Repor T Resumes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Person Meets Word Part 1: Personalism in the Language

WTJ 77 (2015): 355–77 WHERE PERSON MEETS WORD PART 1: PERSONALISM IN THE LANGUAGE THEORY OF KENNETH L. PIKE Pierce Taylor Hibbs I. Introduction eformed theology has always championed the Trinity as the beating heart of the Christian faith. This is true not just of the mainstay his- torical Reformers, Luther and Calvin, but also of Dutch Calvinism, Old R 1 Princeton, and the Westminster heritage. Certainly, Calvin and Melanchthon were not alone in claiming that “God’s triunity was that which distinguished the true and living God from idols.”2 The true God is the Trinity. Out of this tradition emerged Cornelius Van Til and his insistence that the self-contained ontological Trinity be the basis of all human experience and knowledge.3 He claimed that “if we are to have coherence in our experience, Pierce Hibbs currently serves as the Assistant Director of the Center for Theological Writing at Westminster Theological Seminary. 1 On Luther, see David Lumpp, “Returning to Wittenberg: What Martin Luther Teaches Today’s Theologians on the Holy Trinity,” CTQ 67 (2003): 232, 233–34; and Mickey Mattox, “From Faith to the Text and Back Again: Martin Luther on the Trinity in the Old Testament,” ProEccl 15 (2006): 292. On Calvin, see T. F. Torrance, “Calvin’s Doctrine of the Trinity,” CTJ 25 (1990): 166. For an example of the Dutch Calvinist view, see Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, ed. John Bolt, trans. John Vriend, 4 vols. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003–2008), 2:279, 329. For Old Princeton, see Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2013), 1:442; and B. -

Éducation Et Didactique, 5-3 | 2011 a Curious Mixture of Passion and Reserve”: Understanding the Etic/Emic Distin

Éducation et didactique 5-3 | 2011 Varia A Curious Mixture of Passion and Reserve”: Understanding the Etic/Emic Distinction Christina Hahn, Jane Jorgenson and Wendy Leeds-Hurwitz Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/educationdidactique/1167 DOI: 10.4000/educationdidactique.1167 ISSN: 2111-4838 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 30 December 2011 Number of pages: 145-154 ISBN: 978-2-7535-1832-2 ISSN: 1956-3485 Electronic reference Christina Hahn, Jane Jorgenson and Wendy Leeds-Hurwitz, « A Curious Mixture of Passion and Reserve”: Understanding the Etic/Emic Distinction », Éducation et didactique [Online], 5-3 | 2011, Online since 30 December 2013, connection on 09 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ educationdidactique/1167 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/educationdidactique.1167 This text was automatically generated on 9 December 2020. Tous droits réservés A Curious Mixture of Passion and Reserve”: Understanding the Etic/Emic Distin... 1 A Curious Mixture of Passion and Reserve”: Understanding the Etic/ Emic Distinction Christina Hahn, Jane Jorgenson and Wendy Leeds-Hurwitz 1 The title of this chapter alludes to the complex requirements placed on ethnographic researchers who maintain multiple roles as both insiders and outsiders to the social settings they study. When in the role of insiders, researchers try to apprehend the contextualized meanings of people’s experiences within specific locales, while in their role as outsiders, they seek to identify commonalities across different locales. Clyde Kluckhohn alluded to this tension when he proposed that « the hallmark of the good anthropologist must be a curious mixture of passion and reserve » (1957, pp. -

Language Revitalization As Rebuilding a Speech Community

Language Revitalization as Rebuilding a Speech Community MARIANNA DI PAOLO, LISA JOHNSON, SARAH ARNOFF, JENNIFER MITCHELL, DERRON BORDERS ICLDC- 4 HONOLULU, HI FEBRUARY 28, 2015 Wick R. Miller Collection Shoshoni Language Project, Who we are University of Utah Project began in 2002 Focus--to preserve and disseminate Miller’s collection NSF: #0418351, PI: M.J. Mixco, Co-PI: M. Di Paolo. 2004-2007. In 2007, focus shifted to revitalization Barrick Gold of North America Inc. PI: Marianna Di Paolo. 2007-2014. Shoshoni Language: Past & Future Uto- Wick Miller predicted that Aztecan Shoshoni would probably be gone by the late 20th century Northern Uto- Aztecan Few children were using it in the home by the late 1960’s Numic US Census estimate 2006- 2010 Central 2,211 Shoshoni speakers Numic 1,319 living in tribal communities Timbisha Shoshoni Comanche Shoshone/Goshute Communities What is a speech community? “A linguistic community is a social group which may be either From an anthropologist (Gumperz 1972:463) monolingual or multilingual, held together by frequency of social interaction patterns and set off from the surrounding areas by weaknesses in the lines of communication.” (Emphasis is ours.) What is a speech community? “The speech community is not defined From a sociolinguist by any marked agreement in the use of (Labov 1972:120) language elements, so much as by participation in a set of shared norms; these norms may be observed in overt types of evaluative behavior, and by the uniformity of abstract patterns of variation which are invariant in respect to particular levels of usage.” (Emphasis is ours.) What is a speech community? Themes Frequent interactions by members of the community using the language variety in question Shared language norms among community members, which influence their linguistic behavior People who derive a sense of identity from the community and together constitute the community Why do Languages don’t die out because of a languages die? lack of dictionaries, or grammars, or classes, or recordings. -

Conference on American Indian Languages Clearinghouse Newsletter

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 100 146 FL 006 141 AUTHOR Fidelholtz, James L., Ed. TITLE Conference on American Indian Languages Clearinghouse Newsletter. Vol. 2, No. 1. PUB DATE Jun 73 NOTE 21p.; Filmed from best available copy EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; *American Indian Languages; Bibliographies; *Bilingual Education; Bilingualism; Language Instruction; Linguistics; *Newsletters; Second Language Learning ABSTRACT The first report in this issue, from Fort McPherson, MVT, concerns the ongoing work of transcribing, recording, and teaching Kutchin. In addition, there are reports concerning efforts in progress to preserve various Indian languages, among them Kwakiutl, Skagit, Shulkayn, Shoshoni, and Ojibway. Other investigations and courses in Alaskan native languagesare also mentioned. The status of the Tehlequah bilingual Cherokeeprogram is briefly reported, and the Navajo community-controlled bilingual program in Rough Rock, Arizona is described. A list of GPO publications involving Indian languages is provided, as is an annotated list of books available from other sources. Excerpts from the 'General Discussion of Papers by Mattingly and Halle' from 'Language by Ear and by Eye,' edited by James Kavanaugh and Ignatious Mattingly, are also provided. (LG) AMMO 110111more IggIgg% CONFERENCEL ON 1MERICAM INDIAN LANnUAGES CLEARINGHOUSEIMETTER =EN ..r...410.01arret. .1,1110.1 maw 1DIVIR: JAMES L.FIDELHOLTZ VOLVIE II,NO, 1 .1 WE, 173 PArE . U S DEPARTMENTOF HEALTH. NEADTUICOANTAILON HA,;. BEEN REPRO c DOCUMENT C f ROM 44S TWI TEuLTFEAR0EF xA( Tt Y AS GENE 1 DU( D oRIGIN EDUCATION tosoN ORGANIZATION THE Of, OPINiON Af,NC.ITpOiNTS Of VtF ALEXANDRA :"'AUSS MEMORIAL FUND ,.,4YED DO NOI NE( f. -

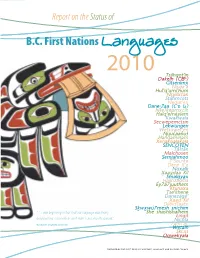

2010 Report on the Status of B.C First Nations Languages

Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages 2010 Tsilhqot’in Dakelh (ᑕᗸᒡ) Gitsenimx̱ Nisg̱a’a Hul’q’umi’num Nsyilxcən St̓át̓imcets Nedut’en Dane-Zaa (ᑕᓀ ᖚ) Nłeʔkepmxcín Halq’eméylem Kwak̓wala Secwepemctsin Lekwungen Wetsuwet’en Nuučaan̓uɫ Hən̓q̓əm̓inəm̓ enaksialak̓ala SENĆOŦEN Tāłtān Malchosen Semiahmoo T’Sou-ke Dene K’e Nuxalk X̱aaydaa Kil Sm̓algya̱x Hailhzaqvla Éy7á7juuthem Ktunaxa Tse’khene Danezāgé’ X̱aad Kil Diitiidʔaatx̣ Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim “…I was beginning to fear that our language was slowly She shashishalhem Łingít disappearing, especially as each Elder is put into the ground.” Nicola Clara Camille, secwepemctsin speaker Pəntl’áč Wetalh Ski:xs Oowekyala prepared by the First peoples’ heritage, language and Culture CounCil The First Peoples’ Heritage, Language and Culture Council (First We sincerely thank the B.C. First Nations language revitalization Peoples’ Council) is a provincial Crown Corporation dedicated to First experts for the expertise and input they provided. Nations languages, arts and culture. Since its formation in 1990, the Dr. Lorna Williams First Peoples’ Council has distributed over $21.5 million to communi- Mandy Na’zinek Jimmie, M.A. ties to fund arts, language and culture projects. Maxine Baptiste, M.A. Dr. Ewa Czaykowski-Higgins The Board and Advisory Committee of the First Peoples’ Council consist of First Nations community representatives from across B.C. We are grateful to the three language communities featured in our case studies that provided us with information on the exceptional The First Peoples’ Council Mandate, as laid out in the First Peoples’ language revitalization work they are doing. Council Act, is to: Nuučaan̓uɫ (Barclay Dialect) • Preserve, restore and enhance First Nations’ heritage, language Halq’emeylem (Upriver Halkomelem) and culture. -

Handbook-Of-Semiotics.Pdf

Page i Handbook of Semiotics Page ii Advances in Semiotics THOMAS A. SEBEOK, GENERAL EDITOR Page iii Handbook of Semiotics Winfried Nöth Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis Page iv First Paperback Edition 1995 This Englishlanguage edition is the enlarged and completely revised version of a work by Winfried Nöth originally published as Handbuch der Semiotik in 1985 by J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart. ©1990 by Winfried Nöth All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Nöth, Winfried. [Handbuch der Semiotik. English] Handbook of semiotics / Winfried Nöth. p. cm.—(Advances in semiotics) Enlarged translation of: Handbuch der Semiotik. Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. ISBN 0253341205 1. Semiotics—handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Communication —Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title. II. Series. P99.N6513 1990 302.2—dc20 8945199 ISBN 0253209595 (pbk.) CIP 4 5 6 00 99 98 Page v CONTENTS Preface ix Introduction 3 I. History and Classics of Modern Semiotics History of Semiotics 11 Peirce 39 Morris 48 Saussure 56 Hjelmslev 64 Jakobson 74 II. Sign and Meaning Sign 79 Meaning, Sense, and Reference 92 Semantics and Semiotics 103 Typology of Signs: Sign, Signal, Index 107 Symbol 115 Icon and Iconicity 121 Metaphor 128 Information 134 Page vi III. -

Angol-Magyar Nyelvészeti Szakszótár

PORKOLÁB - FEKETE ANGOL- MAGYAR NYELVÉSZETI SZAKSZÓTÁR SZERZŐI KIADÁS, PÉCS 2021 Porkoláb Ádám - Fekete Tamás Angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótár Szerzői kiadás Pécs, 2021 Összeállították, szerkesztették és tördelték: Porkoláb Ádám Fekete Tamás Borítóterv: Porkoláb Ádám A tördelés LaTeX rendszer szerint, az Overleaf online tördelőrendszerével készült. A felhasznált sablon Vel ([email protected]) munkája. https://www.latextemplates.com/template/dictionary A szótárhoz nyújtott segítő szándékú megjegyzéseket, hibajelentéseket, javaslatokat, illetve felajánlásokat a szótár hagyományos, nyomdai úton történő előállítására vonatkozóan az [email protected] illetve a [email protected] e-mail címekre várjuk. Köszönjük szépen! 1. kiadás Szerzői, elektronikus kiadás ISBN 978-615-01-1075-2 El˝oszóaz els˝okiadáshoz Üdvözöljük az Olvasót! Magyar nyelven már az érdekl˝od˝oközönség hozzáférhet német–magyar, orosz–magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárakhoz, ám a modern id˝ok tudományos világnyelvéhez, az angolhoz még nem készült nyelvészeti célú szak- szótár. Ennek a több évtizedes hiánynak a leküzdésére vállalkoztunk. A nyelvtudo- mány rohamos fejl˝odéseés differenciálódása tovább sürgette, hogy elkészítsük az els˝omagyar-angol és angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárakat. Jelen kötetben a kétnyelv˝unyelvészeti szakszótárunk angol-magyar részét veheti kezébe az Olvasó. Tervünk azonban nem el˝odöknélküli vállalkozás: tudomásunk szerint két nyelvészeti csoport kísérelt meg a miénkhez hasonló angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárat létrehozni. Az els˝opróbálkozás -

Gaelic Nova Scotia an Economic, Cultural, and Social Impact Study

Curatorial Report No. 97 GAELIC NOVA SCOTIA AN ECONOMIC, CULTURAL, AND SOCIAL IMPACT STUDY Michael Kennedy 1 Nova Scotia Museum Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada November 2002 Maps of Nova Scotia GAELIC NOVA SCOTIA AN ECONOMIC, CULTURAL, AND SOCIAL IMPACT STUDY Michael Kennedy Nova Scotia Museum Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada Nova Scotia Museum 1747 Summer Street Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3A6 © Crown copyright, Province of Nova Scotia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing from the Nova Scotia Museum, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Nova Scotia Museum at the above address. Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0-88871-774-1 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Section One: The Marginalization of Gaelic Celtic Roots 10 Gaelic Settlement of Nova Scotia 16 Gaelic Nova Scotia 21 The Status of Gaelic in the 19th Century 27 The Thin Edge of The Wedge: Education in 19th-Century Nova Scotia 39 Gaelic Language and Status: The 20th Century 63 The Multicultural Era: New Initiatives, Old Problems 91 The Current Status of Gaelic in Nova Scotia 112 Section Two: Gaelic Culture in Nova Scotia The Social Environment 115 Cultural Expression 128 Gaelic and the Modern Media 222 Gaelic Organizations 230 Section Three: Culture and Tourism The Community Approach 236 The Institutional Approach 237 Cultural Promotion 244 Section Four: The Gaelic Economy Events 261 Lessons 271 Products 272 Recording 273 Touring 273 Section Five: Looking Ahead Strengths of Gaelic Nova Scotia 275 Weaknesses 280 Opportunities 285 Threats 290 Priorities 295 Bibliography Selected Bibliography 318 INTRODUCTION Scope and Method Scottish Gaels are one of Nova Scotia’s largest ethnic groups, and Gaelic culture contributes tens of millions of dollars per year to the provincial economy. -

Theme and the Function of the Verb in Palestinian Arabic Narrative Discourse

THEME AND THE FUNCTION OF THE VERB IN PALESTINIAN ARABIC NARRATIVE DISCOURSE BY ILHAM NAYEF ABU-GHAZALEH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1983 , To my sister SHADYIA, who refused to continue her studies at Cairo University after the final occupation of Palestine in 1967 - She said, before she was killed at the age of -nineteen "WHAT IS THE USE OF A UNIVERSITY DEGREE FOR A PALESTINIAN WHEN HE HAS NO WALL TO HANG IT ON?" . ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thankfulness to the head of my committee, Dr. Chauncey Chu, is limitless. I am greatly indebted to him for his tireless devotion and generosity in giving of his valuable time to crystallize this work. His kind and patient encourage- ment has been an important factor in my academic growth. My gratitude also goes to the rest of the members of my committee. Dr. Alice Faber's comments, guidance and sup- port sharpened my perception in this analysis. Dr. Bill Sullivan enriched my analysis by helping me see other sides to it. Dr. Robert de Beaugrande always enabled me to put things into perspective through his discussions, concern and encouragement. My discussions with Dr. Rene LeMarchand were of great importance to me. My greatest thanks and love go to my home university, Birzeit, for providing me with this opportunity for growth and enrichment. The difficulties they were enduring while I was far from them constituted a heavy part of my personal suffering To all my friends in Gainesville, in the United States, and at home, go my unlimited love and gratitude. -

Daly Berman 1 Amanda Elaine Daly Berman Boston University, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Musicology And

Daly Berman 1 Amanda Elaine Daly Berman Boston University, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Musicology and Ethnomusicology Repression to Reification: Remembering and Revitalizing the Cape Breton Musical Diaspora in the Celtic Commonwealth INTRODUCTION Cape Breton Island, the northeast island of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, has long had a strong connection with New England, and the Boston area in particular, due to its maritime location and relative geographic proximity. At its peak in the mid-20th century, the Boston Cape Breton community is estimated to have numbered close to 100,000 members. However, as Sean Smith writes in the June 3, 2010 issue of the Boston Irish Reporter, Greater Boston’s Cape Breton community is undergoing a transition, with the graying of the generation that played such a major role during the 1950s and 1960s in establishing this area as a legendary outpost for music and dance of the Canadian Maritimes. Subsequent generations of Cape Bretoners have simply not come down to the so-called “Boston states” on the same scale, according to the elders; what’s more, they add, the overall commitment to traditional music and dance hasn’t been as strong as in past generations.1 Further, he notes that it is “non-Cape Bretoners [e.g., members of other Maritime communities, non-Cape Breton Bostonians] who seem to make up more of the attendance at these monthly dances” held at the Canadian-American Club (also known as the Cape Breton Gaelic Club) in Watertown, Massachusetts. The club serves as a gathering site for area members of the Cape Breton and the greater Maritime diaspora, offering a monthly Cape Breton Gaelic Club Ceilidh and weekly Maritime open mic sessions. -

Region and the Rise of Neoliberalism in the Fiction of Alistair Macleod

A Family of Migrant Workers: Region and the Rise of Neoliberalism in the Fiction of Alistair MacLeod Jody Mason he values accorded to labour in Canadian literary dis- courses have shifted remarkably since the early nineteenth cen- tury, when a literary culture in English was first nurtured by Tanglophone settlers. Oliver Goldsmith’s frequently anthologized long poem “The Rising Village” (1825) presents the figure of the individual male labourer (in this case, a farmer) as one who performs his territor- ial claim via his improvement of the soil. By cultivating the land, this labourer is able to repulse the omnipresent threat of the “wandering Indian”: “By patient firmness and industrious toil / He still retains pos- session of the soil” (lines 103-04). This essentially Lockean argument — that the individual ownership of goods and property is justified by the labour exerted to produce those goods — is frequently repeated in Canadian literary discourses (in some prairie novels of the modern period, for example) and often serves nation-making ends (when it is harnessed to Romantic nationalism in the Confederation period, for example). Of course, this argument depends on labour that is under- taken in a specific place. However, writers in Canada have long called attention to the fact that Canada is a place shaped by another kind of labour practice — labour that is mobile, that migrates, that does not stay in place. Contemporary novels such as Michael Ondaatje’s In the Skin of a Lion (1987), Cecil Foster’s Slammin’ Tar (1998), Alistair MacLeod’s No Great Mischief (1999), and, more recently, Robert McGill’s Once We Had a Country (2013) all direct readers to an alternative conception of labour’s place in Canadian cultural history, urging us to see that the settler claims forged through labour (and the improvement of land) elide alternative histories of work and class relations. -

In Memoriam Zdeněk F. Oliverius

Specimina Philologiae Slavicae ∙ Supplementband 15 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Jonathan E. M. Clarke (Hrsg.) In memoriam Zdeněk F. Oliverius Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbHJonathan. E. M. Clarke - 978-3-95479-515-4 Downloaded from PubFactory at 09/23/2021 05:42:51PM via free access 00047499 Jonathan E. M. Clarke - 978-3-95479-515-4 Downloaded from PubFactory at 09/23/2021 05:42:51PM via free access 00047499 SPECIMINA PHILOLOGIAE SLAVICAE Herausgegeben von Olexa Horbatsch und Gerd Freidhof Supplementband 15 IN MEMORIAM ZDENÈK F. OLIVERIUS J. MARVAN - S.B.VLADIV ־ J.E.M. CLARKE (EDITORS) VERLAG OTTO SAGNER • MÜNCHEN 1985 Jonathan E. M. Clarke - 978-3-95479-515-4 Downloaded from PubFactory at 09/23/2021 05:42:51PM via free access This volume is dedicated to the memory of Zdenëk F. Oliverius, one of the pioneers in the field of Russian studies in Australia, who died in Prague in 1978. It has been published with the assistance of the Monash University Publications Committee. ISBN 3-87690-306-8 Copyright by Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1985. Abteilung der Firma Kubon und Sagner, München. Druck: Görich & Weiershäuser, 3550 Marburg/L. Bayerische Staatebibliothek München Jonathan E.