Applicability of Intrinsic Value Models at the Segmented Chinese Stock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016Semi-Annual Report

CHINA CONVERGENCE FUND A Sub-fund of Value Partners Intelligent Funds SEMI-ANNUAL 2016 REPORT For the six months ended 30 June 2016 Value Partners Limited 9th Floor, Nexxus Building 41 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong Tel: (852) 2880 9263 Fax: (852) 2565 7975 Email: [email protected] Website: www.valuepartners-group.com In the event of inconsistency, the English text of this Semi-Annual Report shall prevail over the Chinese text. This report shall not constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy shares in any of the funds. Subscriptions are to be made only on the basis of the information contained in the explanatory memorandum, as supplemented by the latest semi-annual and annual reports. CHINA CONVERGENCE FUND A Sub-fund of Value Partners Intelligent Funds (A Cayman Islands unit trust) CONTENTS Pages General information 2-3 Manager’s report 4-9 Statement of financial position (unaudited) 10 Investment portfolio (unaudited) 11-15 Investment portfolio movements (unaudited) 16 SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT 2016 For the six months ended 30 June 2016 1 CHINA CONVERGENCE FUND A Sub-fund of Value Partners Intelligent Funds (A Cayman Islands unit trust) GENERAL INFORMATION Manager Legal Advisors Value Partners Limited With respect to Cayman Islands law 9th Floor, Nexxus Building Maples and Calder 41 Connaught Road Central 53rd Floor, The Center Hong Kong 99 Queen’s Road Central Hong Kong Directors of the Manager Dato’ Seri Cheah Cheng Hye With respect to Hong Kong law Mr. Ho Man Kei, Norman King & Wood Mallesons Mr. So Chun Ki Louis 13th Floor, Gloucester Tower The Landmark Trustee, Registrar, Administrator and 15 Queen’s Road Central Principal Office Hong Kong Bank of Bermuda (Cayman) Limited P.O. -

Conference Review 21-22.9.2017 | Ramada Plaza Shunde Host:

3rd Edition CPRJ Plastics in Appliance/3C Electronics Conference & Showcase Conference Review 21-22.9.2017 | Ramada Plaza Shunde Host: Adsale Publishing Ltd. Organizer: China Plastic & Rubber Journal Co-organizers: Midea Group, Shunde Home Appliance Chamber of Shenzhen Electronic Chamber of Commerce Commerce Industrial Design Society of Shunde Guangdong Plastics Industry Association Industrial and Daily-use Electrical Appliance Institute of China Electrical Equipment Industrial Association Guangdong Electronics CMF Design Organization and Information Industries Association Supporters: CHINAPLAS Society of Plastic Engineers SpecialChem.com Federation of Hong Kong Industries Media Partner: More details:AdsaleCPRJ.com/3CConference 1 / 16 3rd Edition CPRJ Plastics in Appliance/3C Electronics Conference & Showcase Salute to the following sponsors VIP Sponsors: Diamond Sponsors: Exhibitors: Other Sponsors: 2 / 16 Programme 21 September Morning Session 08:00-12:00 08:00 Audience Reception 08:50 Welcome Remarks Adsale Group - Stanley Chu,Chairman Industrial and Daily-use Electrical Appliance Institute of China Electrical Equipment Industrial Association - Yiqi Xu,Secretary General 09:00 China Household Electrical Appliance Association - Xiaohong Hu,Senior Engineer The Moderator: Dr.Xiong Yuming Development trends of Chinese home appliances industry and plastic application Senior Material 09:30 Midea Group - Shuyang Qin,Plastics Technology Management Director,Purchasing Center Research Engineer Discussion on innovations of plastics for smart home appliances of Academia Sinica Midea Group 10:00 Jinyoung (Xiamen) Advanced Materials Technology Co.,Ltd. - Keanu,Sales Director Meeting new trends? We already have your solutions.-- Special material solutions of Jinyoung help you meet the new requirements of home consumer applicable industry 10:05 Coffee Break / Networking / Exhibition Visiting 10:35 Lenovo (Shenzhen) Electronic Co.,Ltd. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK BYD COMPANY LTD., Plaintiff, V. VICE MEDIA LLC Defendant. Case No. C

Case 1:20-cv-03281 Document 1 Filed 04/27/20 Page 1 of 81 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK BYD COMPANY LTD., Case No. Plaintiff, COMPLAINT v. JURY TRIAL DEMANDED VICE MEDIA LLC Defendant. Plaintiff BYD Company Ltd. (“BYD”) alleges: SUMMARY OF THE CASE 1. This is an action for defamation against VICE Media, which published at least two grossly defamatory statements of and concerning BYD that have caused substantial harm. 2. BYD (an acronym for “Build Your Dreams”), is a publicly-traded corporation based in China. BYD is one of the world’s largest producers and suppliers of electric vehicles including electric cars, buses, trucks and forklifts, as well as solar panels, lithium batteries, and protective masks and equipment, among many other innovative, important and useful products. Warren Buffet’s company, Berkshire Hathaway, is a major investor in BYD. BYD recently won a contract to supply the State of California with $1 billion worth of masks to protect its nurses, doctors, caregivers, first responders and other frontline personnel during and after the COVID-19 global pandemic. 3. Before the events that gave rise to this litigation, BYD enjoyed a very good reputation as a reliable supplier of quality products in the global marketplace. {00108017;3} Case 1:20-cv-03281 Document 1 Filed 04/27/20 Page 2 of 81 4. On or about April 11, 2020, VICE Media published an article on its website at vice.com (the “Article”) falsely claiming that BYD was implicated in one of the most publicized and brutal human rights violations of modern times, the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uyghur minority in Eastern China. -

Major Chinese Industrial Companies

AllChinaReports.com Industry Reports, Company Reports & Industry Analysis Directory: Major Chinese Industrial Companies ● 186 Industries ● 1435 Top Companies ● 999 Company Websites Beijing Zeefer Consulting Ltd. April 2012 Disclaimer Authorized by: Beijing Zeefer Consulting Ltd. Company Site: http://www.Zeefer.org Online Store of China Industry Reports: http://www.AllChinaReports.com Beijing Zeefer Consulting Ltd. and (or) its affiliates (hereafter, "Zeefer") provide this document with the greatest possible care. Nevertheless, Zeefer makes no guarantee whatsoever regarding the accuracy, utility, or certainty of the information in this document. Further, Zeefer disclaims any and all responsibility for damages that may result from the use or non-use of the information in this document. The information in this document may be incomplete and/or may differ in expression from other information in elsewhere by other means. The information contained in this document may also be changed or removed without prior notice. Table of Contents CIC Code Industry Page 0610 Coal Mining 1 0620 Lignite Mining 2 0690 Other Coal Mining 3 0710 Crude Petroleum & Natural Gas Extraction 3 0810 Iron Ores Mining 5 1320 Feed Processing 6 1331 Edible Vegetable Oil Processing 7 1332 Inedible Vegetable Oil Processing 8 1340 Sugar Mfg. 9 1351 Livestock & Poultry Slaughtering 10 1352 Meat Processing 11 1361 Frozen Aquatic Products Processing 12 1411 Pastry & Bread Mfg. 13 1419 Biscuit & Other Baked Foods Mfg. 14 1421 Candy & Chocolate Mfg. 16 1422 Preserved Fruits Mfg. 17 1431 Rice & Flour Products Mfg. 18 1432 Quick Frozen Foods Mfg. 19 1439 Instant Noodle & Other Convenient Foods Mfg. 21 1440 Liquid Dairy & Dairy Products Mfg. -

Holding of Equities at 31 December 2010 Oting Oting S Ector M Arket Value ( NO K) V O Wnership S Ector M Arket Value ( NO K) V O Wnership

Government Pension Fund Global Holding of equities at 31 December 2010 K) K) arket value arket value wnership wnership ector ector oting oting no no s m ( v o s m ( v o ANTigUA ANd BARBUdA Duet Group Financials 67 801 033 0.76% 0.76% sinovac biotech ltd Health Care 17 397 650 1.22% 1.22% DuluxGroup ltd industrials 14 035 765 0.23% 0.23% ARgENTiNA eastern star Gas ltd oil & Gas 15 972 052 0.33% 0.33% Cresud saCiF y a Consumer Goods 16 548 188 0.00% 0.30% elders ltd Consumer Goods 8 543 687 0.55% 0.55% AUsTRALiA emeco Holdings ltd industrials 17 287 528 0.43% 0.43% abacus Property Group Financials 18 476 197 0.36% 0.36% energy Developments ltd utilities 626 541 0.03% 0.02% adelaide brighton ltd industrials 196 794 506 1.58% 1.58% energy resources of australia ltd Basic materials 9 135 640 0.07% 0.07% aeD oil ltd oil & Gas 1 835 871 0.38% 0.38% energy World Corp ltd utilities 10 185 047 0.19% 0.19% aGl energy ltd utilities 150 436 589 0.36% 0.36% envestra ltd utilities 16 409 659 0.37% 0.37% aJ lucas Group ltd industrials 3 989 731 0.42% 0.42% extract resources ltd basic materials 5 770 933 0.04% 0.04% alesco Corp ltd industrials 7 773 325 0.52% 0.52% Fairfax media ltd Consumer services 90 860 701 0.46% 0.46% alliance resources ltd basic materials 1 989 515 0.19% 0.19% FKP Property Group Financials 22 518 477 0.38% 0.38% alumina ltd basic materials 324 993 536 0.90% 0.90% Fleetwood Corp ltd Consumer Goods 23 729 853 0.54% 0.54% amcor ltd/australia industrials 243 166 314 0.49% 0.49% Flight Centre ltd Consumer services 52 328 985 0.36% 0.36% -

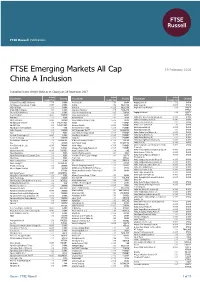

FTSE Emerging Markets All Cap China a Inclusion

FTSE Russell Publications FTSE Emerging Markets All Cap 19 February 2018 China A Inclusion Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 29 December 2017 Index Index Index Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country weight (%) weight (%) weight (%) 21Vianet Group (ADS) (N Shares) 0.01 CHINA Air China (H) 0.04 CHINA Angang Steel (H) 0.02 CHINA 361 Degrees International (P Chip) <0.005 CHINA AirAsia 0.02 MALAYSIA Angel Yeast (A) <0.005 CHINA 3SBio (P Chip) 0.04 CHINA AirAsia X <0.005 MALAYSIA Anglo American Platinum 0.03 SOUTH 51job ADR (N Shares) 0.01 CHINA Airports of Thailand 0.17 THAILAND AFRICA 58.com ADS (N Shares) 0.06 CHINA Airtac International Group 0.05 TAIWAN Anglogold Ashanti 0.08 SOUTH A.G.V. Products <0.005 TAIWAN Aisino Corporation (A) 0.01 CHINA AFRICA ABB India 0.02 INDIA Ajanta Pharma 0.01 INDIA Anhui Anke Biotechnology (Group) (A) <0.005 CHINA Ability Enterprise <0.005 TAIWAN Ajisen China Holdings (P Chip) <0.005 CHINA Anhui Chaodong Cement (A) <0.005 CHINA Aboitiz Equity Ventures 0.06 PHILIPPINES Akbank 0.1 TURKEY Anhui Conch Cement (A) 0.02 CHINA Aboitiz Power 0.02 PHILIPPINES Akcansa Cimento <0.005 TURKEY Anhui Conch Cement (H) 0.1 CHINA Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank 0.07 UAE Akenerji Elektrik Uretim <0.005 TURKEY Anhui Expressway (A) <0.005 CHINA AcBel Polytech 0.01 TAIWAN AKR Corporindo Tbk PT 0.01 INDONESIA Anhui Expressway (H) 0.01 CHINA ACC 0.02 INDIA Aksa Akrilik Ve Kimya Sanayii <0.005 TURKEY Anhui Golden Seed Winery (A) <0.005 CHINA Accelink Technologies (A) <0.005 CHINA Aksa Enerji Uretim AS <0.005 TURKEY Anhui Gujing Distillery (A) <0.005 CHINA Accton Technology 0.03 TAIWAN Aksigorta <0.005 TURKEY Anhui Gujing Distillery (B) 0.01 CHINA Ace Hardware Indonesia 0.01 INDONESIA Al Meera Consumer Goods Co. -

U.S. Capital Markets Footprint of Chinese Companies Sanctioned for XUAR Human Rights Violations

U.S. Capital Markets Footprint of Chinese Companies Sanctioned for XUAR Human Rights Violations September 18, 2020 The U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) has added several dozen Chinese companies to the Entity List for “acting contrary to the foreign policy interests of the United States” and, more specifically, having been implicated in human rights violations and the implementation of mass arbitrary detention, high-technology and biometric surveillance, and forced labor against Uyghurs in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) since the fall of 2019. This follows over three decades of sweeping security measures and assimilationist policies enacted by the Chinese government, aimed at repressing Uyghur religious belief and practice, and marginalizing Uyghur ethnic identity and culture. On July 22, 2020, the Commerce Department added eleven Chinese companies to the Entity List “in connection with the practice of forced labor involving Uyghurs and other Muslim minority groups” and “conducting genetic analyses used to further the repression of Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities” in the XUAR.1 On May 22, 2020, the Commerce Department added eight Chinese companies and institutions to the Entity List for being “complicit in human rights violations and abuses,” mass arbitrary detention, and high-tech surveillance in the XUAR:2 On October 9, 2019, the Commerce Department added 28 entities, including eight Chinese companies. to the Entity List for having been “implicated in human rights violations and abuses,” -

Between Catch-Up and Engagement in Emerging Technologies Marina Oulion

The acquisition of technological capabilities by large Chinese industrial companies : between catch-up and engagement in emerging technologies Marina Oulion To cite this version: Marina Oulion. The acquisition of technological capabilities by large Chinese industrial companies : between catch-up and engagement in emerging technologies. Economics and Finance. Université Paris-Est, 2016. English. NNT : 2016PESC0114. tel-01483966v2 HAL Id: tel-01483966 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01483966v2 Submitted on 8 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE PARIS-EST ECOLE DOCTORALE ORGANISATIONS, MARCHES, INSTITUTIONS Thèse de doctorat en Sciences de Gestion Menée au Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire Sciences Innovations Sociétés (LISIS) d’Université Paris-Est Soutenue par Marina OULION le 12 décembre 2016 L’ACQUISITION DE COMPÉTENCES TECHNOLOGIQUES PAR LES GRANDES ENTREPRISES INDUSTRIELLES CHINOISES. Entre rattrapage et investissement des technologies émergentes Thèse dirigée par LARÉDO Philippe, professeur, UPEM et Université -

Case 1:20-Cv-03281-AJN Document 1 Filed 04/27/20 Page 1 of 81

Case 1:20-cv-03281-AJN Document 1 Filed 04/27/20 Page 1 of 81 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK BYD COMPANY LTD., Case No. Plaintiff, COMPLAINT v. JURY TRIAL DEMANDED VICE MEDIA LLC Defendant. Plaintiff BYD Company Ltd. (“BYD”) alleges: SUMMARY OF THE CASE 1. This is an action for defamation against VICE Media, which published at least two grossly defamatory statements of and concerning BYD that have caused substantial harm. 2. BYD (an acronym for “Build Your Dreams”), is a publicly-traded corporation based in China. BYD is one of the world’s largest producers and suppliers of electric vehicles including electric cars, buses, trucks and forklifts, as well as solar panels, lithium batteries, and protective masks and equipment, among many other innovative, important and useful products. Warren Buffet’s company, Berkshire Hathaway, is a major investor in BYD. BYD recently won a contract to supply the State of California with $1 billion worth of masks to protect its nurses, doctors, caregivers, first responders and other frontline personnel during and after the COVID-19 global pandemic. 3. Before the events that gave rise to this litigation, BYD enjoyed a very good reputation as a reliable supplier of quality products in the global marketplace. {00108017;3} Case 1:20-cv-03281-AJN Document 1 Filed 04/27/20 Page 2 of 81 4. On or about April 11, 2020, VICE Media published an article on its website at vice.com (the “Article”) falsely claiming that BYD was implicated in one of the most publicized and brutal human rights violations of modern times, the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uyghur minority in Eastern China. -

Vanguard Emerging Markets Stock Index Fund Annual Report October

Annual Report | October 31, 2016 Vanguard Emerging Markets Stock Index Fund A new format, unwavering commitment As you begin reading this report, you’ll notice that we’ve made some improvements to the opening sections—based on feedback from you, our clients. Page 1 starts with a new ”Your Fund’s Performance at a Glance,” a concise, handy summary of how your fund performed during the period. In the renamed ”Chairman’s Perspective,” Bill McNabb will focus on enduring principles and investment insights. We’ve modified some tables, and eliminated some redundancy, but we haven’t removed any information. At Vanguard, we’re always looking for better ways to communicate and to help you make sound investment decisions. Thank you for entrusting your assets to us. Contents Your Fund’s Performance at a Glance. 1 Chairman’s Perspective. 3 Fund Profile. .7 Performance Summary. .9 Financial Statements. 12 Your Fund’s After-Tax Returns. 37 About Your Fund’s Expenses. 38 Glossary. 40 Please note: The opinions expressed in this report are just that—informed opinions. They should not be considered promises or advice. Also, please keep in mind that the information and opinions cover the period through the date on the front of this report. Of course, the risks of investing in your fund are spelled out in the prospectus. See the Glossary for definitions of investment terms used in this report. About the cover: No matter what language you speak, Vanguard has one consistent message and set of principles. Our primary focus is on you, our clients. We conduct our business with integrity as a faithful steward of your assets. -

CHN 18/2020 12 March 2021

PALAIS DES NATIONS • 1211 GENEVA 10, SWITZERLAND Mandates of the Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises; the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights; the Special Rapporteur on minority issues; the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief; the Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, including its causes and consequences; the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; and the Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, especially women and children REFERENCE: AL CHN 18/2020 12 March 2021 Excellency, We have the honour to address you in our capacities as Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises; Working Group on Arbitrary Detention; Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights; Special Rapporteur on minority issues; Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief; Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, including its causes and consequences; Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; and Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons, especially women and children, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 44/15, 42/22, 37/12, 43/8, 40/10, 42/10, 43/20 and 44/4. In this connection, we would like to bring to the attention of your Excellency’s Government information we have received concerning the alleged forced labour, arbitrary detention, and trafficking in persons of Uyghur and other minority workers within and outside the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang), as well as the related lack of accountability and access to effective remedy for victims. -

2020 Year in Review

CHAPTER 2 U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND TRADE RELATIONS SECTION 1: YEAR IN REVIEW: ECONOMICS AND TRADE Key Findings • China’s gross domestic product (GDP) contracted 6.8 percent the first quarter of 2020, marking the worst quarterly performance since 1992 and the first contraction since the Mao era. Respond- ing to the economic shock, China’s government reverted to past practices, exacerbating enduring structural problems within China’s economy. Massive state-led investment and other policy choices have benefitted state-owned enterprises (SOEs) at the expense of households and small business and risk increasing global overcapacity, inequality, and debt buildup. • U.S.-China tensions continued to escalate over trade and nation- al security concerns. The U.S. Department of Commerce tight- ened restrictions on Huawei and added over 100 China-based entries to the Entity List for a range of activities, including illic- itly providing U.S. technology to China’s military, aiding in the repression of China’s ethnic Uyghur minority, and constructing artificial islands in the South China Sea. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security also blocked Chinese imports from facto- ries and companies suspected of using forced labor, primarily in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Chinese leaders have threatened retaliatory treatment and redoubled efforts to secure technological self-sufficiency. • Continuing trade tensions and shortages related to the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic revealed key supply chain vulnerabilities, prompting the United States and its allies to accelerate their reassessment of dependence on Chi- na for critical inputs and finished goods. As 2020 comes to a close, U.S.