Studies in Dyirbal, Yidifl, and Warrgamay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University Final Report Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale, Melissa George, Rosemary Hill and Duane Fraser Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale1, Melissa George2, Rosemary Hill3 and Duane Fraser 1The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns 2NAILSMA, Darwin 3CSIRO, Cairns Supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme Project 3.9: Indigenous capacity building and increased participation in management of Queensland sea country © CSIRO, 2016 Creative Commons Attribution Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? is licensed by CSIRO for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: 978-1-925088-91-5 This report should be cited as: Dale, A., George, M., Hill, R. and Fraser, D. (2016) Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?. Report to the National Environmental Science Programme. Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (50pp.). Published by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre on behalf of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme (NESP) Tropical Water Quality (TWQ) Hub. The Tropical Water Quality Hub is part of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme and is administered by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

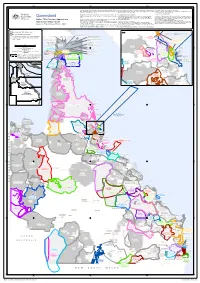

Northern Queensland Region Topographic Vector Data Is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience the Register of Native Title Claims (RNTC), If a Registered Application

142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E 150°0'E Hopevale Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from external boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of Currency is based on the information as held by the NNTT and may not NNTT based on data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © areas being claimed) as they have been recognised by the Federal reflect all decisions of the Federal Court. The State of Queensland for that portion where their data has been Court process. To determine whether any areas fall within the external boundary of an used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal application or determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and Court, the map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per databases is required. Further information is available from the QUD673/2014 Northern Queensland Region Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience the Register of Native Title Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. Tribunals website at www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Cape York United Number 1 Claim Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 (QC2014/008) Non freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members March 2021. registration test), and agents and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) Native Title Claimant Applications and - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being accept no liability and give no undertakings guarantees or warranties KOWANYAMA COO KTOW N (! (! As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in applied, concerning the accuracy, completeness or fitness for purpose of the Determination Areas 1998, all applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal - unregistered applications (i.e. -

A Study Guide by Emily Dawson

© ATOM 2016 A STUDY GUIDE BY EMILY DAWSON http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-940-5 http://theeducationshop.com.au CONTENTS 1 Indigenous Perspectives 2 Synopsis 3 The importance of language and the need for more projects like Yamani: Voices of an Ancient Land 4 Yamani Artist profiles: language and knowledge holders Music available at: https://wantokmusik.bandcamp.com/albumyamani-voices-of-an-ancient-land a Accompanied by brief introductions to Gunggari, Video available at: https://vimeo.com/140554259 Butchulla, Kalaw Kawaw Ya, Yugambeh and Warrgamay languages INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVES 5 Queensland Indigenous Languages Advisory This study guide has been written for those Committee committed teachers upholding their responsibility to teach for reconciliation through the use of quality 6 Wantok Musik Fountation of Indigenous content and committed intercultural and cross-cultural pedagogy. 7 National Professional Standards for Teachers, The Melbourne Declaration of Educational Goals National professional standards and curriculum for Young Australians, The UN Declaration on the documents (outlined below) mandate that all Rights of Indigenous Peoples teachers are to teach, and therefore all students 8 Direct curriculum links between Yamani: Voices of across all year levels are to be taught, an an Ancient Land and the Australian Curriculum by Indigenous curriculum. However, it is noted that Primary level. Suggested student activities include: these documents do not provide specific outcomes for teachers and students. As teachers experience a Language and singing Country immense time constraints and often low levels of practical and meaningful intercultural education, b Alternative perspectives and alternate texts the scaffolding aim of these curriculum documents can be lost as teachers juggle the various content c Song/text response they must cover. -

See Also Kriol

Index A 125, 127, 133–34, 138, 140, 158–59, 162–66, 168, 171, 193, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander 214, 218, 265, 283, 429. Commission (ATSIC) 107, 403, case studies 158 405 Dharug 182, 186–87 Training Policy Statement 2004–06 Miriwoong 149 170 Ngarrindjeri 396 Aboriginal Education Consultative Group Wergaia 247 (AECG) xiii, xviii, 69, 178, 195, Wiradjuri 159, 214, 216–18, 222–23 205 adverbs 333, 409, 411 Dubbo 222 Alphabetic principle 283–84 Aboriginal Education Officers (AEOs) Anaiwan (language) 171 189, 200, 211, 257 Certificate I qualification 171 Aboriginal English xix, 6, 9, 15–16, 76, Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara 91, 147, 293, 303, 364, 373, 383. (APY) 86. See also Pitjantjatjara See also Kriol (language) Aboriginal Land Rights [Northern Territory] Arabana (language) 30 Act 228, 367 language program 30 Aboriginal Languages of Victoria Re- See source Portal (ALV-RP) 310, 315, archival records. language source 317, 320 materials portal architecture 317–319 Arrernte (language) 84–85 Victorian Word Finder 316 Arwarbukarl Cultural Resource Associa- See also Aboriginal Languages Summer School tion (ACRA) 359. Miro- 108, 218 maa Language Program Aboriginal Resource Development Ser- Aboriginal training agency 359 vices (ARDS) xxix workshops 359 absolutive case 379 Audacity sound editing software 334, accusative case 379 393 adjectives audio recordings 29–30, 32, 56, 94, 96, Gamilaraay 409, 411 104, 109–11, 115–16, 121, 123– Ngemba 46 26, 128, 148, 175, 243–44, 309, Wiradjuri 333 316, 327–28, 331–32, 334–35, Yuwaalaraay 411 340, 353, 357–59, 368, 375, 388, See also Adnyamathanha (language) 57 403, 405, 408, 422. -

MUSE Issue 24, October 2019

Art. Culture. Issue 24 Antiquities. October 2019 Natural history. Until next time A word from the Director, David Ellis This is the last issue of Muse before We are fortunate to have benefited the Nicholson closes on 28 February from the extraordinary generosity 2020. We hope you will be able to of Neville Grace, whose bequest of join us for a number of public events 62 Australian impressionist paintings between then and now, including a have made a transformative impact closing party hosted by the Friends on the collection, many of which you of the Nicholson in February. Muse will be able to see in the opening suite Victorian era’s equivalent to lunar will take a break during an intensive of exhibitions. exploration, and its 1874 visit to period of exhibition development Sydney. Then there is the surprising until the next issue in May 2020, at As a harbinger of our new museum, interplay between big data and which time we will share up-to-the- this issue of Muse draws together small insects. minute details on the Chau Chak other insights from across the Wing Museum as it heads towards complexity of our collections. The During our consultation with opening. The September issue will latest in medical imaging technology Girringun artists we witness the commemorate the much-anticipated continues to expose secrets from strengthening connections to the opening in August. our antiquities collection, including past that are revitalising traditional the revelation that parsimonious artefact- and art-making practices, This issue brings us up to date ancient Greeks valued their olive oil and we observe insights into our with our regular feature on the too highly to commit unnecessarily European art via the Bauhaus as museum site. -

Monitoring Indigenous Heritage Within the Reef 2050 Integrated

© Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Institute of Marine Science) 2019 Published by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority ISBN 978-0-6485892-0-4 This document is licensed for use under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logos of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and the Queensland Government, any other material protected by a trademark, content supplied by third parties and any photographs. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc/4.0/ A catalogue record for this publication is available from the National Library of Australia. This publication should be cited as: Jarvis, D., Hill, R., Buissereth, R., Moran, C., Talbot, L.D., Bullio, R., Grant, C., Dale, A., Deshong, S., Fraser, D., Gooch, M., Hale, L., Mann, M., Singleton, G. and Wren, L., 2019, Monitoring the Indigenous heritage within the Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program: Final Report of the Indigenous Heritage Expert Group, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville. Front cover image: Aerial drone image of Sawmill Beach, Whitsundays. © Commonwealth of Australia (GBRMPA), Photographer: Andrew Denzin. DISCLAIMER While reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth of Australia, represented by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court. -

A Linguistic Bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands

OZBIB: a linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands Dedicated to speakers of the languages of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands and al/ who work to preserve these languages Carrington, L. and Triffitt, G. OZBIB: A linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. D-92, x + 292 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-D92.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian NatIonal University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. -

Female Invisibility in the Male's World of Plantation-Era Tropical North

Female Invisibility in the Male’s World of Plantation-Era Tropical North Queensland Bianka Vidonja Balanzategui James Cook University Abstract Australian rural history accounts abound with the admirable, foolhardy and often savage exploits of white male protagonists, while women, white or of colour, are generally invisible. This is despite the fact there is a substantial primary record of the history of European settlement in rural Australia. Taking the Herbert River Valley, located in tropical north Queensland, as a case study, this article fleshes out the scant detail of the women who, alongside the men, battled life on the frontier of European incursion into Indigenous Country. It will focus on the experiences of three women: Manbarra woman Jenny, Melanesian indentured labourer Annie Etinside, and Australian-born Chinese woman Eliza Jane Ah Bow, and how their lives were enmeshed with those of white women who lived alongside them in the Herbert River Valley in the late nineteenth century. These women were hardly bystanders and observers but active participants in the drama of colonisation that melded cultures from across the globe. Women lived in the Herbert River Valley, in the north Kennedy district of tropical north Queensland, from the beginning of European incursion in the area in the late nineteenth century.1 Among them was Manbarra woman Jenny, Australian-born Chinese woman Eliza Jane Ah Bow and Melanesian indentured labourer Annie Etinside, as well as white women Isabella Mackenzie, Isabella Campbell, Elizabeth Burrows and Louisa Buchanan. Such women have often been invisible in the historical record as European men, who penned the majority of this history, did not see women beyond their domestic arrangements. -

Arthur Capell Papers MS 4577 Finding Aid Prepared by J.E

Arthur Capell papers MS 4577 Finding aid prepared by J.E. Churches, additional material added by C. Zdanowicz This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit May 04, 2016 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library March 2010 1 Lawson Crescent Acton Peninsula Acton Canberra, ACT, 2600 +61 2 6246 1111 [email protected] Arthur Capell papers MS 4577 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................. 4 Biographical note ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Scope and Contents note ............................................................................................................................... 6 Arrangement note .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Administrative Information ......................................................................................................................... 8 Related Materials ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings ......................................................................................................................... 9 Physical Characteristics