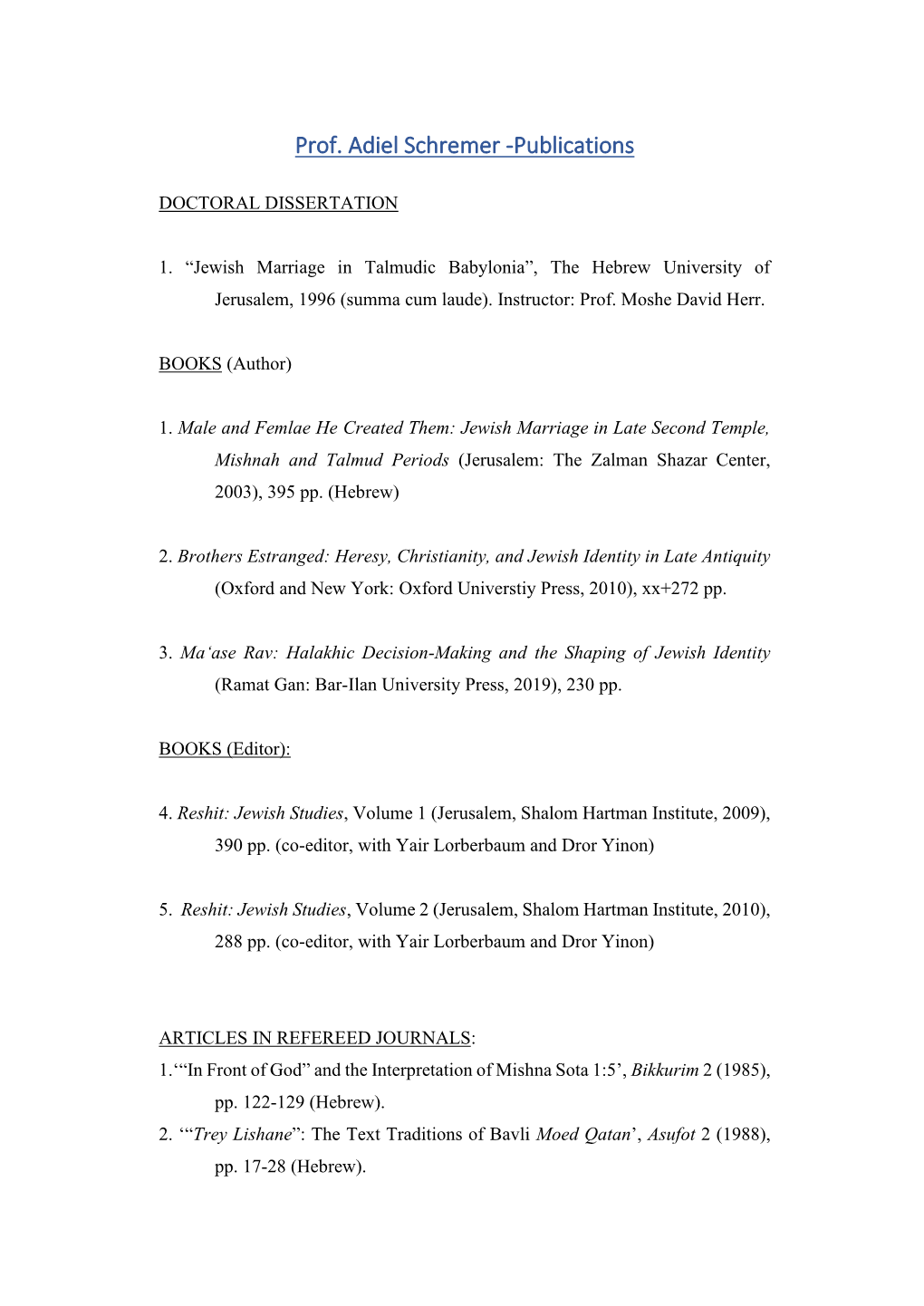

Prof. Adiel Schremer -Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Foundations I Hebrew Literacy I Jewish Foundations II Hebrew

Grade JUDAIC STUDIES HEBREW K Jewish Foundations I Hebrew Literacy I Prayer, Shabbat & Holidays, and the Introduction to Conversational Weekly Torah Portion Hebrew ● Students utilize Hebrew conversation, ● Students begin to speak in music, art, visuals, and manipulatives to conversational Hebrew learn prayers, explore Shabbat and the through immersion; Jewish holidays, and begin to learn ● acquire a working vocabulary about the weekly Torah portion. of everyday Hebrew words; ● These create experiential learning and opportunities that foster deep emotional ● learn the letters of the Hebrew connections between children and their alphabet. Jewish heritage and practices. ● Students draw connections between each subject area and the Land of Israel. 1 Jewish Foundations II Hebrew Literacy II Prayer, Shabbat & Holidays, and the Conversational Hebrew, Reading, Weekly Torah Portion and Writing ● In addition to extending their knowledge ● Students learn to read and of prayer, Shabbat and holidays, and write fluently in Hebrew, and weekly Torah portion, students: ● significantly expand their ● contextualize the holidays against the working Hebrew vocabularies backdrop of the Jewish calendar, and and level of conversational ● become familiar with the wider narrative fluency. arc of the Torah portions. 2 Jewish Foundations III Hebrew Literacy III Prayer, Shabbat & Holidays, and the Advanced Hebrew Literacy; Weekly Torah Portion Fundamentals of Hebrew Grammar ● Students continue to deepen their ● Students achieve increased knowledge of the prayers, holidays, and mastery of reading, writing, weekly Torah portion; and speaking Hebrew; ● learn about key stories from the rabbinic ● further extend their Midrash; and vocabularies; and ● memorize key concepts, including the ● gain their first exposure to the dates of the Jewish holidays and names fundamentals of Hebrew of the Torah portions. -

Mishna Rishona Brochure

משנה ראשונה Mishna Rishona Master Mishnayos. Anywhere. Anytime. What is Mishna Rishona? Learn, review and master Mishnayos at your own pace. Call in, listen and learn one Mishna at a time, starting with Seder Moed. As you learn, you can bookmark, pause, rewind and fast forward. Each Mishna is skillfully brought to life in a clear and fascinating way. Perfect for the boy who wants to review the Mishnayos he learned in Yeshiva or for an advanced boy who wants to complete additional Mesechtas. Seder Moed, Kodshim, Nezikin, and Nashim are available and Seder Zeraim is currently in progress. Measure your progress. Each Perek of Mishna is followed by review questions which can be used to accumulate points. With these points you can measure your progress. Parents may wish to reward their children for points earned. Set up your account today by calling our Member Hotline 929.299.6700 929.265.6700 Anywhere. Our Membership hotline number works from anywhere around the globe. Whether you live in New York or in Australia you can join the Mishna Rishona Program and learn Mishnayos. Going to visit your Zeidy and Bubby in Florida, your Savta in Israel, or your cousins in Wyoming does not have to keep you back from continuing to learn Mishnayos and keeping up with your goals. Anytime. Its up to you! You can call in the morning, you can call in the evening, you can even call while waiting for an appointment. You can call whenever you have a couple of minutes! The hotline is always open, always available! Anyhow. -

Nickelsburg Final.Indd

1 Sects, Parties, and Tendencies Judaism of the last two centuries b.c.e. and the first century c.e. saw the devel- opment of a rich, variegated array of groups, sects, and parties. In this chapter we shall present certain of these groupings, both as they saw themselves and as others saw them. Samaritans, Hasideans, Pharisees and Sadducees, Essenes, and Therapeutae will come to our attention, as will a brief consideration of the hellenization of Judaism and appearance of an apocalyptic form of Judaism. The diversity—which is not in name only, but also in belief and practice, order of life and customary conduct, and the cultural and intellectual forms in which it was expressed—raises several questions: How did this diversity originate? What were the predominating characteristics of Judaism of that age or, indeed, were there such? Was there a Judaism or were there many Judaisms? How do rabbinic Juda- ism and early Christianity emerge from it or them? The question of origins takes us back into the unknown. The religious and social history of Judaism in the latter part of the Persian era and in the Ptolemaic age (the fourth and third centuries b.c.e.) is little documented. The Persian prov- ince of Judah was a temple state ruled by a high-priestly aristocracy. Although some of the later parts of the Bible were written then and others edited at that time, and despite some new information from the Dead Sea manuscripts, the age itself remains largely unknown. Some scholars have tried to reconstruct the history of this period by work- ing back from the conflict between Hellenism and Judaism that broke into open revolt in the early second century.1 With the conquests of Alexander the Great in 334–323 b.c.e.—and indeed, somewhat earlier—the vital and powerful culture of the Greeks and the age-old cultures of the Near East entered upon a process of contact and conflict and generated varied forms of religious synthesis and self- definition. -

Sukkot Potpourri

Sukkot Potpourri [note: This document was created from a selection of uncited study handouts and academic texts that were freely quoted and organized only for discussion purposes.] Byron Kolitz 30 September 2020; 12 Tishrei 5781 Midrash Tehillim 17, Part 5 - Why is Sukkot so soon after Yom Kippur? (Also referred to as Midrash Shocher Tov; its beginning words are from Proverbs 11:27. The work is known since the 11th century; it covers only Psalms 1-118.) In your right hand there are pleasures (Tehillim 16:11). What is meant by the word pleasures? Rabbi Abin taught, it refers to the myrtle, the palm-branch, and the willow which give pleasure. These are held in the right hand, for according to the rabbis, the festive wreath (lulav) should be held in the right hand, and the citron in the left. What kind of victory is meant in the phrase? As it appears in the Aramaic Bible: ‘the sweetness of the victory of your right hand’. That kind of victory is one in which the victor receives a wreath. For according to the custom of the world, when two charioteers race in the hippodrome, which of them receives a wreath? The victor. On Rosh Hashanah all the people of the world come forth like contestants on parade and pass before G-d; the children of Israel among all the people of the world also pass before Him. Then, the guardian angels of the nations of the world declare: ‘We were victorious, and in the judgment will be found righteous.’ But actually no one knows who was victorious, whether the children of Israel or the nations of the world were victorious. -

In Search of the Essence of a Talmudic Debate: the Case of Water Used by a Baker

chapter 4 In Search of the Essence of a Talmudic Debate: the Case of Water Used by a Baker 1 Introduction This chapter discusses a very short sugya about the status of water used by a baker for wetting his hands while making dough for unleavened bread at Passover. What should be done with this water during Passover, when one is forbidden to possess leaven? This very minor Talmudic topic is treated in parallel texts in the Mishnah and Tosefta and is mentioned briefly (2–3 lines) in both Talmudim. This provides us with an opportunity to delve into the ex- plicit and implicit interpretive assumptions of modern scholarly approaches to reading Talmudic literature as well as to demonstrate the advantages of my own approach. The relationship between the corresponding texts in the Mishnah and the Tosefta is debated by two leading scholars, Shamma Friedman and Robert Brody. Their dispute concerning this case study reflects the different approach- es to parallel Tannaitic sources they imbibed in their respective schools, the Hebrew University in Jerusalem (Brody) and the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York (Friedman). In my view, both are overly eager to prove that the differences between parallel texts in the Mishnah and Tosefta do not reflect disagreement between the sources’ authors, but are the result of editorial considerations or of the vicissitudes of oral transmission. I will argue that it is possible to ascribe disagreement to parallel sources without passing judgment either on their chronological order or on whether one of the sources -

Library of Congress Classification

KB RELIGIOUS LAW IN GENERAL. COMPARATIVE RELIGIOUS LAW. KB JURISPRUDENCE Religious law in general. Comparative religious law. Jurisprudence Class here comparative studies on different religious legal systems, as well as intra-denominational comparisons (e.g. different Christian religious legal systems) Further, class here comparative studies on religious legal systems with other legal systems, including ancient law For comparison of a religious legal system with the law of two or more jurisdictions, see the religious system (e.g. Islamic law compared to Egyptian and Malaysian law, see KBP) Comparisons include both systematic-theoretical elaborations as well as parallel presentations of different systems For influences of a religious legal system on the law of a particuar jurisdiction, see the jurisdiction For works on law and religion see BL65.L33 Bibliography For personal bibliography or bibliography relating to a particular religious system or subject, see the appropriate KB subclass 2 Bibliography of bibliography. Bibliographical concordances 4 Indexes for periodical literature, society publications, collections, etc. Periodicals For KB8-KB68, the book number, derived from the main entry, is determined by the letters following the letter for which the class number stands, e.g. KB11.I54, Dine Yisrael 7 General Jewish 8 A - Archiu 8.3 Archiv - Archivz e.g. 8.3.R37 Archives d'histoire du droit oriental 9 Archiw - Az 9.3 B e.g. 9.3.U43 Bulletin/International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists 10 C 11 D e.g. 11.I54 Dine Yisrael: shanaton le-mishpat ʻIvri ule-mishpahah be-Yiʼsrael 12 E - Etuder 12.3 Etudes - Ez 13 F 14 G 15 H 16 I e.g. -

SYNOPSIS the Mishnah and Tosefta Are Two Related Works of Legal

SYNOPSIS The Mishnah and Tosefta are two related works of legal discourse produced by Jewish sages in Late Roman Palestine. In these works, sages also appear as primary shapers of Jewish law. They are portrayed not only as individuals but also as “the SAGES,” a literary construct that is fleshed out in the context of numerous face-to-face legal disputes with individual sages. Although the historical accuracy of this portrait cannot be verified, it reveals the perceptions or wishes of the Mishnah’s and Tosefta’s redactors about the functioning of authority in the circles. An initial analysis of fourteen parallel Mishnah/Tosefta passages reveals that the authority of the Mishnah’s SAGES is unquestioned while the Tosefta’s SAGES are willing at times to engage in rational argumentation. In one passage, the Tosefta’s SAGES are shown to have ruled hastily and incorrectly on certain legal issues. A broader survey reveals that the Mishnah also contains a modest number of disputes in which the apparently sui generis authority of the SAGES is compromised by their participation in rational argumentation or by literary devices that reveal an occasional weakness of judgment. Since the SAGES are occasionally in error, they are not portrayed in entirely ideal terms. The Tosefta’s literary construct of the SAGES differs in one important respect from the Mishnah’s. In twenty-one passages, the Tosefta describes a later sage reviewing early disputes. Ten of these reviews involve the SAGES. In each of these, the later sage subjects the dispute to further analysis that accords the SAGES’ opinion no more a priori weight than the opinion of individual sages. -

Significant Exegetical Aspects of the Sadducees' Question to Jesus Regarding the Resurrection

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Master of Sacred Theology Thesis Concordia Seminary Scholarship 5-1-1984 Significant Exegetical Aspects of the Sadducees' Question to Jesus Regarding the Resurrection Wilfred Karsten Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/stm Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Karsten, Wilfred, "Significant Exegetical Aspects of the Sadducees' Question to Jesus Regarding the Resurrection" (1984). Master of Sacred Theology Thesis. 64. https://scholar.csl.edu/stm/64 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Sacred Theology Thesis by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter I. THE SADDUCEES Josephus and the New Testament as Sources of Information . • • • • • • • 4 History . • • . • . • • • • • . • • 12 Name • . • . 23 Doctrinal Position • • • • . • • • 32 Ultimate Demise . • • . • • • • • • 39 Summary • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • . 40 II. A COMPARISON OF THE SYNOPTIC ACCOUNTS OF THE SADDUCEES' QUESTION TO JESUS Textual Variants • • . • • • • . • • • • • • 42 Context . • • • • • . • . • • • • • • • 47 Levirate Marriage as the Framework for the Question on the Resurrection 57 The Resurrection • . • • • • • 64 Summary . • • • • 71 III. RELATED ISSUES IN HEBREW, GREEK, AND JEWISH THOUGHT Hebrew Anthropology • • . • • • • • • • 73 Greek Dualism • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • 82 Resurrection Versus Immortality. 85 Conclusion • • • • . • • . • • • • • . • 110 IV. THE CITATION FROM EXODUS THREE The Introduction of the Quotation . • • • . 111 The Context of Exodus Three and the Significance of "The God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob" . -

Rereading the Mishnah

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Martin Hengel and Peter Schäfer 109 Judith Hauptman Rereading the Mishnah A New Approach to Ancient Jewish Texts Mohr Siebeck JUDITH HAUPTMAN: born 1943; BA in Economics at Barnard College (Columbia Univer- sity); BHL, MA, PhD in Talmud and Rabbinics at Jewish Theological Seminary; is currently E. Billy Ivry Professor of Talmud and Rabbinic Culture, Jewish Theological Seminary, NY. ISBN 3-16-148713-3 ISSN 0721-8753 (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism) Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; de- tailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2005 by Judith Hauptman / Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Guide-Druck in Tiibingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. •mm i^DH tn In memory of my brother, Philip Jonathan Hauptman, a heroic physician, who died on Rosh Hodesh Nisan 5765 Contents Preface IX Notes to the Reader XII Abbreviations XIII Chapter 1: Rethinking the Relationship between the Mishnah and the Tosefta 1 A. Two Illustrative Sets of Texts 3 B. Theories of the Tosefta's Origins 14 C. New Model 17 D. Challenges and Responses 25 E. This Book 29 Chapter 2: The Tosefta as a Commentary on an Early Mishnah 31 A. -

Yevamos 049.Pub

"כ ט חשו תשעה” Shabbos, November 22, 2014 יבמות מ”ט OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT 1) MISHNAH: The Mishnah begins with a presentation The prophecy of Moshe Rabeinu כל הנביאי נסתכלו באספקלריא שאינה מאירה , משה רבינו -of the different opinions regarding the type of illicit rela נסתכל באספקלריא המאירה tionship that will produce a mamzer. The Mishnah con- cludes with a discussion of the prohibition against marry- ambam (Yesodei HaTorah 7:6) writes: What is the ing one’s wife’s sister and one’s chalutza’s sister. R difference between the prophecy of Moshe and that of all 2) Clarifying the source for the different positions other prophets? Divine insight is bestowed upon all the The source for R’ Akiva’s position is identified. other prophets in a dream or vision. Moshe, our teacher, An alternative source is presented. would prophesy while standing awake, as the verse says The source for Shimon Hateimani’s position is identi- (Bamidbar 7:89), “When Moshe came into the Ohel fied. Moed to speak to Him, he heard the voice speaking to The source for R’ Yehoshua’s position is identified. him.” Abaye asserts that all opinions agree that the child is Divine insight is bestowed upon all the other proph- not a mamzer if one had relations with a nidah or a sotah. ets through the medium of an angel. Therefore they per- The reason for Abaye’s assertion is presented, followed ceive only metaphoric imagery and allegories. Moshe by a Baraisa that echoes his rulings. would prophesy without the medium of an angel, as the The Gemara explains why Abaye did not include the Torah states (ibid. -

Reflections on the Exemption of Women from Time-Bound Commandments

JᴜᴅᴀIᴄᴀ: Nᴇᴜᴇ ᴅIGIᴛᴀᴌᴇ FᴏᴌGᴇ 1 (2020) https://doi.org/10.36950/jndf.1.4 c b – ᴄᴄ BY 4.0 Law, Hierarchy, and Gender: Reflections on the Exemption of Women from Time-Bound Commandments Valérie Rhein Universität Luzern [email protected] Abstract: Why do the tannaim exempt women from time-bound commandments (m. Qid dushin 1:7)? In this paper it is argued that the unequal levels of obligation for men and women in rabbinic Judaism creates a hierarchy of mitzvot between them that mimics and virtually replaces the earlier biblical hierarchy of mitzvot between priests and Israel. In both constellations the rabbis consider the obligation to fulfill more commandments to be a privilege. The similarity between the hierarchies priests–Israel and men–women becomes apparent when the selection of commandments from which the tannaim and the amoraim explicitly exempt women are examined more closely: Many of them – the time-bound commandments shofar, lulav, tzitzit, tefillin, and shema as well as the non-time-bound mitzvah of Torah study – share a common feature, namely, their function as “ersatz Temple rituals.” During the transition from a Temple- oriented, priest-based Judaism to a study-oriented rabbinic Judaism, rituals such as these played a crucial role. Judaism is a religion of time aiming at the sanctification of time.¹ What is the difference between a Jewish man and a Jewish woman? From the perspective of observance and ritual practice, the answer is: In rabbinic Judaism, men are obligated, as a rule, to fulfill all the commandments, while women are not. This distinction between the sexes is based on a rabbinic principle handed down in the Mishnah in tractate Qiddushin: the men are obli—[ לכ תוצמ השע ןמזהש המרג ] All positive time-related obligations gated and the women are exempt, and all positive commandments not time-related both men and women are obligated. -

Ruah Ha-Kodesh in Rabbinic Literature

The Dissertation Committee for Julie Hilton Danan Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE DIVINE VOICE IN SCRIPTURE: RUAH HA-KODESH IN RABBINIC LITERATURE Committee: Harold A. Liebowitz , Supervisor Aaron Bar -Adon Esther L. Raizen Abraham Zilkha Krist en H. Lindbeck The Divine Voice in Scripture: Ruah ha-Kodesh in Rabbinic Literature by Julie Hilton Danan, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2009 Dedication To my husband, Avraham Raphael Danan Acknowledgements Thank you to the University of Texas at Austin Graduate School, the Middle Eastern Studies Department, and particularly to the Hebrew Studies faculty for their abundant support over my years of study in graduate school. I am especially grateful to the readers of my dissertation for many invaluable suggestions and many helpful critiques. My advisor, Professor Harold Liebowitz, has been my guide, my mentor, and my academic role model throughout the graduate school journey. He exemplifies the spirit of patience, thoughtful listening, and a true love of learning. Many thanks go to my readers, professors Esther Raizen, Avraham Zilkha, Aaron Bar-Adon, and Kristen Lindbeck (of Florida Atlantic University), each of whom has been my esteemed teacher and shared his or her special area of expertise with me. Thank you to Graduate Advisor Samer Ali and the staff of Middle Eastern Studies, especially Kimberly Dahl and Beverly Benham, for their encouragement and assistance.