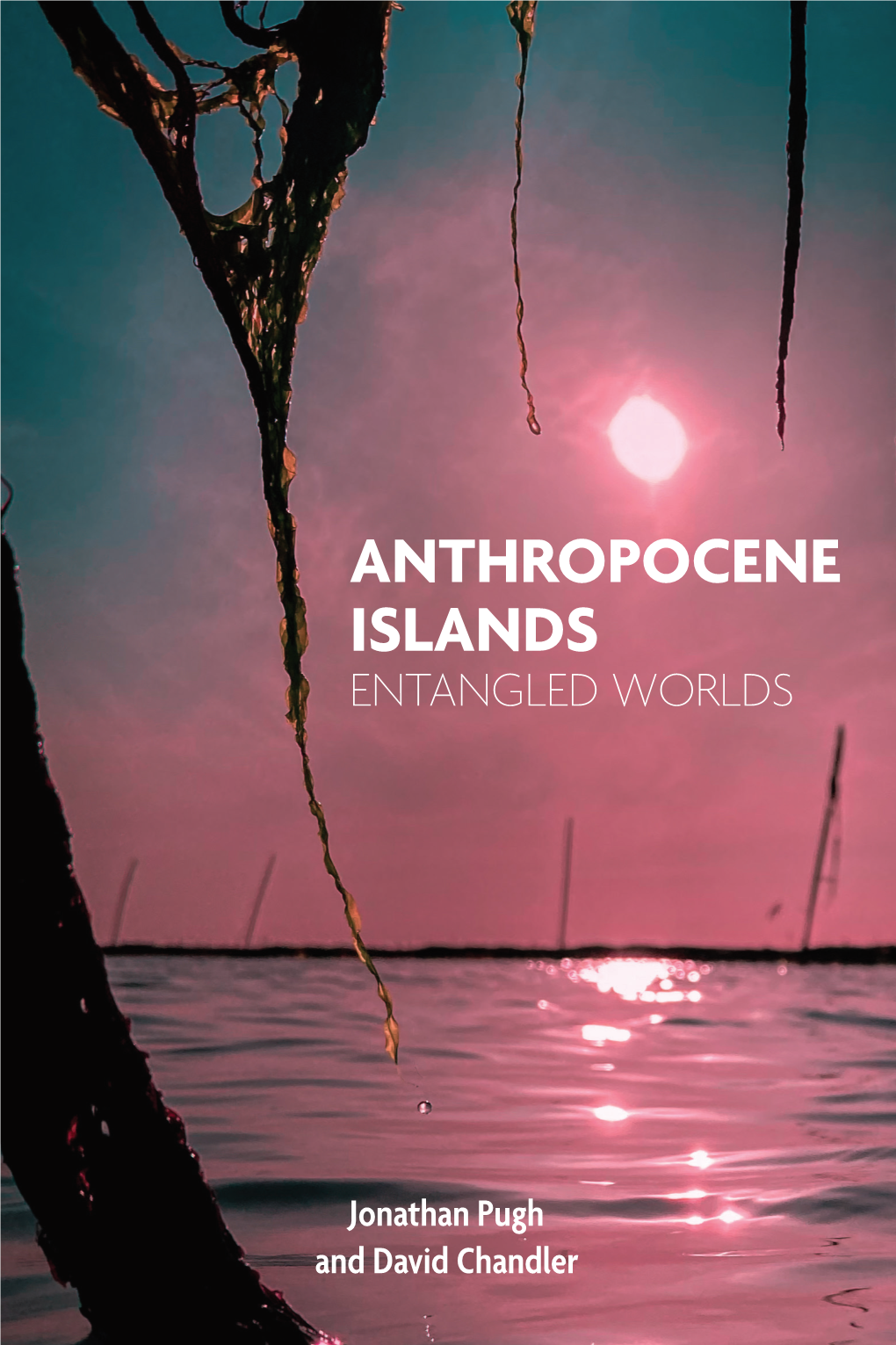

Anthropocene Islands: Entangled Worlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can Preferred Atmospheric Circulation Patterns Over the North-Atlantic-Eurasian Region Be Associated with Arctic Sea Ice Title Loss?

Can preferred atmospheric circulation patterns over the North-Atlantic-Eurasian region be associated with arctic sea ice Title loss? Author(s) Crasemann, Berit; Handorf, Doerthe; Jaiser, Ralf; Dethloff, Klaus; Nakamura, Tetsu; Ukita, Jinro; Yamazaki, Koji Polar Science, 14, 9-20 Citation https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2017.09.002 Issue Date 2017-12 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/68177 © 2017, Elsevier. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license Rights http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Rights(URL) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Type article File Information 1-s2.0-S1873965217300580-main.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Polar Science 14 (2017) 9e20 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Polar Science journal homepage: https://www.evise.com/profile/#/JRNL_POLAR/login Can preferred atmospheric circulation patterns over the North- Atlantic-Eurasian region be associated with arctic sea ice loss? * Berit Crasemann a,Dorthe€ Handorf a, , Ralf Jaiser a, Klaus Dethloff a, Tetsu Nakamura b, Jinro Ukita c, Koji Yamazaki b a Alfred-Wegener-Institut, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, Potsdam, Germany b Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan c Niigata University, Niigata, Japan article info abstract Article history: In the framework of atmospheric circulation regimes, we study whether the recent Arctic sea ice loss and Received 19 May 2017 Arctic Amplification are associated with changes in the frequency of occurrence of preferred atmospheric Received in revised form circulation patterns during the extended winter season from December to March. -

The Leadership Issue

SUMMER 2017 NON PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID ROLAND PARK COUNTRY SCHOOL connections BALTIMORE, MD 5204 Roland Avenue THE MAGAZINE OF ROLAND PARK COUNTRY SCHOOL Baltimore, MD 21210 PERMIT NO. 3621 connections THE ROLAND PARK COUNTRY SCHOOL COUNTRY PARK ROLAND SUMMER 2017 LEADERSHIP ISSUE connections ROLAND AVE. TO WALL ST. PAGE 6 INNOVATION MASTER PAGE 12 WE ARE THE ROSES PAGE 16 ADENA TESTA FRIEDMAN, 1987 FROM THE HEAD OF SCHOOL Dear Roland Park Country School Community, Leadership. A cornerstone of our programming here at Roland Park Country School. Since we feel so passionately about this topic we thought it was fitting to commence our first themed issue of Connections around this important facet of our connections teaching and learning environment. In all divisions and across all ages here at Roland Park Country School — and life beyond From Roland Avenue to Wall Street graduation — leadership is one of the connecting, lasting 06 President and CEO of Nasdaq, Adena Testa Friedman, 1987 themes that spans the past, present, and future lives of our (cover) reflects on her time at RPCS community members. Joe LePain, Innovation Master The range of leadership experiences reflected in this issue of Get to know our new Director of Information and Innovation Connections indicates a key understanding we have about the 12 education we provide at RPCS: we are intentional about how we create leadership opportunities for our students of today — and We Are The Roses for the ever-changing world of tomorrow. We want our students 16 20 years. 163 Roses. One Dance. to have the skills they need to be successful in the future. -

Fossil Fuels

Gonzaga Debate Institute 1 Warming Core Warming Bad Gonzaga Debate Institute 2 Warming Core ***Science Debate*** Gonzaga Debate Institute 3 Warming Core Warming Real – Generic Warming real - consensus Brooks 12 - Staff writer, KQED news (Jon, staff writer, KQED news, citing Craig Miller, environmental scientist, 5/3/12, "Is Climate Change Real? For the Thousandth Time, Yes," KQED News, http://blogs.kqed.org/newsfix/2012/05/03/is- climate-change-real-for-the-thousandth-time-yes/) BROOKS: So what are the organizations that say climate change is real? MILLER: Virtually ever major, credible scientific organization in the world. It’s not just the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Organizations like the National Academy of Sciences, the American Geophysical Union, the American Association for the Advancement of Science. And that's echoed in most countries around the world. All of the most credible, most prestigious scientific organizations accept the fundamental findings of the IPCC. The last comprehensive report from the IPCC, based on research, came out in 2007. And at that time, they said in this report, which is known as AR-4, that there is "very high confidence" that the net effect of human activities since 1750 has been one of warming. Scientists are very careful, unusually careful, about how they put things. But then they say "very likely," or "very high confidence," they’re talking 90%. BROOKS: So it’s not 100%? MILLER: In the realm of science; there’s virtually never 100% certainty about anything. You know, as someone once pointed out, gravity is a theory. BROOKS: Gravity is testable, though.. -

Class of 1971 Viking Update

ST. OLAF COLLEGE Class of 1971 – PRESENTS – The Viking Update in celebration of its 50th Reunion Autobiographies and Remembrances stolaf.edu 1520 St. Olaf Avenue, Northfield, MN 55057 Advancement Division 800-776-6523 Student Project Manager Genevieve Hoover ’22 Student Editors Teresa Fawsett ’22 Grace Klinefelter ’23 Student Designers Inna Sahakyan ’23 50th Reunion Staff Members Ellen Draeger Cattadoris ’07 Olivia Snover ’19 Cheri Floren Printing Park Printing Inc., Minneapolis, MN Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in the Viking Update are those of the individual alumni and do not reflect the official policy or position of St. Olaf College. Biographies are not fact-checked for accuracy. 4 CLASS OF 1971 REUNION COMMITTEE REUNION CO-CHAIRS Sally Olson Bracken and Ted Johnson COMMUNICATIONS GIFT COMMITTEE PROGRAM COMMITTEE COMMITTEE CO-CHAIRS CO-CHAIRS CO-CHAIRS Jane Ranzenberger Goldstein Susan Myhre Hayes Natalie Larsen Gehringer Kris Yung Walseth Gudrun Anderson Witrak Mark Hollabaugh Philip Yeagle COMMUNICATIONS GIFT COMMITTEE PROGRAM COMMITTEE COMMITTEE Jane Ranzenberger Goldstein Susan Myhre Hayes Natalie Larsen Gehringer Kris Yung Walseth Gudrun Anderson Witrak Mark Hollabaugh Philip Yeagle Mary Ellen Andersen Bonnie Ohrlund Ericson Sylvia Flo Anshus Barbara Anshus Battenberg Bob Freed Paul Burnett Beth Minear Cavert Michael Garland Robert Chamberlin Kathryn Hosmer Doutt Bob Gehringer Diane Lindgren Forsythe Ann Williams Garwick William Grimbol Dale Gasch John Hager Janice Burnham Haemig Christina Glasoe Mike Holmquist -

Swiss!Climate!Summer!

! ! ! ! 14th!Swiss!Climate!Summer!School! ! Extreme!Events!and!Climate! ! ! Congressi!Stefano!Franscini,!Monte! Verità! ! 23!–!28!August!2015! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Supporting!bodies! ! ! Center!for!Climate!Systems!Modeling! ETH!Zurich! CHN!L12.2! Universitätsstr.!16! CH98092!Zurich! http://www.c2sm.ethz.ch/! ! ! Monte!Verità! ! Via!Collina!! ! CH96612!Ascona! ! http://www.csf.ethz.ch!! ! ! ETH!Zurich! Rämistrasse!101! 8092!Zurich! https://www.ethz.ch! ! ! University!of!Bern! ! Oeschger!Centre! Zähringerstrasse!25! CH93012!Bern! http://www.oeschger.unibe.ch! ! !!!!! Swiss!Reinsurance!Company! ! Mythenquai!50/60! P.O.!Box! CH98022!Zürich! http://www.swissre.com! ! ! Federal!Office!of!Meteorology!and! ! Climatology! Meteoswiss! Operation!Center,!B.O.!Box!257! CH98058!Zurich9Flughafen! http://www.meteoswiss.ch! ! ! The!Global!Energy!and!Water!Cycle! Experiment! http://www.gewex.com! ! ! World!Climate!Research!Programme!! 7bis!Avenue!de!la!Paix,!! Case!postale!2300!Nations! CH91211!Geneva! http://wcrp9climate.org! ! ! ! Table of Contents Cloud Radiative Effect depending on Cloud 1 Aebi Christine Type and Cloud Fraction Exploring the Dynamical Causes of Northeast Agel Laurie 3 US Extreme Precipitation European summer heatwaves and North Alvarez-Castro M. Carmen Atlantic weather regimes in the last 5 Millennium Probabilistic Estimates of Marine N2O Battaglia Gianna 6 Emissions Flood damage claims of houseowners Bernet Daniel promise insights about surface runoff in 8 Switzerland Bevacqua Emanuele Statistical Modelling of Compound Floods 10 Extreme -

Vol. 68(2)-2019 WMO 2030 Vision 2030 WMO Realizing the Realizing The

BULLETINVol. 68 (2) - 2019 WEATHER CLIMATE WATER CLIMATE WEATHER Realizing the WMO 2030 Vision WMO BULLETIN Contents The journal of the World Meteorological Realizing the WMO Vision for 2030: Organization An interview with Secretary-General Petteri Taalas Volume 68 (2) - 2019 By Sylvie Castonguay. 2 Secretary-General P. Taalas Deputy Secretary-General E. Manaenkova Copernicus Joining Forces with WMO on Assistant Secretary-General W. Zhang GFCS The WMO Bulletin is published twice per year By Erica Allis, Jean-Nöel Thépaut, Carlo Buontempo, in English, French, Russian and Spanish editions. Rupa Kumar Kolli, Wilfran Moufouma Okia, Berit Arheimer, Abdu Ali, Joni Dehaspe and Editor E. Manaenkova Christian Birkel . 5 Associate Editor S. Castonguay Editorial board E. Manaenkova (Chair) Sustainability of Atmospheric S. Castonguay (Secretary) P. Kabat (Chief Scientist, research) Observations in Developing Countries R. Masters (policy, external relations) M. Power (development, regional activities) By Paolo Laj, Marcos Andrade, Ranjeet Sokhi, J. Cullmann (water) Y. Adebayo (education and training) Claudia Volosciuk and Oksana Tarasova . .14 F. Belda Esplugues (observing and information systems) Subscription rates Changing Volatile Organic Compound Surface mail Air mail 1 year CHF 30 CHF 43 Emissions in Urban Environments: 2 years CHF 55 CHF 75 Many Paths to Cleaner Air E-mail: [email protected] By Isobel Simpson and Claudia Volosciuk . .22 © World Meteorological Organization, 2018 The right of publication in print, electronic and any other form and in any language is reserved by WMO. Short extracts from WMO publications may be reproduced without authorization, provided that the complete source is clearly indicated. Edito- rial correspondence and requests to publish, reproduce or translate this publication (articles) in part or in whole should be addressed to: Chairperson, Publications Board World Meteorological Organization (WMO) 7 bis avenue de la Paix Tel.: +41 (0) 22 730 8403 P.O. -

A Summary of Flooding Events in Boston

1810 flooding (4-10 fatalities) - http://www.lincolnshirelive.co.uk/200-years-flood-end-floods/story-11195470-detail/story.html the text below from the website does mention Fishtoft and Fosdyke as areas that were affected: "AS many as 10 people may have died during the great flood of 1810, which engulfed the area in the pitch black of night and without warning. The total loss of life has only now been revealed, following research into archived material. Historian Hilary Healey has researched the incident and uncovered details of the deaths, which reveal the body count to be much more than the four believed to have perished. In Fosdyke, a servant girl of farmer Mr Birkett found herself surrounded by the sea in a pasture while milking cows and was washed away. Also in Fosdyke, an elderly woman in the course of the night was washed out of an upper window of her cottage and drowned. At Fishtoft, Mr Smith Jessop, a farmer's son, was drowned while trying to rescue some of his father's sheep. Accounts of the flood are few, but the Stamford Mercury recorded some inquests which may have been held at Boston court. These included a youth, William Green, about 16 years old, who drowned at Fishtoft, another unidentified boy, thought to have been from a fishing boat called the Amber Blay, and John Jackson and William Black, also from a wrecked vessel. Inquests were also held into the deaths of two women from Fosdyke, Esther Tunnard and Ann Burton, drowned by the flood inundating their cottages (one of them may have been the person referred to above). -

Local Flow Conditions in the Bergen Valley Based on Observations And

Local flow conditions in the Bergen valley based on observations and numerical simulations Master Thesis in Meteorology Aslaug Sk˚alevikValved October 2012 ER SI IV T A N U S B E S R I G E N S UNIVERSITY OFBERGEN GEOPHYSICAL INSTITUTE The picture on the front page was taken during field work at the site of the Ulriksbakken Automatic Weather Station in December 2011. Mount Løvstakken is standing tall above the clouds on the opposite side of the Bergen valley. Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude for all help given by my supervisor, Joachim Reuder, throughout this study. His ideas, advices, guidance and particularly all the long hours of work at the end of this project, are highly appreciated. In addition, I would like to thank for the opportunity to work with a subject that is of great interest for me, and for making this a reality. I am also grateful for all the help given by my co-supervisor, Marius Opsanger Jonassen. All technical support from him with WRF and Matlab has been of enormous help. Without his effort, this thesis would not have been as comprehensive as it is now. I would also like to thank for his guidance along the way, his proof-reading at the end, and for including me in his article. Another important contributor to this thesis is Anak Bhandari. I highly appreciate all his work and help with the weather stations and rawdata. It is due to him that this study now has long time series with observations. I am also very glad for being included in the field work, which has been a great experience that I would not have missed out on. -

Atabatic Wind and Oundary Layer Front Eriment Around Reenland ("KABE

atabatic wind and oundary Layer Front eriment around reenland ("KABE einemann Ber. Polarforsch. 269 (1 998) ISSN 01 76 - 5027 Corresponding uuthor uddress: Dr. GüntheHeinemann, Meteorologisches Institut der Universitä Bonn, Auf dem Hüge 20, D 53121 Bonn, Germany. (email: gheinemann @uni-bonn.de) Contents 1.Introduction ........................................................1 1.1Goals ......................................................1 1.2 Participating institutions and pasticipants. acknowledgments ........... 1 1.3 Time schedule of KABEG ......................................2 2 . Scientific background ................................................3 2.1 Katabatic wind ...............................................3 2.2 Boundary layer fronts .........................................8 3 . Experiment setup ...................................................10 3.1 Experimental area ........................................... 10 3.2 Surface stations .............................................10 3.3 Aircraft data ................................................10 3.4 Satellite data ................................................14 4 . First results of the surface stations ......................................16 5 . Overview over the flight missions ......................................21 5.1 Flight strategy ..............................................21 5.2 Summary of the flieht missions .................................23 5.3 A brief description of the katabatic wind flieht missions ............. 25 5.3.1 KAI 18 April 1997 -

PROJECTS • REPORTS • Resources • ARTICLES • REVIEWS EXECUTIVE 2011

wine making Volume 43 No 2 2011 In this issue: Birthing Kits: Mackellar Girls’ High School ................ 6 January 2011: Learning using Twitter .......................16 Earth Strikes Back – Natural disasters 2010–2011 .........19 Japan – Earthquake, tsunami & nuclear crises......23 United Nations International Year of Forests ....................31 Poverty on our doorstep – East Timor .......................48 PROJECTS • REPORTS • resources • ARTICLES • REVIEWS EXECUTIVE 2011 PRESIDENT Mr Nick Hutchinson, Macquarie University VICE PRESIDENTS Ms Lorraine Chaffer, Gorokan High School Dr Grant Kleeman, Macquarie University Ms Sharon McLean, St Ignatius College Riverview HONORARY SECRETARY (Acting) Ms Pam Gregg, Education Consultant MINUTE SECRETARY Mr Paul Alger, Retired HONORARY TREASURER Dr Grant Kleeman, Macquarie University EDITORS Dr Susan Bliss, Editor, Macmillan Publishers Dr Grant Kleeman, Macquarie University OFFICE OF THE GEOGRAPHY TEACHERS’ ASSOCIATION COUNCILLORS OF NEW SOUTH WALES Dr Susan Bliss, Editor, Macmillan Publishers ABN 59246850128 Mr Milton Brown, SurfAid International Address: Block B, Leichhardt Public School Grounds, 101–105 Norton Street, (Cnr. Norton & Marion Streets) Mr Robert Gandiaga, Casula High School Leichhhardt NSW 2040 Mrs Barbara Heath, Retired Postal Address: PO Box 577 Mr Keith Hopkins, St Mary Star of the Sea Leichhardt, NSW, 2040, Australia College, Wollongong Telephone: (02) 9564 3322, Fax: (02) 9564 2342 Mr John Lewis, Narara Valley High School Website: www.gtansw.org.au Email: [email protected] -

Bibliography

The AAG John Russell Mather and Sandra Pritchard Mather Climatology Knowledge Environment Bibliography The document is organized in reverse chronological order. Use the Bookmarks menu to navigate to each year. Entries are listed alphabetically by last name within each section. Last update: August 2012 For more recent information since this date, please go to http://community.aag.org/cke 2012 Kahan, Dan M., Ellen Peters, Maggie Wittlin, Paul Slovic, Lisa Larrimore Ouellette, Donald Braman, and Gregory Mandel. 2012. “The Polarizing Impact of Science and Literacy and Numeracy on Perceived Climate Change Risks.” Nature Climate Change. http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ nclimate1547.html. McKibben, Bill. 2012. The Global Warming Reader: a Century of Writing About Climate Change. New York: Penguin Books. Ornstein, Norman J., Michael Oppenheimer, and Jon A. Krosnick. 2012. “Climate Policy: Public Perception, Science, and the Political Landscape” 902 Hart Building. Rosenzweig, Cynthia, Cesar Izarrald, Paul Gepts, and Gerald Nelson. 2012. “Climate Change and Agriculture: Food and Farming in a Changing Climate” 328A Senate Russell & 2318 Rayburn House. Titley, David, Jeffrey Mazo, and Paul Higgins. 2012. “Climate Change & National Security” 2212 Rayburn. The AAG John Russell Mather and Sandra Pritchard Mather Climatology Knowledge Environment http://community.aag.org/CKE 2011 Abeysirigunawardena, D.S., D.J. Smith, and B. Taylor. 2011. “Extreme Sea Surge Responses to Climate Variability in Coastal British Columbia, Canada.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 101: 992–1010. Anon. 2011a. National Action Plan: Priorities for Managing Freshwater Resources in a Changing Climate. Action Plan. Interagency Climate Change Adaptation Task Force. ———. 2011b. -

Amherst Today

ALSO INSIDE FALL The 1896 alum 2017 who unearthed our mammoth skeleton is still frustrating and surprising scientists Amherst today. As the College’s first Army ROTC FUTURE student in two decades, Rebecca Segal ’18 is part of the long, rich, VETERAN complex story of Amherst and the military. XXIN THIS ISSUE: FALL 2017XX 20 28 36 Veterans’ Loomis “The Splendor of Days Illuminated Mere Being” FROM THE CIVIL WAR TO AN THE PROFESSOR WHO THE COLLEGE REMEMBERS “ACADEMIC BOOT CAMP” UNEARTHED AMHERST’S ACCLAIMED POET AND THIS SUMMER, AMHERST’S MAMMOTH SKELETON IN LECTURER RICHARD HISTORY OF TEACHING 1923 IS STILL FRUSTRATING WILBUR ’42, WHO DIED MEMBERS OF THE MILITARY AND SURPRISING THIS FALL. BY KATHARINE SCIENTISTS TODAY. BY KATHARINE WHITTEMORE BY GEOFFREY GILLER ’10 WHITTEMORE Inside the College’s Beneski Museum, a local scientist realized that this Tyrannosaurid jaw is different from any other he’s seen. (And he has seen quite a few.) Page 28 Photograph by GEOFFREY GILLER ’10 2 “We take pleasure in First Words A career in pediatric cardiology seeing the impossible inspires a young adult novel. appear possible, and the 4 invisible appear visible.” Voices Readers consider such far-reaching Historian Thomas W. Laqueur, invited to Amherst as issues as China’s one-child policy, a Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar, during his October nuclear war and the search for lecture on how and why the living care for and extraterrestrial life. remember the dead. PAGE 12 6 College Row Support after Hurricane Maria, XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX researching bodily bacteria, Amherst’s “single finest graduate” News Video & Audio and more Jeffrey C.