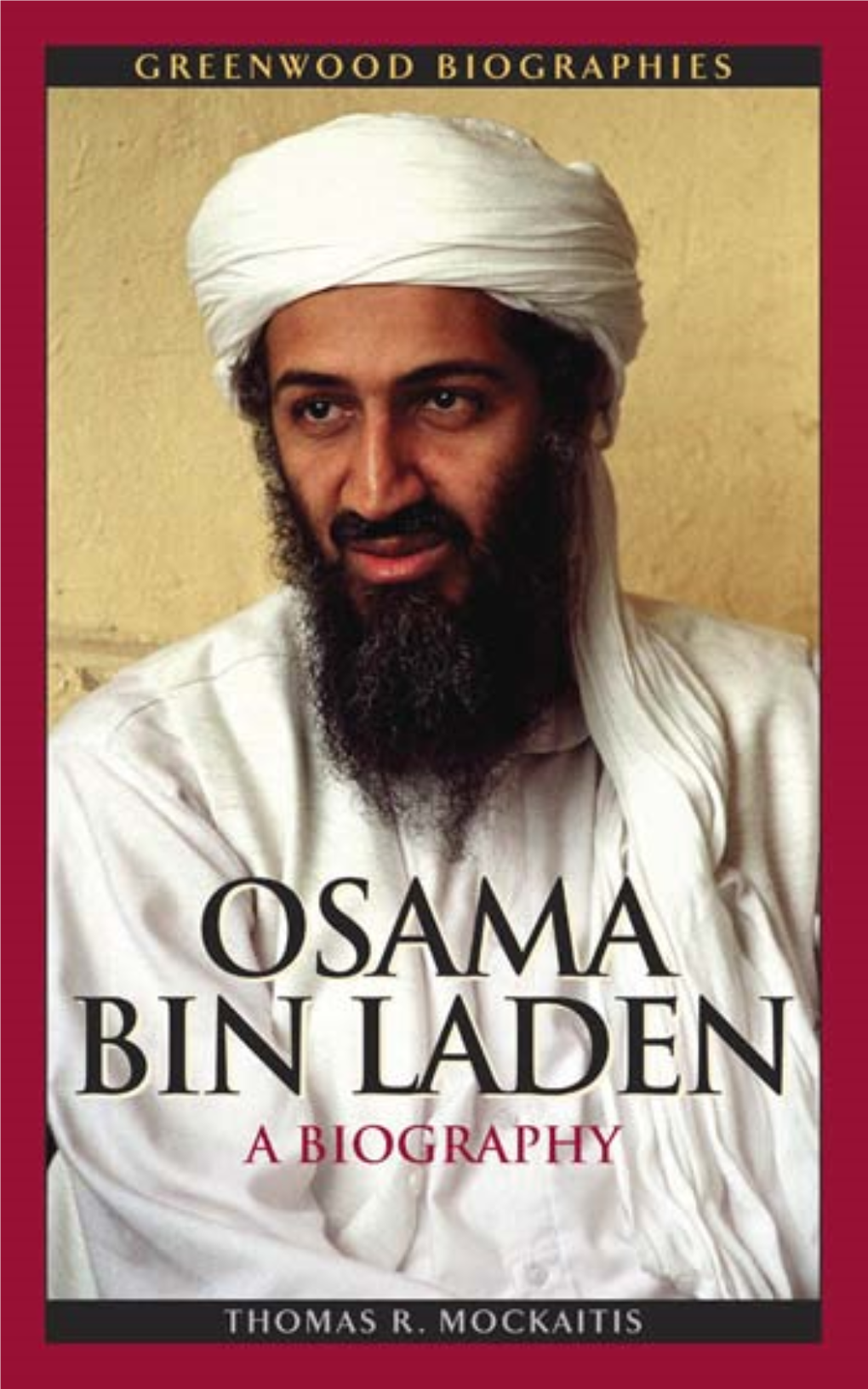

Osama Bin Laden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Bibliography (From Sheikhs to Sultanism)

FULL BIBLIOGRAPHY (FROM SHEIKHS TO SULTANISM) Academic sources (books, chapters, and journal articles) P. Aarts and C. Roelants, Saudi Arabia: A Kingdom in Peril (London: Hurst & Co., 2015) A. Abdulla, The Gulf Moment in Contemporary Arab History (Beirut: Dar Al-Farabi, 2018) [in Arabic] I. Abed and P. Hellyer (eds.), United Arab Emirates: A New Perspective (Dubai: Trident, 2001) P. Abel and S. Horák, ‘A tale of two presidents: personality cult and symbolic nation-building in Turkmenistan’ in Nationalities Papers, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2015 A. Abrahams and A. Leber, ‘Framing a murder: Twitter influencers and the Jamal Khashoggi incident' in Mediterranean Politics [April 2020 online first view] D. Acemoglu, T. Verdier, and J. Robinson, ‘Kleptocracy and Divide-and-Rule: A Model of Personal Rule’ in Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 2, Nos. 2-3, 2004 G. Achcar, The People Want: A Radical Exploration of the Arab Uprising (London: Saqi, 2013) A. Adib-Moghaddam (ed.), A Critical Introduction to Khomeini (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014) I. Ahyat, ‘Politics and Economy of Banjarmasin Sultanate in the Period of Expansion of the Netherlands East Indies Government in Indonesia, 1826-1860’ in Tawarikh: International Journal for Historical Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2012 A. Al-Affendi, ‘A Trans-Islamic Revolution?’, Critical Muslim, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2012 M. Al-Atawneh, ‘Is Saudi Arabia a Theocracy? Religion and Governance in Contemporary Saudi Arabia’ in Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 45, No. 5, 2009 H. Albrecht and O. Schlumberger, ‘Waiting for Godot: Regime Change Without Democratization in the Middle East’ in International Political Science Review, Vol. -

Volume XV, Issue 1 February 2021 PERSPECTIVES on TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 1

ISSN 2334-3745 Volume XV, Issue 1 February 2021 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 1 Table of Content Welcome from the Editors...............................................................................................................................1 Articles Bringing Religiosity Back In: Critical Reflection on the Explanation of Western Homegrown Religious Terrorism (Part I)............................................................................................................................................2 by Lorne L. Dawson Dying to Live: The “Love to Death” Narrative Driving the Taliban’s Suicide Bombings............................17 by Atal Ahmadzai The Use of Bay’ah by the Main Salafi-Jihadist Groups..................................................................................39 by Carlos Igualada and Javier Yagüe Counter-Terrorism in the Philippines: Review of Key Issues.......................................................................49 by Ronald U. Mendoza, Rommel Jude G. Ong and Dion Lorenz L. Romano Variations on a Theme? Comparing 4chan, 8kun, and other chans’ Far-right “/pol” Boards....................65 by Stephane J. Baele, Lewys Brace, and Travis G. Coan Research Notes Climate Change—Terrorism Nexus? A Preliminary Review/Analysis of the Literature...................................81 by Jeremiah O. Asaka Inventory of 200+ Institutions and Centres in the Field of Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism Research.....93 by Reinier Bergema and Olivia Kearney Resources Counterterrorism Bookshelf: Eight Books -

March 2020 MLM

VOLUME XI, ISSUE 3, MARCH 2020 THE JAMESTOWN FOUNDATION The Past as Escape from The GNA’s Latest Defection: A Precedent: Is Pakistan: TTP Profile of the AQAP’s New the Taliban’s Spokesperson Tripoli Emir: Who is Military Chief Militiaman- Ehsan ullah Khalid Batarfi? Sirajuddin Turned-Diplomat BRIEF Ehsan Fled Mohamed Shaeban Haqqani Ready from Custody ‘al-Mirdas’ for Peace? LUDOVICO SUDHA JOHN FOULKES FARHAN ZAHID DARIO CRISTIANI CARLINO RAMACHANDRAN VOLUME XI, ISSUE 3 | MARCH 2020 Bashir Qorgab—al-Shabaab Veteran al-Shabaab (Radio Muqdisho, March 7; Commander Killed in U.S. Airstrike Jerusalem Post, March 8). John Foulkes Qorgab was born sometime between 1979 and 1982, and was a senior al-Shabaab leader for On February 22, an airstrike carried out by U.S. over a decade, having been one of ten members Africa Command killed a senior al-Shabaab of al-Shabaab’s executive council, as of 2008. leader, Bashir Mohamed Mahamoud (a.k.a. On April 13, 2010, the United States placed Bashir Qorgab) (Radio Muqdisho, March 7). As Qorgab on the list of specially designated global a senior operational commander in the Somali terrorists. The U.S. State Department’s Reward militant group, Qorgab is believed to have been for Justice program offered $5 million for involved in the planning of the attack on the information that led to his arrest in June 2012, military base Camp Simba and its Manda Bay pointing to the fact that he led a mortar attack airstrip used by U.S. and Kenyan forces. The against the then-Transitional Federal attack killed one U.S. -

Summary of Information on Jihadist Websites the First Half of August 2015

ICT Jihadi Monitoring Group PERIODIC REVIEW Bimonthly Report Summary of Information on Jihadist Websites The First Half of August 2015 International Institute for Counter Terrorism (ICT) Additional resources are available on the ICT Website: www.ict.org.il This report summarizes notable events discussed on jihadist Web forums during the first half of August 2015. Following are the main points covered in the report: Following a one-year absence, Sheikh Ayman al-Zawahiri re-emerges in the media in order to give a eulogy in memory of Mullah Omar, the leader of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, and to swear allegiance to its new leader, Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansoor. Al-Zawahiri vows to work to apply shari’a and continue to wage jihad until the release of all Muslim occupied lands. In addition, he emphasized that the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is the only legitimate emirate. The next day, Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansoor announces that he accepted al- Zawahiri’s oath of allegiance. In addition, various Al-Qaeda branches and jihadist organizations that support Al-Qaeda gave eulogies in memory of Mullah Omar. Hamza bin Laden, the son of former Al-Qaeda leader, Osama bin Laden, renews his oath of allegiance to the leader of the Taliban in Afghanistan, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and praises the leaders of Al-Qaeda branches for fulfilling the commandment to wage jihad against the enemies of Islam. In reference to the arena of jihad in Syria, he recommends avoiding internal struggles among the mujahideen in Syria and he calls for the liberation of Al-Aqsa Mosque from the Jews. -

The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: an Empirical Study

© Reuters/HO Old – Detainees at XRay Camp in Guantanamo. The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study Benjamin Wittes and Zaahira Wyne with Erin Miller, Julia Pilcer, and Georgina Druce December 16, 2008 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Public Record about Guantánamo 4 Demographic Overview 6 Government Allegations 9 Detainee Statements 13 Conclusion 22 Note on Sources and Methods 23 About the Authors 28 Endnotes 29 Appendix I: Detainees at Guantánamo 46 Appendix II: Detainees Not at Guantánamo 66 Appendix III: Sample Habeas Records 89 Sample 1 90 Sample 2 93 Sample 3 96 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he following report represents an effort both to document and to describe in as much detail as the public record will permit the current detainee population in American T military custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Since the military brought the first detainees to Guantánamo in January 2002, the Pentagon has consistently refused to comprehensively identify those it holds. While it has, at various times, released information about individuals who have been detained at Guantánamo, it has always maintained ambiguity about the population of the facility at any given moment, declining even to specify precisely the number of detainees held at the base. We have sought to identify the detainee population using a variety of records, mostly from habeas corpus litigation, and we have sorted the current population into subgroups using both the government’s allegations against detainees and detainee statements about their own affiliations and conduct. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

Case: 11-3490 Document: 145 Page: 1 04/16/2013 908530 32 11-3294-cv(L), et al. In re Terrorist Attacks on September 11, 2001 (Asat Trust Reg., et al.) UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT August Term, 2012 (Argued On: December 4, 2012 Decided: April 16, 2013) Docket Nos. 11-3294-cv(L), 11-3407-cv, 11-3490-cv, 11-3494-cv, 11-3495-cv, 11-3496-cv, 11-3500-cv, 11-3501- cv, 11-3502-cv, 11-3503-cv, 11-3505-cv, 11-3506-cv, 11-3507-cv, 11-3508-cv, 11-3509-cv, 11-3510- cv, 11-3511-cv, 12-949-cv, 12-1457-cv, 12-1458-cv, 12-1459-cv. _______________________________________________________________ IN RE TERRORIST ATTACKS ON SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 (ASAT TRUST REG., et al.) JOHN PATRICK O’NEILL, JR., et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. ASAT TRUST REG., AL SHAMAL ISLAMIC BANK, also known as SHAMEL BANK also known as BANK EL SHAMAR, SCHREIBER & ZINDEL, FRANK ZINDEL, ENGELBERT SCHREIBER, SR., ENGELBERT SCHREIBER, JR., MARTIN WATCHER, ERWIN WATCHER, SERCOR TREUHAND ANSTALT, YASSIN ABDULLAH AL KADI, KHALED BIN MAHFOUZ, NATIONAL COMMERCIAL BANK, FAISAL ISLAMIC BANK, SULAIMAN AL-ALI, AQEEL AL-AQEEL, SOLIMAN H.S. AL-BUTHE, ABDULLAH BIN LADEN, ABDULRAHMAN BIN MAHFOUZ, SULAIMAN BIN ABDUL AZIZ AL RAJHI, SALEH ABDUL AZIZ AL RAJHI, ABDULLAH SALAIMAN AL RAJHI, ABDULLAH OMAR NASEEF, TADAMON ISLAMIC BANK, ABDULLAH MUHSEN AL TURKI, ADNAN BASHA, MOHAMAD JAMAL KHALIFA, BAKR M. BIN LADEN, TAREK M. BIN LADEN, OMAR M. BIN LADEN, DALLAH AVCO TRANS ARABIA CO. LTD., DMI ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICES S.A., ABDULLAH BIN SALEH AL OBAID, ABDUL RAHMAN AL SWAILEM, SALEH AL-HUSSAYEN, YESLAM M. -

Perfect Enemy the Law Enforcement Manual of Islamist Terrorism

Perfect Enemy ABOUT THE AUTHOR Captain Dean T. Olson formerly commanded the Criminal Investiga- tion Bureau of the Douglas County Sheriff’s Department in Omaha, NE, including the department’s participation in the regional Joint Terrorism Task Force. He retired in 2008 after 30 years of law enforcement service. He earned a BS in Criminal Justice and a Masters Degree in Public Ad- ministration from the University of Nebraska at Omaha. He also earned a Master of Arts Degree in National Security Affairs, Homeland Defense and Security from the Naval Postgraduate School, Center for Home- land Defense and Security, in Monterey, CA. He is a graduate of the 193rd Session of the FBI National Academy and is adjunct professor of Criminal Justice for several Midwestern universities. He has traveled extensively in the Middle East and Muslim lands. His areas of expertise include terrorism financing, risk management in suicide/homicide ter- rorism prevention, agroterrorism, threat assessment of domestic radical groups at risk of escalation to terrorism and Islamist terrorism. Perfect Enemy The Law Enforcement Manual of Islamist Terrorism By Captain Dean T. Olson, MPA, MA CHARLESC THOMAS • PUBLISHER, LTD. Springfield • Illinois • U.S.A. Published and Distributed Throughout the World by CHARLES C THOMAS • PUBLISHER, LTD. 2600 South First Street Springfield, Illinois 62704 This book is protected by copyright. No part of it may be reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher. All rights reserved. © 2009 by CHARLES C THOMAS • PUBLISHER, LTD. ISBN 978-0-398-07885-0 (hard) ISBN 978-0-398-07886-7 (paper) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2009012250 With THOMAS BOOKS careful attention is given to all details of manufacturing and design. -

Islamic Relief Charity / Extremism / Terror

Islamic Relief Charity / Extremism / Terror meforum.org Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 From Birmingham to Cairo �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Origins ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Branches and Officials ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Government Support ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 17 Terror Finance ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 20 Hate Speech ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 25 Charity, Extremism & Terror ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 29 What Now? �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 32 Executive Summary What is Islamic Relief? Islamic Relief is one of the largest Islamic charities in the world. Founded in 1984, Islamic Relief today maintains -

Al Qaeda 2020 Website.Indd

AL QAEDA Quick Facts Geographical Areas of Operation: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, North Africa, and Somalia Numerical Strength (Members): Exact numbers unknown Leadership: Ayman al-Zawahiri Religious Identification:Sunni Islam Quick Facts State Department’s Country Reports on Terrorism (2019) INTRODUCTION Born out of the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan during the Cold War, Al Qaeda would grow over the ensuing decades to become one of the most prolific and consequential global terror groups to ever exist. Its mission – to form a global movement of Islamic sharia governance rooted in Wahhabi and Ikhwani religious philosophies and to wage war against the United States and its allies – has taken the cellular organization to South and Central Asia, North and Sub-Saharan Africa, North America, the South Pacific, and Europe. The organization has killed thousands of people, and instigated a now-decades old war with the events of September 11, 2001. In contrast to its ideological progeny and current rival, the Islamic State (IS), Al Qaeda tries to blend in with the societies it eventually seeks to politically co-opt. This has led to the formation of several satellite organizations, each of which operate at various capacities and different capabilities. After a period of relative inactivity on the global jihad stage, Al Qaeda is now seemingly reemerging. The 2020 assassination of U.S. Navy servicemembers in Pensacola, Florida, the fall of the Islamic State’s physical caliphate, and continued activity in both Afghanistan and North Africa all signal the group’s continued viability, as well as its ongoing desire to reclaim the mantle of the world’s preeminent Islamist extremist organization. -

Securitization Theory and the Canadian Construction of Omar Khadr

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018-05-18 Securitization Theory and the Canadian Construction of Omar Khadr Pirnie, Elizabeth Irene Pirnie, E. I. (2018). Securitization Theory and the Canadian Construction of Omar Khadr (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/31940 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/106673 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Securitization Theory and the Canadian Construction of Omar Khadr by Elizabeth Irene Pirnie A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA May, 2018 © Elizabeth Irene Pirnie 2018 ii Abstract While the provision of security and protection to its citizens is one way in which sovereign states have historically claimed legitimacy (Nyers, 2004: 204), critical security analysts point to security at the level of the individual and how governance of a nation’s security underscores the state’s inherently paradoxical relationship to its citizens. Just as the state may signify the legal and institutional structures that delimit a certain territory and provide and enforce the obligations and prerogatives of citizenship, the state can equally serve to expel and suspend modes of legal protection and obligation for some (Butler and Spivak, 2007). -

Federal Court of Canada

Federal Court Cour fédérale Date: 20100705 Docket: T-230-10 Citation: 2010 FC 715 Ottawa, Ontario, July 5, 2010 PRESENT: The Honourable Mr. Justice Zinn BETWEEN: OMAR AHMED KHADR Applicant and THE PRIME MINISTER OF CANADA, THE MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS and THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE Respondents AND BETWEEN: Docket: T-231-10 OMAR AHMED KHADR Applicant and THE PRIME MINISTER OF CANADA and THE MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Respondents REASONS FOR JUDGMENT AND JUDGMENT [1] These applications, at their heart, ask whether Mr. Khadr was entitled to procedural fairness by the executive in making its decision as to how Canada would respond to the declaration issued Page: 2 by the Supreme Court of Canada in Canada (Prime Minister) v. Khadr , 2010 SCC 3 [ Khadr II ]. In Khadr II , the Court held that Mr. Khadr’s rights under section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms had been breached by Canada, and issued a declaration to provide the legal framework for Canada to take steps to remedy that breach. For the reasons that follow, in the unique circumstances of this case, I find that Omar Khadr was entitled to procedural fairness by the executive when making its decision as to the appropriate remedy to take. I further find that the executive failed to provide Mr. Khadr with the level of fairness that was required when making its decision. Both the degree of fairness to which he was entitled and the remedy for having failed to provide it are unique and challenging issues. Background [2] The facts surrounding Mr. -

The United States V. Omar Khadr Pre-Trial Observation Report October 22, 2008

The United States v. Omar Khadr Pre-Trial Observation Report October 22, 2008 International Human Rights Program Faculty of Law, University of Toronto The United States v. Omar Khadr Pre-Trial Observation Report October 22, 2008 Report authors: Tony Navaneelan and Kate Oja, J.D. Candidates ‘09 Prepared for the International Human Rights Program Faculty of Law, University of Toronto 39 Queen’s Park Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2C3 Telephone (416) 946 8730 Fax (416) 978 8894 1 About the International Human Rights Program: The International Human Rights Program (IHRP) of the University of Toronto, Faculty of Law is dedicated to promoting global human rights through legal education, research and advocacy. The mission of the International Human Rights Program is to mobilize lawyers to address international human rights issues and to develop the capacity of students and program participants to establish human rights norms in domestic and international contexts. Cover photograph: Military barracks at ‘Camp Justice,’ Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (Courtesy of T. Navaneelan) 2 CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 4 II. FACTUAL BACKGROUND 4 III. LEGAL PROCEEDINGS AGAINST OMAR KHADR 10 IV. THE MILITARY COMMISSIONS ACT 15 V. U.S. v. OMAR KHADR: OCTOBER 22 PRE-TRIAL HEARING 20 Motion 1: Appropriate Relief: Access to Intelligence Interrogations 21 Motion 2: Elements of the offence 25 Motion 3: Motion for continuance 30 VI. RECOMMENDATIONS 35 3 I. Introduction Omar Ahmed Khadr is a young Canadian and the only remaining citizen of a Western country held in US custody in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Omar is currently facing charges for offences under the Military Commissions Act 2006 for acts that allegedly occurred in Afghanistan in 2002, when he was fifteen years old.1 On 22 October 2008, what was intended to be Omar’s final pre-trial hearing before his November 10 trial date was held in Guantánamo Bay before Military Judge Patrick Parrish.