -

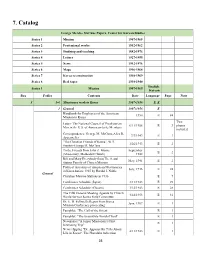

George Mcafee Mccune Paper Finding Aid Part 2 09012020

7. Catalog George McAfee McCune Papers, Center for Korean Studies Series 1 Mission 1907-1965 Series 2 Professional works 1932-1962 Series 3 Studying and teaching 1882-1976 Series 4 Letters 1927-1955 Series 5 News 1932-1976 Series 6 Maps 1916-1968 Series 7 Korea reconstruction 1938-1969 Series 8 Reel tapes 1938-1940 English, Series 1 Mission 1907-1965 Korean Box Fodler Contents Date Language Page Note 5 1-6 Missionary work in Korea 1907-1956 E, K 1 General 1907-1956 E Handbook for Employees of the American 1950 E 84 Mission in Korea Two Letter: The National Council of Presbyterian 6/11/1956 E 3 photos Men in the U.S. of American-to its Members included Correspondence: George M. McCune-Alice R. 7/3/1942 E 2 Appenzeller "The Christian Friends of Korea", W.T. 1/26/1943 E 2 Stanton-George M. McCune To the Friends from John Z. Moore September E 2 (Missionary, Methodist Church) , 1942 Bill and Mary Everybody from The Seoul May, 1941 E 2 Station Family of Chosen Mission Political Activities of American Missionaries July, 1936 E 24 in Korea before 1905 by Harold J. Noble General Christian Mission Stations in 1936 · E 7 Conference Schedule (Japan) 3/11/1943 E 29 Conference Schedule (Chosen) 3/12/1943 E 28 The Fifth General Meeting Agenda by Church 4/22/1953 E 31 World Service Korea Field Committee Dr. E. D. Follwell's Report from Korea June, 1907 E 1 Mission Conference proceeding Pamphlet: "The Call of the Orient · E 1 Pamphlet: "The Irresistible Word of God" · E 1 Newspaper "A Junior Missionary's First · E 1 Itinerating Trip" News clipping "Dr. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Korean-American Literature as Autobiographical Metafiction: Focusing on the Protagonist’s “Writer” Identity in East Goes West, Dictee, and Native Speaker. A dissertation submitted to the Division of Graduate Education and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of English of the College of Arts and Sciences 2008 By Ha Young Choi B.A. (KonKuk University, Seoul) 1997 M.A.(KonKuk University, Seoul) 1999 Abstract This dissertation employs “metafiction” as a perspective to reread Asian- American texts across the realist-postmodern divide, exploring subversive junctions the texts in question betray. This dissertation rereads three Korean-American literary texts with autobiographical or autofictional elements as a complementary move to critical debates between Lisa Lowe and Jinqi Ling on realism and postmodernism in Asian- American literature. Considering the works are autobiographical or autofictional, I read each of the works as a metafiction in which a writer (author) writes about a writer (protagonist) writing a work (text) a reader reads now. In this never-ending self-reflexive structure, I observe some points where an authorial self encounters /conflicts with fictional self, and explore how their encounter /conflict creates a rupture on the ideologically defined smooth surface of Asian-American “writer” identity, which has been often overshadowed by their Asian American identity. -

A History of the Canadian Missionaries and Korean Protestants in Northern Korea and Manchuria, 1893 - 1928

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018-09-12 Dispatches from the Wilderness: A History of the Canadian Missionaries and Korean Protestants in Northern Korea and Manchuria, 1893 - 1928 Glover, Frederick James Glover, F. J. (2018). Dispatches from the Wilderness: A History of the Canadian Missionaries and Korean Protestants in Northern Korea and Manchuria, 1893 - 1928 (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/32960 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/107797 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Dispatches from the Wilderness: A History of the Canadian Missionaries and Korean Protestants in Northern Korea and Manchuria, 1893 - 1928 by Frederick James Glover A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2018 © Frederick James Glover 2018 Abstract This thesis examines the motivations of the Canadian missionaries and Korean Protestants in Hamgyeong Province (Northeastern Korea) -

Younghill Kang and Richard Wright by Byung Sun Yu A

America(s) in Early Twentieth Century Ethnic Minority Writing: Younghill Kang and Richard Wright By Byung Sun Yu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Elaine Kim, Chair Professor Sau-ling Wong Professor Marcial González Fall 2013 ABSTRACT America(s) in Early Twentieth Century Ethnic Minority Writing: Younghill Kang and Richard Wright by Byung Sun Yu Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Elaine Kim, Chair In this dissertation, I explore the meanings of “America(s)” in the fictional works by early twentieth century ethnic minority writers—Younghill Kang and Richard Wright. They reveal the heterogeneity of America as opposed to the myth of America as a singular formation. I attempt to approach American racialized ethnic minority literature comparatively, to avoid the limitations of focusing on writers of one background. Comparative approaches account for the particular social, cultural, historical, political, and geographical contingencies of different ethnic groups. In the first chapter on Younghill Kang’s East Goes West, I argue that America is a reified society, which is very different from the society Kang has dreamed for a long time. Analyzing Kang’s autobiographical novel East Goes West, I employ the theoretical frame of “reification” to explore the social structure that prevents Han, Kang’s alter ego, from being accepted as an American no matter how ardently he wishes for acceptance. I argue that though he criticizes a reified American society such as rationalization, quantification, and objectification, his criticism of the society is based on an anachronistic organic romanticism.