The Irish Diaspora in Britain & America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

1/- D E M O C R

MOVING FOR 1/- A UNITED DEMOCRAT No. 289 SEPTEMBER 1968 IRELAND APPEAL TO MANY ORGANISATIONS LONDON IRISH MARCH People of six counties at end of tether FOR CIVIL RIGHTS ^J NLESS something is done soon to end the injustices Which exist in British occupied Ireland there is going to be an explosion there. Cheers from onlookers The people are getting to the This is the message of the great in Camden have undertaken to end of their tether, with end- meeting and parade from Coal- join with the Association in poster island to Dungannon on Saturday, less unemployment, low wages, parades. They see the struggle for August 24th, 1968, a date to be QNLOOKERS the pavements when members of the shortage of housing, all backed on cheered remembered. Irish independence as on a par ^ Connolly Association, Clann na hEireann and the Republican up by religious discrimination, with the struggle against the dis- Party walked from Manette Street, Charing Cross Road, to Marble gerrymandering and police dic- This is the message that has graceful war in Vietnam. Arch to demand the introduction of normal democracy into the tatorship. come from Ireland to the Connolly six counties of north east Ireland- Association in London, and to which the Association intends to CONFERENCE The parade took place on Sun- react as its duty is. In order to get the new campaign day, July 28th, and was followed under way Central London Con- by a meeting in Hyde Park, at which the speakers were Sean Red- INITIATIVE nolly Association is calling a con- ference on September 11th of mond, General Secretary of the Central London Branch of the Connolly Association; Desmond interested organisations in the two Association is to take the initia- Greaves; Robert Heatley and Jack central boroughs of Camden and tive in a new campaign which it Henry, the building workers' ste- Islington. -

Accounting and Discounting for the International Contacts of the Provisional Irish Republican Army by Michael Mckinley

Conflict Quarterly Of "Alien Influences": Accounting and Discounting for the International Contacts of the Provisional Irish Republican Army by Michael McKinley NATURE OF INTERNATIONAL CONTACTS In a world where nation states are unanimous in their disavowal of terrorism — even if they are incapable of unanimously agreeing on a defini tion of what it is they are disavowing — and in a Western Europe which regards separatist and irredentist claims as anathema, mere is a natural ten dency for those who are so excluded to make common cause where they might Disparate as these groups are, they really have only themselves to meet as equals; though they might wish to be nation states or represent nation states in the fullness of time, they exist until then as interlopers in the relations between states: seldom invited and then almost always disappointed by their reception. It is a world with which the Provisional Irish Republican Army and its more political expression, Sinn Fein, are entirely familiar and also one in which, given their history, political complexion, strategy and objectives, it would be extraordinarily strange for them not to have a wide range of inter national contacts. But potent as the reflex of commonality by exclusion is, it does not completely determine these linkages because to argue this is to argue on the basis of default rather than purpose. For the Provisionals there is a utility not only of making such contacts but also in formalizing them where possible within the movements' organizational structure. Thus, in 1976 the Sinn Fein Ard Fheis moved to establish, under the directorship of Risteard Behal, a Foreign Affairs Bureau, with Behal as its first "sort of roving Euro pean ambassador . -

Miscellaneous Notes on Republicanism and Socialism in Cork City, 1954–69

MISCELLANEOUS NOTES ON REPUBLICANISM AND SOCIALISM IN CORK CITY, 1954–69 By Jim Lane Note: What follows deals almost entirely with internal divisions within Cork republicanism and is not meant as a comprehensive outline of republican and left-wing activities in the city during the period covered. Moreover, these notes were put together following specific queries from historical researchers and, hence, the focus at times is on matters that they raised. 1954 In 1954, at the age of 16 years, I joined the following branches of the Republican Movement: Sinn Féin, the Irish Republican Army and the Cork Volunteers’Pipe Band. The most immediate influence on my joining was the discovery that fellow Corkmen were being given the opportunity of engag- ing with British Forces in an effort to drive them out of occupied Ireland. This awareness developed when three Cork IRA volunteers were arrested in the North following a failed raid on a British mil- itary barracks; their arrest and imprisonment for 10 years was not a deterrent in any way. My think- ing on armed struggle at that time was informed by much reading on the events of the Tan and Civil Wars. I had been influenced also, a few years earlier, by the campaigning of the Anti-Partition League. Once in the IRA, our initial training was a three-month republican educational course, which was given by Tomas Óg MacCurtain, son of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Tomas MacCurtain, who was murdered by British forces at his home in 1920. This course was followed by arms and explosives training. -

Irish Democrat." He Regards As Tripartite

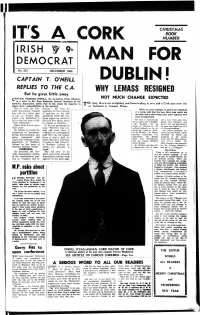

CHRISTMAS BOOK ITS A CORK NUMBER IRISH 9 DEMOCRAT MAN FOR No. 267 DECEMB ER 1966 CAPTAIN T. O'NEILL DUBLIN! REPLIES TO THE C.A. WHY LEMASS RESIGNED But- he gives little away £APTAIN TERENCE O'NEILL, the six-county Prime Minister, NOT MUCH CHANGE EXPECTED in a letter to Mr. Sean Redmond, General Secretary of the Connolly Association, denies that he lias urged the majority to 'HE long drawn-out in-fighting and horse-trading is over and a Cork man now sits ignore their responsibilities to the minority. as Taoiseach in Leinster House. This is what the Con- genious." He rests his While no great changes of policy are expected, nolly Association charged argument for the retention it is being said that the new Cork man could not him with in a letter sent of partition on the 1925 do much worse than those from other counties who to him on October 26th, agreement which Mr. Cos- have preceded him. which was published in grave signed on behalf of full in the last issue of the the Irish Free State, which The team is substantially and a half, "Posts and Tele- Mr. Lemass's, but re-shuffled. "Irish Democrat." he regards as tripartite. graphs and Transport and Mr. Haughey will no Power," but this may shortly Apart from this he gives In his last paragraph he longer be plagued by the be made one under the title little away. says: "Between your out- militant farmers, as he re- of "Communications." He refuses to accept the look and mine there is places Mr. -

Roinn Cosanta

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU. OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 766 Witness Dr. Patrick McCartan, Karnak, The Burnaby, Greystones, Co. Wicklow. Identity. Member of Supreme Council of I.R.B.; O/C. Tyrone Volunteers, 1916; Envoy of Dail Eireann to U.S.A. and Rudsia. Subject. (a) National events, 1900-1917; - (b) Clan na Gael, U.S.A. 1901 ; (C) I.R.B. Dublin, pre-1916. Conditions, it any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.63 Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENT OF DR. PATRICK McCARTAN, KARNAK. GREYSTONES, CO. WICKLOW. CONTENTS. Pages details and schooldays 1 - 5 Personal Departure for U.S.A. 5 Working for my living and sontinuing studies U.S.A. 5 - 7 in Return to Ireland in 1905 8 My initiation into the Hibernians and, later, the Clan-na-Gael in the U.S.A 8 Clan-na-Gael meeting addressed by Major McBride and Maud Gonne and other Clan-na-Gael activities 9 - 11 of the "Gaelic American". 12 Launching My transfer from the Clan-na-Gael to the I.R.E. in Dublin. Introduced to P.T. Daly by letter from John Devoy. 12 - 13 Some recollections of the Dublin I.R.B. and its members 13 - 15 Circle Fist Convention of Sinn Fein, 1905. 15 - 16 Incident concerning U.I.L. Convention 1905. 17 First steps towards founding of the Fianna by Countess Markievicz 1908. 18 My election to the Dublin Corporation. First publication of "Irish Freedom". 19 Commemoration Concert - Emmet 20 21. action by I.R.B. -

Official Irish Republicanism: 1962-1972

Official Irish Republicanism: 1962-1972 By Sean Swan Front cover photo: Detail from the front cover of the United Irishman of September 1971, showing Joe McCann crouching beneath the Starry Plough flag, rifle in hand, with Inglis’ baker in flames in the background. This was part of the violence which followed in reaction to the British government’s introduction of internment without trial on 9 August 1971. Publication date 1 February 2007 Published By Lulu ISBN 978-1-4303-0798-3 © Sean Swan, 2006, 2007 The author can be contacted at [email protected] Contents Acknowledgements 6 Chapter 1. Introduction 7 Chapter 2. Context and Contradiction 31 Chapter 3. After the Harvest 71 Chapter 4. 1964-5 Problems and Solutions 119 Chapter 5. 1966-1967: Control and 159 Reaction Chapter 6: Ireland as it should be versus Ireland as it is, January 1968 to August 203 1969 Chapter 7. Defending Stormont, Defeating the EEC August 1969 to May 283 1972 Chapter 8. Conclusion 361 Appendix 406 Bibliography 413 Acknowledgements What has made this book, and the thesis on which it is based, possible is the access to the minutes and correspondence of Sinn Fein from 1962 to 1972 kindly granted me by the Ard Comhairle of the Workers’ Party. Access to the minutes of the Wolfe Tone Society and the diaries of C. Desmond Greaves granted me by Anthony Coughlan were also of tremendous value and greatly appreciated. Seamus Swan is to be thanked for his help with translation. The staff of the Linen Hall Library in Belfast, especially Kris Brown, were also very helpful. -

2001-; Joshua B

The Irish Labour History Society College, Dublin, 1979- ; Francis Devine, SIPTU College, 1998- ; David Fitzpat- rick, Trinity College, Dublin, 2001-; Joshua B. Freeman, Queen’s College, City Honorary Presidents - Mary Clancy, 2004-; Catriona Crowe, 2013-; Fergus A. University of New York, 2001-; John Horne, Trinity College, Dublin, 1982-; D’Arcy, 1994-; Joseph Deasy, 2001-2012; Barry Desmond, 2013-; Francis Joseph Lee, University College, Cork, 1979-; Dónal Nevin, Dublin, 1979- ; Cor- Devine, 2004-; Ken Hannigan, 1994-; Dónal Nevin, 1989-2012; Theresa Mori- mac Ó Gráda, University College, Dublin, 2001-; Bryan Palmer, Queen’s Uni- arty, 2008 -; Emmet O’Connor, 2005-; Gréagóir Ó Dúill, 2001-; Norah O’Neill, versity, Kingston, Canada, 2000-; Henry Patterson, University Of Ulster, 2001-; 1992-2001 Bryan Palmer, Trent University, Canada, 2007- ; Bob Purdie, Ruskin College, Oxford, 1982- ; Dorothy Thompson, Worcester, 1982-; Marcel van der Linden, Presidents - Francis Devine, 1988-1992, 1999-2000; Jack McGinley, 2001-2004; International Institute For Social History, Amsterdam, 2001-; Margaret Ward, Hugh Geraghty, 2005-2007; Brendan Byrne, 2007-2013; Jack McGinley, 2013- Bath Spa University, 1982-2000. Vice Presidents - Joseph Deasy, 1999-2000; Francis Devine, 2001-2004; Hugh Geraghty, 2004-2005; Niamh Puirséil, 2005-2008; Catriona Crowe, 2009-2013; Fionnuala Richardson, 2013- An Index to Saothar, Secretaries - Charles Callan, 1987-2000; Fionnuala Richardson, 2001-2010; Journal of the Irish Labour History Society Kevin Murphy, 2011- & Assistant Secretaries - Hugh Geraghty, 1998-2004; Séamus Moriarty, 2014-; Theresa Moriarty, 2006-2007; Séan Redmond, 2004-2005; Fionnuala Richardson, Other ILHS Publications, 2001-2016 2011-2012; Denise Rogers, 1995-2007; Eddie Soye, 2008- Treasurers - Jack McGinley, 1996-2001; Charles Callan, 2001-2002; Brendan In September, 2000, with the support of MSF (Manufacturing, Science, Finance – Byrne, 2003-2007; Ed. -

Trotskyists Debate Ireland Workers’ Liberty Volume 3 No 45 October 2014 £1 Reason in Revolt Trotskyists Debate Ireland 1939, Mid-50S, 1969

Trotskyists debate Ireland Workers’ Liberty Volume 3 No 45 October 2014 £1 www.workersliberty.org Reason in revolt Trotskyists debate Ireland 1939, mid-50s, 1969 1 Workers’ Liberty Trotskyists debate Ireland Introduction: freeing Marxism from pseudo-Marxist legacy By Sean Matgamna “Since my early days I have got, through Marx and Engels, Slavic peoples; the annihilation of Jews, gypsies, and god the greatest sympathy and esteem for the heroic struggle of knows who else. the Irish for their independence” — Leon Trotsky, letter to If nonetheless Irish nationalists, Irish “anti-imperialists”, Contents Nora Connolly, 6 June 1936 could ignore the especially depraved and demented charac - ter of England’s imperialist enemy, and wanted it to prevail In 1940, after the American Trotskyists split, the Shachtman on the calculation that Catholic Nationalist Ireland might group issued a ringing declaration in support of the idea of gain, that was nationalism (the nationalism of a very small 2. Introduction: freeing Marxism from a “Third Camp” — the camp of the politically independent part of the people of Europe), erected into absolute chauvin - revolutionary working class and of genuine national liberation ism taken to the level of political dementia. pseudo-Marxist legacy, by Sean Matgamna movements against imperialism. And, of course, the IRA leaders who entered into agree - “What does the Third Camp mean?”, it asked, and it ment with Hitler represented only a very small segment of 5. 1948: Irish Trotskyists call for a united replied: Irish opinion, even of generally anti-British Irish opinion. “It means Czech students fighting the Gestapo in the The presumption of the IRA, which literally saw itself as Ireland with autonomy for the Protestant streets of Prague and dying before Nazi rifles in the class - the legitimate government of Ireland, to pursue its own for - rooms, with revolutionary slogans on their lips. -

Bodenstown: 200Th Anniversary of the Founding of the United Irishmen

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Materials Workers' Party of Ireland 1991-10 Bodenstown: 200th Anniversary of the Founding of the United Irishmen The Workers'Party Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/workerpmat Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation The Workers'Party, "Bodenstown: 200th Anniversary of the Founding of the United Irishmen" (1991). Materials. 122. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/workerpmat/122 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Workers' Party of Ireland at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Materials by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Bodenstown October 1991 200th Anniversary of the Founding of The United Irishmen LESSONS FOR TODAY Cllr.Tomas MacGiolla T.D. Introduction by Cathal Goulding 200th Anniversary of the Founding of The United Irishmen LESSONS FOR TODAY INTRODUCTION When I was asked to write an introduction to Tomas Mac Giolla's October 1991 Bodenstown speech I accepted the task with pleasure. Tomas Mac Giolla has been one of my closest comrades and valued friends for over thirty years of struggle. In considering his Bodenstown speech I began to think about Tomas Mac Giolla's unique and unforgettable contribution to the life of our party and country. Tomas Mac Giolla blazed a lot of trails for socialism and for authentic Republicanism in this country. For Mac Giolla, its been a 40 year job. -

Hibernian Charity Board Reorganized Frontlines of the Pro-Life Fight Are In

DATED MATERIAL DATED ® —HIS EMINENCE, PATRICK CARDINAL O’DONNELL of Ireland Vol. LXXXIII No. 6 USPS 373340 December 2016 - January 2017 1.50 Hibernian Charity Board reorganized Joseph C. Casler Michael P. Joyce II Billy Lawless Joseph J. Norton, Ph.D. Brian O’Dwyer During the 2016 National Convention in Atlantic City, the general assembly authorized the National Board to reconstitute the National Hibernian Charity. The Hibernian Charity was organized years ago to raise money for the many charitable works of our National Order and was long overdue an update. The NHC was designated by the IRS, as a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt non-profit corporation which provides an additional incentive for charitable donations. Donors to NHC may claim a tax deduction for their donations according to the law. As a tax-exempt non-profit corporation, NHC is also poised to compete for grants from the nation’s largest philanthropic foundations that restrict their gifts to only tax-exempt non-profit corporations. Pursuant to the charge of the general assembly, the National Board revised the Bylaws of the NHC Constitution to modern operations, conform to best business practices and permit NHC to effectively compete for grant funding. Patrick Sean Ryan Ted M. Sullivan John Patrick Walsh One of the Bylaws changes was to change the title of the Board of Directors to Board of Trustees. The National Board believes the title “Trustee” better conveys the fiduciary responsibility entrusted to Board members and will aide them in their mission. The Michael P. Joyce II, Austin, Texas. Mike is Vice President of Operations & Research purpose of this Board of Trustees is not only to administer funding to our many charities, for the Texas Business Leadership Council (TBLC) in Austin and has eight years of but to seek funds from the many philanthropic individuals and organizations across the experience in the non-profit sector.