Summary and Conclusion Chapter Review Questions Key Terms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ernest Sosa and Virtuously Begging the Question

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 9 May 18th, 9:00 AM - May 21st, 5:00 PM Ernest Sosa and virtuously begging the question Michael Walschots University of Windsor Scott F. Aikin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Walschots, Michael and Aikin, Scott F., "Ernest Sosa and virtuously begging the question" (2011). OSSA Conference Archive. 38. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA9/papersandcommentaries/38 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ernest Sosa and virtuously begging the question MICHAEL WALSCHOTS Department of Philosophy University of Windsor 401 Sunset Ave. Windsor, ON N9P 3B4 Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper discusses the notion of epistemic circularity, supposedly different from logical circu- larity, and evaluates Ernest Sosa’s claim that this specific kind of circular reasoning is virtuous rather than vicious. I attempt to determine whether or not the conditions said to make epistemic circularity a permissible instance of begging the question could make other instances of circular reasoning equally permissible. KEYWORDS: begging the question, circular reasoning, Ernest Sosa, epistemic circularity, petitio principii, reliabilism. 1. INTRODUCTION In 1986, William Alston introduced the idea of ‘epistemic circularity’, which involves assuming the reliability of a given source of belief during the process of proving the reli- ability of that same source. -

Religious Worldviews*

RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEWS* SECULAR POLITICAL CHRISTIANITY ISLAM MARXISM HUMANISM CORRECTNESS Nietzsche/Rorty Sources Koran, Hadith Humanist Manifestos Marx/Engels/Lenin/Mao/ The Bible Foucault/Derrida, Frankfurt Sunnah I/II/ III Frankfurt School Subjects School Theism Theism Atheism Atheism Atheism THEOLOGY (Trinitarian) (Unitarian) PHILOSOPHY Correspondence/ Pragmatism/ Pluralism/ Faith/Reason Dialectical Materialism (truth) Faith/Reason Scientism Anti-Rationalism Moral Relativism Moral Absolutes Moral Absolutes Moral Relativism Proletariat Morality (foster victimhood & ETHICS (Individualism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) /Collectivism) Creationism Creationism Naturalism Naturalism Naturalism (Intelligence, Time, Matter, (Intelligence, Time Matter, ORIGIN SCIENCE (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) Energy) Energy) 1 Mind/Body Dualism Monism/self-actualization Socially constructed self Monism/behaviorism Mind/Body Dualism (fallen) PSYCHOLOGY (non fallen) (tabula rasa) Monism (tabula rasa) (tabula rasa) Traditional Family/Church/ Polygamy/Mosque & Nontraditional Family/statist Destroy Family, church and Classless Society/ SOCIOLOGY State State utopia Constitution Anti-patriarchy utopia Critical legal studies Proletariat law Divine/natural law Shari’a Positive law LAW (Positive law) (Positive law) Justice, freedom, order Global Islamic Theocracy Global Statism Atomization and/or Global & POLITICS Sovereign Spheres Ummah Progressivism Anarchy/social democracy Stateless Interventionism & Dirigisme Stewardship -

The Philosophical Underpinnings of Educational Research

The Philosophical Underpinnings of Educational Research Lindsay Mack Abstract This article traces the underlying theoretical framework of educational research. It outlines the definitions of epistemology, ontology and paradigm and the origins, main tenets, and key thinkers of the 3 paradigms; positivist, interpetivist and critical. By closely analyzing each paradigm, the literature review focuses on the ontological and epistemological assumptions of each paradigm. Finally the author analyzes not only the paradigm’s weakness but also the author’s own construct of reality and knowledge which align with the critical paradigm. Key terms: Paradigm, Ontology, Epistemology, Positivism, Interpretivism The English Language Teaching (ELT) field has moved from an ad hoc field with amateurish research to a much more serious enterprise of professionalism. More teachers are conducting research to not only inform their teaching in the classroom but also to bridge the gap between the external researcher dictating policy and the teacher negotiating that policy with the practical demands of their classroom. I was a layperson, not an educational researcher. Determined to emancipate myself from my layperson identity, I began to analyze the different philosophical underpinnings of each paradigm, reading about the great thinkers’ theories and the evolution of social science research. Through this process I began to examine how I view the world, thus realizing my own construction of knowledge and social reality, which is actually quite loose and chaotic. Most importantly, I realized that I identify most with the critical paradigm assumptions and that my future desired role as an educational researcher is to affect change and challenge dominant social and political discourses in ELT. -

Introduction to Philosophy. Social Studies--Language Arts: 6414.16. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 086 604 SO 006 822 AUTHOR Norris, Jack A., Jr. TITLE Introduction to Philosophy. Social Studies--Language Arts: 6414.16. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 20p.; Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; Grade 10; Grade 11; Grade 12; *Language Arts; Learnin4 Activities; *Logic; Non Western Civilization; *Philosophy; Resource Guides; Secondary Grades; *Social Studies; *Social Studies Units; Western Civilization IDENTIFIERS *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT Western and non - western philosophers and their ideas are introduced to 10th through 12th grade students in this general social studies Quinmester course designed to be used as a preparation for in-depth study of the various schools of philosophical thought. By acquainting students with the questions and categories of philosophy, a point of departure for further study is developed. Through suggested learning activities the meaning of philosopky is defined. The Socratic, deductive, inductive, intuitive and eclectic approaches to philosophical thought are examined, as are three general areas of philosophy, metaphysics, epistemology,and axiology. Logical reasoning is applied to major philosophical questions. This course is arranged, as are other quinmester courses, with sections on broad goals, course content, activities, and materials. A related document is ED 071 937.(KSM) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY U S DEPARTMENT EDUCATION OF HEALTH. NAT10N41 -

Waldomiro José Silva Filho1 Marcos Antonio Alves2

Presentation Editorial / Editorial PRESENTATION Waldomiro José Silva Filho 1 Marcos Antonio Alves 2 It is with great happiness and honor that we present this special issue of Trans/Form/Ação: Unesp journal of philosophy in honor of Ernest Sosa. One of the most influential voices in the contemporary philosophy, Ernest Sosa was born in Cárdenas, Cuba, on June 17, 1940. He earned his Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) and Master of Arts (M.A.) from the University of Miami and his Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) from the University of Pittsburgh in 1964. Since 2007, he has been Board of Governors Professor of Philosophy at Rutgers University. There is no doubt that Sosa is responsible for one of the revolution in Epistemology that will mark the history of philosophy. However, he also opened new paths in several central issues of philosophy, such as Metaphysics, Philosophy of Language and Philosophy of Mind. In 2020, the world philosophical community on all continents joined with his close friends and family to celebrate Ernie’s 80th birthday. Dozens of publications, books, journals, and webinars were held, even amidst the humanitarian devastation of the pandemic. The journal Trans/Form/Ação 1 Full Professor at the Philosophy Department of Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), Salvador, BA – Brazil. Researcher of the CNPq, Brazil. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0874-9599 E-mail: [email protected] 2 Editor da Trans/Form/Ação: Unesp journal of Philosophy. Professor at the Philosophy Department of and Coordinator of Post Graduation Program in Philosophy – São Paulo State University (UNESP), Marília, SP – Brazil. -

Dilemmas of Objectivity

SOCIALEPISTEMOLOGY , 2002, VOL. 16, NO . 3, 267–281 Dilemmas of objectivity MARIANNE JANACK Objectivityis a virtuein most circles.As weevaluateour students (even those we don’t like)we tryto be objective. As wedeliberateon juries,we tryto be objective about the accused and thevictim, the prosecutor and thedefence. As wetoteup theevidence for and againsta certainposition or theory, we try to separate our personal preferences fromthe argument, or we try to separate the arguer (and ourevaluation of him/ her) fromthe case presented.Sometimes we do wellat this,sometimes we do lesswell at it,but we recognize something valuable intheeffort. Considerthe following cases inwhich objectivity or its failure is at issue: (1)A professorgives his favourite student an Ainaclass inwhichthe student has done onlymediocre work. (2)A scientistoverlooks evidence that would call intoquestion a theorythat she has goneout on alimbto defend,and has investedmuch timeand energyin pursuing. (3)A scientistskews data inorder to bolster support for a favouritepolitical cause. (4)A particularphilosophy journal, which does not use a blindreview process, only publishesarticles written by men. (5)A memberof a trialjury questions evidence presented in atrialbecause it conicts withracist stereotypes. Some ofthese invocations of objectivity imply that a separationshould exist between thesource or origin of the theory or argument and theargument itself. Some imply thatour deliberations should be answerable only to ‘ theevidence’ or ‘ thefacts’ and notsimply to our own preferences and idiosyncrasies.Some implythat our emotionsor biases (broadly understood to include emotions) should not interfere withour reasoning. Inits ontological guise, the appeal toobjectivity is a wayof appealing to the way thingsare, or to the world as itis independently of our desires about howwe want it tobe. -

Thomas Kelly

Thomas Kelly Department of Philosophy [email protected] Princeton University https://www.princeton.edu/~tkelly/ 212 1879 Hall (617)308-9673 Princeton, NJ 08544 Employment Princeton University, 2004- Professor of Philosophy, 2012- Associated Faculty, University Center for Human Values, 2006- Associate Professor of Philosophy, 2007-2012 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, 2004-2007 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, University of Notre Dame, 2003-2004. Junior Fellow, Harvard Society of Fellows, 2000-2003. Education Ph.D. in Philosophy, Harvard University, 2001. Dissertation: Rationality and the Ethics of Belief Committee: Robert Nozick, Derek Parfit, James Pryor. B.A. in Philosophy, summa cum laude, University of Notre Dame, 1994. Areas of Specialization Epistemology, Rationality, Philosophical Methodology. Areas of Competence History of Analytic Philosophy, Philosophy of Science, Political Philosophy, Ethics, Philosophy of Religion. 2 Publications Papers (32) “Bias: Some Conceptual Geography.” To appear in Nathan Ballantyne and David Dunning (eds.) Reason, Bias, and Inquiry: New Perspectives from the Crossroads of Epistemology and Psychology. (31) “Evidence.” To appear in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (30) “Are There Any Successful Philosophical Arguments?” (co-authored with Sarah McGrath). In John Keller (ed.) Being, Freedom, and Method: Themes from the Philosophy of Peter van Inwagen (Oxford University Press 2017): 324-339. With a reply by Peter van Inwagen. (29) “Religious Diversity and the Epistemology of Theology” (co-authored with Nathan King). In William Abraham and Fred Aquino (eds.) The Oxford Handbook to the Epistemology of Theology (Oxford University Press 2017): 309-324. (28) “Historical versus Current Time Slice Theories in Epistemology.” In Hilary Kornblith and Brian McLaughlin (eds.) Goldman and His Critics (Blackwell Publishers 2016): 43-65. -

Introduction to Philosophy

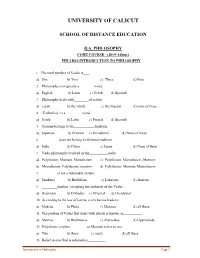

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION B.A. PHILOSOPHY CORE COURSE - (2019-Admn.) PHL1 B01-INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY 1. The total number of Vedas is . a) One b) Two c) Three d) Four 2. Philosophy is originally a word. a) English b) Latin c) Greek d) Spanish 3. Philosophy deals with of reality. a) a part b) the whole c) the illusion d) none of these 4. ‘Esthetikos’ is a word. a) Greek b) Latin c) French d) Spanish 5. Taoism belongs to the tradition. a) Japanese b) Oriental c) Occidental d) None of these 6. does not belong to Oriental tradition. a) India b) China c) Japan d) None of these 7. Vedic philosophy evolved in the order. a) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism c) Polytheism, Monotheism, Monism b) Monotheism, Polytheism, monism d) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism 8. is not a heterodox system. a) Samkhya b) Buddhism c) Lokayata d) Jainism 9. implies ‘accepting the authority of the Vedas’. a) Heterodox b) Orthodox c) Oriental d) Occidental 10. According to the law of karma, every karma leads to . a) Moksha b) Phala c) Dharma d) all these 11. The portion of Vedas that deals with rituals is known as . a) Mantras b) Brahmanas c) Aranyakas d) Upanishads 12. Polytheism implies as Monism refers to one. a) Two b) three c) many d) all these 13. Belief in one God is referred as . Introduction to Philosophy Page 1 a) Henotheism b) Monotheism c) Monism d) Polytheism 14. Samkhya propounded . a) Dualism b) Monism c) Monotheism d) Polytheism 15. is an Oriental system. -

Legal Theory Workshop UCLA School of Law Samuele Chilovi

Legal Theory Workshop UCLA School of Law Samuele Chilovi Postdoctoral Fellow Pompeu Fabra University “GROUNDING, EXPLANATION, AND LEGAL POSITIVISM” Thursday, October 15, 2020, 12:15-1:15 pm Via Zoom Draft, October 6, 2020. For UCLA Workshop. Please Don’t Cite Or Quote Without Permission. Grounding, Explanation, and Legal Positivism Samuele Chilovi & George Pavlakos 1. Introduction On recent prominent accounts, legal positivism and physicalism about the mind are viewed as making parallel claims about the metaphysical determinants or grounds of legal and mental facts respectively.1 On a first approximation, while physicalists claim that facts about consciousness, and mental phenomena more generally, are fully grounded in physical facts, positivists similarly maintain that facts about the content of the law (in a legal system, at a time) are fully grounded in descriptive social facts.2 Explanatory gap arguments have long played a central role in evaluating physicalist theories in the philosophy of mind, and as such have been widely discussed in the literature.3 Arguments of this kind typically move from a claim that an epistemic gap between physical and phenomenal facts implies a corresponding metaphysical gap, together with the claim that there is an epistemic gap between facts of these kinds, to the negation of physicalism. Such is the structure of, for instance, Chalmers’ (1996) conceivability argument, Levine’s (1983) intelligibility argument, and Jackson’s (1986) knowledge argument. Though less prominently than in the philosophy of mind, explanatory gap arguments have also played some role in legal philosophy. In this area, the most incisive and compelling use of an argument of this kind is constituted by Greenberg’s (2004, 2006a, 2006b) powerful attack on positivism. -

Field Epistemology Metaphysics

To appear in Philosophical Studies, 2009. Online publication January 2009, available on springerlink.com: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9338-1. Epistemology without Metaphysics Hartry Field A common picture of justification among epistemologists is that typically when a person is looking at something red, her sense impressions pump in a certain amount of justification for the belief that there is something red in front of her; but that there can be contrary considerations (e.g. testimony by others that there is nothing red there, at least when backed by evidence that the testimony is reliable) that may pump some of this justification out. In addition, the justification provided by the senses can be fully or partially undercut, say by evidence that the lighting may be bad: this involves creating a leak (perhaps only a small one) in the pipe from sense impressions to belief, so that not all of the justification gets through. On this picture, the job of the epistemologist is to come up with an epistemological dipstick that will measure what overall level of justification we end up with in any given situation. (Presumably the “fluid” to be measured is immaterial, so it takes advanced training in recent epistemological techniques to come up with an accurate dipstick.) Of course there are plenty of variations in the details of this picture. For instance, it may be debated what exactly are the sources of the justificatory fluid. (Does testimony unaided by evidence of its reliability produce justification? Do “logical intuitions” produce it? And so on.) Indeed, coherentists claim that the idea of sources has to be broadened: build a complex enough array of pipes and the fluid will automatically appear to fill them. -

Curriculum Vitae of Alvin Plantinga

CURRICULUM VITAE OF ALVIN PLANTINGA A. Education Calvin College A.B. 1954 University of Michigan M.A. 1955 Yale University Ph.D. 1958 B. Academic Honors and Awards Fellowships Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, 1968-69 Guggenheim Fellow, June 1 - December 31, 1971, April 4 - August 31, 1972 Fellow, American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 1975 - Fellow, Calvin Center for Christian Scholarship, 1979-1980 Visiting Fellow, Balliol College, Oxford 1975-76 National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowships, 1975-76, 1987, 1995-6 Fellowship, American Council of Learned Societies, 1980-81 Fellow, Frisian Academy, 1999 Gifford Lecturer, 1987, 2005 Honorary Degrees Glasgow University, l982 Calvin College (Distinguished Alumni Award), 1986 North Park College, 1994 Free University of Amsterdam, 1995 Brigham Young University, 1996 University of the West in Timisoara (Timisoara, Romania), 1998 Valparaiso University, 1999 2 Offices Vice-President, American Philosophical Association, Central Division, 1980-81 President, American Philosophical Association, Central Division, 1981-82 President, Society of Christian Philosophers, l983-86 Summer Institutes and Seminars Staff Member, Council for Philosophical Studies Summer Institute in Metaphysics, 1968 Staff member and director, Council for Philosophical Studies Summer Institute in Philosophy of Religion, 1973 Director, National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Seminar, 1974, 1975, 1978 Staff member and co-director (with William P. Alston) NEH Summer Institute in Philosophy of Religion (Bellingham, Washington) 1986 Instructor, Pew Younger Scholars Seminar, 1995, 1999 Co-director summer seminar on nature in belief, Calvin College, July, 2004 Other E. Harris Harbison Award for Distinguished Teaching (Danforth Foundation), 1968 Member, Council for Philosophical Studies, 1968-74 William Evans Visiting Fellow University of Otago (New Zealand) 1991 Mentor, Collegium, Fairfield University 1993 The James A. -

Studia Culturologica Series

volume 22, autumn-winter 2005 studia culturologica series GEORGE GALE OSWALD SCHWEMMER DIETER MERSCH HELGE JORDHEIM JAN RADLER JEAN-MARC T~TAZ DIMITRI GINEV ROLAND BENEDIKTER Maison des Sciences de I'Homme et de la Societe George Gcrle LEIBNIZ, PETER THE GREAT, AND TIIE MOUERNIZAIION OF RUSSIA or Adventures of a Philosopher-King in the East Leibniz was the modern world's lirst Universal C'itizen. Ilespite being based in a backwater northern German principalit). Leibniz' scliolarly and diploniatic missions took liim - sometimes for extendud stays -- everywhere i~nportant:to Paris and Lotidon, to Berlin, to Vien~~nand Konie. And this in a time when travel \vas anything birt easy. Leibniz' intelluctual scope was ecli~ally\vide: his philosophic focus extended all the way ti-om Locke's England to Confi~cius'C'hina, even while his geopolitical interests encom- passed all tlie vast territory from Cairo to Moscow. In short, Leibniz' acti- vities, interests and attention were not in the least hounded by tlie narrow compass of his home base. Our interests, however, must be bounded: to this end, our concern in what follows will Iiniil itself to Leibniz' relations with tlie East, tlie lands beyond the Elbe, the Slavic lands. Not only are these relations topics of intrinsic interest, they have not received anywhere near tlie attention they deserve. Our focus will be the activities of Leibniz himself, the works of the living philosopher, diplomat, and statesman, as he carried them out in his own time. Althoi~ghLeibniz' heritage continues unto today in the form of a pl~ilosophicaltradition, exa~ninationoftliis aspect of Leibnizian influ- ence nli~stawait another day.