The Manual for Streets: Evidence and Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

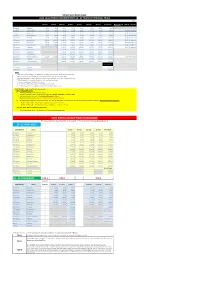

Actlaa Best Performance Records

ACTLAA BEST PERFORMANCE RECORDS Note: Due to the use of Electronic Timing at ACTLAA carnivals held at Bruce Stadium, the following Track Event Records have been standardised. This means that where only a Hand Held record performance is available, this result is standardised to Electronic Timing by adding 0.24 seconds up to 300metres and .14 for 400m (ie 10 seconds Hand Held is equivalent to 10.24 seconds Standardised - "10.24s/S"). EVENT ATHLETE PERFORMANCE CENTRE DATE EVENT ATHLETE PERFORMANCE CENTRE DATE U/7 BOYS U/7 GIRLS Long Jump M.Beckenham 3.70m Qbn 1983 Long Jump M.Kelly 3.38m Qbn Feb-95 Shot Put (1kg) K.Kouparitsas 8.85m Cor Mar-94 Shot Put (1kg) S. Rauraa 7.33m Gin Nov-16 U/8 BOYS U/8 GIRLS 50 Metres J.Pilliner 8.04s/S Gin Mar-91 50 Metres G. O'Rourke 8.10s/E Wod Mar-03 70 Metres T.Harper 10.34s/S Wes 1978 70 Metres K.McDonald 11.04s/S Bel Mar-90 100 Metres T.Harper 14.24s/S Wes 1978 100 Metres G. O'Rourke 15.59s/E Wod Mar-03 200 Metres D.Toohey 30.64s/S Wes Mar-87 200 Metres K.Smith 31.64s/S Wod 1980 60 M Hurdles J. Tsekenis 11.52s/E Wes Apr-05 60 M Hurdles V. Chard 11.45s/E Qbn Mar-03 Long Jump M.Beckenham 4.05m Qbn 1984 Long Jump M.Kelly 4.07m Qbn Mar-96 Shot Put (1.5kg) K.Kouparitsas 9.77m Cor Feb-95 Shot Put (1.5kg) S. -

January 2016 Issue 317

January 2016 Issue 317 Ladies Surrey County team, at Denbies Ladies Surrey League, at Reigate Priory 1 In this issue page Editorial 3 Cross Country Roundup 4 Greenbelt Relay 9 Welsh Castles Relay 11 Stragglers Profile: Malcolm Davies 13 Nigel Rothwell reflects on the past 12 months 15 The Importance of Winter hydration 19 WALK – Going the Distance 21 Portsmouth Ultra Marathon report 22 Kingston Physiotherapy – 15% off for Stragglers 25 Cabbage Patch 4 Results 26 Cross country skiing trip to Germany 28 Stragglers and Richmond Bridge Boat Club Race 30 Future Race Dates 31 2 Editorial Welcome to the first Stragmag of 2016! There an was excellent end to 2015 – convincing victory in the mob match against 26.2, and a well-attended pub crawl, and an equally good start to 2016 – a great turn out for the New Year’s Day run and New Year party at the Hampton Hill Cricket Club. Many Strags are well into their marathon training and the latest initiative from the club’s training group – improve your 5k – is proving popular. The cross country season has one more set of league fixtures with our men’s team well placed for promotion. This issue has a roundup of recent XC activity for men, ladies and juniors. We’re also already turning our attention to the summer relays, with Green Belt and Welsh Castles teams already being organised. Having completed profiles of committee members, I’m now focusing on members who make an important contribution to an aspect of club life and with Welsh Castles in mind it’s the turn of men’s team organiser Malcolm Davies. -

Keymaze 500 Keymaze 700 Documentation

KEYMAZE 500 KEYMAZE 700 DOCUMENTATION 1 / Getting started 1.1.Product description USB cable connection. When plugging in the cable, be sure to turn the connector round the right way. The metal cable guide pin must be able to slide freely into the hole to the bottom-right of the socket. PC-Keymaze connecting cable Heart strap (Keymaze 700 only) Changing the strap Equipment needed i The strap and tool may differ slightly depending on the date when you buy your Keymaze. 2 - Procedure Using the tool supplied, remove the strap. To do this, you need to release the pins connecting the strap to the Keymaze casing. Insert the tool between the strap's attachment points and the strap. You need to lever down so that the spring in the pin compresses: the strap detaches. Take the new strap and put the pin into the casing at the top of the strap. Position the pin in one of the holes in the watch. Using the tool, compress the spring in the pin and position the pin in the other hole. If the pin is correctly positioned in both holes, the strap is correctly attached. You can then pull gently on the strap to check that it is firmly attached. i If you have trouble changing the strap, we advise you to visit the workshop at your nearest DECATHLON store. A technician will help you to change it. 1.2.first use 1.2.1. Charging your Keymaze This wrist GPS uses a 750 mAh Lithium-Ion battery. You should charge it fully before first using it. -

FINA Open Water Swimming Manual 2020 Edition

Open Water Swimming Manual 2020 Edition Published by FINA Office Chemin de Bellevue 24a/24b CH - 1005 Lausanne SWITZERLAND FINA Open Water Swimming Manual 2020 Edition FINA BUREAU MEMBERS 2017-2021 PRESIDENT: Dr Julio C. Maglione (URU) FIRST VICE PRESIDENT: (ASIA) Mr Husain Al Musallam (KUW) SECOND VICE PRESIDENT: (AFRICA) Mr Sam Ramsamy (RSA) HONORARY TREASURER: Mr Pipat Paniangvait (THA) VICE PRESIDENTS: (AMERICAS) Mr Dale Neuburger (USA) (EUROPE) Mr Paolo Barelli (ITA) (OCEANIA) Mr Matthew Dunn (AUS) MEMBERS: Mr Khaleel Al-Jabir (QAT) Mr Taha Sulaiman Dawood Al Kishry (OMA) Mr Algernon Cargill (BAH) Mr Errol Clarke (BAR) Mr Dimitris Diathesopoulos (GRE) Dr Mohamed Diop (SEN) Mr Zouheir El Moufti (MAR) Mr Mario Fernandes (ANG) Mr Tamas Gyarfas (HUN) Ms Penny Heyns (RSA) Mr Andrey Kryukov (KAZ) Dr Margo Mountjoy (CAN) Mr Juan Carlos Orihuela Garcete (PAR) Dr Donald Rukare (UGA) Mr Vladimir Salnikov (RUS) Mr Daichi Suzuki (JPN) Mr Erik van Heijningen (NED) Ms Jihong Zhou (CHN) HONORARY LIFE PRESIDENT: Mr Mustapha Larfaoui (ALG) HONORARY MEMBERS: Mr Gennady Aleshin (RUS) Mr Rafael Blanco (ESP) Mr Bartolo Consolo (ITA) Mr Eldon C. Godfrey (CAN) Mr Nory Kruchten (LUX) Mr Francis Luyce (FRA) Page 2 FINA Open Water Swimming Manual 2020 Edition Mr Guillermo Martinez (CUB) Mr Gunnar Werner (SWE) EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mr Cornel Marculescu 2017-2021 FINA Technical Open Water Swimming Committee Bureau Liaison: Mr Zouheir ELMOUFTI (MAR) Chairman: Mr Ronnie Wong Man Chiu (HKG) Vice Chairman: Mr Stephan Cassidy (USA) Honorary Secretary: Mr Samuel Greetham -

Ontario Masters Indoor Records

CURRENT RECORD EVENT MF AGE TIME DISTANCE FIRSTNAME LASTNAME DATE WHERE C 1500 Metres M35 1500 Metres Ray Tucker C 1500 Metres M40 1500 Metres Dave Stewart 1500 Metres M45 1500 Metres Ron Frid 1994 C 1500 Metres M45 1500 Metres Jay Brecher 30-March-2019 WMA Championships, Torun, POL 1500 Metres M50 1500 Metres Benjamin Johns 1500 Metres M50 4:18.43 1500 Metres Paul Osland 16-March-2014 CMA Champs, TTFC, Toronto, ON C 1500 Metres M50 4:16.90 1500 Metres Paul Osland March, 2014 WMA Indoor Champs, Budapest, HU 1500 Metres M55 1500 Metres Ed Whitlock 1987 1500 Metres M55 4:35.03 1500 Metres Jerry Kooymans 07-Jan-2013 Sharon Anderson, U of Toronto, Toronro, ON C 1500 Metres M55 4:26.22 1500 Metres Stuart Galloway 14-February-2016 AO Youth-Senior Champs, TTFC, Toronto, ON C 1500 Metres M60 1500 Metres Earl Fee C 1500 Metres M65 1500 Metres Earl Fee C 1500 Metres M70 1500 Metres Ed Whitlock C 1500 Metres M75 1500 Metres Ed Whitlock 1500 Metres M80 1500 Metres Robert Comber Indoor Championships C 1500 Metres M80 1500 Metres Ed Whitlock 19-March-2011 Canadian Indoor Champs Kamloops 2011 C 1500 Metres M85 6:38.87 1500 Metres Ed Whitlock 19-March-2016 CMA Championships, TTFC, Toronto, ON C 1500 Metres W35 1500 Metres Janet Takahashi 1500 Metres W40 1500 Metres Linda Findlay Indoor Championships C 1500 Metres W40 4:32.43 1500 Metres Mary Unsworth 25-February-2018 OMA Champs, TTFC, Toronto, ON 1500 Metres W45 1500 Metres Christine Lavalee C 1500 Metres W45 1500 Metres Annie Bunting March, 2010 WMA Indoor Champs Kamloops, BC C 1500 Metres W50 1500 Metres -

Swim Serpentine Training Plans

Swim Serpentine Training Plans To swim one mile in a 25 metre pool you'll need to complete 64 lengths. If you're new to swimming, or are looking to improve, find out if there are any adult swimming sessions in your pool, perhaps a triathlon club or ‘Masters’ training session. These sessions are often welcoming and a great way to progress quickly. Often they also have a swimming coach on the pool side to provide set sessions for you, which can help with your technique. A swimming session should consist of a Warm up, Main Set, Contrast Set and Warm Down: Warm up: Gradually warm up your arms and lungs as you increase your pace over some short distances. Main Set: Typically a target distance broken down into shorter distances with short recovery times to help you work on your pace. For example: the target may be 1000 metres, so a simple session would be to swim 10 x 100 metres with one-minute rest between each four lengths (in a 25m pool). This way you can swim faster for the duration of the 100 metres than you would be able to over a straight 1000m swim. Contrast Set: After a main session the contrast set throws in some drills with perhaps some kick or stroke work. Warm down: A reverse of the Warm up, reduce your speed and think about technique. At other times you may go into the pool to complete a long distance swim, for example, to swim one mile non-stop and time yourself. One-mile pool training plan Train for Swim Serpentine using the following sample sets and drill suggestions. -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

V1 DRAFT 2021 Boys Qualifying and Extra Qualifying Times.Xlsx

School Sport South Coast 2021 QUALIFYING STANDARDS (BOYS 10 - 19 YEARS) for REGIONAL TRIALS V1 Column1 Column2 10 Years 11 Years 12 Years 13 Years 14 Years 15 Years 16 Years 17-19 Years Multi-Class 13 – 15 & 16 – 19 Years 50 metres Freestyle 40.50 38.50 35.50 31.50 30.00 29.00 28.50 28.50 50 metres Breaststroke 51.50 48.50 45.50 41.00 38.50 37.50 37.00 37.00 No QT at Regionals 50 metres Backstroke 48.50 45.50 42.50 37.00 35.50 34.50 34.00 33.50 No QT at Regionals 50 metres Butterflystroke 45.50 42.50 40.50 34.00 33.00 31.50 31.00 30.50 No QT at Regionals 100 metres Freestyle 1:27.00 1:22.00 1:18.00 1:08.00 1:06.00 1:04.00 1:03.00 1:02.50 No QT at Regionals 100 metres Breaststroke 1:54.00 1:48.00 1:39.00 1:31.00 1:29.00 1:27.00 1:25.00 1:23.00 No QT at Regionals 100 metres Backstroke 1:39.00 1:35.00 1:31.00 1:20.00 1:18.00 1:16.00 1:15.00 1:11.00 No QT at Regionals 100 metres Butterflystroke 1:43.00 1:36.00 1:29.00 1:18.00 1:16.00 1:14.00 1:12.00 1:08.00 No QT at Regionals 200 metres Freestyle 2:39.00 2:25.00 2:23.00 2:20.00 2:17.00 2:15.00 No QT at Regionals 200 metres Breaststroke 3:24.00 3:10.00 3:05.00 3:01.00 2:58.00 2:55.00 200 metres Backstroke 3:00.00 2:50.00 2:45.00 2:40.00 2:36.00 2:31.00 200 metres Butterflystroke 3:00.00 2:50.00 2:47.00 2:41.00 2:35.00 2:30.00 200 metres Individual Medley 3:33.00 3:18.00 3:05.00 2:45.00 2:43.00 2:40.00 2:37.00 2:35.00 Paper Nominations 400 metres Freestyle 5:20.00 5:00.00 4:43.00 4:35.00 4:30.00 4:25.00 400 metres Individual Medley 6:28.00 5:50.00 5:42.20 5:22.60 5:22.00 5:20.00 13 – 19 Years 800 metres Freestyle 8:55.00 1500 metres Freestyle 17.45.00 NOTES * All students must be enrolled in an affiliated school, college, special school or school of distance education. -

Sydney Striders Road Runners' Club Australia

SYDNEY STRIDERS ROAD RUNNERS’ CLUB AUSTRALIA EDITION No 106 SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER 2008 Jeremey joins jogging juggernaut eremey Horne is one of the Striders’ recent “blue ribbon” acquisitions. A champion fun runner, Jeremey Jbegan competitive running at the age of 22 and has been moving at a rapid pace ever since. The child of dairy farmers, Jeremey grew up in a small country town, where a lack of distractions led to an early athletic diet of cricket, AFL and tennis. Upon finishing high school, Jeremey moved to Canberra to study Sports Science, at which time he started running to keep fit (and presumably to keep warm in the bitter Canberra winters). After completing his Sports Science degree, Jeremey moved to Sydney to study Physiotherapy. It was at this time that he entered his first race – the Woodstock fun run. At the same time he became involved in Duathlon and went on to represent Australia in the World Championships in Italy in 1996. Unfortunately, the pressure of university studies, part time work and training became too great and Jeremey was forced to abandon this sport. Then, in 1999, Jeremey INSIDE BLISTER 106 started running for Athletics Ferrous fellows focus on far East in the state flung fiery folly in Hawaii winter championships. David Crinit - thoughts are In an impressive debut season, writ - on the negative split In 2003, Jeremey joined Randwick Botany Harriers, for Jeremey was whom he raced for a number of years. Then, in 2008, the named distance Tony Wong on song, not for lure of the Sydney Striders became too overwhelming, runner of the long, in old Hong Kong and Jeremey became a Strider. -

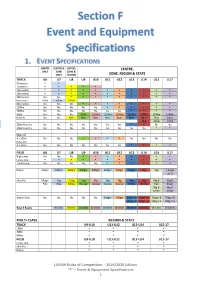

LANSW Event & Specification

Section F Event and Equipment Specifications 1. EVENT SPECIFICATIONS CENTRE CENTRE & CENTRE, CENTRE, ONLY ZONE ZONE & ONLY REGION ZONE, REGION & STATE TRACK U6 U7 U8 U9 U10 U11 U12 U13 U14 U15 U17 50 metres 70 metres 100 metres 200 metres 400 metres No No Pack Start 300m 500m 700m 800 metres No No No 1500m No No No No No 3000m No No No No No No No Walk No No No 700m 1100m 1100m 1500m 1500m 1500m 1500m 1500m Hurdles No No 60m 60m 60m 80m 80m 80m 80 G 90 G 100 G 90 B 100 B 110 B 200m Hurdles No No No No No No No No No 300m Hurdles No No No No No No No No No Relay Jnr 4 x 100m No No No No No No No Relay Snr 4 x 100m No No No No No No No FIELD U6 U7 U8 U9 U10 U11 U12 U13 U14 U15 U17 High Jump No No No Long Jump Triple Jump No No No No No Discus 350gm 350gm 500gm 500gm 500gm 500gm 750gm 750gm 1kg 1kg 1.5kg B 1kg G Shot Put 500gm 1kg 1.5kg 2kg 2kg 2kg 2kg 3kg 3kg 4kg B 5kg B Pink Blue Yellow Orange Orange Orange Orange White White Red Green 3kg G 3kg G White White Javelin Boys No No No No No 400gm 400gm 600gm B 600gm B 700gm B 700gm B 400gm G 400gm G 500gm G 500gm G Total # Events 8 events 9 events 11 events 11 events 13 events 13 events 15 events 15 events 15 events 15 events MULTI-CLASS REGION & STATE TRACK U9-U10 U11-U12 U13-U14 U15-17 100m 200m 800m FIELD U9-U10 U11-U12 U13-U14 U15-17 Long Jump Shot Put Discus LANSW Rules of Competition – 2019/2020 Edition “F” – Event & Equipment Specifications 1 2. -

Track Stats Index

Index to Track Stats Volumes 31-46 (1993-2008) compiled by Keith Morbey & Stuart Mazdon (figures in brackets are page numbers, usually for small mentions which may not be in the contents page) Contents AUTHORS ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 AREAS......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 CHAMPIONSHIPS and MEETINGS............................................................................................................................ 6 EVENTS – Men............................................................................................................................................................ 7 EVENTS – Women......................................................................................................................................................11 MISCELLANEOUS.....................................................................................................................................................12 NATIONS ...................................................................................................................................................................12 PEOPLE ......................................................................................................................................................................14 RECORDS...................................................................................................................................................................18 -

State Records – April 2013

STATE RECORDS as at April 2013 (E) = Electronic Record UNDER 7 GIRLS Event Name Centre Performance Date 50 Metres Annette Cavanagh Blacktown 8.0 24-Mar-79 Andrea Parker Hills District 8.0 24-Mar-79 50 Metres (E) Alannah Martin Doonside 9.01 4-Mar-12 70 Metres Karolyn Cassidy Hills District 10.8 11-Mar-78 Jo-anne Swan Camden 10.8 16-Mar-80 100 Metres Belinda Ruiz Lake Illawarra 15.9 7-Mar-82 100 Metres (E) Montana Monk Wallsend RSL 17.50 6-Mar-11 200 Metres Jo-anne Swan Camden 33.1 15-Mar-80 Long Jump Sally Eggleton Ku-Ring-Gai 3.60m 21-Feb-82 Belinda Jones Hornsby 3.60m 21-Feb-82 Shot Put (1kg) Kylie Standing Bankstown 8.01m 20-Mar-83 Discus (350gm) Mallory Bassett Hornsby 21.24m 3-Mar-07 UNDER 7 BOYS Event Name Centre Performance Date 50 Metres Scott Weaver Scully Park 7.4 12-Mar-77 50 Metres (E) James Apostolakis Illawong 8.96 6-Mar-11 Lachlan Herbert Ku-Ring-Gai 8.96 3-Mar-13 70 Metres Graham Garnett Hornsby 10.8 18-Mar-73 Jonathon Weaver Scully Park 10.8 11-Mar-78 Adam Davis Greystanes 10.8 25-Mar-79 Jeffrey Poulter Bankstown 10.8 16-Mar-80 100 Metres Alan Powderly Walcha 15.4 7-Mar-82 100 Metres (E) James Apostolakis Illawong 17.30 6-Mar-11 Kalani Vella Albion Park 17.30 3-Mar-13 200 Metres Enzo Granata Holroyd 32.6 19-Mar-83 Long Jump Mark Lever Hornsby 3.71m 5-Feb-77 Greg Hammond Hornsby 3.71m 21-Mar-81 Shot Put (1kg) Blake Toohey Sutherland 10.20m 7-Mar-10 Discus (350gm) Anthony Krkovski Port Hacking 23.09m 5-Mar-05 UNDER 8 GIRLS Event Name Centre Performance Date 70 Metres Annette Cavanagh Blacktown 10.3 16-Mar-80 70 Metres (E)