Alcohol Consumption and Risk for Parkinson's Disease: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Membership Recognition

Membership Recognition AIST takes this opportunity to recognize our members for their years of loyalty and ongoing commitment to the iron and steel industry. Each year, AIST publishes a roster of individuals reaching significant anniversaries of membership, beginning with 10 years and continuing with each successive five-year anniversary. AIST Members Celebrating an Anniversary in 2014 50+ Consecutive Years of Membership Jagdish C. Agarwal Lowell L. French Otto J. Leone Jr. Walter D. Sadowski L. James Anderson Gordon H. Geiger Edward C. Levy Jr. Norman L. Samways Shank R. Balajee Carl E. Glaser Timothy Lewis S.D. Sanders John A. Beatrice Henry G. Goehring Louis W. Lherbier Nobuo Sano Joel Gary Bernstein Thomas C. Graham Claude H.P. Lupis Edward J. Schaming William H. Betts James F. Hamilton Raymond M. Mader Winfried F. Schmiedberg Kenneth E. Blazek Narwani Harman Alexander McLean William A. Schmucker David T. Blazevic Roger Heaton Akgun Mertdogan Herbert D. Sellers Sr. Gary L. Bowman John D. Heffernan Royston P. Morgan Sudhir K. Sharma John C. Campbell Harry O. Hefter Paul R. Morrow Bruce M. Shields Richard J. Choulet Wallace L. Hick Jr. John M. Negomir Charles E. Slater Thomas A. Cleary Jr. Edwin M. Horak Sanford M. Nobel Ralph M. Smailer C. Larry Coe Tobin Humphrey John C. Pearl Russell Solomon III Denis L. Creazzi George A. Jedenoff K.G. Pedersen George R. St. Pierre Charles Criss John E. Jetkiewicz Robert D. Pehlke Barry A. Strathdee Roy L. Cross Behram M. Kapadia Raymond L. Polick Joseph M. Strouse Jr. James F. Cunningham Clifford W. Kehr K. -

Language Models As Knowledge Bases: on Entity Representations, Storage Capacity, and Paraphrased Queries

Language Models as Knowledge Bases: On Entity Representations, Storage Capacity, and Paraphrased Queries Benjamin Heinzerling1, 2 and Kentaro Inui2, 1 1RIKEN AIP & 2Tohoku University [email protected] j [email protected] Abstract Pretrained language models have been sug- gested as a possible alternative or comple- ment to structured knowledge bases. However, this emerging LM-as-KB paradigm has so far only been considered in a very limited setting, which only allows handling 21k entities whose Figure 1: The LM-as-KB paradigm, introduced by name is found in common LM vocabularies. Petroni et al.(2019). A LM memorizes factual state- Furthermore, a major benefit of this paradigm, ments, which can be queried in natural language. i.e., querying the KB using natural language paraphrases, is underexplored. Here we formu- However, this emerging LM-as-KB paradigm is late two basic requirements for treating LMs as KBs: (i) the ability to store a large num- faced with several foundational questions. ber facts involving a large number of entities First question: KBs contain millions of entities, and (ii) the ability to query stored facts. We while LM vocabulary size usually does not exceed explore three entity representations that allow 100k entries. How can millions of entities be rep- LMs to handle millions of entities and present resented in LMs? Petroni et al.(2019) circum- a detailed case study on paraphrased querying vent this problem by only considering 21k enti- of facts stored in LMs, thereby providing a ties whose canonical name corresponds to a single proof-of-concept that language models can in- deed serve as knowledge bases. -

Post-Translational Modification of MRE11: Its Implication in DDR And

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Post-Translational Modification of MRE11: Its Implication in DDR and Diseases Ruiqing Lu 1,† , Han Zhang 2,† , Yi-Nan Jiang 1, Zhao-Qi Wang 3,4, Litao Sun 5,* and Zhong-Wei Zhou 1,* 1 School of Medicine, Sun Yat-Sen University, Shenzhen 518107, China; [email protected] (R.L.); [email protected] (Y.-N.J.) 2 Institute of Medical Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College; Kunming 650118, China; [email protected] 3 Leibniz Institute on Aging–Fritz Lipmann Institute (FLI), 07745 Jena, Germany; zhao-qi.wang@leibniz-fli.de 4 Faculty of Biological Sciences, Friedrich-Schiller-University of Jena, 07745 Jena, Germany 5 School of Public Health (Shenzhen), Sun Yat-Sen University, Shenzhen 518107, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (Z.-W.Z.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Maintaining genomic stability is vital for cells as well as individual organisms. The meiotic recombination-related gene MRE11 (meiotic recombination 11) is essential for preserving genomic stability through its important roles in the resection of broken DNA ends, DNA damage response (DDR), DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) repair, and telomere maintenance. The post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and methylation, regulate directly the function of MRE11 and endow MRE11 with capabilities to respond to cellular processes in promptly, precisely, and with more diversified manners. Here in this paper, we focus primarily on the PTMs of MRE11 and their roles in DNA response and repair, maintenance of genomic stability, as well as their Citation: Lu, R.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, association with diseases such as cancer. -

Colorectal Cancer SCHWEIZER Dezember 2013 04

Dezember 2013 04 Erscheint vierteljährlich Jahrgang 33 DU CANCER SCHWEIZER KREBSBULLETIN BULLETIN SUISSE Via Ernährung das Darmkrebsrisiko senken, S. 337 Schwerpunkt: Colorectal Cancer BAND 33, DEZEMBER 2013, AUFLAGE 4200 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Editorial KLS Krebsliga Schweiz 334 Würdigung herausragender Verdienste für krebsbetroffene 281-282 After and before WOF Menschen F. Cavalli K. Bodenmüller Pressespiegel 335 Brustzentrum des Kantonsspitals Baden mit Qualitätslabel ausgezeichnet 285-290 Cancer in the media K. Bodenmüller Schwerpunktthema 336 Brustkrebs: Eine Anziehpuppe erleichtert Gespräche Colorectal cancer zwischen Eltern und Kindern S. Jenny 293-295 Colorectal cancer: much has been done, but there is still a long way to go 337 Via Ernährung das Darmkrebsrisiko senken P. Saletti K. Zuk 296-298 Kolonkarzinomscreening 2013: Sind wir einen Schritt 338 Un honneur qui récompense de grands mérites en faveur weiter? des personnes atteintes du cancer U.A. Marbet, P. Bauerfeind K. Bodenmüller 339 Remise du label de qualité au Centre du sein de l’Hôpital 299 Kolorektales Karzinom in der Schweiz cantonal de Baden M. Montemurro K. Bodenmüller 300-301 Kassenpflicht für Kolonkarzinom-Früherkennung 340 Nouvelle formation continue en psycho-oncologie K. Haldemann Interview avec Dr. Friedrich Stiefel V. Moser Celio 302-306 Epidémiologie et prise en charge du cancer colorectal: une étude de population en Valais 342 Fort- und Weiterbildungen der Krebsliga Schweiz I. Konzelmann, S. Anchisi, V. Bettschart, J.-L. Bulliard, Formation continue de la Ligue suisse contre le cancer A. Chiolero OPS Onkologiepflege Schweiz Originalartikel 344-346 Hautveränderungen bei antitumoralen Therapien S. Wiedmer 309-313 Neglected symptoms in palliative cancer care T. Fusi, P. Sanna SGMO Schweizerische Gesellschaft 315-318 Multidisciplinary management of urogenital für Medizinische Onkologie tumours at the Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale 349 Elektronisches Patientendossier und Behandlungspfade E. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Angelo Auricchio, M.D., Ph.D., F.E.S.C PERSONAL Citizenship status Italian Date of birth August 24, 1960 Place of birth Terzigno, Italy Marital status Married, 3 children Mailing address Division of Cardiology Istituto Cardiocentro Ticino Via Tesserete 48 CH-6900 Lugano Switzerland Business Phone + 41 91 805 3879 Fax + 41 91 805 3213 Email [email protected] Languages Italian, English, and German OrcID https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2116-6993 EDUCATION 1979 – 1985 Medical School, Federico II - University of Naples, Italy 1985 – 1989 Specialization in Cardiology, Federico II - University of Naples, 1 Italy 1991 – 1994 Dottorato di Ricerca in Fisiopatologia Cardiovascolare, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy TRAINING Internship 1981 – 1983 Department of Microbiology, University of Naples, Italy 1983 – 1985 Department of Metabolic Diseases, University of Naples, Italy Internal Medicine Resident 1985 – 1986 Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital, Naples, Italy Cardiology Fellow 1986 – 1988 Division of Cardiology, University Hospital, Naples, Italy 1988 – 1991 Division of Cardiology, University Hospital, Hannover, Germany CERTIFICATION 1985 MD – degree, Naples, Italy 1988 Board of Cardiology, Naples, Italy HOSPITAL APPOINTMENTS 1986 – 1988 Assistant Staff Physician, University Hospital, Naples, Italy 1988 – 1991 Assistant Staff Physician, University Hospital, Hannover, Germany 1991 – 1994 Attending Physician, Division of Cardiac Surgery, University Hospital Rome, Italy VI-VIII 1994 Visiting -

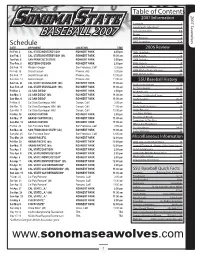

BASEBALL 2007 Roster 5 2007 Preview 6 Schedule 2007 Seawolves 7-14 DATE OPPONENT LOCATION TIME 2006 Review Fri-Feb

Table of Contents 2007 Information 2007 Seawolves Schedule 1 Head Coach John Goelz 2 Assistant Coaches 3-4 BASEBALL 2007 Roster 5 2007 Preview 6 Schedule 2007 Seawolves 7-14 DATE OPPONENT LOCATION TIME 2006 Review Fri-Feb. 2 CAL STATE MONTEREY BAY ROHNERT PARK 2:00 pm 2006 Highlights 16 Sat-Feb. 3 CAL STATE MONTEREY BAY (dh) ROHNERT PARK 11:00 am 2006 Results 16 Tue-Feb. 6 SAN FRANCISCO STATE ROHNERT PARK 2:00 pm 2006 Statistics 17-19 Thu-Feb. 8 WESTERN OREGON ROHNERT PARK 2:00 pm 2006 Honors 19 Sat-Feb. 10 Western Oregon San Francisco, Calif 2:00 pm 2006 CCAA Standings 20 Fri-Feb. 16 Grand Canyon Phoenix, Ariz 5:00 pm 2006 All-Conference Honors 20 2006 CCAA Leaders 21 Sat-Feb. 17 Grand Canyon (dh) Phoenix, Ariz 12:00 pm Sun-Feb. 18 Grand Canyon Phoenix, Ariz 11:00 am SSU Baseball History Sat-Feb. 24 CAL STATE STANISLAUS* (dh) ROHNERT PARK 11:00 am Yearly Team Honors 22 Sun-Feb. 25 CAL STATE STANISLAUS* (dh) ROHNERT PARK 11:00 am All-Time Awards 22-23 Fri-Mar. 2 UC SAN DIEGO* ROHNERT PARK 2:00 pm All-Americans 24 Sat-Mar. 3 UC SAN DIEGO* (dh) ROHNERT PARK 11:00 am All-Time SSU Baseball Team 25 Sun-Mar. 4 UC SAN DIEGO* ROHNERT PARK 11:00 am Yearly Leaders 26-27 Fri-Mar. 9 Cal State Dominguez Hills* Carson, Calif 2:00 pm Records 28-30 Sat-Mar. 10 Cal State Dominguez Hills* (dh) Carson, Calif 11:00 am Yearly Team Statistics 30 Sun-Mar. -

Where Are You Talking About? Advances and Challenges of Geographic Analysis of Text with Application to Disease Monitoring

Where are you talking about? Advances and Challenges of Geographic Analysis of Text with Application to Disease Monitoring Milan Gritta Supervisor: Dr Nigel Collier Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Fitzwilliam College February 2019 Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. Itis not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limitforthe relevant Degree Committee. Milan Gritta February 2019 Where are you talking about? Advances and Challenges of Geographic Analysis of Text with Application to Disease Monitoring Abstract - Milan Gritta The Natural Language Processing task we focus on in this thesis is Geoparsing. Geoparsing is the process of extraction and grounding of toponyms (place names). Consider this sentence: "The victims of the Spanish earthquake off the coast of Malaga were of American and Mexican origin." Four toponyms will be extracted (called Geotagging) and grounded to their geographic coordinates (called Toponym Resolution). -

Search Unclaimed Property

VOL P. 3835 FRIDAY, JUNE 15, 2018 THE LEGAL INTELLIGENCER • 19 SEARCH UNCLAIMED PROPERTY Philadelphia County has unclaimed property waiting to be claimed. For information about the nature and value of the property, or to check for additional names, visit www.patreasury.gov Pennsylvania Treasury Department, 1-800-222-2046. Notice of Names of Persons Appearing to be Owners of Abandoned and Unclaimed Property Philadelphia County Listed in Alphabetical Order by Last Known Reported Zip Code Philadelphia County Southern Bank Emergency Physicians Hyun Heesu Strange Timothy L Caul Almena D Southernmost Emergency Irrevocable Trust of Kathleen Rafferty Stursberg Henry J Cera Robert A Spectrum Emergency Care Ishikawa Masahiro Suadwa Augustine A Chakravarty Rajit 19019 Spiritual Frontiers Fellowship Jack Paller and Company Inc Sulit Jeremy William Chang Dustin W Buck Mary Stantec Consulting Services Jacob I Hubbart Pennwin Clothes Corp Sullivan Thomas J Chao Shelah Burlington Anesthesia Assoc Su Ling Jaffe Hough Taylor Ronald Charlotte Field Davis Catherine C Taylor Kyle W W Jain Monica Thales Avionics Inc Chca Inc Oncology Decicco Mary Tchefuncta Emerg Phys Jdjs Inc The Sun Coast Trade Exchange Checker Cab Company Inc Dittus Betty Teleflex Automotive Group Jeffrey R Lessin Associates The Vesper Club Chen Kesi Grzybows Kathryn Texas Emi Medical Services Jeffrey Reiff Trust Thompson Howard Chen Roberta Hawley Philip E Thompson Barbara Johnson Jerry A Thompson Kathleen M Chernukhina Evgeniya A Huber Catherine L Thompson Marjorie Jones Chanie B Thurlow -

PHYSICS PUBLICATIONS JLAB NUMBER TITLE of PAPER AUTHOR(S) Published? Year Month JOURNAL REFERENCE Published FY09 AFTER Science and Technology Review

PHYSICS PUBLICATIONS JLAB NUMBER TITLE OF PAPER AUTHOR(S) Published? Year month JOURNAL REFERENCE Published FY09 AFTER Science and Technology Review JLAB-PHY-08-872 Measurement of unpolarized semi-inclusive pi+ M. Osipenko, M. Ripani, G. Ricco, H. Avakian, R. De Vita, G. Yes 2009 August Phys.Rev.D80:032004,2009 electroproduction off the proton Adams, M.J. Amaryan, P. Ambrozewicz, M. Anghinolfi, G. Asryan, G. Audit, H. Bagdasaryan, N. Baillie, J.P. Ball, N.A. Baltzell, S. Barrow, M. Battaglieri, I. Bedlinskiy, M. Bektasoglu, M. Bellis, N. Benmouna, B.L. Berman, A.S. Biselli, L. Blaszczyk, B.E. Bonner, S. Bouchigny, S. Boiarinov, R. Bradford, D. Branford, W.J. Briscoe, W.K. Brooks, S. Bueltmann, V.D. Burkert, C. Butuceanu, J.R. Calarco, S.L. Careccia, D.S. Carman, A. Cazes, F. Ceccopieri, S. Chen, P.L. Cole, P. Collins, P. Coltharp, P. Corvisiero, D. Crabb, V. Crede, J.P. Cummings, N. Dashyan, R. De Masi, E. De Sanctis, P.V. Degtyarenko, H. Denizli, L. Dennis, A. Deur, K.V. Dharmawardane, K.S. Dhuga, R. Dickson, C. Djalali, G.E. Dodge, J. Donnelly, D. Doughty V. Drozdov, M. Dugger, S. Dytman, O.P. Dzyubak, H. Egiyan, K.S. Egiyan, L. El Fassi, L. Elouadrhiri, P. Eugenio, R. Fatemi, G. Fedotov, G. Feldman, R.J. Feuerbach, H. Funsten, M. Gar¸con, G. Gavalian G.P. Gilfoyle, K.L. Giovanetti, F.X. Girod, J.T. Goetz, E. Golovach, A. Gonenc, C.I.O. Gordon, R.W. Gothe, K.A. Griffioen, M. Guidal, M. Guillo, N. Guler, L. Guo, V. Gyurjyan, C. -

Personalized Immunotherapy Against Several Neuronal and Brain Tumors

(19) TZZ¥¥ T (11) EP 3 539 979 A2 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 18.09.2019 Bulletin 2019/38 C07K 14/47 (2006.01) A61K 38/17 (2006.01) A61K 39/00 (2006.01) C07K 7/06 (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 19166517.3 C07K 7/08 (22) Date of filing: 03.11.2014 (84) Designated Contracting States: • Walter, Steffen AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB Houston, TX 77005 (US) GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO • Hilf, Norbert PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR 72138 Kirchentellinsfurt (DE) Designated Extension States: • Schoor, Oliver BA ME 72074 Tübingen (DE) • Singh, Harpreet (30) Priority: 04.11.2013 GB 201319446 80804 München (DE) 04.11.2013 US 201361899680 P • Kuttruff-Coqui, Sabrina 70794 Filderstadt-Sielmingen (DE) (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in • Song, Colette accordance with Art. 76 EPC: 73760 Ostfildern (DE) 14792834.5 / 3 066 115 (74) Representative: Krauss, Jan (27) Previously filed application: Boehmert & Boehmert 03.11.2014 PCT/EP2014/073588 Anwaltspartnerschaft mbB Pettenkoferstrasse 22 (71) Applicant: Immatics Biotechnologies GmbH 80336 München (DE) 72076 Tübingen (DE) Remarks: (72) Inventors: This application was filed on 01.04.2019 as a • Weinschenk, Toni divisional application to the application mentioned 73773 Aichwald (DE) under INID code 62. • Fritsche, Jens 72144 Dusslingen (DE) (54) PERSONALIZED IMMUNOTHERAPY AGAINST SEVERAL NEURONAL AND BRAIN TUMORS (57) The present invention relates to peptides, nu- ceutical ingredients of vaccine compositions that stimu- cleic acids and cells for use in immunotherapeutic meth- late anti-tumor immune responses. -

Curitiba, 8 De Outubro De 2018 - Edição Nº 2361 - 273 Páginas

Curitiba, 8 de Outubro de 2018 - Edição nº 2361 - 273 páginas Sumário Tribunal de Justiça .......................................................................... 2 Sistemas de Juizados Especiais Cíveis e Criminais .................... 134 Atos da Presidência ..................................................................... 2 Comarca da Capital ......................................................................... 134 Concursos ................................................................................ 2 Direção do Fórum ....................................................................... 134 Supervisão do Sistema da Infância e Juventude ..................... 2 Cível ............................................................................................ 134 Atos da 1ª Vice-Presidência ........................................................ 2 Crime .......................................................................................... 162 Atos da 2ª Vice-Presidência ........................................................ 2 Fazenda Pública .......................................................................... 162 Supervisão do Sistema de Juizados Especiais ........................ 4 Família ........................................................................................ 166 NUPEMEC ............................................................................. 4 Delitos de Trânsito ...................................................................... 166 Secretaria .................................................................................... -

San Mateo County Naturalization Index 1907-1925 San Mateo County Late 1906 Through 1925

San Mateo County Naturalization Index 1907-1925 San Mateo County Genealogical Society 1999 San Mateo County Naturalization Index Volume 2 1907-1925 Project Co-ordinator/ Editor Cath Trindle San Mateo County Genealogical Society © 1999 Record Entry Cath Trindle, Ken & Pam Davis, Mary Lou Grunigen, Margaret Deal, Janice Marshall Proof-reading and Corrections Cath Trindle, Jack Goodwin, Ann Smith, Florence Christensen, Shirley Bittancourt, Vivian Goodwin, Millie Clough © July 1999 San Mateo County Genealogical Society Library of Congress Catalog Car Number 99-071151 Order Copies from the Publisher: San Mateo County Genealogical Society PO Box 5083 San Mateo CA 94402 Table of Contents San Mateo County Oct 1906-1925 ..................................... ii Overview of the Naturalization Records ...................................iv Naturalization Index .................................................. 1 Bibliography ....................................................... 152 SMCGS Archives Project i San Mateo County Naturalization Index 1907-1925 San Mateo County Late 1906 through 1925 When the naturalization process was first slated to change in September of 1906 no one was anticipating the earth shattering moments That were to devastate the San Francisco bay area on April 18. Destruction dotted the peninsula including new court house. But an even greater impact was felt within San Mateo County as this home to only 12000 people in 1900 was flooded with refugees from the completely devastated San Francisco. Development within the county during the ensuing years was strongly influenced by geography. The bay side was served by the San Francisco Railroad which facilitated movement and inspired urban development. Businesses tended to set up on water level sites while residential areas gravitated towards the gently sloping hills. By 1910 the population had nearly doubled to 20,600.