Irish Bonds of Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

A Climbers Guide to Gweedore

1 A Climbers Guide to Gweedore By Iain Miller www.uniqueascent.ie 2 Gweedore Gweedore, known locally as Gaoth Dobhair, lives in between Cloughaneely and the Rosses to the south Gweedores coastline stretches for approximately 25km from from Meenaclady in the north to Crolly in the south and it is one of Europe's most densely populated rural areas, it is also the largest Irish speaking parish in Ireland. Gweedore coast along the Wild Atlantic Way can easily be described simply as one enormous Caribbean type sandy beach and as such is an outstanding place to visit in the summer months. Within in the parish of Gweedore there an enormous amount of bouldering and highball rock dotted all over the region, it is simply a case of stopping the car whenever you see rock from the road and going for a look. There are so far two main climbing location both are quite small but will each provide a half day of vertical pleasure. Tor na Dumhcha being the better location and providing immaculate vertical Gola Granite to play on. The Sand Quarry Three short white granite walls are to be found just outside Derrybeg amongst the dunes north east of the pier for Inishmeane. GR8029. Take a left at the first brown beach sign outside of Derrybeg. This laneway L53231 is signposted as Bealach na Gealtachta Slí na Earagail, trá Beach. Park the car above the beach close to the solitary pick-nick table, Walk back across the flat grass to find a secluded granite outcrop located in a bit of a sand pit. -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

The Irish Diaspora in Britain & America

Reflections on 1969 Lived Experiences & Living history (Discussion 6) The Irish Diaspora in Britain & America: Benign or Malign Forces? compiled by Michael Hall ISLAND 123 PAMPHLETS 1 Published January 2020 by Island Publications 132 Serpentine Road, Newtownabbey BT36 7JQ © Michael Hall 2020 [email protected] http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/islandpublications The Fellowship of Messines Association gratefully acknowledge the assistance they have received from their supporting organisations Printed by Regency Press, Belfast 2 Introduction The Fellowship of Messines Association was formed in May 2002 by a diverse group of individuals from Loyalist, Republican and other backgrounds, united in their realisation of the need to confront sectarianism in our society as a necessary means of realistic peace-building. The project also engages young people and new citizens on themes of citizenship and cultural and political identity. Among the different programmes initiated by the Messines Project was a series of discussions entitled Reflections on 1969: Lived Experiences & Living History. These discussions were viewed as an opportunity for people to engage positively and constructively with each other in assisting the long overdue and necessary process of separating actual history from some of the myths that have proliferated in communities over the years. It was felt important that current and future generations should hear, and have access to, the testimonies and the reflections of former protagonists while these opportunities still exist. Access to such evidence would hopefully enable younger generations to evaluate for themselves the factuality of events, as opposed to some of the folklore that passes for history in contemporary society. -

GAH 1XXX/ the Nanticoke & Lenape Indians of NJ Stockton University

GAH 1XXX/ The Nanticoke & Lenape Indians of NJ Stockton University, Spring Semester 2022 Instructor: Jeremy Newman Contact Email: [email protected] Days/Time: TBD Room: TBD Virtual Office Hours: TBD Course Objectives: This course examines the long tribal history and contemporary struggles of the Nanticoke and Lenape Indians of New Jersey. It addresses racial identity, cultural practices, environmentalism and spirituality within the context of tribal sovereignty. Additionally, lectures and course materials counter misinformation and stereotypes. Required Text: Hearth, Amy Hill. “Strong Medicine” Speaks: A Native American Elder Has Her Say. New York: Atria Books, 2014. Course Goals: During the semester students will: - Examine the link between American Indian sovereignty and tribal identity - Develop an appreciation for American Indian culture and traditions - Understand the connection between American Indians and environmentalism Essential Learning Outcomes: For detailed descriptions see: www.stockton.edu/elo - Ethical Reasoning - Creativity & Innovation - Global Awareness Grading: 1) Paper 1 (10%) 2) Paper 2 (10%) 3) Midterm Exam (15%) 4) Final Exam (20%) 5) Paper 3 (35%) 6) Participation (10%) Note: There are no extra credit assignments. Grading Scale: 93-100 (A) 80-82 (B-) 67-69 (D+) 90-92 (A-) 77-79 (C+) 63-66 (D) 87-89 (B+) 73-76 (C) 60-62 (D-) 83-86 (B) 70-72 (C-) 59 and below (F) Withdrawals: September X: Deadline to withdraw with a 100% refund November X: Deadline to withdraw with a W grade Incompletes: The instructor will grant an incomplete only in the rare instance that a student is doing well in class and an illness or emergency makes it impossible to complete the course work before the end of the semester. -

Secret Societies and the Easter Rising

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2016 The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising Sierra M. Harlan Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Harlan, Sierra M., "The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising" (2016). Senior Theses. 49. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF A SECRET: SECRET SOCIETIES AND THE EASTER RISING A senior thesis submitted to the History Faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History by Sierra Harlan San Rafael, California May 2016 Harlan ii © 2016 Sierra Harlan All Rights Reserved. Harlan iii Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the amazing support and at times prodding of my family and friends. I specifically would like to thank my father, without him it would not have been possible for me to attend this school or accomplish this paper. He is an amazing man and an entire page could be written about the ways he has helped me, not only this year but my entire life. As a historian I am indebted to a number of librarians and researchers, first and foremost is Michael Pujals, who helped me expedite many problems and was consistently reachable to answer my questions. -

NMAJH and Partners Internship Program

NMAJH and Partners Internship Program The National Museum of American Jewish History is a leading cultural institution with a vibrant internship program for undergraduate, graduate, and recently graduated students who want to learn about public history, the museum profession, non-profit organizations, and the American Jewish experience. Interns work in specific departments and participate in periodic group experiences, including a two hour weekly Summer Seminar. Interns will be placed according to their interests, experience, and the needs of the Museum. We will also be pleased to discuss a placement to support a specific project of interest to students. Potential placements include: Academic Liaison, CEO / Director’s Office, Curatorial, Development, Education, Facilities Rental & Events Planning, Group Services, Marketing & Communications, Public Programs, and Retail/Operations. For Summer internships, a weekly hourly commitment of 35-40 hours is required. For Fall and Spring internships, a minimum weekly commitment of 8 hours is required. In addition, we collaborate with other Philadelphia cultural institutions for internship opportunities, including the Gershman Y and its Jewish Film Festival, the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies and the Philadelphia History Museum. Interns at these institutions are included in our extended internship community. Requests for internships at these institutions are coordinated through the NMAJH internship program and application process. We offer a limited number of paid internships to students with demonstrated financial need. These opportunities are made possible through a generous challenge grant from an anonymous national foundation, with the support of the Connelly Foundation, the Hassel Foundation and a local anonymous donor helping the Museum to meet that challenge. -

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

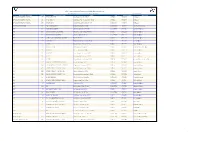

This Includes Donegal, Sligo, Leitrim

CHO 1 - Service Provider Resumption of Adult Day Services Portal For further information please contact your service provider directly. Last updated 2/03/21 Service Provider Organisation Location Id Day Service Location Name Address Area Telephone Number Email Address ADVOCATES FOR PERSONAL POTENTIAL 3464 APP DONEGAL TOWN Quay Street, Donegal Town, F94 Dr70 DONEGAL 087 1235873 [email protected] ADVOCATES FOR PERSONAL POTENTIAL 521 APP LETTERKENNY Unit Bg9, Justice Walsh Road, Letterkenny, F92 Ye2f DONEGAL 087 1235873 [email protected] ADVOCATES FOR PERSONAL POTENTIAL 2436 APP SLIGO LEITRIM Old Dublin Road, Carrickonshannon, N41 Yy68 SLIGO/LEITRIM 087 1235873 [email protected] GATEWAY COMMUNITY CARE 3610 GCC ACTIVE INCLUSION Ballybeg, Knocknahur, Sligo F91 Dy72 SLIGO/LEITRIM 087 1099406 [email protected] HSE 2440 ACORN RESOURCE CENTRE Clarion Road, Ballytivnan, Sligo F91 Nh51 SLIGO/LEITRIM 071 9148230 [email protected] HSE 2426 AURORA COMMUNITY INCLUSION HUB Milltown House, Tulari, Carndonagh F93 Hw24 DONEGAL 074 9322503 [email protected] HSE 163 BALLYTIVNAN TRAINING CENTRE Clarion Road, Ballytivnan, F91 Nd2n SLIGO/LEITRIM 071 9143214 [email protected] HSE 415 CASHEL NA COR COMMUNITY INCLUSION HUB Buncrana, F93 P527 DONEGAL 074 9321057 [email protected] HSE 3247 CI BALLYRAINE Ballyraine Industrial Estate, Letterkenny, F92 Dy24 DONEGAL 074 9121545 [email protected] HSE 3626 CI DAWN Justice Walsh Road, Letterkenny, F92 Ea2w DONEGAL 074 9200276 [email protected] HSE 3627 CI DONEGAL TOWN Unit B, Quay Street, Donegal -

Roinn Cosanta

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU. OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 766 Witness Dr. Patrick McCartan, Karnak, The Burnaby, Greystones, Co. Wicklow. Identity. Member of Supreme Council of I.R.B.; O/C. Tyrone Volunteers, 1916; Envoy of Dail Eireann to U.S.A. and Rudsia. Subject. (a) National events, 1900-1917; - (b) Clan na Gael, U.S.A. 1901 ; (C) I.R.B. Dublin, pre-1916. Conditions, it any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.63 Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENT OF DR. PATRICK McCARTAN, KARNAK. GREYSTONES, CO. WICKLOW. CONTENTS. Pages details and schooldays 1 - 5 Personal Departure for U.S.A. 5 Working for my living and sontinuing studies U.S.A. 5 - 7 in Return to Ireland in 1905 8 My initiation into the Hibernians and, later, the Clan-na-Gael in the U.S.A 8 Clan-na-Gael meeting addressed by Major McBride and Maud Gonne and other Clan-na-Gael activities 9 - 11 of the "Gaelic American". 12 Launching My transfer from the Clan-na-Gael to the I.R.E. in Dublin. Introduced to P.T. Daly by letter from John Devoy. 12 - 13 Some recollections of the Dublin I.R.B. and its members 13 - 15 Circle Fist Convention of Sinn Fein, 1905. 15 - 16 Incident concerning U.I.L. Convention 1905. 17 First steps towards founding of the Fianna by Countess Markievicz 1908. 18 My election to the Dublin Corporation. First publication of "Irish Freedom". 19 Commemoration Concert - Emmet 20 21. action by I.R.B. -

Book Auction Catalogue

1. 4 Postal Guide Books Incl. Ainmneacha Gaeilge Na Mbail Le Poist 2. The Scallop (Studies Of A Shell And Its Influence On Humankind) + A Shell Book 3. 2 Irish Lace Journals, Embroidery Design Book + A Lace Sampler 4. Box Of Pamphlets + Brochures 5. Lot Travel + Other Interest 6. 4 Old Photograph Albums 7. Taylor: The Origin Of The Aryans + Wilson: English Apprenticeship 1603-1763 8. 2 Scrap Albums 1912 And Recipies 9. Victorian Wildflowers Photograph Album + Another 10. 2 Photography Books 1902 + 1903 11. Wild Wealth – Sears, Becker, Poetker + Forbeg 12. 3 Illustrated London News – Cornation 1937, Silver Jubilee 1910-1935, Her Magesty’s Glorious Jubilee 1897 13. 3 Meath Football Champions Posters 14. Box Of Books – History Of The Times etc 15. Box Of Books Incl. 3 Vols Wycliff’s Opinion By Vaughan 16. Box Books Incl. 2 Vols Augustus John Michael Holroyd 17. Works Of Canon Sheehan In Uniform Binding – 9 Vols 18. Brendan Behan – Moving Out 1967 1st Ed. + 3 Other Behan Items 19. Thomas Rowlandson – The English Dance Of Death 1903. 2 Vols. Colour Plates 20. W.B. Yeats. Sophocle’s King Oedipis 1925 1st Edition, Yeats – The Celtic Twilight 1912 And Yeats Introduction To Gitanjali 21. Flann O’Brien – The Best Of Myles 1968 1st Ed. The Hard Life 1973 And An Illustrated Biography 1987 (3) 22. Ancient Laws Of Ireland – Senchus Mor. 1865/1879. 4 Vols With Coloured Lithographs 23. Lot Of Books Incl. London Museum Medieval Catalogue 24. Lot Of Irish Literature Incl. Irish Literature And Drama. Stephen Gwynn A Literary History Of Ireland, Douglas Hyde etc 25.