The Police Dog: History, Breeds and Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beauceron

The Beauceron The Beauceron, also known as Berger de Beauce and Bas Rouge, is the largest of the French sheepdogs and was developed solely in France with no foreign crosses. The Beauceron is closely related to the longhaired Briard or Berger de Brie. The first mention of a dog which matches the Beauceron’s description is found in a manuscript dated 1587. In 1809 Abbé Rozier wrote an article on French herding dogs. It was he who first described the differences in type and used the terms Berger de la Brie for long coated dogs and Berger de la Beauce for short coated dogs. The name Beauceron was used for the first time by Pierre Megnin in his 1888 book on war dogs and the first Berger de Beauce was registered with the Societe Central Canine in September 1893. The French Club Les Amis du Beauceron (CAB), was founded in 1922 by Pierre Megnin and he together with Emmanuel Boulet developed the original breed standard for the Beauceron. The CAB has since guided the development of the breed in its native France, always keeping a watchful eye on the preservation of the breed’s herding and working ability. During the early part of the 19th century large flocks of sheep were common and the Beauceron was indispensable for the shepherds of France; two dogs were sufficient to tend to flocks of 200 to 300 head of sheep. Sheep production experienced a sharp decline during the later half of the 19th century and by the second half of the 20th century was only a phantom of its past. -

Frequently Asked Questions

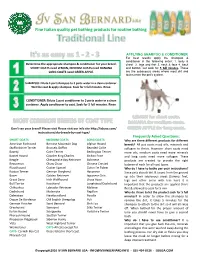

APPLYING SHAMPOO & CONDITIONER For best results apply the shampoo & conditioner in the following order: 1. belly & Determine the appropriate shampoo & conditioner for your breed. chest 2. legs and feet 3. neck & face 4. back SHORT COATS need LEMON, MEDIUM COATS need BANANA and bottom. Let soak for 5 full minutes. These LONG COATS need GREEN APPLE. are the sebaceous areas where most dirt and toxins enter the pet’s system. SHAMPOO: Dilute 1 part shampoo to 3 parts water in a clean container. Wet the coat & apply shampoo. Soak for 5 full minutes. Rinse. CONDITIONER: Dilute 1 part conditioner to 3 parts water in a clean container. Apply conditioner to coat. Soak for 5 full minutes. Rinse. Don’t see your breed? Please visit Please visit our info site http://isbusa.com/ instructions/akc-breeds-by-coat-type/ Frequently Asked Questions: SHORT COATS MEDIUM COATS LONG COATS Why are there different products for different American Foxhound Bernese Mountain Dog Afghan Hound breeds? All pet coats need oils, minerals and Staffordshire Terrier Brussels Griffon Bearded Collie collagen to thrive. However short coats need Basenji Cairn Terrier Bedlington Terrier more oils, medium coats need more minerals Basset Hound Cavalier King Charles Bichon Frise and long coats need more collagen. These Beagle Chesapeake Bay Retriever Bolonese products are created to provide the right Beauceron Chow Chow Chinese Crested balance of each for all coat types. Bloodhound Cocker Spaniel Coton De Tulear Why do I have to bathe per your instructions? Boston Terrier German Shepherd Havanese Since pets absorb dirt & toxins from the ground Boxer Golden Retriever Japanese Chin up into their sebaceous areas (tummy, feet, Great Dane Irish Wolfhound Lhasa Apso legs and other areas with less hair) it is Bull Terrier Keeshond Longhaired Dachshund important that the products are applied there Chihuahua Labrador Retriever Maltese first & allowed to soak for 5 min. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force's Current Understanding Of

Hülsmeyer et al. BMC Veterinary Research (2015) 11:175 DOI 10.1186/s12917-015-0463-0 CORRESPONDENCE Open Access International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force’s current understanding of idiopathic epilepsy of genetic or suspected genetic origin in purebred dogs Velia-Isabel Hülsmeyer1*, Andrea Fischer1, Paul J.J. Mandigers2, Luisa DeRisio3, Mette Berendt4, Clare Rusbridge5,6, Sofie F.M. Bhatti7, Akos Pakozdy8, Edward E. Patterson9, Simon Platt10, Rowena M.A. Packer11 and Holger A. Volk11 Abstract Canine idiopathic epilepsy is a common neurological disease affecting both purebred and crossbred dogs. Various breed-specific cohort, epidemiological and genetic studies have been conducted to date, which all improved our knowledge and general understanding of canine idiopathic epilepsy, and in particular our knowledge of those breeds studied. However, these studies also frequently revealed differences between the investigated breeds with respect to clinical features, inheritance and prevalence rates. Awareness and observation of breed-specific differences is important for successful management of the dog with epilepsy in everyday clinical practice and furthermore may promote canine epilepsy research. The following manuscript reviews the evidence available for breeds which have been identified as being predisposed to idiopathic epilepsy with a proven or suspected genetic background, and highlights different breed specific clinical features (e.g. age at onset, sex, seizure type), treatment response, prevalence rates and proposed inheritance reported in the literature. In addition, certain breed-specific diseases that may act as potential differentials for idiopathic epilepsy are highlighted. Keywords: Idiopathic epilepsy, Dog, Breed, Epilepsy prevalence, Epileptic seizure Introduction in part underlying genetic backgrounds (see also Tables 1 Canine idiopathic epilepsy is a common neurological and 2) [5, 6]. -

The History of the BERGER PICARD

The History of the BERGER PICARD By Betsy Richards hought to be the oldest upright ears, resembling in many ways a Beauce, or Beaceron). The mid-length of the French Sheep- Berger Picard of today. coat was ignored for some time, but final- dogs, the Berger Picard Of course it is not certain that the ly recognized as the Berger de Picardie was brought to northern Berger Picard originates strictly from the (or Picard). France and the Pas de Picardie region of France; it is possible, Although the Berger Picard made an Calais during the second even probable, that they were widespread appearance at the first French dog show TCeltic invasion of Gaul around 400 BC. as harsh-coated sheep and cattle dogs in 1863 and were judged in the same class Sheepdogs resembling Berger Picards were typical throughout northwestern as the Beaucerons and Briards, the breed's have been depicted for centuries in tapes- Europe. Some experts insist that this breed rustic appearance did not result in popu- tries, engravings and woodcuts. is related to the more well-known Briard larity as a show dog. In 1898 there was One renowned painting in the Bergerie and Beauceron, while others believe it proof that the Picard was a recognizable Nationale at Rambouillet (the National shares a common origin with Dutch and breed but it was tricolor, piebald with red Sheepfold of France) dating to the start Belgian Shepherds. brown markings. of the 19th century, shows the 1st Master Around the mid-19th century, dogs Picards would continue to be shown Shepherd, Clément Delorme, in the com- used for herding were initially classified and participate in herding trials but strug- pany of a medium-sized, strong-boned dog as one of two types: long hair (Berger de gled for recognition. -

Ranked by Temperament

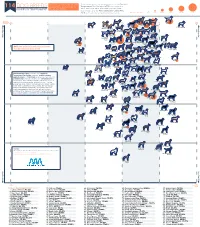

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

Belgian Shepherd and Dutch Shepherd

Belgian Shepherd and Dutch Shepherd HISTORY AND CURRENT TOPICS Jean-Marie Vanbutsele Belgian Dogs Publications BELGIUM Copyright © 2017 by Jean-Marie Vanbutsele. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, dis- tributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photo- copying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, with- out the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non- commercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. Belgian Dogs Publications Donkereham 27 1880 Kapelle-op-den-Bos, Belgium www.belgiandogs.be Book layout and translation: Pascale Vanbutsele Cover image: Dutch Shepherds Aloha kãkou Lani Lotje and Aloha kãkou Riek Wai-Kìkì, photo by Iris Wyss, Switzerland Belgian Shepherd and Dutch Shepherd/ Jean-Marie Vanbutsele —1st ed. Legal deposit: D/2017/9.508/2 ISBN 978-9-0827532-1-9 BISAC: PET008000 PETS / Reference Contents The Belgian Shepherd, History and Current Topics .....................1 The death of Adolphe Reul ...................................................................... 1 The origins of the Belgian Shepherd Dog.............................................. 7 ‘White’ in the Groenendaels .................................................................55 The brindle Belgian Shepherds .............................................................58 Judgements and statements from the Huyghebaert brothers ..........62 -

(FCI) Standard

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) SECRETARIAT GENERAL: 13, Place Albert 1er B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique) ______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ 19.04.2002/ EN _______________________________________________________________ FCI-Standard N° 15 CHIEN DE BERGER BELGE (Belgian Shepherd Dog) 2 TRANSLATION: Mrs. Jeans-Brown, revised by Dr. R. Pollet. Official language (FR). ORIGIN: Belgium. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF OFFICIAL VALID STANDARD: 13.03.2001. UTILISATION: Originally a sheep dog, today a working dog (guarding, defence, tracking, etc.) and an all-purpose service dog, as well as a family dog. FCI-CLASSIFICATION: Group 1 Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle dogs). Section 1 Sheepdogs. With working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY: In Belgium, at the end of the 1800s, there were a great many herding dogs, whose type was varied and whose coats were extremely dissimilar. In order to rationalise this state of affairs, some enthusiastic dog fanciers formed a group and sought guidance from Prof. A. Reul of the Cureghem Veterinary Medical School, whom one must consider to have been the real pioneer and founder of the breed. The breed was officially born between 1891 and 1897. On September 29th, 1891, the Belgian Shepherd Dog Club (Club du Chien de Berger Belge) was founded in Brussels and in the same year on November 15th in Cureghem, Professor A. Reul organised a gathering of 117 dogs, which allowed him to carry out a return and choose the best specimens. In the following years they began a real programme of selection, carrying out some very close interbreeding involving a few stud dogs. By April 3rd, 1892, a first detailed breed standard had already been drawn up by the Belgian Shepherd Dog Club. -

Border Collie) – Germany

Heelwork to Music (Saturday) 1. Monika Gehrke & Nice of you to Come Bye Gigolo Jan (Border Collie) – Germany 2. Sabine Astrom & Promotion Buell Cyclone (Australian Kelpie) – Sweden 3. Marina Stilkenboom & Johnny the Little Black Devil (Schipperke) – Germany 4. Anne Gry Øyeflaten & Havrevingens Ambra (Dutch shepherd) – Norway 5. Minna Yrjana & Like a Hurricane Branwenn Brady (Belgian Shepherd, Malinois) – Finland 6. Anja Jakob & Dancing little Shadow of Fast Crazy Fly (Border Collie) – Germany 7. Olga Kuzina & Almond Chokolat S Chernoy Vody (Australian Shepherd) – Russia 8. Helle Larssen & Littlethorn Avensis (Border Collie) – Denmark 9. Susann Wastenson & Skogvallarens Frodo (Border Collie) – Sweden 10. Carina Persson & Obetes Pop (Border Collie) – Sweden 11. Susanna Ekblom & Cabaroo Dances on Ice (Border Collie) – Finland 12. Lisa Joachimsky & Foxita (Parson Russel terrier) – Germany 13. Kath Hardman & Stillmoor Lady in Red (Border Collie) – Great Britain SHORT BREAK (15 MINUTES) 14. Šimona Drábková & Frederica Alary Aslar (Dobermann) – Czech Republic 15. Christiane Hanchir & Funnyluna van Natterekja (Australian Shepherd) – Belgium 16. Jackie de Jong & Jackie’s Indi (Border Collie) – Great Britain 17. Galina Chogovadze & Sun Light Spot (Border Collie) – Russia 18. Marina Delsink & Gwydion van de Hoge Laer (Belgian Shepherd, Tervueren) – Holland 19. Brigitte van Gestel & Joyful Life van Benvenida’s Joy (Border Collie) – Holland 20. Daniela Šišková & Aurora Piranha Rainy Love (Border Collie) – Czech Republic 21. Anja Christiansen & Feahunden’s Queeny Las (Border Collie) – Denmark 22. Katharina von Dach & Pyla (Border Collie) – Switzerland 23. Monika Olšovská & Arsinoé z Ríše Wa (Border Collie) – Slovakia 24. Sofie Greven & Detania Herfst Roos (Border Collie) – Holland 25. Dylan Smith & Correidhu Chase (Border Collie) – Great Britain 26. -

Catalog Herding September

AMERICAN KENNEL CLUB RULES AND REGULATIONS GOVERN THIS SHOW & TRIAL Permission has been granted by the American Kennel Club for the holding of this event under American Kennel Club Rules and Regulations. James P. Crowley, Secretary. Catalog—All Breed Herding Trial/Test Saturday: September 21, 2013 #2013426409 Sunday: September 22, 2013 #2013426410 Shows will be unbenched and outdoors Show and Trial Hours: 8 am—1 hour after completion of judging Northern California Bearded Collie Fanciers (Licensed by the American JR Herding & Training Facility Kennel Club) 18200 Sycamore Ave Patterson, CA 95363 Show Secretary Pam Fugitt Hetrick 2144 Broadmoor St., Livermore, CA 94551-1150 (925) 294-8965 [email protected] www.abbadogs.com Saturday Judge Rich Godfrey 4172 Black Mountain Rd. La Mesa, CA 91941-7905 Sunday Judge Priscilla Phillips 13025 Broili Dr. Reno, NV 89511-9237 Northern California bearded collie fanciers Licensed by the American Kennel Club Club Officers President Dawn Kinney Vice-President Sharon Prassa Treasurer Libby Myers Buhite Corresponding Secretary Carleen Carver: 3526 Parkland Ave., San Jose, CA 95117 Board of Directors Sara Carver * Barbara Claxton * Shannon Smart The Officers and Board of Directors will also service as the Event Bench Committee SHOW COMMITTEE: Sharon Prassa * Libby Myers-Buhite * Jack Buhite * Pam Harris * Jana Dozet Show Chair Course Director & Chief Stock Handler Sharon Prassa Jill Reifschneider 48—36th Way . Sacramento, CA 95819 (916) 457-7012 [email protected] Trial Classes Limit 20 runs per day Course A Started, Intermediate, Advanced 3-5 Head of Wool/Haired Cross Sheep Test Classes Limit 12 runs per day HT, PT 3 Head of Wool/Haired Cross Sheep I hereby certify to the correctness of the within marked awards and absentees, as taken from the Judge’s Books. -

Sixth Akc Rally® National Championship

SIXTH AKC RALLY® NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP FRIDAY, MARCH 15, 2019 CENTRAL PARK HALL AT EXPO SQUARE 4145 EAST 21ST STREET – TULSA, OK 74114 TWENTY FIFTH AKC NATIONAL OBEDIENCE CHAMPIONSHIP SATURDAY & SUNDAY MARCH 16-17, 2019 AKC MISSION STATEMENT The American Kennel Club is dedicated to upholding the integrity of its Registry, promoting the sport of purebred dogs and breeding for type and function. Founded in 1884, the AKC® and its affiliated organizations advocate for the purebred dog as a family companion, advance canine health and well-being, work to protect the rights of all dog owners and promote responsible dog ownership. AKC OBJECTIVE Advance the study, breeding, exhibiting, running and maintenance of purebred dogs. AKC CORE VALUES We love purebred dogs. We are committed to advancing the sport of the purebred dog. We are dedicated to maintaining the integrity of our Registry. We protect the health and well-being of all dogs. We cherish dogs as companions. We are committed to the interests of dog owners. We uphold high standards for the administration and operation of the AKC. We recognize the critical importance of our clubs and volunteers. SIXTH AKC RALLY® NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP FRIDAY, MARCH 15, 2019 Sponsored in part by Eukanuba™ and J & J Dog Supplies TWENTY FIFTH AKC NATIONAL OBEDIENCE CHAMPIONSHIP SATURDAY & SUNDAY MARCH 16-17, 2019 Permission is granted by the American Kennel Club for the holding of this event under American Kennel Club rules and regulations. 1 Gina M. DiNardo, Secretary AKC BOARD OF DIRECTORS Ronald H. Menaker – Chairman Dr. Thomas M. Davies – Vice Chairman Class of 2019 Class of 2020 • Dr. -

February 2009

Feb 09 OFC-(E) Cover FINAL:OFC-XP 12/23/08 12:19 PM Page 1 CH MOTCH Starbright Passionxttrodinair JDX AGX AGNJ, with owners Ikena Hilmayer and (Jerry Burke not shown) Purina National 2008 HIT Join us again March 13 -15, 2009. December ’08 Board Synopsis • Official ’08 CKC Election & Referendum Results CANADIAN KENNEL CLUB FEBRUARY 2 0 0 9 FOUNDED 1888 2009 Tattoo Lette r i s “ W ” www.ckc.ca Feb 09 IFC-(E) Seeking FINAL:OFC-XP 12/23/08 12:16 PM Page IFC CKC SEEKS STANDING COMMITTEE MEMBERS With the election of a new Board of Directors in This committee is responsible for developing policy, December, a new three-year term has begun. One of the standards, guidelines, and programs related to canine first tasks the new Board faces is the appointment of genetics and hereditary disorders. It includes the devel- several standing committees, whose terms also expire opment of an advanced registry to assist in the future with the previous Board. healthy development of purebred dogs. The committee will also develop policies, standards and guidelines Interested parties should prepare a résumé, along with a related to medical and surgical action performed on brief covering letter, outlining why you are best suited dogs. to serve on the committee. The committee will require individuals with specific Applications should be received no later than March 1, backgrounds: 2009, and will be reviewed by the Board at the regular March 2009 meeting. • 1 must be a veterinarian and 2 must have a back ground in genetics. Forward email applications to [email protected] with the Committee name in the subject line.