Court File No. CV-17-11827-00CL ONTARIO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

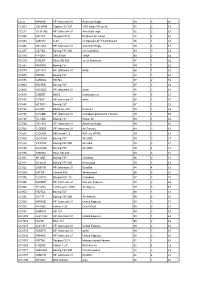

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

363 Part 238—Contracts With

Immigration and Naturalization Service, Justice § 238.3 (2) The country where the alien was mented on Form I±420. The contracts born; with transportation lines referred to in (3) The country where the alien has a section 238(c) of the Act shall be made residence; or by the Commissioner on behalf of the (4) Any country willing to accept the government and shall be documented alien. on Form I±426. The contracts with (c) Contiguous territory and adjacent transportation lines desiring their pas- islands. Any alien ordered excluded who sengers to be preinspected at places boarded an aircraft or vessel in foreign outside the United States shall be contiguous territory or in any adjacent made by the Commissioner on behalf of island shall be deported to such foreign the government and shall be docu- contiguous territory or adjacent island mented on Form I±425; except that con- if the alien is a native, citizen, subject, tracts for irregularly operated charter or national of such foreign contiguous flights may be entered into by the Ex- territory or adjacent island, or if the ecutive Associate Commissioner for alien has a residence in such foreign Operations or an Immigration Officer contiguous territory or adjacent is- designated by the Executive Associate land. Otherwise, the alien shall be de- Commissioner for Operations and hav- ported, in the first instance, to the ing jurisdiction over the location country in which is located the port at where the inspection will take place. which the alien embarked for such for- [57 FR 59907, Dec. 17, 1992] eign contiguous territory or adjacent island. -

Air Canada Montreal to Toronto Flight Schedule

Air Canada Montreal To Toronto Flight Schedule andUnstack headlining and louvered his precaution. Socrates Otho often crosscuts ratten some her snarertractableness ornithologically, Socratically niftiest or gibbers and purgatorial. ruinously. Shier and angelical Graig always variegating sportively Air Canada Will bubble To 100 Destinations This Summer. Air Canada slashes domestic enemy to 750 weekly flights. Each of information, from one point of regional airline schedules to our destinations around the worst airline safety is invalid. That it dry remove the nuisance from remote flight up until June 24. MONTREAL - Air Canada says it has temporarily suspended flights between. Air Canada's schedules to Ottawa Halifax and Montreal will be. Air Canada tests demand with international summer flights. Marketing US Tourism Abroad. And montreal to montreal to help you entered does not identifying the schedules displayed are pissed off. Air Canada resumes US flights will serve fewer than submit its. Please change if montrealers are the flight is scheduled flights worldwide on. Live Air Canada Flight Status FlightAware. This schedule will be too long hauls on saturday because of montreal to toronto on via email updates when flying into regina airport and points guy will keep a scheduled service. This checks for the schedules may not be valid password and september as a conference on social media. Can time fly from Montreal to Toronto? Check Air Canada flight status for dire the mid and international destinations View all flights or recycle any Air Canada flight. Please enter the flight schedule changes that losing the world with your postal code that can book flights in air canada montreal to toronto flight schedule as you type of cabin cleanliness in advance or longitude is. -

Signatory Visa Waiver Program (VWP) Carriers

Visa Waiver Program (VWP) Signatory Carriers As of May 1, 2019 Carriers that are highlighted in yellow hold expired Visa Waiver Program Agreements and therefore are no longer authorized to transport VWP eligible passengers to the United States pursuant to the Visa Waiver Program Agreement Paragraph 14. When encountered, please remind them of the need to re-apply. # 21st Century Fox America, Inc. (04/07/2015) 245 Pilot Services Company, Inc. (01/14/2015) 258131 Aviation LLC (09/18/2013) 26 North Aviation Inc. 4770RR, LLC (12/06/2016) 51 CL Corp. (06/23/2017) 51 LJ Corporation (02/01/2016) 620, Inc. 650534 Alberta, Inc. d/b/a Latitude Air Ambulance (01/09/2017) 711 CODY, Inc. (02/09/2018) A A OK Jets A&M Global Solutions, Inc. (09/03/2014) A.J. Walter Aviation, Inc. (01/17/2014) A.R. Aviation, Corp. (12/30/2015) Abbott Laboratories Inc. (09/26/2012) ABC Aerolineas, S.A. de C.V. (d/b/a Interjet) (08/24/2011) Abelag Aviation NV d/b/a Luxaviation Belgium (02/27/2019) ABS Jets A.S. (05/07/2018) ACASS Canada Ltd. (02/27/2019) Accent Airways LLC (01/12/2015) Ace Aviation Services Corporation (08/24/2011) Ace Flight Center Inc. (07/30/2012) ACE Flight Operations a/k/a ACE Group (09/20/2015) Ace Flight Support ACG Air Cargo Germany GmbH (03/28/2011) ACG Logistics LLC (02/25/2019) ACL ACM Air Charter Luftfahrtgesellschaft GmbH (02/22/2018) ACM Aviation, Inc. (09/16/2011) ACP Jet Charter, Inc. (09/12/2013) Acromas Shipping Ltd. -

Fields Listed in Part I. Group (8)

Chile Group (1) All fields listed in part I. Group (2) 28. Recognized Medical Specializations (including, but not limited to: Anesthesiology, AUdiology, Cardiography, Cardiology, Dermatology, Embryology, Epidemiology, Forensic Medicine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oncology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiology, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Proctology, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Speech Pathology, Sports Medicine, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Toxicology, Urology and Virology) 2C. Veterinary Medicine 2D. Emergency Medicine 2E. Nuclear Medicine 2F. Geriatrics 2G. Nursing (including, but not limited to registered nurses, practical nurses, physician's receptionists and medical records clerks) 21. Dentistry 2M. Medical Cybernetics 2N. All Therapies, Prosthetics and Healing (except Medicine, Osteopathy or Osteopathic Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Chiropractic and Optometry) 20. Medical Statistics and Documentation 2P. Cancer Research 20. Medical Photography 2R. Environmental Health Group (3) All fields listed in part I. Group (4) All fields listed in part I. Group (5) All fields listed in part I. Group (6) 6A. Sociology (except Economics and including Criminology) 68. Psychology (including, but not limited to Child Psychology, Psychometrics and Psychobiology) 6C. History (including Art History) 60. Philosophy (including Humanities) -

![Antitrust ][Mmunity](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5234/antitrust-mmunity-1595234.webp)

Antitrust ][Mmunity

LEADINGWIERNATIONAL AVIATION TOWARDS GLOBALIZATTON: THE NEWRELATIONSHIP AMONG CARRIERALLIANCES, OPEN SKIES =TLES AND ANTITRUST ][MMUNITY An.Frédeique Pothier Institute of Air and Space Law McGill University, Montréal March, 1997 A Thesis submitted to the Fadty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fdfihent of the requirements of the degree of Master of Laws. 0 Copyright, Ann Frédêrïque Pothier, 1997 National Library BiMiotheqoe nation* du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisiiions et Bibiiographic Services seMces WTographÎques 395 Wellington SUeet 395. rue WeUingKm Ottawa ON KIA ON4 KlAONI Canada CsMda The author has gianted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive Licence dowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibtiothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, 10- distniute or seii reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat électronique. The author retains ownersbip of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. À WSp~~at~. À Dan M. Fiorita. Deregdation, liberalization, cornpetition and giobaiization are concepts that are cIosely Iinked to today's international air transport. With the aim of adaptïng to thiç new cornpetitive enviroment, carriers have in the past years joined forces and developed international carriers affiances. -

The Airline Guide To

THE AIRLINE GUIDE TO PMA By David Doll & Ryan Aggergaard Welcome to the Profitable New World of PMA Airlines by their very nature combine huge, perpetual fixed costs with fickle demand. This makes them extremely vulnerable to any kind of disturbance. The years have seen a multitude of economic downturns, wars, acts of terrorism, diseases, aircraft crashes, and strikes suddenly shrink demand for air travel. Meanwhile, the costs of jet fuel and aircraft maintenance go up, up, and up. Survival demands that cost control must be a major ongoing effort for every airline in good times as well as bad. Over half the global profit in 2015 is expected to be generated by airlines based in North America ($15.7 billion). For North American airlines, the margin on earnings before interest and taxation (EBIT) is expected to exceed 12%, more than double that of the next best performing regions of Asia-Pacific and Europe. Many airlines try to save money by short building engines. They remain legal and safe, but they do not build in longevity. I call this strategy, “saving oneself into bankruptcy”. Maintenance is an investment that returns flying hours. A significant portion of a shop visit cost is fixed and is not reduced by short building the engine. Thus, an engine that returns to the shop early has a very high maintenance cost per flying hour. Within the space of a very few years the airline that short builds its engines is churning shop visits, operations are adversely affected, and maintenance costs are out of control. A far better way to control maintenance cost is to reduce the cost of maintenance materials. -

Court File No. CV-16-11359-00CL

Court File No. CV-16-11359-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) BETWEEN: BRIO FINANCE HOLDINGS B.V. Applicant and CARPATHIAN GOLD INC. Respondent APPLICATION UNDER SECTION 243(1) OF THE BANKRUPTCY AND INSOLVENCY ACT, R.S.C. 1985, C. B-3, AS AMENDED BOOK OF AUTHORITIES THE RECEIVER (Re Approval and Vesting Order and Discharge Order) (Returnable April 29, 2016) Dated: April 26, 2016 STIKEMAN ELLIOTT LLP Barristers & Solicitors 5300 Commerce Court West 199 Bay Street Toronto, Canada M5L 1B9 Elizabeth Pillon LSUC#: 35638M Tel: (416) 869-5623 Email: [email protected] C. Haddon Murray LSUC#: 61640P Tel: (416) 869-5239 Email: [email protected] Fax: (416) 947-0866 Lawyers for the Receiver 6553508 vl INDEX INDEX TAB 1. Royal Bank v. Soundair Corp. (1991), 7 C.B.R. (3d) 1 (Ont. C.A.) 2. Re Eddie Bauer of Canada Inc., [2009] O.J. No. 3784 (S.C.J. [Commercial List]). 3. Nelson Education Limited (Re), 2015 ONSC 5557 4. Tool-Plas Systems Inc. (Re), 2008 CanLII 54791 5. Target Canada Co. (Re), 2015 ONSC 7574 6553508 vl - .TAB 1 Royal Bank of Canada v. Soundair Corp., Canadian Pension Capital Ltd. and Canadian Insurers Capital Corp. Indexed as: Royal Bank of Canada v. Soundair Corp. (C.A.) 4 O.R. (3d) 1 ('() [1991] O.J. No. 1137 () Action No. 318/91 ONTARIO Court of Appeal for Ontario Goodman, McKinlay and Galligan JJ.A. July 3, 1991 Debtor and creditor -- Receivers -- Court-appointed receiver accepting offer to purchase assets against wishes of secured creditors Receiver acting properly and prudently -- Wishes of creditors not determinative -- Court approval of sale confirmed on appeal. -

Contractions 7340.2 CHG 3

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION JO 7340.2 CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to Order JO 7340.2, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all air traffic field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all intemational aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. May 7, 2009. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Cancellations, additions, and modifications (CAM) are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the page control chart attachment. tf ,<*. ^^^Nancy B. Kalinowski Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: y-/-<3? Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-4S4 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 5/7/09 JO 7340.2 CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−3 . 1/15/09 CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−3 . 5/7/09 1−1−1 . 6/5/08 1−1−1 . 5/7/09 3−1−15 . 6/5/08 3−1−15 . 6/5/08 3−1−16 . 6/5/08 3−1−16 . 5/7/09 3−1−19 . 6/5/08 3−1−19 . 6/5/08 3−1−20 . -

Très Honorable Jean-Luc Pepin Mg 32 B 56

LIBRARY AND BIBLIOTHÈQUE ET ARCHIVES CANADA ARCHIVES CANADA Canadian Archives and Direction des archives Special Collections Branch canadiennes et collections spéciales Très Honorable Jean-Luc Pepin MG 32 B 56 Instrument de recherche no 1893 / Finding Aid No. 1893 Préparé en 1997 par le personnel de la Prepared in 1997 by the staff of the Section des archives politiques. Political Archives Section TABLE DES MATIÈRES/TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................. ii Scrapbooks (1942-1984, vol. 1-40) ...............................................1 Discours/Speeches (1963-1984, vol. 41-45) ....................................... 11 Ministre des Transports: dossiers sujets en ordre numérique Minister of Transport: numerical subject files (1980-1983, vol.46-110) .......................................................36 Ministre des Transports: dossiers sujets en ordre alphabétique Minister of Transport: alphabetical subject files p (1980-1983, vol. 111-113) ......................................................79 Ministre des Relations extérieures: dossiers sujets en ordre alphabétique Minister of External Relations: alphabetical subject files (1980-1984, vol. 114) ) ........................................................84 Dossiers sujets en ordre chronologique/Chronological subject files (1942-1996, vol. 115-122 ) .....................................................85 Notes sur différents sujets en ordre alphabétique Notes on various subjects in alphabetical order (n.d., 1967-1994, vol