BOOK of AUTHORITIES of the APPLICANTS Returnable September 1, 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

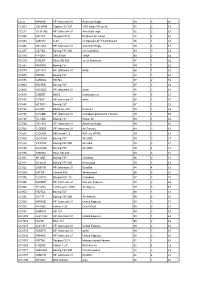

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

363 Part 238—Contracts With

Immigration and Naturalization Service, Justice § 238.3 (2) The country where the alien was mented on Form I±420. The contracts born; with transportation lines referred to in (3) The country where the alien has a section 238(c) of the Act shall be made residence; or by the Commissioner on behalf of the (4) Any country willing to accept the government and shall be documented alien. on Form I±426. The contracts with (c) Contiguous territory and adjacent transportation lines desiring their pas- islands. Any alien ordered excluded who sengers to be preinspected at places boarded an aircraft or vessel in foreign outside the United States shall be contiguous territory or in any adjacent made by the Commissioner on behalf of island shall be deported to such foreign the government and shall be docu- contiguous territory or adjacent island mented on Form I±425; except that con- if the alien is a native, citizen, subject, tracts for irregularly operated charter or national of such foreign contiguous flights may be entered into by the Ex- territory or adjacent island, or if the ecutive Associate Commissioner for alien has a residence in such foreign Operations or an Immigration Officer contiguous territory or adjacent is- designated by the Executive Associate land. Otherwise, the alien shall be de- Commissioner for Operations and hav- ported, in the first instance, to the ing jurisdiction over the location country in which is located the port at where the inspection will take place. which the alien embarked for such for- [57 FR 59907, Dec. 17, 1992] eign contiguous territory or adjacent island. -

Fields Listed in Part I. Group (8)

Chile Group (1) All fields listed in part I. Group (2) 28. Recognized Medical Specializations (including, but not limited to: Anesthesiology, AUdiology, Cardiography, Cardiology, Dermatology, Embryology, Epidemiology, Forensic Medicine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oncology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiology, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Proctology, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Speech Pathology, Sports Medicine, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Toxicology, Urology and Virology) 2C. Veterinary Medicine 2D. Emergency Medicine 2E. Nuclear Medicine 2F. Geriatrics 2G. Nursing (including, but not limited to registered nurses, practical nurses, physician's receptionists and medical records clerks) 21. Dentistry 2M. Medical Cybernetics 2N. All Therapies, Prosthetics and Healing (except Medicine, Osteopathy or Osteopathic Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Chiropractic and Optometry) 20. Medical Statistics and Documentation 2P. Cancer Research 20. Medical Photography 2R. Environmental Health Group (3) All fields listed in part I. Group (4) All fields listed in part I. Group (5) All fields listed in part I. Group (6) 6A. Sociology (except Economics and including Criminology) 68. Psychology (including, but not limited to Child Psychology, Psychometrics and Psychobiology) 6C. History (including Art History) 60. Philosophy (including Humanities) -

![Antitrust ][Mmunity](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5234/antitrust-mmunity-1595234.webp)

Antitrust ][Mmunity

LEADINGWIERNATIONAL AVIATION TOWARDS GLOBALIZATTON: THE NEWRELATIONSHIP AMONG CARRIERALLIANCES, OPEN SKIES =TLES AND ANTITRUST ][MMUNITY An.Frédeique Pothier Institute of Air and Space Law McGill University, Montréal March, 1997 A Thesis submitted to the Fadty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fdfihent of the requirements of the degree of Master of Laws. 0 Copyright, Ann Frédêrïque Pothier, 1997 National Library BiMiotheqoe nation* du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisiiions et Bibiiographic Services seMces WTographÎques 395 Wellington SUeet 395. rue WeUingKm Ottawa ON KIA ON4 KlAONI Canada CsMda The author has gianted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive Licence dowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibtiothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, 10- distniute or seii reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat électronique. The author retains ownersbip of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. À WSp~~at~. À Dan M. Fiorita. Deregdation, liberalization, cornpetition and giobaiization are concepts that are cIosely Iinked to today's international air transport. With the aim of adaptïng to thiç new cornpetitive enviroment, carriers have in the past years joined forces and developed international carriers affiances. -

Court File No. CV-16-11359-00CL

Court File No. CV-16-11359-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) BETWEEN: BRIO FINANCE HOLDINGS B.V. Applicant and CARPATHIAN GOLD INC. Respondent APPLICATION UNDER SECTION 243(1) OF THE BANKRUPTCY AND INSOLVENCY ACT, R.S.C. 1985, C. B-3, AS AMENDED BOOK OF AUTHORITIES THE RECEIVER (Re Approval and Vesting Order and Discharge Order) (Returnable April 29, 2016) Dated: April 26, 2016 STIKEMAN ELLIOTT LLP Barristers & Solicitors 5300 Commerce Court West 199 Bay Street Toronto, Canada M5L 1B9 Elizabeth Pillon LSUC#: 35638M Tel: (416) 869-5623 Email: [email protected] C. Haddon Murray LSUC#: 61640P Tel: (416) 869-5239 Email: [email protected] Fax: (416) 947-0866 Lawyers for the Receiver 6553508 vl INDEX INDEX TAB 1. Royal Bank v. Soundair Corp. (1991), 7 C.B.R. (3d) 1 (Ont. C.A.) 2. Re Eddie Bauer of Canada Inc., [2009] O.J. No. 3784 (S.C.J. [Commercial List]). 3. Nelson Education Limited (Re), 2015 ONSC 5557 4. Tool-Plas Systems Inc. (Re), 2008 CanLII 54791 5. Target Canada Co. (Re), 2015 ONSC 7574 6553508 vl - .TAB 1 Royal Bank of Canada v. Soundair Corp., Canadian Pension Capital Ltd. and Canadian Insurers Capital Corp. Indexed as: Royal Bank of Canada v. Soundair Corp. (C.A.) 4 O.R. (3d) 1 ('() [1991] O.J. No. 1137 () Action No. 318/91 ONTARIO Court of Appeal for Ontario Goodman, McKinlay and Galligan JJ.A. July 3, 1991 Debtor and creditor -- Receivers -- Court-appointed receiver accepting offer to purchase assets against wishes of secured creditors Receiver acting properly and prudently -- Wishes of creditors not determinative -- Court approval of sale confirmed on appeal. -

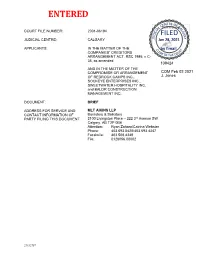

Bench Brief Re: Monitor's Application

Clerk’s Stamp COURT FILE NUMBER: 2001-06194 JUDICIAL CENTRE: CALGARY APPLICANTS: IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, RSC 1985, c C- 36, as amended 109424 AND IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT COM Feb 02 2021 OF REDROCK CAMPS INC., J. Jones SOCKEYE ENTERPRISES INC., SWEETWATER HOSPITALITY INC. and BALDR CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT INC. DOCUMENT: BRIEF ADDRESS FOR SERVICE AND MLT AIKINS LLP CONTACT INFORMATION OF Barristers & Solicitors PARTY FILING THIS DOCUMENT: 2100 Livingston Place – 222 3rd Avenue SW Calgary, AB T2P 0B4 Attention: Ryan Zahara/Catrina Webster Phone: 403.693.5420/403.693.4347 Facsimile: 403.508.4349 File: 0128056.00002 23832757 - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I – INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 3 PART II – STATEMENT OF FACTS .......................................................................................... 4 PART III - ISSUE ......................................................................................................................13 PART IV – LAW AND ARGUMENT ...........................................................................................13 A. Approval of Asset Sales ............................................................................................................... 13 B. Approval of the Reverse Vesting Order ...................................................................................... 14 C. The Purchase Agreement is Appropriate in the Circumstances ............................................. -

363 Part 238—Contracts with Transportation Lines

Immigration and Naturalization Service, Justice § 238.3 (2) The country where the alien was mented on Form I±420. The contracts born; with transportation lines referred to in (3) The country where the alien has a section 238(c) of the Act shall be made residence; or by the Commissioner on behalf of the (4) Any country willing to accept the government and shall be documented alien. on Form I±426. The contracts with (c) Contiguous territory and adjacent transportation lines desiring their pas- islands. Any alien ordered excluded who sengers to be preinspected at places boarded an aircraft or vessel in foreign outside the United States shall be contiguous territory or in any adjacent made by the Commissioner on behalf of island shall be deported to such foreign the government and shall be docu- contiguous territory or adjacent island mented on Form I±425; except that con- if the alien is a native, citizen, subject, tracts for irregularly operated charter or national of such foreign contiguous flights may be entered into by the Ex- territory or adjacent island, or if the ecutive Associate Commissioner for alien has a residence in such foreign Operations or an Immigration Officer contiguous territory or adjacent is- designated by the Executive Associate land. Otherwise, the alien shall be de- Commissioner for Operations and hav- ported, in the first instance, to the ing jurisdiction over the location country in which is located the port at where the inspection will take place. which the alien embarked for such for- [57 FR 59907, Dec. 17, 1992] eign contiguous territory or adjacent island. -

Court File No. CV-17-11827-00CL ONTARIO

Court File No. CV-17-11827-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE BETWEEN : DUCA FINANCIAL SERVICES CREDIT LTD. Applicant - and - 2203824 ONTARIO INC. Respondent BRIEF OF AUTHORITIES OF THE RECEIVER, MSI SPERGEL INC. DEVRY SMITH FRANK LLP Lawyers & Mediators 95 Barber Greene Road, Suite 100 Toronto, ON M3C 3E9 LAWRENCE HANSEN LSUC No. 41098W SARA MOSADEQ LSUC No. 67864K Tel.: 416-449-1400 Fax: 416- 449-7071 Lawyers for the receiver msi Spergel Inc. Court File No. CV-17-11827-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE BETWEEN : DUCA FINANCIAL SERVICES CREDIT LTD. Applicant - and - 2203824 ONTARIO INC. Respondent INDEX TAB AUTHORITY 1 Royal Bank of Canada v. Soundair Corp., 1991 Canlii 2727 (ON CA) 2 Sierra Club of Canada v. Canada (Minister of Finance), [2002] 2 SCR 522, 2002 SCC 41 (CanLii) 3 Delview Construction Ltd. v. Meringolo, 71 O.R (3d) 1, ONCA, 4 Thomas Gold Pettinghill LLP v. Ani-Wall Concrete Forming Inc., 2012 ONSC 2182 (CanLii) 5 Budinsky v. The Breakers East Inc., 1993 canlii 5442 (ONSC) 6 Royal Trust Co. v. Montex Apparel Industries Ltd. (1972), 17 C.B.R. (N.S) 45 (Ont. C.A) TAB 1 Royal Bank of Canada v. Soundair Corp., Canadian Pension Capital Ltd. and Canadian Insurers Capital Corp. Indexed as: Royal Bank of Canada v. Soundair Corp. (C.A.) 4 O.R. (3d) 1 [1991] O.J. No. 1137 Action No. 318/91 1991 CanLII 2727 (ON CA) ONTARIO Court of Appeal for Ontario Goodman, McKinlay and Galligan JJ.A. July 3, 1991 Debtor and creditor -- Receivers -- Court-appointed receiver accepting offer to purchase assets against wishes of secured creditors -- Receiver acting properly and prudently -- Wishes of creditors not determinative -- Court approval of sale confirmed on appeal. -

Westjet and MAA Best Practices for Siebel Applications on Oracle

WestJet: Siebel on Exadata Floyd Manzara [email protected] Kris Trzesicki [email protected] WestJet: Overview THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY IS TOUGH “If I’d been at Kitty Hawk in 1903 when Orville Wright took off, I would have been farsighted enough, and public-spirited enough – I owed this to future capitalists – to shoot him down.” - Warren Buffet WestJet: Overview Canadian airlines operating today Adler Aviation Aklak Air Cargojet Airways KD Air North-Wright Airways Sunwing Airlines Aeropro Alberta Citylink Central Mountain Air Keewatin Air Orca Airways Superior Airways Air Canada Aldair Aviation CHC Helicopter Kelowna Flightcraft Pacific Coastal Airlines Thunder Airlines Air Canada Jazz Alkan Air Cloud Air Kenn Borek Air Pascan Aviation Tofino Air Air Canada Jetz Alta Flights Corporate Express Keystone Air Service Perimeter Aviation Trans Capital Air Air Creebec Arctic Sunwest Cougar Helicopters Kivalliq Air Porter Airlines Transwest Air Air Express Ontario Charters Craig Air Kootnay Direct Airlines Prince Edward Air Universal Helicopters Air Georgian Bar XH Air Enerjet Lakeland Aviation Pronto Airways Vancouver Island Air Air Inuit BCWest Air Enterprise Airlines LR Helicopters Inc. Provincial Airlines Voyageur Airways Air Labrador Bearskin Airlines First Air Maritime Air Charter Regional 1 Wasaya Airways Air Mikisew Brock Air Services Flair Airlines Morningstar Air Salt Spring Air West Coast Air Air North Buffalo Airways Green Air Express SkyLink Aviation West Wind Aviation Air Nunavut Calm Air Harbour Air Nolinor Aviation SkyNorth -

Netletter #1429 | January 11, 2020 Finnair Registration OH-LYC By

NetLetter #1429 | January 11, 2020 Finnair Registration OH-LYC by Michel Gilliand Welcome to the NetLetter, an Aviation based newsletter for Air Canada, TCA, CP Air, Canadian Airlines and all other Canadian based airlines that once graced the Canadian skies. The NetLetter is published on the second and fourth weekend of each month. If you are interested in Canadian Aviation History, and vintage aviation photos, especially as it relates to Trans-Canada Air Lines, Air Canada, Canadian Airlines International and their constituent airlines, then we're sure you'll enjoy this newsletter. Our website is located at www.thenetletter.net Please click the links below to visit our NetLetter Archives and for more info about the NetLetter. NetLetter News We always welcome feedback about Air Canada (including Jazz and Rouge) from our subscribers who wish to share current events, memories and photographs. Particularly if you have stories to share from one of the legacy airlines: Canadian Airlines, CP Air, Pacific Western, Eastern Provincial, Wardair, Nordair, Transair and many more (let us know if we have omitted your airline). Please feel free to contact us at [email protected] Welcome to 2020! You will notice that we have made a few small changes beginning with this issue. We have updated the signature image of the current 'NetLetter Team' and acknowledge our founder, Vesta Stevenson, and administrator/designer, Alan Rust. Their vision continues to contribute to each issue. We have also added two new sections: Remember When: We invite subscribers to share their personal experiences that have become treasured memories from their aviation careers. -

Court File No. CV-18-601307-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR

Court File No. CV-18-601307-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE - COMMERCIAL LIST IN THE MATTER OF RECEIVERSHIP OF SAGE GOLD INC. and IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION PURSUANT TO SECTION 243(1) OF THE BANKRUPTCY AND INSOLVENCY ACT, R.S.C. 1985, C. B-3, AS AMENDED; AND SECTION 101 OF THE COURTS OF JUSTICE ACT, R.S.O. 1990, C. C.43, AS AMENDED BOOK OF AUTHORITIES OF THE RECEIVER, DELOITTE RESTRUCTURING INC. (returnable December 19, 2019) December 16, 2019 MCMILLAN LLP Brookfield Place 181 Bay Street, Suite 4400 Toronto, ON, M5J 2T3 Wael Rostom [email protected] Tel: 416-865-7790 Stephen Brown-Okruhlik [email protected] Tel: 416-865-7043 Fax: 416-865-7048 Lawyers for the Receiver, Deloitte Restructuring Inc. TO: SERVICE LIST Index INDEX TAB Third Eye Capital Corporation v. Ressources Dianor Inc./Dianor 1 Resources Inc., 2019 ONCA 508 Royal Bank v. Soundair Corp., [1991] O.J. No. 1137. 2 Playdium Entertainment Corp., Re, [2001] O.J. No. 4252. 3 Playdium Entertainment Corp., Re, [2001] O.J. No. 4459. 4 Re: Century Services Inc., 2010 SCC 60. 5 Sierra Club of Canada v. Canada (Minister of Finance), 2002 SCC 41. 6 GE Canada Real Estate Financing Business Property Co. v. 1262354 7 Ontario Inc., 2014 ONSC 1173. Tab 1 Third Eye Capital Corporation v. Ressources Dianor..., 2019 ONCA 508, 2019... 2019 ONCA 508, 2019 CarswellOnt 9683, 306 A.C.W.S. (3d) 235, 3 R.P.R. (6th) 175... Most Negative Treatment: Check subsequent history and related treatments.