International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force's Current Understanding Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living with Your Stabyhoun

LIVING WITH YOUR STABYHOUN MAY 1, 2021 AMERI-CAN STABYHOUN ASSOCIATION CONGRATULATIONS! 4 ORIGIN OF THE STABYHOUN 5 HEALTH 6 Coat 7 Teeth 8 Puppy biting behavior 8 Undesirable critters 9 Worms and other Puppy Parasites 10 Heartworm 12 Vaccinations 14 Female in Season 15 Walking and Running 16 Stairs 16 Warm weather 16 Genetic Defects 17 Canine Hip Dysplasia (CHD) 17 Growing Pains or Elbow Dysplasia? 19 Growing Pains 19 Elbow Dysplasia 19 Epilepsy 20 Steroid Responsive Meningitis-Arteritis (SRMA) 20 Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) 20 Cerebral Dysfunction (CD) 20 Von Willebrands Disease, Type I (VWD-I) 20 NUTRITION 21 Treats 21 Puppy Manual ASA - 1 - Food Bowl Training 21 Commercial Dog Food 22 KIBBLE 22 Always the Same Food? 22 Life Stages and Nutrition 23 Food to Avoid 23 Other 23 DOGS ARE NOT WOLVES 24 DEVELOPMENT AND SOCIALIZATION 25 Vegetative Stage (0-2 weeks) 25 Transitional Stage (2-3 weeks) 25 Primary Socialization Stage (3-5 weeks) 25 Secondary Socialization Stage (6 - 12 weeks) 25 Juvenile Socialization Stage (12 weeks- 6 months) 26 Adolescent Stage (6 months and up) 26 ON HIS OWN FEET 27 Going home with the new owner 27 His New Home 27 The First Night 27 Other Pets 27 Crate Training 28 HOUSE TRAINING 29 Nighttime 29 Submissive Elimination 29 And last but not least . 29 Puppy Manual ASA - 2 - TRAINING YOUR PUP 30 Puppy Learning 30 Reward and Discipline 30 Stealing or Chewing Objects 31 Playing 31 Walking on a Loose Lead 31 Learning to be Alone 32 Car Travel 32 Begging for Food 32 DOGS AND CHILDREN 33 Babies 33 Toddlers between 2 and 6 years old 33 Children between the ages of 6 and12 34 Children older than 12 34 ACTIVITIES WITH YOUR STABYHOUN 35 Obedience Training 35 Agility 35 Barn Hunt 35 Competitive Obedience/Rally-Obedience 35 Canine Musical Freestyle/Rally-FrEe 36 Hunting, Field Trials, and Hunt Tests 36 Fly ball 37 Scent Work 37 Tracking 37 BREEDING 38 FCI BREED STANDARD FOR STABYHOUN 39-44 Puppy Manual ASA - 3 - Congratulations! The Board of the Ameri-Can Stabyhoun Association (ASA) congratulates you on your new puppy. -

Belgian Shepherd and Dutch Shepherd

Belgian Shepherd and Dutch Shepherd HISTORY AND CURRENT TOPICS Jean-Marie Vanbutsele Belgian Dogs Publications BELGIUM Copyright © 2017 by Jean-Marie Vanbutsele. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, dis- tributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photo- copying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, with- out the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non- commercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. Belgian Dogs Publications Donkereham 27 1880 Kapelle-op-den-Bos, Belgium www.belgiandogs.be Book layout and translation: Pascale Vanbutsele Cover image: Dutch Shepherds Aloha kãkou Lani Lotje and Aloha kãkou Riek Wai-Kìkì, photo by Iris Wyss, Switzerland Belgian Shepherd and Dutch Shepherd/ Jean-Marie Vanbutsele —1st ed. Legal deposit: D/2017/9.508/2 ISBN 978-9-0827532-1-9 BISAC: PET008000 PETS / Reference Contents The Belgian Shepherd, History and Current Topics .....................1 The death of Adolphe Reul ...................................................................... 1 The origins of the Belgian Shepherd Dog.............................................. 7 ‘White’ in the Groenendaels .................................................................55 The brindle Belgian Shepherds .............................................................58 Judgements and statements from the Huyghebaert brothers ..........62 -

(FCI) Standard

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) SECRETARIAT GENERAL: 13, Place Albert 1er B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique) ______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ 19.04.2002/ EN _______________________________________________________________ FCI-Standard N° 15 CHIEN DE BERGER BELGE (Belgian Shepherd Dog) 2 TRANSLATION: Mrs. Jeans-Brown, revised by Dr. R. Pollet. Official language (FR). ORIGIN: Belgium. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF OFFICIAL VALID STANDARD: 13.03.2001. UTILISATION: Originally a sheep dog, today a working dog (guarding, defence, tracking, etc.) and an all-purpose service dog, as well as a family dog. FCI-CLASSIFICATION: Group 1 Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle dogs). Section 1 Sheepdogs. With working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY: In Belgium, at the end of the 1800s, there were a great many herding dogs, whose type was varied and whose coats were extremely dissimilar. In order to rationalise this state of affairs, some enthusiastic dog fanciers formed a group and sought guidance from Prof. A. Reul of the Cureghem Veterinary Medical School, whom one must consider to have been the real pioneer and founder of the breed. The breed was officially born between 1891 and 1897. On September 29th, 1891, the Belgian Shepherd Dog Club (Club du Chien de Berger Belge) was founded in Brussels and in the same year on November 15th in Cureghem, Professor A. Reul organised a gathering of 117 dogs, which allowed him to carry out a return and choose the best specimens. In the following years they began a real programme of selection, carrying out some very close interbreeding involving a few stud dogs. By April 3rd, 1892, a first detailed breed standard had already been drawn up by the Belgian Shepherd Dog Club. -

Border Collie) – Germany

Heelwork to Music (Saturday) 1. Monika Gehrke & Nice of you to Come Bye Gigolo Jan (Border Collie) – Germany 2. Sabine Astrom & Promotion Buell Cyclone (Australian Kelpie) – Sweden 3. Marina Stilkenboom & Johnny the Little Black Devil (Schipperke) – Germany 4. Anne Gry Øyeflaten & Havrevingens Ambra (Dutch shepherd) – Norway 5. Minna Yrjana & Like a Hurricane Branwenn Brady (Belgian Shepherd, Malinois) – Finland 6. Anja Jakob & Dancing little Shadow of Fast Crazy Fly (Border Collie) – Germany 7. Olga Kuzina & Almond Chokolat S Chernoy Vody (Australian Shepherd) – Russia 8. Helle Larssen & Littlethorn Avensis (Border Collie) – Denmark 9. Susann Wastenson & Skogvallarens Frodo (Border Collie) – Sweden 10. Carina Persson & Obetes Pop (Border Collie) – Sweden 11. Susanna Ekblom & Cabaroo Dances on Ice (Border Collie) – Finland 12. Lisa Joachimsky & Foxita (Parson Russel terrier) – Germany 13. Kath Hardman & Stillmoor Lady in Red (Border Collie) – Great Britain SHORT BREAK (15 MINUTES) 14. Šimona Drábková & Frederica Alary Aslar (Dobermann) – Czech Republic 15. Christiane Hanchir & Funnyluna van Natterekja (Australian Shepherd) – Belgium 16. Jackie de Jong & Jackie’s Indi (Border Collie) – Great Britain 17. Galina Chogovadze & Sun Light Spot (Border Collie) – Russia 18. Marina Delsink & Gwydion van de Hoge Laer (Belgian Shepherd, Tervueren) – Holland 19. Brigitte van Gestel & Joyful Life van Benvenida’s Joy (Border Collie) – Holland 20. Daniela Šišková & Aurora Piranha Rainy Love (Border Collie) – Czech Republic 21. Anja Christiansen & Feahunden’s Queeny Las (Border Collie) – Denmark 22. Katharina von Dach & Pyla (Border Collie) – Switzerland 23. Monika Olšovská & Arsinoé z Ríše Wa (Border Collie) – Slovakia 24. Sofie Greven & Detania Herfst Roos (Border Collie) – Holland 25. Dylan Smith & Correidhu Chase (Border Collie) – Great Britain 26. -

2012 Annual Report 4 Fédération Cynologique Internationale TABLE of CONTENTS

2012 Annual report 4 Fédération Cynologique Internationale TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of conTenTs I. Message from the President 4 II. Mission Statement 6 III. The General Committee 8 IV. FCI staff 10 V. Executive Director’s report 11 VI. Outstanding Conformation Dogs of the Year 16 VII. Our commissions 19 VIII. FCI Financial report 44 IX. Figures and charts 50 X. 2013 events 59 XI. List of members 67 XII. List of clubs with an FCI contract 75 2012 Annual report 5 MessagE From ThE PrESident Chapter I Message froM The PresidenT be expected on this occasion. Although the World Dog Shows normally take place over four days, the Austrians ventured to hold the event over just 3 days. This meant a considerable increase in the daily number of competitors, which resulted in various difficulties. Experts had reckoned with more than 20,000 dogs taking part in the WDS 2012, so there was some surprise and disappointment when, with a figure of 18,608 dogs, this magic number was not reached. Looking at the causes, it is evident that the shortfall was mainly among those breeds that are still predominantly docked/ cropped in Eastern Europe, but were not admitted in Salzburg. The Austrian Kennel Club succeeded in organising and running this big event with flying colours and without any major hitches. The club and all the officials involved deserve our thanks and recognition for this performance. In appreciation of this and on behalf of the entire team, Dr Michael Kreiner, President of the Austrian Kennel Club, and Ms Margrit Brenner, the WDS Director, were awarded a badge of honour by the FCI. -

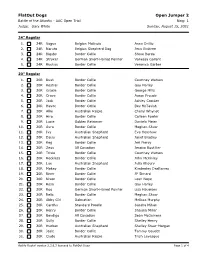

Flatout Dogs Open Jumper 2 Battle of the Atlantic - AAC Open Trial Ring: 1 Judge: Gary White Sunday, August 15, 2021

FlatOut Dogs Open Jumper 2 Battle of the Atlantic - AAC Open Trial Ring: 1 Judge: Gary White Sunday, August 15, 2021 24" Regular 1. 24R Vogue Belgian Malinois Anne Drillio 2. 24R Naruto Belgian Shepherd Dog Jenn Embree 3. 24R Bigsby Border Collie Steve Borda 4. 24R Stryker German Short-Haired Pointer Vanessa Gallant 5. 24R Ruckus Border Collie Veronica Garber 20" Regular 1. 20R Rush Border Collie Courtney Watson 2. 20R Kestrel Border Collie Gay Harley 3. 20R Gracie Border Collie George Mills 4. 20R Crave Border Collie Aaron Froude 5. 20R Jack Border Collie Ashley Crocker 6. 20R Havoc Border Collie Bev McTavish 7. 20R Allie Australian Kelpie Cheryl Whynot 8. 20R Hiro Border Collie Colleen Fowler 9. 20R Lucie Golden Retriever Daniela Meier 10. 20R Aura Border Collie Meghan Shaw 11. 20R Ivy Australian Shepherd Eva Henshaw 12. 20R Daisy Australian Shepherd Janet Bradley 13. 20R Keg Border Collie Jeri Piercy 14. 20R Zeus All Canadian Jessica Boutilier 15. 20R Trixie Border Collie Courtney Watson 16. 20R Reckless Border Collie John McKinley 17. 20R Lux Australian Shepherd Julia Khoury 18. 20R Mokey Border Collie Kimberley DesBarres 19. 20R River Border Collie JP Simard 20. 20R Nixon Border Collie Leah Noye 21. 20R Rosa Border Collie Gay Harley 22. 20R Roo German Short-Haired Pointer Lisa Haueisen 23. 20R Relic Border Collie Meghan Shaw 24. 20R Abby Girl Dalmatian Melissa Murphy 25. 20R Cardhu Standard Poodle Sandra Mihan 26. 20R Henry Border Collie Shauna Miller 27. 20R Bendigo All Canadian Sean McGuiness 28. 20R Sully Border Collie Shelley Henry 29. -

Annual Report 2 Table of Contents

2016 Annual report 2 Table of contents Table of contents I. Message from the President 3 II. Mission Statement 4 III. The General Committee 6 IV. FCI staff 8 V. Executive Director’s report 9 VI. Outstanding Conformation Dogs of the Year 12 VII. Our commissions 15 VIII. Financial report 39 IX. Figures 42 X. 2017 events 53 XI. List of members 61 XII. List of clubs with an FCI contract 70 Fédération Cynologique Internationale Chapter I Message from the President 3 Message from the President about the weakness of the FCI, today we are more united than ever, with new countries joining and the commitment of Australia and New Zealand to remain as part of the FCI. We are also in continuous communication with organisations such as the American Kennel Club, the Canadian Kennel Club and the UK Kennel Club to promote responsible dog breeding, promote the recognition of pedigrees and judges, and the joint effort to preserve dog sports and responsible breeding around the world. We are renewing our administrative capacities, with new processing and data entry equipment to better serve our members. We are also repeating our communications efforts inserting the FCI in international campaigns on dog’s welfare with the purpose of creating dog-loving societies in every corner on Earth. We are rethinking how we communicate with the younger generations of dog lovers with the creation of study manuals on dog sports and dog activities for every Another year has concluded and like any other year we are age while promoting the inclusion of younger individuals celebrating our success and learning from our members. -

Origin and History of the Belgian Shepherd

HUNDRED YEARS OF HISTORY OF THE BELGIAN SHEPHERD DOG MALINOIS LAEKEN GROENENDAEL TERVUEREN ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF THE VARIETIES OF THE BELGIAN SHEPHERD DOG [CANIS LUPUS PECARIUS BELGICUS] Jean-Marie VANBUTSELE translated by Pascale Vanbutsele, 1988 Copyright 1989 by Jean-Marie VANBUTSELE. All rights reserved worldwide. No part of this document may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, transcribed or translated into any language without the prior permission of the author. ii to G L A D Y my faithful Malinois ALSH No 33186 "When you have lived with a "Belgian," you will understand better the passion for animals." "The fidelity of a dog is a precious gift, that involves moral commitment which is not less binding than the friendship of a human fellow" Konrad LORENZ iii CONTENTS I THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DOG 1 II FROM THE DEFENCE TO THE GUIDANCE OF SHEEP 5 IIII THE ORIGIN OF THE BREED THE BLUEPRINT BY PROFESSOR A.REUL 9 IV THE WINDS OF DISCORD 15 V THE SHORT-HAIRED 22 VI THE ROUGH-HAIRED AMONG WHICH THE LAEKEN 31 VII THE LONG-HAIRED 35 VIII BETWEEN THE TWO WORLD WARS 42 IX FROM 1946 UNTIL THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY (1991) 47 X FEATURES AND EVALUATION 54 THE FIRST STANDARD OF THE BREED APRIL 1892 58 CURRENT STANDARD 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY 63 iv One should remember that the union of man with dog, together with the usage of fire, are the most important events in the history of civilization. Let us have a look at what A. TOUSSENEL wrote in his book « L'Esprit des betes » ( 1862 ): "It is the dog that has made the human society from a disordered into a patriarchal state, by giving man the flock. -

Evaluering FCI

Evaluering FCI Med bakgrunn i vedtak i RS 2014 - sak 5d, RS 2015 - sak 5 samt HS sak 131/15, 106/16 og 113/16 Notatet er utarbeidet av NKKs administrasjon og behandlet av Hovedstyret i sak 131/15, 106/16 og 113/15. Notatet er vedtatt publisert i uke 37/2016. 1 DEL A Utvikling vedr. FCI og Kina-saken siden september 2015 Bakgrunn for – og hensikt med dette dokument: Representantskapsmøtet 2014 ga NKKs Hovedstyre følgende oppdrag: Utrede fordeler og ulemper med medlemskap i FCI. Utredningen skal redegjøre for hvilke tiltak som kan iverksettes for å heve NKKs kompetanse knyttet til FCI, hvorledes NKK kan utøve demokratiske rettigheter som medlem og hvordan man evt. kan bøte på de ulemper som i dag finnes knyttet til FCI medlemskapet. Notatet «Hovedstyrets handlingsplan – Evaluering av FCI» – ble utarbeidet og lagt frem på Hovedstyremøte 9/15, sak nr 131. HS besluttet da at det utarbeidede notatet ikke skulle sendes ut med sakspapirene til RS 2015 pga de forhandlingssituasjonene NKK og andre nordiske kennelklubber på det tidspunktet var inne i. Hovedpunktene ble derfor lagt frem muntlig på RS 2015. Representantskapsmøtet ga sin tilslutning til dette. Forslagsstiller bak vedtak fattet på Representantskapsmøtet 2014, Fuglehundklubbenes Forbund, bekreftet da også at de ikke så behov for at denne evalueringen ble lagt frem. Representantskapsmøtet 2015 ga Hovedstyret deretter oppdraget: NKKs erfaring med og evaluering av FCI skal gi grunnlag for Hovedstyrets behandling og oppfølging av NKKs medlemskap i FCI. Hovedstyret gis fullmakt til å endre NKKs medlemskap i FCI, alternativt å begjære uttreden. NKK avventer å søke internasjonale show for 2018. -

ACT Companion Dog Club 26Th March 2016

ACT Companion Dog Club 26th March 2016 Master Agility Judge: Ms Helen Mosslar (ACT) SCT: 51 sec 2 1st 200 AgCh Flutterwing Zoro Zen ADM8 JDM11 SPDM SDM GDX JDO ADO (Papillon) Stacy Richards 39.38s 1st 300 Charlie JDX ADX GD SD SPD (Associate) Heather Addie 44.18s 2nd 300 Tess RN ADM6 ADO6 JDM5 JDO4 GDM SDM SPDM (Associate) Joyce Clark 45.67s 3rd 300 Pepe CCD ADM3 ADO3 JDX JDO GDX SDX SPD (Associate) Mrs Nga Bustamante 49.98s 1st 500 AgCh 500 Kerodan Hidden Colours RN ADM JDM ADO JDO GDM SDM SPDM (Border Collie) Miss Sarah Kirkwood 33.78s 2nd 500 Ohutu Jett (imp Nzl) RA ADM ADO JDM JDO GDX SDX SPDX HTMS (Border Collie) Nicole Keller 37.46s 3rd 500 AgCh 500 Dazzle UD RE ADM JDM ADO JDO GDM SDM SPDX (Australian Kelpie) Barbara Brown 40.90s 4th 500 Borderart Choc Teddy ADX JDX GD SPD (Border Collie) Louise Meagher 42.27s 1st 600 Beljekali Yoda ADM JDM GDX SDX SPDX (Belgian Shepherd Dog (Tervueren)) Paul Enriquez 35.37s Excellent Agility Judge: Ms Helen Mosslar (ACT) SCT: 55 sec 3 1st 200 Ch Walampton Piccolo Fortissimo AD JDX SPDX SD GD (Jack Russell Terrier) Mrs D Gowans 36.67s 1st 500 Cliffhanger Quinn (imp Nzl) AD JD GD (Border Collie) Miss Michelle Tunbridge 27.55s 2nd 500 Borderart Savoir Faire CDX JD SPD AD GD (Border Collie) Judy Roger 28.98s 1st 600 Brunig AD JDX GD SPD (Associate) Linda Spinaze 33.65s Novice Agility Judge: Ms Helen Mosslar (ACT) SCT: 52 sec 4 1st 500 Bailey RN (Associate Register) Carla Sexton 27.50s 2nd 500 Dart (Associate) Heather Addie 32.14s 3rd 500 Kerodan Triplechoc Surprise JD (Border Collie) Amanda Delaney -

Annual Report

International Partnership for Dogs ANNUAL 2019 REPORT A Growing Voice A LOT TO CELEBRATE AND GREAT POTENTIAL ON WHICH TO CAPITALIZE 2 2019 IPFD Annual Report | DogWellNet.com CONTENTS 04 05 06 From the CEO From the Chair Our Mission, Vision, Values, and Goals 08 12 14 Who We Are/What We Do Our Board and Officers Our Consultants 16 18 20 Our Contributors DogWellNet.com Harmonization of Genetic Testing for Dogs 22 24 26 IPFD International Dog Administration Into the Future Health Workshops 2019 IPFD Annual Report | DogWellNet.com 3 From the CEO In our fifth full year of operation, we made significant strides in several key initiatives, and 2020 promises to be a pivotal year for IPFD. As a start-up non-profit five years ago, we represented a good idea with an admirable mission. Many of our supporters were enthusiastic about the concept, but perhaps unclear about the details of what could be accomplished. IPFD has developed based on a strategy of ‘if we build it, they will come’. The progress has been gratifying, and the achievements remarkable. The acknowledgement of the need for multi-stakeholder, international collaboration and action is widespread and consistent. In addition, the impartial, balanced, big-picture, and inclusive approach of IPFD has led to the recognition of how important it is to have such a voice speaking on the complex challenges of dog health and welfare. However, the realities of the dog world and the demands of local, regional, and national responsibilities of our volunteers and collaborators means that there is increased demand on IPFD, not only to be the integrating hub for resources, but also for us to provide more person-power to make this happen. -

Dog Breeds Volume 5

Dog Breeds - Volume 5 A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Russell Terrier 1 1.1 History ................................................. 1 1.1.1 Breed development in England and Australia ........................ 1 1.1.2 The Russell Terrier in the U.S.A. .............................. 2 1.1.3 More ............................................. 2 1.2 References ............................................... 2 1.3 External links ............................................. 3 2 Saarloos wolfdog 4 2.1 History ................................................. 4 2.2 Size and appearance .......................................... 4 2.3 See also ................................................ 4 2.4 References ............................................... 4 2.5 External links ............................................. 4 3 Sabueso Español 5 3.1 History ................................................ 5 3.2 Appearance .............................................. 5 3.3 Use .................................................. 7 3.4 Fictional Spanish Hounds ....................................... 8 3.5 References .............................................. 8 3.6 External links ............................................. 8 4 Saint-Usuge Spaniel 9 4.1 History ................................................. 9 4.2 Description .............................................. 9 4.2.1 Temperament ......................................... 10 4.3 References ............................................... 10 4.4 External links