Korean American Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perempuan Korea Dalam Film Serial Drama Korea “Jewel in the Palace”

Perempuan Korea dalam Film Serial Drama Korea “Jewel in The Palace” SKRIPSI Diajukan sebagai Salah Satu Syarat untuk Mendapatkan Gelar Sarjana Ilmu Sosial dalam Bidang Antropologi Oleh : Indri Khairani 130905027 DEPARTEMEN ANTROPOLOGI SOSIAL FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 1 Universitas Sumatera Utara UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK PERNYATAAN ORIGINALITAS Perempuan Korea dalam Film Serial Drama Korea“Jewel in The Palace” SKRIPSI Dengan ini saya menyatakan bahwa dalam skripsi ini tidak terdapat karya yang pernah diajukan untuk memperoleh gelar kesarjanaan di suatu perguruan tinggi, dan sepanjang pengetahuan saya tidak terdapat karya atau pendapat yang pernah ditulis atau diterbitkan oleh orang lain, kecuali yang secara tertulis diacu dalam naskah ini dan disebut dalam daftar pustaka. Apabila dikemudian hari ditemukan adanya kecurangan atau tidak seperti yang saya nyatakan di sini, saya bersedia menerima sanksi sesuai dengan peraturan yang berlaku. Medan, Januari 2018 Penulis Indri Khairani i Universitas Sumatera Utara ABSTRAK Indri Khairani, 2018. Judul skripsi: Perempuan Korea dalam Film Serial Drama Korea “Jewel in The Palace”. Skripsi ini terdiri dari 5 BAB, 113 halaman, 18 daftar gambar, 57 daftar pustaka Tulisan ini berjudul Perempuan Korea dalam Film Serial Drama ―Jewel in The Palace”, yang bertujuan untuk mengetahui bagaimana perjuangan sosok seorang perempuan Korea yang tinggal di dalam istana “Gungnyeo” pada masa Dinasti Joseon di anad 15 dalam sebuah drama seri Jewel in The Palace Penelitian ini bersifat kualitatif. Metode yang digunakan adalah analisis wacana, dan model analisis yang digunakan adalalah analisis wacana dari Sara Mills yang merupakan model analisis wacana yang menaruh titik perhatian utama pada wacana mengenai feminisme. -

SHERLOCK in PYONGYANG a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty Of

SHERLOCK IN PYONGYANG A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Asian Studies By Charlotte F. Fitzek, B.A. Washington, DC April 20, 2017 Copyright 2017 by Charlotte F. Fitzek All Rights Reserved ii SHERLOCK IN PYONGYANG Charlotte F. Fitzek, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Victor D. Cha, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Since 2000, the British Council, under the auspices of the Foreign & Commonwealth Office has run an English Language Teacher Training Programme in Pyongyang, North Korea. Its primary aim is to train North Korean teachers on best practices for instructing the English language. The program’s longevity and absence of drama underlines several important characteristics necessary for successful NGO work in North Korea. It highlights that the long-term vision of the DPRK and providing NGO must be shared, and that sustained engagement can lead to continued programming. Embassy support also plays a crucial role in protecting the capabilities of NGOs to perform their functions. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A particular thanks to the interviewees for their time, and to Dr. Cha for his guidance and mentorship. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................3 THE PROGRAMME IN ACTION......................................................................................7 -

French Names Noeline Bridge

names collated:Chinese personal names and 100 surnames.qxd 29/09/2006 13:00 Page 8 The hundred surnames Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Zang Tsang Zang Lin Zhu Chu Gee Zhu Yuanzhang, Zhu Xi Zeng Tseng Tsang, Zeng Cai, Zeng Gong Zhu Chu Zhu Danian Dong, Zhu Chu Zhu Zhishan, Zhu Weihao Jeng Zhu Chu Zhu jin, Zhu Sheng Zha Cha Zha Yihuang, Zhuang Chuang Zhuang Zhou, Zhuang Zi Zha Shenxing Zhuansun Chuansun Zhuansun Shi Zhai Chai Zhai Jin, Zhai Shan Zhuge Chuko Zhuge Liang, Zhan Chan Zhan Ruoshui Zhuge Kongming Zhan Chan Chaim Zhan Xiyuan Zhuo Cho Zhuo Mao Zhang Chang Zhang Yuxi Zi Tzu Zi Rudao Zhang Chang Cheung, Zhang Heng, Ziche Tzuch’e Ziche Zhongxing Chiang Zhang Chunqiao Zong Tsung Tsung, Zong Xihua, Zhang Chang Zhang Shengyi, Dung Zong Yuanding Zhang Xuecheng Zongzheng Tsungcheng Zongzheng Zhensun Zhangsun Changsun Zhangsun Wuji Zou Tsou Zou Yang, Zou Liang, Zhao Chao Chew, Zhao Kuangyin, Zou Yan Chieu, Zhao Mingcheng Zu Tsu Zu Chongzhi Chiu Zuo Tso Zuo Si Zhen Chen Zhen Hui, Zhen Yong Zuoqiu Tsoch’iu Zuoqiu Ming Zheng Cheng Cheng, Zheng Qiao, Zheng He, Chung Zheng Banqiao The hundred surnames is one of the most popular reference Zhi Chih Zhi Dake, Zhi Shucai sources for the Han surnames. It was originally compiled by an Zhong Chung Zhong Heqing unknown author in the 10th century and later recompiled many Zhong Chung Zhong Shensi times. The current widely used version includes 503 surnames. Zhong Chung Zhong Sicheng, Zhong Xing The Pinyin index of the 503 Chinese surnames provides an access Zhongli Chungli Zhongli Zi to this great work for Western people. -

AML 2410—Issues in American Literature and Culture: American Empire and Territories, Spring 2019

AML 2410—Issues in American Literature and Culture: American Empire and Territories, Spring 2019 Instructor: Ms. Rachel Hartnett Section: 5700 Meeting Times: MWF Period 7 Location: Matherly 0114 Email: [email protected] Office: Turlington 4321 Office Hours: Wednesday 9 AM - Noon, or by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION AND OBJECTIVES This course will focus on an important theme in the study of American literature and culture: empire. Many critics and citizens have argued that the United States of America is an inherently anti-imperial nation; however, this ignores the multitude of colonial enterprises and imperialistic tendencies of the U.S. While the founding fathers were resisting British colonial tyranny, American colonists were actively attempting to replace the indigenous population and settle tribal lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. The U.S. continued this removal of the native population, and began its wars of imperialism, in their drive for Manifest Destiny. The involvement of U.S. military forces in the coup of the Hawaiian monarchy, led by the American businessmen in Hawaii, marked the first external connection to imperialism for the United States. Despite the nation’s decision to back independence-minded colonies of Spain in the Spanish-American War, it subsequently took over colonial authority for the Philippines, ignoring the budding First Philippine Republic. The U.S.’s imperialism shifted after World War II and began to be shaped through the use of foreign military bases, particularly in places like Japan and Germany. This only intensified during the Cold War, as the U.S. and the Soviet Union arose as true global powers. -

Yearning for Freedom in Sook Nyul Choi's Year of Impossible Goodbyes

157 영어영문학연구 제44권 제3호 Studies in English Language & Literature (2018) 가을 157-176 http://dx.doi.org/10.21559/aellk.2018.44.3.008 Yearning for Freedom in Sook Nyul Choi’s Year of Impossible Goodbyes Seong Suk Yim (Chonbuk National University) Yim, Seong Suk. “Yearning for Freedom in Sook Nyul Choi’s Year of Impossible Goodbyes.” Studies in English Language & Literature 44.3 (2018): 157-176. Owing to the legacy of Japanese Imperialism, Korea had a shameful past. When two nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced Japan to surrender unconditionally during the War in the Pacific in 1945, people in the United States suddenly felt compassion and sympathy for the Japanese due to the explosions and loss of life. Crucially though, internationally, few people are aware of Japanese colonialism and the atrocious acts committed against Koreans. Year of Impossible Goodbyes is a novel about the plight of Koreans during the period of Japanese colonial rule, and the Koreans peoples' yearning for freedom. This paper studies five symbolic icons representing the freedom, identity and pride of Korean traditional culture and history, and examines how the Korean traditional patriarchal system or family system disintegrated because of Japanese colonial imperialism. This paper outlines how the colonial period school curriculum yielded educational products promoting a transition to the communist ideologies of 'Mother Russia' without clearing away the vestiges of Japanese colonialism, and traces the journey of the heroine who comes to the South seeking for freedom from the Russian communists and the Town Reds in the North. (Chonbuk National University) Key Words: Korean identity, Japanese colonialism, atrocious acts, Russian communism, freedom I. -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Rhetorical Readings of Asian American Literacy Narratives

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ARTICULATING IDENTITIES: RHETORICAL READINGS OF ASIAN AMERICAN LITERACY NARRATIVES Linnea Marie Hasegawa, Doctor of Philosophy, 2004 Dissertation directed by: Professor Kandice Chuh Department of English This dissertation examines how Asian American writers, through what I call critical acts of literacy, discursively (re)construct the self and make claims for alternative spaces in which to articulate their identities as legitimate national subjects. I argue that using literacy as an analytic for studying certain Asian American texts directs attention to the rhetorical features of those texts thereby illuminating how authors challenge hegemonic ideologies about literacy and national identity. Analyzing the audiences and situations of these texts enriches our understanding of Asian American identity formation and the social, cultural, and political functions that these literacy narratives serve for both the authors and readers of the texts. The introduction lays the groundwork for my dissertation’s arguments and method of analysis through a reading of Theresa Cha’s Dictée. By situating readers in such a way that they are compelled to consider their own engagements with literacy and how discourses of literacy and citizenship function to reproduce dominant ideologies, Dictée advances a theoretical model for reading literacy narratives. In subsequent chapters I show how this methodology encourages a kind of reading practice that may serve to transform readers’ ideologies. Part I argues that reading the fictional autobiographies of Younghill Kang and Carlos Bulosan as literacy narratives illuminates the ways in which they simultaneously critique the contradiction between the myth of American democratic inclusion and the reality of exclusion while claiming Americanness through a demonstration of their own and their fictional alter egos’ literacies. -

Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique Truong's the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Spring 5-5-2012 Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique Truong's the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction Debora Stefani Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Stefani, Debora, "Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique ruong'T s the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESISTING DIASPORA AND TRANSNATIONAL DEFINITIONS IN MONIQUE TRUONG’S THE BOOK OF SALT, PETER BACHO’S CEBU, AND OTHER FICTION by DEBORA STEFANI Under the Direction of Ian Almond and Pearl McHaney ABSTRACT Even if their presence is only temporary, diasporic individuals are bound to disrupt the existing order of the pre-structured communities they enter. Plenty of scholars have written on how identity is constructed; I investigate the power relations that form when components such as ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, class, and language intersect in diasporic and transnational movements. How does sexuality operate on ethnicity so as to cause an existential crisis? How does religion function both to reinforce and to hide one’s ethnic identity? Diasporic subjects participate in the resignification of their identity not only because they encounter (semi)-alien, socio-economic and cultural environments but also because components of their identity mentioned above realign along different trajectories, and this realignment undoubtedly affects the way they interact in the new environment. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Diasporic Ethnopoetics Through “Han-Gook”: An Inquiry into Korean American Technicians of the Enigmatic A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by David Hur Committee in charge: Professor Yunte Huang, co-Chair Professor Stephanie Batiste, co-Chair Professor erin Khuê Ninh Professor Sowon Park September 2020 The dissertation of David Hur is approved. ____________________________________________ erin Khuê Ninh ____________________________________________ Sowon Park ____________________________________________ Stephanie Batiste, Committee Co-Chair ____________________________________________ Yunte Huang, Committee Co-Chair September 2020 Diasporic Ethnopoetics Through “Han-Gook”: An Inquiry into Korean American Technicians of the Enigmatic Copyright © 2020 by David Hur iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey has been made possible with support from faculty and staff of both the Comparative Literature program and the Department of Asian American Studies. Special thanks to Catherine Nesci for providing safe passage. I would not have had the opportunities for utter trial and error without the unwavering support of my committee. Thanks to Yunte Huang, for sharing poetry in forms of life. Thanks to Stephanie Batiste, for sharing life in forms of poetry. Thanks to erin Khuê Ninh, for sharing countless virtuous lessons. And many thanks to Sowon Park, for sharing in the witnessing. Thirdly, much has been managed with a little -

Necessary Absence: Familial Distance and the Adult Immigrant Child in Korean American Fiction

NECESSARY ABSENCE: FAMILIAL DISTANCE AND THE ADULT IMMIGRANT CHILD IN KOREAN AMERICAN FICTION by Alexandria Faulkenbury March, 2016 Director of Thesis: Dr. Su-ching Huang Major Department: English In the novels Native Speaker by Chang-rae Lee, The Interpreter by Suki Kim, and Free Food for Millionaires by Min Jin Lee, adult immigrant children feature as protagonists and experience moments of life-defining difficulty and distance associated with their parental relationships. Having come to the U.S. as young children, the protagonists are members of the 1.5 generation and retain some memories of their home country while lacking the deep-seated connections of their parents. They also find themselves caught between first generation immigrants who feel strongly connected to their home country and their second generation peers who feel more connected to the U.S. The absences caused by this in-between status become catalysts for characters addressing the disconnect between their adult selves and their aging or deceased parents. The reconciliation of these disconnections often leads to further examination of competing cultures in these characters’ lives as they struggle to form distinct identities. These divides highlight the chasm between the American dream and the daily realities faced by immigrants in the U.S. and point to larger themes of loss, identity, and family that can be more broadly applied. NECESSARY ABSENCE: FAMILIAL DISTANCE AND THE ADULT IMMIGRANT CHILD IN KOREAN AMERICAN FICTION A Thesis Presented To the Faculty of the Department -

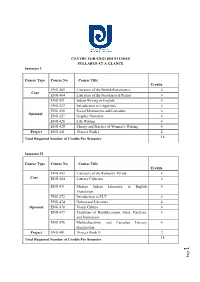

CENTRE for ENGLISH STUDIES SYLLABUS at a GLANCE Semester I

CENTRE FOR ENGLISH STUDIES SYLLABUS AT A GLANCE Semester I Course Type Course No. Course Title Credits ENG 403 Literature of the British Renaissance 4 Core ENG 404 Literature of the Neoclassical Period 4 ENG 421 Indian Writing in English 4 ENG 422 Introduction to Linguistics 4 ENG 426 Social Movements and Literature 4 Optional ENG 427 Graphic Narrative 4 ENG 428 Life Writing 4 ENG 429 Theory and Practice of Women’s Writing 4 Project ENG 441 Project Work I 2 Total Required Number of Credits Per Semester 18 Semester II Course Type Course No. Course Title Credits ENG 453 Literature of the Romantic Period 4 Core ENG 454 Literary Criticism 4 ENG 471 Modern Indian Literature in English 4 Translation ENG 472 Introduction to ELT 4 ENG 474 Nation and Literature 4 Optional ENG 476 Visual Culture 4 ENG 477 Traditions of Republicanism: Ideas, Practices, 4 and Institutions ENG 478 Multiculturalism and Canadian Literary 4 Imagination Project ENG 491 Project Work II 2 Total Required Number of Credits Per Semester 18 1 Page Semester III Course Type Course No. Course Title Credits ENG 503 Literature of the Victorian Period 4 Core ENG 504 Key Directions in Literary Theory 4 ENG 526 Comparative Literary Studies 4 ENG 527 Discourse Analysis 4 ENG 528 Literatures of the Margins 4 Optional ENG 529 Film Studies 4 ENG 530 Literary Historiography 4 ENG 531 Race in the American Literary Imagination 4 ENG 532 Asian Literatures 4 Project ENG 541 Project Work III 2 Total Required Number of Credits Per Semester 18 Semester IV Course Type Course No.