John Backhouse Topham

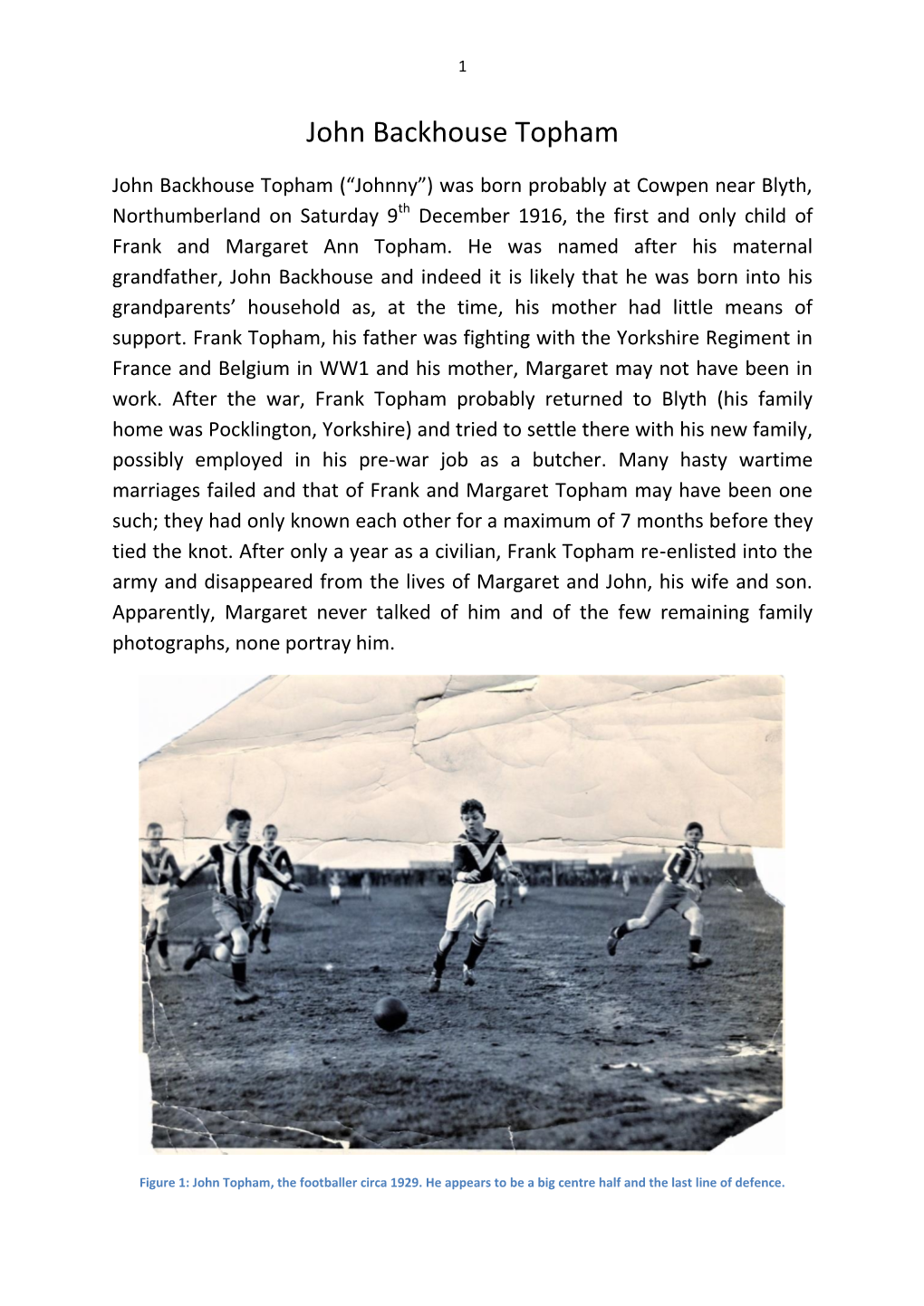

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S D Awn to D U Sk C Ha Lle Nge D a Vid M Onks & R U Sse Ll W Aughman 1 5 Th Ju Ly 2 0

Pooley's Dawn to Dusk Challenge David Monks & Russell Waughman 15th July 2016 A David Monks and Rusty Waughman Production © 2017 Flight Log David Monks and Russell "Rusty" Waughman Flight Date: 15th July 2016 Foreword As a young pilot, the Pooleys Dawn to Dusk Challenge appealed to my sense of adventure, I had wanted to enter since qualifying as a pilot 1995.The hardest part was finding an inspiring theme to make sure your challenge flight stands head and shoulders above the rest. Any pilots ego will tell you that "you are in it to win it"! Some 21 years later, I had the pleasure of meeting a remarkable man, Lancaster pilot Flight Lieutenant Russell "Rusty" Reay Waughman AFC, DFC, Legion D'Honneur RAF (rtd). A sprightly then 93 year old, he gave me the inspiration and the unique story to finally enter the challenge. The theme was very personal to Rusty as it retraced his war-time footsteps round the RAF camps he served at whilst serving with 101 (Special Duties) Squadron, many of them he hadn't seen since the 1940s, he hadn't seen his base, Ludford Magna, from the air since the night before D-Day. After just over eight hours of flying with Rusty, the privilege afforded to me that day outweighed the importance of my pilot ego hoping to win. I couldn't say the same for Rusty. I'm fortunate to count Rusty as a friend. 1 2 Introduction David Monks bought his first helicopter when he was 27 years of age, a Robinson R22 purchased as he completed his PPL(H). -

Compton Chamberlayne Roll of Honour M.T.G. HENRY. DFC

Compton Chamberlayne Roll of Honour Lest we Forget World War II FLIGHT LIEUTENANT M.T.G. HENRY. DFC. PILOT ROYAL AIR FORCE 13TH JANUARY, 1941 AGE 28 IN VERY LOVING MEMORY ©Wiltshire OPC Project/Cathy Sedgwick/2012 Michael Thomas Gibson HENRY Michael Thomas Gibson HENRY was the only son of Thomas Gibson HENRY and Edith Margaret HENRY (nee Castle). Michael’s birth was registered in the September Quarter of 1912 in the district of Birkenhead, Cheshire. (The 1911 Census records Michael’s father – Thomas Gibson Henry as a 40 year old, single, solicitor, visiting Septimus Castle, aged 55, a solicitor, widowed & his 3 adult children – one of whom was Edith Margaret Castle, aged 26, Thomas Henry’s future wife. The address recorded was Park Lodge, Bidstow, Birkenhead & had 6 servants. Thomas Gibson HENRY married Edith M Castle in the June Quarter of 1911 at Birkenhead, Cheshire. 2 years after the birth of their only son, Thomas Gibson & Edith Margaret HENRY had a daughter – Elizabeth G HENRY, whose birth was registered in the September Quarter of 1914.) Michael Thomas Gibson HENRY attended the Sedbergh School in Cumbria, as part of Sedgwick House, from 1926 until 1930. Michael’s younger sister, Elizabeth G Henry married Frederick S Wakeham, in the district of Wirral, in the March quarter of 1937. Michael Thomas Gibson HENRY was granted a short service commission as Acting Pilot Officer with the Royal Air Force, on probation, on 5th July, 1937. (Source: London Gazette 20th July, 1937) M.T.G. HENRY was posted to No. 7 Flying Training School, Peterborough, July 17th, 1937. -

Archie to SAM a Short Operational History of Ground-Based Air Defense

Archie to SAM A Short Operational History of Ground-Based Air Defense Second Edition KENNETH P. WERRELL Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama August 2005 Air University Library Cataloging Data Werrell, Kenneth P. Archie to SAM : a short operational history of ground-based air defense / Kenneth P. Werrell.—2nd ed. —p. ; cm. Rev. ed. of: Archie, flak, AAA, and SAM : a short operational history of ground- based air defense, 1988. With a new preface. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-136-8 1. Air defenses—History. 2. Anti-aircraft guns—History. 3. Anti-aircraft missiles— History. I. Title. 358.4/145—dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public re- lease: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii In memory of Michael Lewis Hyde Born 14 May 1938 Graduated USAF Academy 8 June 1960 Killed in action 8 December 1966 A Patriot, A Classmate, A Friend THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii DEDICATION . iii FOREWORD . xiii ABOUT THE AUTHOR . xv PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION . xvii PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION . xix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . xxi 1 ANTIAIRCRAFT DEFENSE THROUGH WORLD WAR II . 1 British Antiaircraft Artillery . 4 The V-1 Campaign . 13 American Antiaircraft Artillery . 22 German Flak . 24 Allied Countermeasures . 42 Fratricide . 46 The US Navy in the Pacific . -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 28

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 28 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Photographs credited to MAP have been reproduced by kind permission of Military Aircraft Photographs. Copies of these, and of many others, may be obtained via http://www.mar.co.uk Copyright 2003: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2003 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Mothmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS A NEW LOOK AT ‘THE WIZARD WAR’ by Dr Alfred Price 15 100 GROUP - ‘CONFOUND AND…’ by AVM Jack Furner 24 100 GROUP - FIGHTER OPERATIONS by Martin Streetly 33 D-DAY AND AFTER by Dr Alfred Price 43 MORNING DISCUSSION PERIOD 51 EW IN THE EARLY POST-WAR YEARS – LINCOLNS TO 58 VALIANTS by Wg Cdr ‘Jeff’ Jefford EW DURING THE V-FORCE ERA by Wg Cdr Rod Powell 70 RAF EW TRAINING 1945-1966 by Martin Streetly 86 RAF EW TRAINING 1966-94 by Wg Cdr Dick Turpin 88 SOME THOUGHTS ON PLATFORM PROTECTION SINCE 92 THE GULF WAR by Flt Lt Larry Williams AFTERNOON DISCUSSION PERIOD 104 SERGEANTS THREE – RECOLLECTIONS OF No -

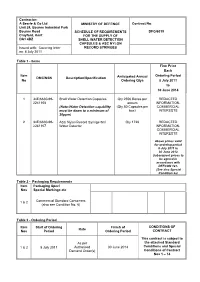

Name & Address Of

Contractor: A Searle & Co Ltd MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Contract No: Unit 24, Bourne Industrial Park Bourne Road SCHEDULE OF REQUIREMENTS DFG/6019 Crayford, Kent FOR THE SUPPLY OF DA1 4BZ SHELL WATER DETECTION CAPSULES & ASC NYLON Issued with: Covering letter RECORD SYRINGES on: 8 July 2011 Table 1 - Items Firm Price Each Item Ordering Period DMC/NSN Description/Specification Anticipated Annual No Ordering Qtys 8 July 2011 to 30 June 2014 1 34E/6630-99- Shell Water Detection Capsules Qty 2556 Boxes per REDACTED 2241108 annum INFORMATION- (Note-Water Detection capability (Qty 80 Capsules per COMMERCIAL must be down to a minimum of box) INTERESTS 30ppm) 2 34E/6630-99- ASC Nylon Record Syringe 5ml Qty 1728 REDACTED 2241107 Water Detector INFORMATION- COMMERCIAL INTERESTS Above prices valid for ordering period 8 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. Subsequent prices to be agreed in accordance with DEFCON 127. (See also Special Condition 2a) Table 2 - Packaging Requirements Item Packaging Spec/ Nos Special Markings etc Commercial Standard Containers 1 & 2 (also see Condition No. 6) Table 3 - Ordering Period Item Start of Ordering Finish of CONDITIONS OF Rate Nos Period Ordering Period CONTRACT This contract is subject to As per the attached Standard 1 & 2 8 July 2011 Authorised 30 June 2014 Conditions and Special Demand Order(s) Conditions of Contract Nos 1 – 14 DFG/6019 STANDARD CONDITIONS OF CONTRACT The following Defence Conditions (DEFCONs) shall apply: DEFCON 5 (Edn 07/99) - MOD Forms 640 – Advice and Inspection Note DEFCON 5J (Edn 07/08) - Unique Identifiers DEFCON 68 (Edn 05/10) - Supply of Hazardous Articles and Substances DEFCON 76 (Edn 12/06) - Contractor’s Personnel at Government Establishments DEFCON 127 (Edn 10/04) - Price Fixing Condition for Contracts of Lesser Value DEFCON 129 (Edn 07/08) - Packaging (For Articles other than Ammunition and Explosives) – see also Condition No 6 Note: For the purposes of this Contract Clause 12 - Spares Price Labelling is not applicable. -

Dropzone Issue 2

HARRINGTON AVIATION MUSEUMS HARRINGTON AVIATION MUSEUMS V OLUME 6 I SSUE 2 THE DROPZONE J ULY 2008 Editor: John Harding Publisher: Fred West MOSQUITO BITES INSIDE THIS ISSUE: By former Carpetbagger Navigator, Marvin Edwards Flying the ‘Mossie’ 1 A wooden plane, a top-secret mission and my part in the fall of Nazi Germany I Know You 3 Firstly (from John Harding) a few de- compared to the B-24. While the B- tails about "The Wooden Wonder" - the 24’s engines emitted a deafening roar, De Havilland D.H.98 Mosquito. the Mossie’s two Rolls Royce engines Obituary 4 seemed to purr by comparison. Al- It flew for the first time on November though we had to wear oxygen masks Editorial 5 25th,1940, less than 11 months after due to the altitude of the Mossie’s the start of design work. It was the flight, we didn’t have to don the world's fastest operational aircraft, a heated suits and gloves that were Valencay 6 distinction it held for the next two and a standard for the B-24 flights. Despite half years. The prototype was built se- the deadly cold outside, heat piped in Blue on Blue 8 cretly in a small hangar at Salisbury from the engines kept the Mossie’s Hall near St.Albans in Hertfordshire cockpit at a comfortable temperature. Berlin Airlift where it is still in existence. 12 Only a handful of American pilots With its two Rolls Royce Merlin en- flew in the Mossie. Those who did had gines it was developed into a fighter some initial problems that required and fighter-bomber, a night fighter, a practice to correct. -

20 on to Berlin, November-December 1943

20 On to Berlin, November-December 1943 In the four weeks following the 22/23 October raid on Kassel, Bomber Com mand attempted only one large operation, when 577 Lancasters and Halifaxes were sent to Dtisseldorf on 3/4 November 1943. Although not included in the Casablanca or Pointblank lists ,* Dtisseldorf was home to several aircraft com ponents plants and, in the view of MEW, was 'as important as Essen and Duisburg .. so far as the production of armaments and general engineering is concerned.' A raid on the city could, therefore, be justified and defended as meeting the spirit, if not the letter, of the two most recent Allied bombing directives.' Target indicators were easily seen through the ground haze, and No 6 Group crews left the target area convinced that the raid had been a success. 'During the early stages ... fires appear to have been somewhat scattered but as the attack progressed a large concentration was observed around the markers and smoke could be seen rising up to 8/rn,ooo ft. Several large explosions are reported notably at 1947 hrs, 1950 hrs, 1955 hrs, 2003 hrs. Flames were observed rising to 8/900 ft from this last explosion and the glow of fires could be seen for a considerable distance on the return journey. ' 2 Photographic reconnaissance missions mounted after the operation confirmed their opinion, as considerable damage was caused to both industrial and residential areas. Equally encouraging, while some German fighters intervened energetically, the overall 3.1 per cent and No 6 Group's 3-47 per cent loss rates were low for operations over this part of Germany, and were attributed to the successful feint attack mounted over Cologne. -

Natten Mellem Den 5. Og 6. Marts Først På Aftenen Den 5

I begyndelsen af marts 1945 var der store ødelæggelser i Stettin efter amerikanske og især britiske angreb. Især Bomber Commands angreb i august 1944 forårsagede store ødelæggelser i byen, der var en vigtig havneby. De vestallierede luftangreb var voldsomme og blev gennemført af firemotorede bombefly, men de russiske angreb, der begyndte i februar 1945, blev gennemført af taktiske fly og forårsagede ikke samme typer ødelæggelser. Til gengæld blev de russiske luftangreb hyppigere og skiftede fra natangreb til dagangreb, hvor alt rullende trafik blev angrebet. Natten mellem den 5. og 6. marts Først på aftenen den 5. marts registrerede tyskerne løbende russiske indflyvninger mod Stettin i tidsrummet 19.00 til 01.00. Der deltog ialt omkring 50 russiske bombefly i disse angreb, der af tyskerne blev udlagt som 'Störangriffen'. Fra 20.10 til 20.40 blev Zlin angrebet af to andre russiske fly. Der blev ikke indsat natjagere mod de russiske fly. Ordenspolitiet i Stettin rapporterede om følgende skader: Stettin Auf Altdamm 10 Sprengbomben. Betroffen wurden: Amtsgericht, Heeresnebenzeugamt, personebahnhof, Güterbahnhof, Flugplatz (1 Schuppen abgebrannt). 35 Gefallene, 4 Schwer- und 42 Leichtverwundete. Treck an der Geifenhagener Strasse angegriffen. Anzahl der Gefallenen und Verwundeten steht noch nicht fest. Auf Finkenwalde 3 Spreng-, 4 Splitterbomben und 1 Brandbombe. leichter Gebäudeschaden. 2 Leichtverwundete. Höckendorf 1 Sprengbombe. 2 Häuer mittel, 2 Pferde getötet, 2 verletzt. Auf Autobahn bei Klütz Abwurf von Kleinstsplitterbomben auf Treck und Bordwaffenbeschuss. 7 Gefallene, 3 Leichtverwundete. 8 Pferde getötet. Augustwalde 1 Sprengbombe. 2 gefallene, 2 Schwerverletzte, 2 Leichtverwundete. Angrebet på Stettin blev senere på natten mellem klokken 04.32 og 05.31 fulgt op med yderligere angreb, hvor der blev kastet spræng- og brandbomber i bydelene Atldamm og Podejuch. -

THE CANADIAN BOMBER COMMAND SQUADRONS -Their Story in Their Words

www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca THE CANADIAN BOMBER COMMAND SQUADRONS -Their Story in Their Words- www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca Bomber Command Museum of Canada Nanton, Alberta, Canada www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca 429 Squadron Halifax and airmen at Leeming THE CANADIAN BOMBER COMMAND SQUADRONS -Their Story in Their Words- www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca Dave Birrell BOMBER COMMAND MUSEUM OF CANADA Copyright 2021 by Dave Birrell. All rights reserved. To reproduce anything in this book in any manner, permission must first be obtained from the Nanton Lancaster Society. Published by The Nanton Lancaster Society Box 1051 Nanton, Alberta, Canada; T0L 1R0 www.bombercommandmuseum.ca The Nanton Lancaster Society is a non-profit, volunteer-driven society which is registered with Revenue Canada as a charitable organization. Formed in 1986, the Society has the goals of honouring all those associated with Bomber Command and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. The Nanton Lancaster Society established and operates the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta which is located seventy-five kilometres south of Calgary. ISBN: 978-1-9990157-2-5 www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca 426 Squadron Halifax at Linton-on-Ouse CONTENTS Please note that the contents are arranged, for the most part, in chronological order. However, there are several sections of the book that relate to the history of Bomber Command in general. In these cases, the related documents may not necessarily be in chronological order. Introduction 7 1939, 1940 10 1941 12 1942 22 1943 39 1944 81 1945 137 www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca 431 Squadron Halifaxes at Croft 5 www.bombercommandmuseumarchives.ca 429 Squadron personnel at Leeming 6 INTRODUCTION There are at least two books that comprehensively tell the story of the Canadians who served with Bomber Command during the Second World War -notably ‘No Prouder Place -Canadians and the Bomber Command Experience’ by David Bashow and ‘Reap the Whirlwind’ by Spencer Dunmore.and William Carter. -

York in the Second World War

TEACHER PACK York in the Second World War A York Civic Trust/Explore York Libraries and Archives education pack TEACHER PACK TEACHER’S NOTE: HOW TO USE THIS WORKPACK This workpack has been designed to be easy to use and as flexible as possible. It comes in both a print and digital format. The digital pack - available at yorkcivictrust.co.uk/home/ education/ks2-education-packs/ - includes a greater range of case studies and authentic material. The idea is for you to use as much or as little of the pack as you like. It is aimed at Key Stage 2, but can be used for any classes/age groups that you think appropriate. There is a students’ version of the pack, and also a teachers’ version, which includes extra notes, suggestions and background information. The pack uses authentic materials, including photographs, documents, newspaper reports and case studies, to show how the Second World War affected the people of York. Questions are used to get your pupils thinking about these materials, about what life was like during the Second World War in York and for York people, and about how their own lives compare to the lives of the people whose stories are told here. The questions are open-ended, and designed to provoke interest, thought and debate. You can use these questions and the associated materials however you like: to spark class discussions or debates, to promote drama sessions, to stimulate children’s imaginations for a writing exercise, or as the starting point for research projects on local history. -

Lime & Ice Discovery Day at Sutton Bank

North York Moors National Park Education Service Lime & Ice Discovery Day at Sutton Bank Cross-curricular resources for teachers to extend learning before and after the visit Lime and Ice Discovery Day Walk Contents Cross-curricular resources for teachers to extend learning before and after the visit... Teachers’ Notes for the Discovery Day Walk . 3 1 Stop 1: Maps & Symbols . 4 1 Stop 2: Panoramic view and modern land use . 4 1 Stop 3: Lake Gormire and geomorphology . 5 1 Stop 4: The Cleveland Way . 6 1 Stop 5: The Yorkshire Gliding Club . 7 1 Stop 6: Iron Age Hill Fort . 8 1 Stop 7: Geology . 9 „ Activity: White Horses . 10 1 Stop 8: Trees . 11 1 Stop 9: Jurassic Sea . 11 1 Stop 10: Myths and Legends . 12 Suggestions for pre and post visit activities T Lesson Suggestions: Rocks & Fossils . 13 The Story of Mary Anning . 16 T Lesson Suggestions: Amy Johnson, Aviation & World War II . 18 The Story of Amy Johnson’s Flight to Australia . 22 T Lesson Suggestions: Myths & Legends . 26 The Story of White Mare Crag . 28 Templates for shadow puppets . 30 Story image (to colour-in) . 36 T Lesson Suggestions: Landscapes and J M W Turner . 37 North York Moors National Park Education Service The Moors National Park Centre, Danby, Whitby YO21 2NB Tel: 01439 770657 • Email: [email protected] North York Moors National Park Education Service Page 2 www.northyorkmoors.org.uk • Email: [email protected] • Tel: 01439 770657 Lime and Ice Discovery Day Walk Teachers’ Notes Introduction The Lime and Ice Discovery Day involves a fantastic circular walk from Sutton Bank National Park Centre, via the Yorkshire Gliding Club and the famous White Horse of Kilburn. -

LP02 Policies

Durham County EY LL A V S E E Stockton-on-Tees T Darlington M A H R Redcar and Cleveland U D Middlesbrough Stokesley (! Scarborough District Richmondshire District G IN M E E L o r s N P Northallerton M o (! r k Yo h r t Hambleton District o Bedale N (! Plan Area T O P C L I F F E Thirsk Ryedale District (! LIN TO N O N D O Harrogate District I S Easingwold U H (! S F E O R T H Legend Aerodrome Safeguarded Areas Plan Area Boundary Hambleton District Adjacent Districts National Park East Riding of © Crown copyright [and database rights] 2019 OS 100018555 York Yorkshire [ Aerodrome Safeguarded Areas Civic Centre, Stone Cross, Northallerton DL6 2UU Hambleton Local Plan; Policies Map July 2019 Telephone: 01609 779 977 Fax: 01609 767228 1:300,000 LEGEND: Allocations Boundaries Housing Allocations Plan Area Boundary Employment Allocations Hambleton District Boundary Mixed Use Allocations National Park Boundary Community Allocations Adjacent Local Authority Areas CI3 Local Green Space Development Policies EG2 Key Employment Sites EG2 General Employment Sites EG3 Town Centre Boundaries EG3 Primary Shopping Areas " " " EG4 Primary Shopping Frontage (Northallerton Only) " " " " " " " EG5 Pedestrian Gateways EG5 Pedestrian Improvements E2 Hazardous Installations E2 Hazardous Pipelines E2 Aerodrome Safeguarded Areas = = E2 Noise Zones = E3 Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINC) E3 Local Geological Sites E3 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) ÉÉÉE3 Local Nature Reserve (LNR) ÉÉÉE4 Green Infrastructure Corridors E5 Listed Buildings