The Ghost As Ghost: Compulsory Rationalism and Asian American Literature, Post-1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acceder a INSOMNIA Nº

7 AÑO 16 - Nº 187 - JULIO 2013 Hard Listening Las memorias de los Rock Bottom Remainders CHARLES ARDAI - JOYLAND - FULL DARK, NO STARS - THE REAPER'S IMAGE - DELVER GLASS - CELSO LUNGHI Nº 187 - JULIO 2013 PORTADA En el año 1992, Kathi Kamen HARD Goldmark, quien trabajaba en el LISTENING EDITORIAL mercado publicitario de los libros, decidió juntar a varios escritores y Las memorias de NOTICIAS formar The Rock Bottom los Rock Bottom IMPRESIONES Remainders, un grupo de música. Remainders ENTREVISTA PÁG. 3 Cuando el pasado mes de mayo Stephen King anunció que EDICIONES Joyland, su última novela NO-FICCIÓN publicada, iba a ser lanzada en formato físico solamente, dejando PINIÓN • Todo lo que hay que saber sobre O de lado el cada vez más popular Under the Dome ORTOMETRAJES ebook para una futura posible C • Las lecturas para el verano, según publicación, debo reconocer que Stephen King FICCIÓN me alegré. A pesar de mi • El cómic Road Rage se publicará intención de aceptar los formatos OTROS MUNDOS en castellano digitales (de hecho, defiendo • Los momentos más destacados del CONTRATAPA muchas de sus ventajas), videochat de Stephen King en la entiendo que la coexistencia que cadena CBS lleva con el libro tradicional es • Joyland en España algo pasajero. En la actualidad, las generaciones de lectores aún ... y otras noticias nacieron y se criaron con el papel PÁG. 4 en la mano. Entienden que el libro es ese y el ebook es una alternativa. PÁG . 25 Joyland en castellano ¿Por qué aferrarse Stephen King Christian DuChateau, de CNN, recomendó recientemente varios al pasado? en "Fresh Air" libros, entre ellos Joyland, de Steve creció comprando novelas de Durante 20 años, Stephen King ha Stephen King. -

To Film Sound Maps: the Evolution of Live Tone’S Creative Alliance with Bong Joon-Ho

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham From ‘Screenwriting for Sound’ to Film Sound Maps: The Evolution of Live Tone’s Creative Alliance with Bong Joon-ho Nikki J. Y. Lee and Julian Stringer Abstract: In his article ‘Screenwriting for Sound’, Randy Thom makes a persuasive case that sound designers should be involved in film production ‘as early as the screenplay…early participation of sound can make a big difference’. Drawing on a critically neglected yet internationally significant example of a creative alliance between a director and post- production team, this article demonstrates that early participation happens in innovative ways in today’s globally competitive South Korean film industry. This key argument is presented through close analysis of the ongoing collaboration between Live Tone - the leading audio postproduction studio in South Korea – and internationally acclaimed director Bong Joon-ho, who has worked with the company on all six of his feature films to date. Their creative alliance has recently ventured into new and ambitious territory as audio studio and director have risen to the challenge of designing the sound for the two biggest films in Korean movie history, Snowpiercer and Okja. Both of these large-scale multi-language movies were planned at the screenplay stage via coordinated use of Live Tone’s singular development of ‘film sound maps’. It is this close and efficient interaction between audio company and client that has helped Bong and Live Tone bring to maturity their plans for the two films’ highly challenging soundscapes. -

Friday 14 February 2020, London. BFI Southbank's TILDA SWINTON

Friday 14 February 2020, London. BFI Southbank’s TILDA SWINTON season, programmed in partnership with the performer and filmmaker herself, will run from 1 – 18 March 2020, celebrating the extraordinary, convention-defying career of one of cinema’s finest and most deft chameleons. The BFI today announce that a number of Swinton’s closest collaborators will join her on stage during the season to speak about their work together including Wes Anderson (Isle of Dogs, The French Dispatch, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Moonrise Kingdom), Bong Joon-ho (Snowpiercer, Okja), Sally Potter (Orlando) and Joanna Hogg (The Souvenir, Caprice). Also announced today is Tilda Swinton’s Film Equipment (28 February – 26 April) a free exhibit to accompany the season which has been curated in close collaboration with BFI and Swinton’s personal archive. Alongside a programme of feature film screenings, shorts and personal favourites, the season will include Tilda Swinton in Conversation with host Mark Kermode on 3 March, during which Swinton will look back on her wide- reaching career as a performer across independent and Hollywood cinema, as well as producer, director and general ally of maverick free spirits everywhere. On the same evening will be Tilda Swinton and Wes Anderson on stage: A Magical Tour of Cinema – a unique chance to hear from two of the most fervent disciples of the church of make believe, as Swinton and Anderson take to the BFI stage to discuss their many collaborations and their film passions. The event will offer a glimpse into their intimate partnership as the two long-time co-conspirators and voracious cinephiles select and explore personal favourite gems from throughout cinema’s history. -

COMPARATIVE LITERATURE (Div

COMPARATIVE LITERATURE (Div. I) Chair, Associate Professor CHRISTOPHER NUGENT Professors: BELL-VILLADA, CASSIDAY, DRUXES, S. FOX, FRENCH, KAGAYA**, NEWMAN***, ROUHI, VAN DE STADT. Associate Professors: C. BOLTON***, DEKEL, S. FOX, HOLZAPFEL, MARTIN, NUGENT, PIEPRZAK***, THORNE, WANG**. Assistant Professors: BRAGGS*, VARGAS. Visiting Assistant Professor: EQEIQ. Students motivated by a desire to study literary art in the broadest sense of the term will find an intellectual home in the Program in Comparative Literature. The Program in Comparative Literature gives students the opportunity to develop their critical faculties through the analysis of literature across cultures, and through the exploration of literary and critical theory. By crossing national, linguistic, historical, and disciplinary boundaries, students of Comparative Literature learn to read texts for the ways they make meaning, the assumptions that underlie that meaning, and the aesthetic elements evinced in the making. Students of Comparative Literature are encouraged to examine the widest possible range of literary communication, including the metamorphosis of media, genres, forms, and themes. Whereas specific literature programs allow the student to trace the development of one literature in a particular culture over a period of time, Comparative Literature juxtaposes the writings of different cultures and epochs in a variety of ways. Because interpretive methods from other disciplines play a crucial role in investigating literature’s larger context, the Program offers courses intended for students in all divisions of the college and of all interests. These include courses that introduce students to the comparative study of world literature and courses designed to enhance any foreign language major in the Williams curriculum. In addition, the Program offers courses in literary theory that illuminate the study of texts of all sorts. -

AML 2410—Issues in American Literature and Culture: American Empire and Territories, Spring 2019

AML 2410—Issues in American Literature and Culture: American Empire and Territories, Spring 2019 Instructor: Ms. Rachel Hartnett Section: 5700 Meeting Times: MWF Period 7 Location: Matherly 0114 Email: [email protected] Office: Turlington 4321 Office Hours: Wednesday 9 AM - Noon, or by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION AND OBJECTIVES This course will focus on an important theme in the study of American literature and culture: empire. Many critics and citizens have argued that the United States of America is an inherently anti-imperial nation; however, this ignores the multitude of colonial enterprises and imperialistic tendencies of the U.S. While the founding fathers were resisting British colonial tyranny, American colonists were actively attempting to replace the indigenous population and settle tribal lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. The U.S. continued this removal of the native population, and began its wars of imperialism, in their drive for Manifest Destiny. The involvement of U.S. military forces in the coup of the Hawaiian monarchy, led by the American businessmen in Hawaii, marked the first external connection to imperialism for the United States. Despite the nation’s decision to back independence-minded colonies of Spain in the Spanish-American War, it subsequently took over colonial authority for the Philippines, ignoring the budding First Philippine Republic. The U.S.’s imperialism shifted after World War II and began to be shaped through the use of foreign military bases, particularly in places like Japan and Germany. This only intensified during the Cold War, as the U.S. and the Soviet Union arose as true global powers. -

Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique Truong's the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Spring 5-5-2012 Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique Truong's the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction Debora Stefani Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Stefani, Debora, "Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique ruong'T s the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESISTING DIASPORA AND TRANSNATIONAL DEFINITIONS IN MONIQUE TRUONG’S THE BOOK OF SALT, PETER BACHO’S CEBU, AND OTHER FICTION by DEBORA STEFANI Under the Direction of Ian Almond and Pearl McHaney ABSTRACT Even if their presence is only temporary, diasporic individuals are bound to disrupt the existing order of the pre-structured communities they enter. Plenty of scholars have written on how identity is constructed; I investigate the power relations that form when components such as ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, class, and language intersect in diasporic and transnational movements. How does sexuality operate on ethnicity so as to cause an existential crisis? How does religion function both to reinforce and to hide one’s ethnic identity? Diasporic subjects participate in the resignification of their identity not only because they encounter (semi)-alien, socio-economic and cultural environments but also because components of their identity mentioned above realign along different trajectories, and this realignment undoubtedly affects the way they interact in the new environment. -

Writers' Craft Box Fiction

Writers Craft Box Page 1 of 19 The Write Place At the Write Time Home Come in...and be captivated... About Us Search Announcements Interviews Writers' Craft Box Fiction Poetry What this section is intended to do: Give writers suggested hints, "Our Stories" non-fiction resources, and advice. Writers' Craft Box How to use: Pick and choose what you feel is most helpful and derive Book Reviews inspiration from it- most importantly, Writers' Challenge! HAVE FUN! What a Writers' Craft Box is: Say Submission Guidelines you're doing an art project and you want Feedback & Questions to spice it up a bit. You reach into a "Arts and Crafts" N.M.B Copyright 2008 seemingly bottomless box full of Artists' Gallery colorful art/craft supplies and choose only the things that speak to Literary Arts Patrons you. You take only what you need to feel Indie Bookstores that you've fully expressed yourself. Then, you go about doing your individual Scrapbook of Five Years project adding just the right amount of Archives everything you've chosen until you reach a product that suits you completely. So, Inscribing Industry Blog this is on that concept. Reach in, find the things that inspire you, use the tools http://www.thewriteplaceatthewritetime.org/writerscraftbox.html 10/ 11/ 2013 Writers Craft Box Page 2 of 19 that get your writing going and see it as fulfilling your self-expression as opposed to following rules. Writing is art and art is supposed to be fun, relaxing, healing and nurturing. It's all work and it's all play at the same time. -

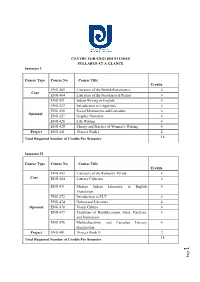

CENTRE for ENGLISH STUDIES SYLLABUS at a GLANCE Semester I

CENTRE FOR ENGLISH STUDIES SYLLABUS AT A GLANCE Semester I Course Type Course No. Course Title Credits ENG 403 Literature of the British Renaissance 4 Core ENG 404 Literature of the Neoclassical Period 4 ENG 421 Indian Writing in English 4 ENG 422 Introduction to Linguistics 4 ENG 426 Social Movements and Literature 4 Optional ENG 427 Graphic Narrative 4 ENG 428 Life Writing 4 ENG 429 Theory and Practice of Women’s Writing 4 Project ENG 441 Project Work I 2 Total Required Number of Credits Per Semester 18 Semester II Course Type Course No. Course Title Credits ENG 453 Literature of the Romantic Period 4 Core ENG 454 Literary Criticism 4 ENG 471 Modern Indian Literature in English 4 Translation ENG 472 Introduction to ELT 4 ENG 474 Nation and Literature 4 Optional ENG 476 Visual Culture 4 ENG 477 Traditions of Republicanism: Ideas, Practices, 4 and Institutions ENG 478 Multiculturalism and Canadian Literary 4 Imagination Project ENG 491 Project Work II 2 Total Required Number of Credits Per Semester 18 1 Page Semester III Course Type Course No. Course Title Credits ENG 503 Literature of the Victorian Period 4 Core ENG 504 Key Directions in Literary Theory 4 ENG 526 Comparative Literary Studies 4 ENG 527 Discourse Analysis 4 ENG 528 Literatures of the Margins 4 Optional ENG 529 Film Studies 4 ENG 530 Literary Historiography 4 ENG 531 Race in the American Literary Imagination 4 ENG 532 Asian Literatures 4 Project ENG 541 Project Work III 2 Total Required Number of Credits Per Semester 18 Semester IV Course Type Course No. -

Japanese American Citizens League (75C Postpald Us.) 25 Cents

THE PACIFIC CITIZEN Established 1929 National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens League (75c Postpald us.) 25 Cents #2,581 Vol. 110 No.25 ISSN: 0030-8579 941 East 3rd St., Suite 200, Los Angeles, CA 90013 Friday. June 29. 1990 • New Notional JACL Officers Toke Office RESOLUTION PRAISES WWWS NISEI DRAFT RESISTERS SAN DIEGO, Calif. - Candidates for the ix ational Board Offices were JACL A H I C W d elected last week at the 31st Biennial JACL Convention. All ran without oppo - cts to eo ommun.ety oun 5 ilion but required a imple majority. The new JACL national officer.;, with the number of vote received, are: ~ident-Cressey akagawa (inl:), 88; vice pre ident for generaf operauons-PrisciUa Ouchida {mc.),73; Lillian Kimur'd (write·in), I; vice pl"C.'ldent for public affairs Floyd Mon, 72, vice pre ident for planning and development-William Kaneko. 9: Vice president for membership and >ervicl!lr- Ted 1asurnoto, I; secretary·treasurer-Tom akao Jr , 50; Randolph hibata (write-in). 1 AI 0 elected were the two board member.; repre enting youth. Kim Tachikl defeated Joe Takano for the po t of youth repre entalive, and Tri ha Murakawa, runmng unoppo ed. was elected national youth council chatr Only the youth repre entatlve cast ballots for the e offices 31 st Biennial JACL Convention in San Diego Ends; LEC Honors 12 • By Harry K. Honda from EnomOto; en Spark M. Matsunaga, POSl - humou Iy from Shig Wakamatsu; Sen i}aniel SAN DIEGO - Curtains for the 31 t Photo by Koren Serigucho K Akaka (D-Hawaii) In absenua from Mae Biennial ational JACL Convention Takahashi; Rep. -

Klassekritikkens Utvikling I Bong Joon-Ho Sin Filmografi

Haram, Sindre Mangen Klassekritikkens utvikling i Bong Joon-Ho sin filmografi Bacheloroppgave i Filmvitenskap Veileder: Gjelsvik, Anne Mai 2020 Bacheloroppgave NTNU Det humanistiske fakultet Det humanistiske Institutt for kunst- og medievitenskap Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet Norges Haram, Sindre Mangen Klassekritikkens utvikling i Bong Joon- Ho sin filmografi Bacheloroppgave i Filmvitenskap Veileder: Gjelsvik, Anne Mai 2020 Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet Det humanistiske fakultet Institutt for kunst- og medievitenskap Bacheloroppgave Sindre Mangen Haram FILM2000 Innholdsfortegnelse Innholdsfortegnelse......................................................................................Side 1 Innledning.....................................................................................................Side 2 Hvem er Bong Joon-Ho?..............................................................................Side 3 Samfunnet i Sør-Korea.................................................................................Side 3 Hva menes med «klasse»?............................................................................Side 4 Barking Dogs Never Bite.............................................................................Side 5 Memories of Murder.....................................................................................Side 7 The Host.......................................................................................................Side 8 Mother..........................................................................................................Side -

Tim Yamamura Dissertation Final

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Science Fiction Futures and the Ocean as History: Literature, Diaspora, and the Pacific War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3j87r1ck Author Yamamura, Tim Publication Date 2014 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ SCIENCE FICTION FUTURES AND THE OCEAN AS HISTORY: LITERATURE, DIASPORA, AND THE PACIFIC WAR A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LITERATURE by Timothy Jitsuo Yamamura December 2014 The Dissertation of Tim Yamamura is approved: __________________________________________ Professor Rob Wilson, chair __________________________________________ Professor Karen Tei Yamashita __________________________________________ Professor Christine Hong __________________________________________ Professor Noriko Aso __________________________________________ Professor Alan Christy ________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © 2014 Tim Yamamura All rights reserved Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Introduction: Science Fiction and the Perils of Prophecy: Literature, 1 Diasporic “Aliens,” and the “Origins” of the Pacific War Chapter 1: Far Out Worlds: American Orientalism, Alienation, and the 49 Speculative Dialogues of Percival Lowell and Lafcadio Hearn Chapter -

Awards Appendix

Appendix A: Awards Jane Addams Book Award The Jane Addams Children’s Book Award has been presented annually since 1953 by the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the Jane Addams Peace Association to the children’s book of the preceding year that most effectively promotes the cause of peace, social justice and world community 1953 People Are Important by Eva Knox Evans (Capital) 1954 Stick-in-the-Mud by Jean Ketchum (Cadmus Books, E.M. Hale) 1955 Rainbow Round the World by Elizabeth Yates (Bobbs-Merrill) 1956 Story of the Negro by Arna Bontemps (Knopf) 1957 Blue Mystery by Margot Benary-Isbert (Harcourt Brace) 1958 The Perilous Road by William O. Steele (Harcourt Brace) 1959 No Award Given 1960 Champions of Peace by Edith Patterson Meyer (Little, Brown) 1961 What Then, Raman? By Shirley L. Arora (Follett) 1962 The Road to Agra by Aimee Sommerfelt (Criterion) 1963 The Monkey and the Wild, Wild Wind by Ryerson Johnson (Abelard-Schuman) 1964 Profiles in Courage: Young Readers Memorial Edition by John F. Kennedy (Harper & Row) 1965 Meeting with a Stranger by Duane Bradley (Lippincott) 1966 Berries Goodman by Emily Cheney Nevel (Harper & Row) 1967 Queenie Peavy by Robert Burch (Viking) 1968 The Little Fishes by Erick Haugaard (Houghton Mifflin) 1969 The Endless Steppe: Growing Up in Siberia by Esther Hautzig (T.Y. Crowell) 1970 The Cay by Theodore Taylor (Doubleday) 1971 Jane Addams: Pioneer of Social Justice by Cornelia Meigs (Little, Brown) 1972 The Tamarack Tree by Betty Underwood (Houghton Mifflin) 1973 The Riddle of Racism by S.