Japanese Women and Sport: Beyond Baseball and Sumo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shoes Approved by World Athletics - As at 01 October 2021

Shoes Approved by World Athletics - as at 01 October 2021 1. This list is primarily a list concerns shoes that which have been assessed by World Athletics to date. 2. The assessment and whether a shoe is approved or not is determined by several different factors as set out in Technical Rule 5. 3. The list is not a complete list of every shoe that has ever been worn by an athlete. If a shoe is not on the list, it can be because a manufacturer has failed to submit the shoe, it has not been approved or is an old model / shoe. Any shoe from before 1 January 2016 is deemed to meet the technical requirements of Technical Rule 5 and does not need to be approved unless requested This deemed approval does not prejudice the rights of World Athletics or Referees set out in the Rules and Regulations. 4. Any shoe in the list highlighted in blue is a development shoe to be worn only by specific athletes at specific competitions within the period stated. NON-SPIKE SHOES Shoe Company Model Track up to 800m* Track from 800m HJ, PV, LJ, SP, DT, HT, JT TJ Road* Cross-C Development Shoe *not including 800m *incl. track RW start date end date ≤ 20mm ≤ 25mm ≤ 20mm ≤ 25mm ≤ 40mm ≤ 25mm 361 Degrees Flame NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Adios 3 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios 4 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios 5 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios 6 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios Pro NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 2 NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Boston 8 NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Boston 9 NO NO NO -

Actlaa Best Performance Records

ACTLAA BEST PERFORMANCE RECORDS Note: Due to the use of Electronic Timing at ACTLAA carnivals held at Bruce Stadium, the following Track Event Records have been standardised. This means that where only a Hand Held record performance is available, this result is standardised to Electronic Timing by adding 0.24 seconds up to 300metres and .14 for 400m (ie 10 seconds Hand Held is equivalent to 10.24 seconds Standardised - "10.24s/S"). EVENT ATHLETE PERFORMANCE CENTRE DATE EVENT ATHLETE PERFORMANCE CENTRE DATE U/7 BOYS U/7 GIRLS Long Jump M.Beckenham 3.70m Qbn 1983 Long Jump M.Kelly 3.38m Qbn Feb-95 Shot Put (1kg) K.Kouparitsas 8.85m Cor Mar-94 Shot Put (1kg) S. Rauraa 7.33m Gin Nov-16 U/8 BOYS U/8 GIRLS 50 Metres J.Pilliner 8.04s/S Gin Mar-91 50 Metres G. O'Rourke 8.10s/E Wod Mar-03 70 Metres T.Harper 10.34s/S Wes 1978 70 Metres K.McDonald 11.04s/S Bel Mar-90 100 Metres T.Harper 14.24s/S Wes 1978 100 Metres G. O'Rourke 15.59s/E Wod Mar-03 200 Metres D.Toohey 30.64s/S Wes Mar-87 200 Metres K.Smith 31.64s/S Wod 1980 60 M Hurdles J. Tsekenis 11.52s/E Wes Apr-05 60 M Hurdles V. Chard 11.45s/E Qbn Mar-03 Long Jump M.Beckenham 4.05m Qbn 1984 Long Jump M.Kelly 4.07m Qbn Mar-96 Shot Put (1.5kg) K.Kouparitsas 9.77m Cor Feb-95 Shot Put (1.5kg) S. -

January 2016 Issue 317

January 2016 Issue 317 Ladies Surrey County team, at Denbies Ladies Surrey League, at Reigate Priory 1 In this issue page Editorial 3 Cross Country Roundup 4 Greenbelt Relay 9 Welsh Castles Relay 11 Stragglers Profile: Malcolm Davies 13 Nigel Rothwell reflects on the past 12 months 15 The Importance of Winter hydration 19 WALK – Going the Distance 21 Portsmouth Ultra Marathon report 22 Kingston Physiotherapy – 15% off for Stragglers 25 Cabbage Patch 4 Results 26 Cross country skiing trip to Germany 28 Stragglers and Richmond Bridge Boat Club Race 30 Future Race Dates 31 2 Editorial Welcome to the first Stragmag of 2016! There an was excellent end to 2015 – convincing victory in the mob match against 26.2, and a well-attended pub crawl, and an equally good start to 2016 – a great turn out for the New Year’s Day run and New Year party at the Hampton Hill Cricket Club. Many Strags are well into their marathon training and the latest initiative from the club’s training group – improve your 5k – is proving popular. The cross country season has one more set of league fixtures with our men’s team well placed for promotion. This issue has a roundup of recent XC activity for men, ladies and juniors. We’re also already turning our attention to the summer relays, with Green Belt and Welsh Castles teams already being organised. Having completed profiles of committee members, I’m now focusing on members who make an important contribution to an aspect of club life and with Welsh Castles in mind it’s the turn of men’s team organiser Malcolm Davies. -

Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia Annual Report 2010–2011 Contents

Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia Annual Report Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia 2010–2011 2010–2011 Annual Report Contents From the President 4 From the Chief Executive Officers 6 From The Australian Sports Commission 8 High Performance 10 High Performance Pathways Program 14 Competitions 16 Marketing and Communications 18 Coach Development 22 Running Australia 26 Life Governors/Members and Merit Award Holders 27 Australian Honours List 35 Vale 36 Registration & Participation 38 Australian Records 40 Australian Medalists 41 Athletics ACT 44 Athletics New South Wales 46 Athletics Northern Territory 48 Queensland Athletics 50 Athletics South Australia 52 Athletics Tasmania 54 Athletics Victoria 56 Athletics Western Australia 58 Australian Olympic Committee 60 Australian Paralympic Committee 62 Financial Report 64 Chief Financial Officer’s Report 66 Directors’ Report 72 Auditors Independence Declaration 76 Income Statement 77 Statement of Comprehensive Income 78 Statement of Financial Position 79 Statement of Changes in Equity 80 Cash Flow Statement 81 Notes to the Financial Statements 82 Directors’ Declaration 103 Independent Audit Report 104 Trust Funds 107 Staff 108 Commissions and Committees 109 2 ATHLETICS AuSTRALIA ANNuAL Report 2010 –2011 | SuCCESS ON THE WORLD STAGE 3 From the President Chief Executive Dallas O’Brien now has his field in our region. The leadership and skillful feet well and truly beneath the desk and I management provided by Geoff and Yvonne congratulate him on his continued effort to along with the Oceania Council ensures a vast learn the many and numerous functions of his array of Athletics programs can be enjoyed by position with skill, patience and competence. -

Lesson Plans Introduction the Following Section Provides Twenty-Seven Ready-To-Implement Lesson Plans for Teachers

Lesson Plans Introduction The following section provides twenty-seven ready-to-implement lesson plans for teachers. The section is divided into four smaller sub-sections. • Early Stage 1 (5 year olds) • Stage 1 (6/7 year olds) • Stage 2 (8/9 year olds) • Stage 3 (10 years and LAANSWabove) ASAP Level 3 Each sub-section contains lesson plans suitable for children in these age groups. The lesson plans assume classes of up to thirty students and a time limit of 30-45 minutes, however a teacher can adapt the ideas to suit their particular circumstances. Each lesson plan generally follows the same format, being: Aim; Equipment; Warm Up; Skill Development; Games. In relevant places, topics such as safety aspects and various hints that will help the teacher organise and conduct a successful lesson are included. The lesson plans at times assume prior learning, ie. that the children have participated in the skill development activities contained in preceding lessons designed for the earlier levels. The activities featured in the lesson plans are based on fun, skill development, maximum group participation and a sound, logical progression. The lesson plans form the foundation of a class athletics unit. 3 29 Early Stage 1 Lesson Plans • Running - Lesson 1 - Lesson 2 • Jumping - Lesson 1 - LessonLAANSW 2 ASAP Level 3 • Throwing - Lesson 1 - Lesson 2 30 Early Stage 1 Running Lesson Plan Lesson 1 Introduction to basic running technique Introduction to relays Ground markers x 30 Relay batons x 5 Warm Up 1. Group Game: "Signals" LAANSW ASAP Level 3 Set up a playing area with ground markers. -

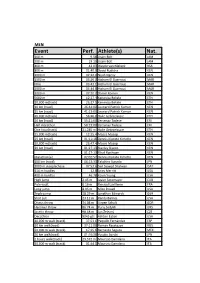

Event Perf. Athlete(S) Nat

MEN Event Perf. Athlete(s) Nat. 100 m 9.58 Usain Bolt JAM 200 m 19.19 Usain Bolt JAM 400 m 43.03 Wayde van Niekerk RSA 800 m 01:40.9 David Rudisha KEN 1000 m 02:12.0 Noah Ngeny KEN 1500 m 03:26.0 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR Mile 03:43.1 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 2000 m 04:44.8 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 3000 m 07:20.7 Daniel Komen KEN 5000 m 12:37.4 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 10,000 m(track) 26:17.5 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 10 km (road) 26:44:00 Leonard Patrick Komon KEN 15 km (road) 41:13:00 Leonard Patrick Komon KEN 20,000 m(track) 56:26.0 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 20 km (road) 55:21:00 Zersenay Tadese ERI Half marathon 58:23:00 Zersenay Tadese ERI One hour(track) 21,285 m Haile Gebrselassie ETH 25,000 m(track) 12:25.4 Moses Mosop KEN 25 km (road) 01:11:18 Dennis Kipruto Kimetto KEN 30,000 m(track) 26:47.4 Moses Mosop KEN 30 km (road) 01:27:13 Stanley Biwott KEN 01:27:13 Eliud Kipchoge KEN Marathon[a] 02:02:57 Dennis Kipruto Kimetto KEN 100 km (road) 06:13:33 Takahiro Sunada JPN 3000 m steeplechase 07:53.6 Saif Saaeed Shaheen QAT 110 m hurdles 12.8 Aries Merritt USA 400 m hurdles 46.78 Kevin Young USA High jump 2.45 m Javier Sotomayor CUB Pole vault 6.16 m Renaud Lavillenie FRA Long jump 8.95 m Mike Powell USA Triple jump 18.29 m Jonathan Edwards GBR Shot put 23.12 m Randy Barnes USA Discus throw 74.08 m Jürgen Schult GDR Hammer throw 86.74 m Yuriy Sedykh URS Javelin throw 98.48 m Jan Železný CZE Decathlon 9045 pts Ashton Eaton USA 10,000 m walk (track) 37:53.1 Paquillo Fernández ESP 10 km walk(road) 37:11:00 Roman Rasskazov RUS 20,000 m walk (track) 17:25.6 Bernardo -

Keymaze 500 Keymaze 700 Documentation

KEYMAZE 500 KEYMAZE 700 DOCUMENTATION 1 / Getting started 1.1.Product description USB cable connection. When plugging in the cable, be sure to turn the connector round the right way. The metal cable guide pin must be able to slide freely into the hole to the bottom-right of the socket. PC-Keymaze connecting cable Heart strap (Keymaze 700 only) Changing the strap Equipment needed i The strap and tool may differ slightly depending on the date when you buy your Keymaze. 2 - Procedure Using the tool supplied, remove the strap. To do this, you need to release the pins connecting the strap to the Keymaze casing. Insert the tool between the strap's attachment points and the strap. You need to lever down so that the spring in the pin compresses: the strap detaches. Take the new strap and put the pin into the casing at the top of the strap. Position the pin in one of the holes in the watch. Using the tool, compress the spring in the pin and position the pin in the other hole. If the pin is correctly positioned in both holes, the strap is correctly attached. You can then pull gently on the strap to check that it is firmly attached. i If you have trouble changing the strap, we advise you to visit the workshop at your nearest DECATHLON store. A technician will help you to change it. 1.2.first use 1.2.1. Charging your Keymaze This wrist GPS uses a 750 mAh Lithium-Ion battery. You should charge it fully before first using it. -

FINA Open Water Swimming Manual 2020 Edition

Open Water Swimming Manual 2020 Edition Published by FINA Office Chemin de Bellevue 24a/24b CH - 1005 Lausanne SWITZERLAND FINA Open Water Swimming Manual 2020 Edition FINA BUREAU MEMBERS 2017-2021 PRESIDENT: Dr Julio C. Maglione (URU) FIRST VICE PRESIDENT: (ASIA) Mr Husain Al Musallam (KUW) SECOND VICE PRESIDENT: (AFRICA) Mr Sam Ramsamy (RSA) HONORARY TREASURER: Mr Pipat Paniangvait (THA) VICE PRESIDENTS: (AMERICAS) Mr Dale Neuburger (USA) (EUROPE) Mr Paolo Barelli (ITA) (OCEANIA) Mr Matthew Dunn (AUS) MEMBERS: Mr Khaleel Al-Jabir (QAT) Mr Taha Sulaiman Dawood Al Kishry (OMA) Mr Algernon Cargill (BAH) Mr Errol Clarke (BAR) Mr Dimitris Diathesopoulos (GRE) Dr Mohamed Diop (SEN) Mr Zouheir El Moufti (MAR) Mr Mario Fernandes (ANG) Mr Tamas Gyarfas (HUN) Ms Penny Heyns (RSA) Mr Andrey Kryukov (KAZ) Dr Margo Mountjoy (CAN) Mr Juan Carlos Orihuela Garcete (PAR) Dr Donald Rukare (UGA) Mr Vladimir Salnikov (RUS) Mr Daichi Suzuki (JPN) Mr Erik van Heijningen (NED) Ms Jihong Zhou (CHN) HONORARY LIFE PRESIDENT: Mr Mustapha Larfaoui (ALG) HONORARY MEMBERS: Mr Gennady Aleshin (RUS) Mr Rafael Blanco (ESP) Mr Bartolo Consolo (ITA) Mr Eldon C. Godfrey (CAN) Mr Nory Kruchten (LUX) Mr Francis Luyce (FRA) Page 2 FINA Open Water Swimming Manual 2020 Edition Mr Guillermo Martinez (CUB) Mr Gunnar Werner (SWE) EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mr Cornel Marculescu 2017-2021 FINA Technical Open Water Swimming Committee Bureau Liaison: Mr Zouheir ELMOUFTI (MAR) Chairman: Mr Ronnie Wong Man Chiu (HKG) Vice Chairman: Mr Stephan Cassidy (USA) Honorary Secretary: Mr Samuel Greetham -

HEEL and TOE ONLINE the Official Organ of the Victorian Race Walking

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2019/2020 Number 40 Tuesday 30 June 2020 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours: Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Runners-World/235649459888840 VRWC COMPETITION RESTARTS THIS SATURDAY Here is the big news we have all been waiting for. Our VRWC winter roadwalking season will commence on Saturday afternoon at Middle Park. Club Secretary Terry Swan advises the the club committee meet tonight (Tuesday) and has given the green light. There will be 3 Open races as follows VRWC Roadraces, Middle Park, Saturday 6th July 1:45pm 1km Roadwalk Open (no timelimit) 2.00pm 3km Roadwalk Open (no timelimit) 2.30pm 10km Roadwalk Open (timelimit 70 minutes) Each race will be capped at 20 walkers. Places will be allocated in order of entry. No exceptions can be made for late entries. $10 per race entry. Walkers can only walk in ONE race. Multiple race entries are not possible. Race entries close at 6PM Thursday. No entries will be allowed on the day. You can enter in one of two ways • Online entry via the VRWC web portal at http://vrwc.org.au/wp1/race-entries-2/race-entry-sat-04jul20/. We prefer payment by Credit Card or Paypal within the portal when you register. Ignore the fact that the portal says entries close at 10PM on Wednesday. -

Ontario Masters Indoor Records

CURRENT RECORD EVENT MF AGE TIME DISTANCE FIRSTNAME LASTNAME DATE WHERE C 1500 Metres M35 1500 Metres Ray Tucker C 1500 Metres M40 1500 Metres Dave Stewart 1500 Metres M45 1500 Metres Ron Frid 1994 C 1500 Metres M45 1500 Metres Jay Brecher 30-March-2019 WMA Championships, Torun, POL 1500 Metres M50 1500 Metres Benjamin Johns 1500 Metres M50 4:18.43 1500 Metres Paul Osland 16-March-2014 CMA Champs, TTFC, Toronto, ON C 1500 Metres M50 4:16.90 1500 Metres Paul Osland March, 2014 WMA Indoor Champs, Budapest, HU 1500 Metres M55 1500 Metres Ed Whitlock 1987 1500 Metres M55 4:35.03 1500 Metres Jerry Kooymans 07-Jan-2013 Sharon Anderson, U of Toronto, Toronro, ON C 1500 Metres M55 4:26.22 1500 Metres Stuart Galloway 14-February-2016 AO Youth-Senior Champs, TTFC, Toronto, ON C 1500 Metres M60 1500 Metres Earl Fee C 1500 Metres M65 1500 Metres Earl Fee C 1500 Metres M70 1500 Metres Ed Whitlock C 1500 Metres M75 1500 Metres Ed Whitlock 1500 Metres M80 1500 Metres Robert Comber Indoor Championships C 1500 Metres M80 1500 Metres Ed Whitlock 19-March-2011 Canadian Indoor Champs Kamloops 2011 C 1500 Metres M85 6:38.87 1500 Metres Ed Whitlock 19-March-2016 CMA Championships, TTFC, Toronto, ON C 1500 Metres W35 1500 Metres Janet Takahashi 1500 Metres W40 1500 Metres Linda Findlay Indoor Championships C 1500 Metres W40 4:32.43 1500 Metres Mary Unsworth 25-February-2018 OMA Champs, TTFC, Toronto, ON 1500 Metres W45 1500 Metres Christine Lavalee C 1500 Metres W45 1500 Metres Annie Bunting March, 2010 WMA Indoor Champs Kamloops, BC C 1500 Metres W50 1500 Metres -

The Manual for Streets: Evidence and Research

The Manual for Streets: evidence and research Prepared for Traffic Management Division, Department for Transport I York, A Bradbury, S Reid, T Ewings and R Paradise TRL Report TRL661 First Published 2007 ISSN 0968-4107 ISBN 1-84608-660-4 Copyright Transport Research Laboratory, 2007. This report has been produced by TRL Limited, under/as part of a contract placed by the Department for Transport. Any views expressed in it are not necessarily those of the Department. TRL is committed to optimising energy efficiency, reducing waste and promoting recycling and re-use. In support of these environmental goals, this report has been printed on recycled paper, comprising 100% post-consumer waste, manufactured using a TCF (totally chlorine free) process. ii CONTENTS Page Executive Summary 1 Acronyms 3 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Manual for Streets 5 1.2 Design Bulletin 32 6 1.3 Underlying research 6 1.4 Report structure 6 2 Review of existing literature 7 3 Site selection and measurement 9 3.1 Site selection 9 3.2 CAD measurements 9 3.3 Site surveys 11 4 Speeds and geometry data site ranges 11 4.1 Outliers 12 4.2 Variation within the data 13 5 Speed adaptation 15 5.1 Link speeds 15 5.2 Junction speeds 16 6 Modelled safety impacts 18 6.1 Braking modelling 18 6.2 Stopping distances on links 18 6.3 Stopping distances at junctions 19 6.4 Implications of modelled situations 20 7 Observed safety 21 7.1 Belgravia 21 7.2 Accidents at junctions 22 7.3 Accidents on links 23 8 Household survey 24 8.1 Sampling 24 8.2 Sample composition 25 iii Page 9 Residents opinions 26 9.1 Streetscape 26 9.2 Parking 27 9.2.1 Car use and off-street parking 27 9.2.2 Parking problems 28 9.2.3 Parked vehicles 28 9.2.4 Respondents’ issues with parking in their street 29 9.3 Main safety concerns 30 9.4 Road safety 31 9.4.1 Walking and cycling safety 32 9.4.2 Safety of children 32 9.4.3 Improving road safety in residential streets 33 9.5 Accidents 33 9.6 Non-motorised vs. -

Biological Determinants of Track and Field Throwing Performance

Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology Review Biological Determinants of Track and Field Throwing Performance Nikolaos Zaras 1,*, Angeliki-Nikoletta Stasinaki 2 and Gerasimos Terzis 2 1 Human Performance Laboratory, Department of Life and Health Sciences, University of Nicosia, Nicosia 1700, Cyprus 2 Sports Performance Laboratory, School of Physical Education and Sport Science, University of Athens, 17237 Athens, Greece; [email protected] (A.-N.S.); [email protected] (G.T.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +357-22842318; Fax: +357-22842399 Abstract: Track and field throwing performance is determined by a number of biomechanical and biological factors which are affected by long-term training. Although much of the research has focused on the role of biomechanical factors on track and field throwing performance, only a small body of scientific literature has focused on the connection of biological factors with competitive track and field throwing performance. The aim of this review was to accumulate and present the current literature connecting the performance in track and field throwing events with specific biological factors, including the anthropometric characteristics, the body composition, the neural activation, the fiber type composition and the muscle architecture characteristics. While there is little published information to develop statistical results, the results from the current review suggest that major biological determinants of track and field throwing performance are the size of lean body mass, the neural activation of the protagonist muscles during the throw and the percentage of type II muscle fiber cross-sectional area. Long-term training may enhance these biological factors and possibly Citation: Zaras, N.; Stasinaki, A.-N.; lead to a higher track and field throwing performance.