Disarticulating the Artificial Female*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

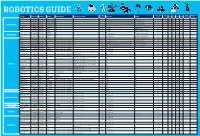

Robotics Section Guide for Web.Indd

ROBOTICS GUIDE Soldering Teachers Notes Early Higher Hobby/Home The Robot Product Code Description The Brand Assembly Required Tools That May Be Helpful Devices Req Software KS1 KS2 KS3 KS4 Required Available Years Education School VEX 123! 70-6250 CLICK HERE VEX No ✘ None No ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Dot 70-1101 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Dash 70-1100 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ready to Go Robot Cue 70-1108 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Codey Rocky 75-0516 CLICK HERE Makeblock No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloadb ale Mblock Software ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ozobot 70-8200 CLICK HERE Ozobot No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ohbot 76-0000 CLICK HERE Ohbot No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads for Windows or Pi ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ SoftBank NAO 70-8893 CLICK HERE No ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Choregraph - free to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Robotics Humanoid Robots SoftBank Pepper 70-8870 CLICK HERE No ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Choregraph - free to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Robotics Ohbot 76-0001 CLICK HERE Ohbot Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads for Windows or Pi ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ FABLE 00-0408 CLICK HERE Shape Robotics Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Free Downloadable ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ VEX GO! 70-6311 CLICK HERE VEX Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ Windows, Mac, -

Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile

FETISHISM AND THE CULTURE OF THE AUTOMOBILE James Duncan Mackintosh B.A.(hons.), Simon Fraser University, 1985 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Communication Q~amesMackintosh 1990 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1990 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : James Duncan Mackintosh DEGREE : Master of Arts (Communication) TITLE OF THESIS: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chairman : Dr. William D. Richards, Jr. \ -1 Dr. Martih Labbu Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Dr. Alison C.M. Beale Assistant Professor \I I Dr. - Jerry Zqlove, Associate Professor, Department of ~n~lish, External Examiner DATE APPROVED : 20 August 1990 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Dissertation: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile. Author : -re James Duncan Mackintosh name 20 August 1990 date ABSTRACT This thesis explores the notion of fetishism as an appropriate instrument of cultural criticism to investigate the rites and rituals surrounding the automobile. -

PROTOTYPE for QUADRUPED ROBOT USING Iot to DELIVER MEDICINES and ESSENTIALS to COVID-19 PATIENT

International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology (IJARET) 4Volume 12, Issue 5, May 2021, pp. 147-155, Article ID: IJARET_12_05_014 Available online at https://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJARET?Volume=12&Issue=5 ISSN Print: 0976-6480 and ISSN Online: 0976-6499 DOI: 10.34218/IJARET.12.5.2021.014 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed PROTOTYPE FOR QUADRUPED ROBOT USING IoT TO DELIVER MEDICINES AND ESSENTIALS TO COVID-19 PATIENT Anita Chaudhari, Jeet Thakur and Pratiksha Mhatre Department of Information Technology, St. John College of Engineering and Management, Palghar, Maharashtra, India ABSTRACT The Wheeled robots cannot work properly on the rocky surface or uneven surface. They consume a lot of power and struggle when they go on rocky surface. To tackle the disadvantages of wheeled robot we replaced the wheels like shaped legs with the spider legs or spider arms. Quadruped robot has complicated moving patterns and it can also move on surfaces where wheeled shaped robots would fail. They can easily walk on rocky or uneven surface. The main purpose of the project is to develop a consistent platform that enables the implementation of steady and fast static/dynamic walking on ground/Platform to deliver medicines to covid-19 patients. The main advantage of spider robot also called as quadruped robot is that it is Bluetooth controlled robot, through the android application, we can control robot from anywhere; it avoids the obstacle using ultrasonic sensor. Key words: Bluetooth module, Quadruped, Rough-terrain robots. Cite this Article: Anita Chaudhari, Jeet Thakur and Pratiksha Mhatre, Prototype for Quadruped Robot using IoT to Deliver Medicines and Essentials to Covid-19 Patient, International Journal of Advanced Research in Engineering and Technology, 12(5), 2021, pp. -

Service Robots 7 Mouser Staff

1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome from the Editor 3 Deborah S. Ray Foreword 6 Grant Imahara Introduction to Service Robots 7 Mouser Staff Sanbot Max: Anatomy of a Service Robot 11 Steven Keeping CIMON Says: Design Lessons from a Robot Assistant in Space 17 Traci Browne 21 Revisiting the Uncanny Valley Jon Gabay Robotic Hands Strive for Human Capabilities 25 Bill Schweber Robotic Gesturing Meets Sign Language 30 Bill Schweber Mouser and Mouser Electronics are registered trademarks of Mouser Electronics, Inc. Other products, logos, and company names mentioned herein may be trademarks of their respective owners. Reference designs, conceptual illustrations, and other graphics included herein are for informational purposes only. Copyright © 2018 Mouser Electronics, Inc. – A TTI and Berkshire Hathaway company. 2 WELCOME FROM THE EDITOR If you’re just now joining us for favorite robots from our favorite This eBook accompanies EIT Video Mouser’s 2018 Empowering shows and movies: Star Wars, Star #3, which features the Henn na Innovation Together™ (EIT) program, Trek, Lost in Space, and Dr. Who. Hotel, the world’s first hotel staffed welcome! This year’s EIT program— by robots. Geared toward efficiency Generation Robot—explores robotics In this EIT segment, we explore and customer comfort, these robots as a technology capable of impacting service robots, which combine not only provide an extraordinary and changing our lives in the 21st principles of automation with that experience of efficiency and comfort, century much like the automobile of robotics to assist humans with but also a fascinating and heart- impacted the 20th century and tasks that are dirty, dangerous, heavy, warming experience for guests. -

Sviluppo Di Un'app Android Per Il Robot Sanbot

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Matematica "Tullio Levi-Civita" Corso di Laurea in Informatica Sviluppo di un’app Android per il robot Sanbot Tesi di laurea triennale Relatore Prof. Mauro Conti Laureando Nicolae Andrei Tabacariu Anno Accademico 2017-2018 Nicolae Andrei Tabacariu: Sviluppo di un’app Android per il robot Sanbot, Tesi di laurea triennale, c Settembre 2018. “Life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated” — Confucius Ringraziamenti Innanzitutto, vorrei esprimere la mia gratitudine al Prof. Mauro Conti, relatore della mia tesi, per l’aiuto e il sostegno fornitomi durante l’attività di stage e la stesura del presente documento. Desidero ringraziare con affetto la mia famiglia e la mia ragazza Erica, che mi hanno sostenuto economicamente ed emotivamente in questi anni di studio, senza i quali probabilmente non sarei mai arrivato alla fine di questo percorso. Desidero poi ringraziare gli amici e i compagni che mi hanno accompagnato in questi anni e che mi hanno dato sostegno ed affetto. Infine porgo i miei ringraziamenti a tutti i componenti di Omitech S.r.l. per l’opportunità di lavorare con loro, per il rispetto e la cordialità con cui mi hanno trattato. Padova, Settembre 2018 Nicolae Andrei Tabacariu iii Indice 1 Introduzione1 1.1 L’azienda . .1 1.2 Il progetto di stage . .2 1.3 Organizzazione dei contenuti . .2 2 Descrizione dello stage3 2.1 Il progetto di stage . .3 2.1.1 Analisi dei rischi . .4 2.1.2 Obiettivi fissati . .4 2.1.3 Pianificazione del lavoro . .5 2.1.4 Interazione con i tutor . -

Android Science - Toward a New Cross-Interdisciplinary Framework

Android Science - Toward a new cross-interdisciplinary framework - Hiroshi ISHIGURO Department of Adaptive Machine Systems, Osaka University [email protected] 1 Android science Appearance and behavior In the evaluation of interactive robots, the performance measures are sub- jective impression of human subjects who interact with the robot and their unconscious reactions, such as synchronized human behaviors in the interac- tions and eye movements. Obviously, both the appearance and behavior of the robots are important factors in this evaluation. There are many technical reports that compare robots with di®erent behaviors. However nobody has focused on appearance in the previous robotics. There many empirical discussions on very simpli¯ed static robots, say dolls. Designing the robot's appearance, especially to give it a humanoid one, was always a role of the industrial designer. However we con- sider this to be a serious problem for developing and evaluating interactive robots. Appearance and behavior are tightly coupled with both each other and these problems, as the results of evaluation change with appearance. In our previous work, we developed several humanoids for communicating with people [3][4][5], as shown in Figure 1. We empirically know the e®ect of appear- ance is as signi¯cant as behaviors in communication. Human brain functions that recognize people support our empirical knowledge. Android Science To tackle the problem of appearance and behavior, two approaches are nec- essary: one from robotics and the other from cognitive science. The ap- proach from robotics tries to build very humanlike robots based on knowl- edge from cognitive science. -

A Low Cost Prototypal Robotic Platform for Underwater Survey in Shallow Water

Advances in Robotics & Mechanical Engineering DOI: 10.32474/ARME.2020.02.000150 ISSN: 2643-6736 Research Article A Low Cost Prototypal Robotic Platform for Underwater Survey in Shallow Water Conte G*, Scaradozzi D and Ciuccoli N Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Informazione, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Italy *Corresponding author: G Conte, Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Informazione, Università Politecnica delle Marche, 60131 Ancona, Received: November 12, 2020 Published: November 30, 2020 Abstract A small, innovative robotic platform for underwater surveys in shallow water is proposed. The platform integrates a The mechatronic structure and the control architecture of the platform are described together with its functional features. Tests commercially available, remotely operated, underwater micro vehicle and a specifically designed and constructed actuated buoy. geolocalizing underwater targets. to validate the implemented constructive solutions are briefly reported, together with functional tests to assess usability in Keywords: Marine robotics; Remotely operated vehicles; Autonomous surface vehicles Introduction functional structure surface and underwater vehicles may be Remotely operated underwater vehicles or ROV are a fundamental tool for inspecting underwater structures in e.g. paper, we describe the development of a small prototypal hybrid costly, complex to operate and logistically demanding. In this robotic platform that overcomes these limiting characteristics. The of an ROV with a surface autonomous vehicle or ASV, which harbour areas, rivers, natural and artificial lakes. Integration platform integrates an actuated buoy, as surface component, and acts as a bridge for communication with a remote station, can The idea of coupling cooperating autonomous surface vehicles and a micro-ROV, as underwater component. The bouy and the micro- significantly increase autonomy, versatility and efficiency [1,2]. -

Poppy: Open-Source, 3D Printed and Fully-Modular Robotic Platform for Science, Art and Education Matthieu Lapeyre

Poppy: open-source, 3D printed and fully-modular robotic platform for science, art and education Matthieu Lapeyre To cite this version: Matthieu Lapeyre. Poppy: open-source, 3D printed and fully-modular robotic platform for science, art and education. Robotics [cs.RO]. Université de Bordeaux, 2014. English. tel-01104641v1 HAL Id: tel-01104641 https://hal.inria.fr/tel-01104641v1 Submitted on 18 Jan 2015 (v1), last revised 13 Jul 2015 (v3) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Poppy: open-source, 3D printed and fully-modular robotic platform for science, art and education. Matthieu Lapeyre September 26, 2014 Version: 0.13 Inria Bordeaux Sud-Ouest Flower team Submitted in fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Specialized in Computer Science Poppy: open-source, 3D printed and fully-modular robotic platform for science, art and education. Matthieu Lapeyre 1. Reviewer Fethi Ben Ouezdou Vice-président à la Valorisation de la Recherche et de l’Innovation Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines 2. Reviewer Jacques Droulez Institut des Systèmes Intelligents et de Robotique UPMC CNRS Supervisors Pierre Yves Oudeyer September 26, 2014 Matthieu Lapeyre Poppy: open-source, 3D printed and fully-modular robotic platform for science, art and educa- tion. -

Creation and Staging of Android Theatre ``Sayonara'' Towards Developing Highly Human-Like Robots

Article Creation and Staging of Android Theatre “Sayonara” towards Developing Highly Human-Like Robots Takenobu Chikaraishi 1,2,* ID , Yuichiro Yoshikawa 2, Kohei Ogawa 2, Oriza Hirata 1,2 and Hiroshi Ishiguro 2 1 COI Site, Tokyo University of the Arts, Tokyo 110-8714, Japan; [email protected] 2 Graduate School of Engineering Science, Osaka University, Suita 565-0871, Japan; [email protected] (Y.Y.); [email protected] (K.O.); [email protected] (H.I.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 4 September 2017; Accepted: 18 October 2017; Published: 2 November 2017 Abstract: Even after long-term exposures, androids with a strikingly human-like appearance evoke unnatural feelings. The behavior that would induce human-like feelings after long exposures is difficult to determine, and it often depends on the cultural background of the observers. Therefore, in this study, we generate an acting performance system for the android, in which an android and a human interact in a stage play in the real world. We adopt the theatrical theory called Contemporary Colloquial Theatre Theory to give the android natural behaviors so that audiences can comfortably observe it even after long-minute exposure. A stage play is created and shown in various locations, and the audiences are requested to report their impressions of the stage and their cultural and psychological backgrounds in a self-evaluating questionnaire. Overall analysis indicates that the audience had positive feelings, in terms of attractiveness, towards the android on the stage even after 20 min of exposure. -

Trudy Barber for the Love of Artifice 3-4-2014

Paper presented at the AISB 50th Symposium ‘Love and Sex with Robots’. Goldsmiths University. 3/4/2014. For the Love of Artifice. Dr. Trudy Barber1. Abstract. Why we need robot sex dolls and in our appreciation of and identification with why there is a growing sub culture of real people arousal inspired by the artificial human. The trying to become them. question of realism and aesthetics has been put 1 forward as a path of engagement in the pursuit of a new theory for robot design as a INTRODUCTION replacement paradigm for notions of the The According to Ferguson, the contemporary uncanny [7], which in turn may alter our sex doll or “fully functioning feminized android reactions of revulsion or excitement when [ … ] appears to have arrived at the threshold of confronted by notions and visions of sex with the boundary between pleasure and science.’2 As robots. Gates in her exploration of deviance has a consequence then, this paper will not re-visit suggested that mechanical dolls and robots popular associated discussions of misogyny, “represent some of our ambivalence about surrealist representations of the female form3, sexuality itself; in a sense we have no control and various interpretations of fetishism [1] [2], over it; that we respond mechanically to stimuli; nor the female robot through science fiction and and that our sexual programming makes us fantasy narrative [3] – but will explore in a helpless.”4 similar fashion as to what has been argued as the “spectre of necrophilia,[a] lens through which In the time of so much mediated ‘upgrade the sexualisation of artificial humans has been culture’[8] at the time of writing, it is argued viewed”[4] In this light, this paper wishes to that part of our evolutionary sexual strategy contrast the notion of making the perfect demonstrates that not only will we wish to fall artificial human as a sex toy - and it’s helplessly in love with our current technologies associations with a deconstruction of what this [9] but we will also wish to become them. -

Design of an Open Source-Based Control Platform for an Underwater Remotely Operated Vehicle Diseño De Una Plataforma De Control

Design of an open source-based control platform for an underwater remotely operated vehicle Luis M. Aristizábal a, Santiago Rúa b, Carlos E. Gaviria c, Sandra P. Osorio d, Carlos A. Zuluaga e, Norha L. Posada f & Rafael E. Vásquez g Escuela de Ingenierías, Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Medellín Colombia. a [email protected], b [email protected], c [email protected], d [email protected], e [email protected], f [email protected], g [email protected] Received: March 25th, de 2015. Received in revised form: August 31th, 2015. Accepted: September 9th, 2015 Abstract This paper reports on the design of an open source-based control platform for the underwater remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Visor3. The vehicle’s original closed source-based control platform is first described. Due to the limitations of the previous infrastructure, modularity and flexibility are identified as the main guidelines for the proposed design. This new design includes hardware, firmware, software, and control architectures. Open-source hardware and software platforms are used for the development of the new system’s architecture, with support from the literature and the extensive experience acquired with the development of robotic exploration systems. This modular approach results in several frameworks that facilitate the functional expansion of the whole solution, the simplification of fault diagnosis and repair processes, and the reduction of development time, to mention a few. Keywords: open-source hardware; ROV control platforms; underwater exploration. Diseño de una plataforma de control basada en fuente abierta para un vehículo subacuático operado remotamente Resumen Este artículo presenta el diseño de una plataforma de control basada en fuente abierta para el vehículo subacuático operado remotamente (ROV) Visor3. -

Design of Android Type Humanoid Robot Albert HUBO€

Design of Android type Humanoid Robot Albert HUBO Jun-Ho Oh David Hanson Won-Sup Kim Il Young Han Jung-Yup Kim Ill-Woo Park Mechanical Division of Mechanical Mechanical Mechanical Engineering Industrial Engineering Engineering Engineering Design Korea Advanced Hanson Robotics Korea Advanced Korea Advanced Korea Advanced Institute of Inc Ewha Womans Institute of Science Institute of Science Institute of Science Science and University and Technology and Technology and Technology Technology Daejeon, Korea Dallas, TX, USA Seoul, Korea Daejeon, Korea Daejeon, Korea Daejeon, Korea [email protected] David@HansonRo kimws@ewha. [email protected]. [email protected]. [email protected] botics.com ac.kr kr ac.kr ist.ac.kr Abstract incompletely. But, the combination of these two factors To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the announcement brought an unexpected result from the mutual effect. of the special relativity theory of Albert Einstein, KAIST The body of Albert HUBO is based on humanoid robot HUBO team and hanson robotics team developed android ‘HUBO’ introduced in 2004[5]. HUBO, the human scale type humanoid robot Albert HUBO which may be the humanoid robot platform with simple structure, can bi-pad world’s first expressive human face on a walking biped walking and independent self stabilize controlling. The head robot. The Albert HUBO adopts the techniques of the of Albert HUBO is made by hanson robotics team and the HUBO design for Albert HUBO body and the techniques techniques of low power consumptions and full facial of hanson robotics for Albert HUBO’s head. Its height and expressions are based on famous, worldwide recognized, weight are 137cm and 57Kg.