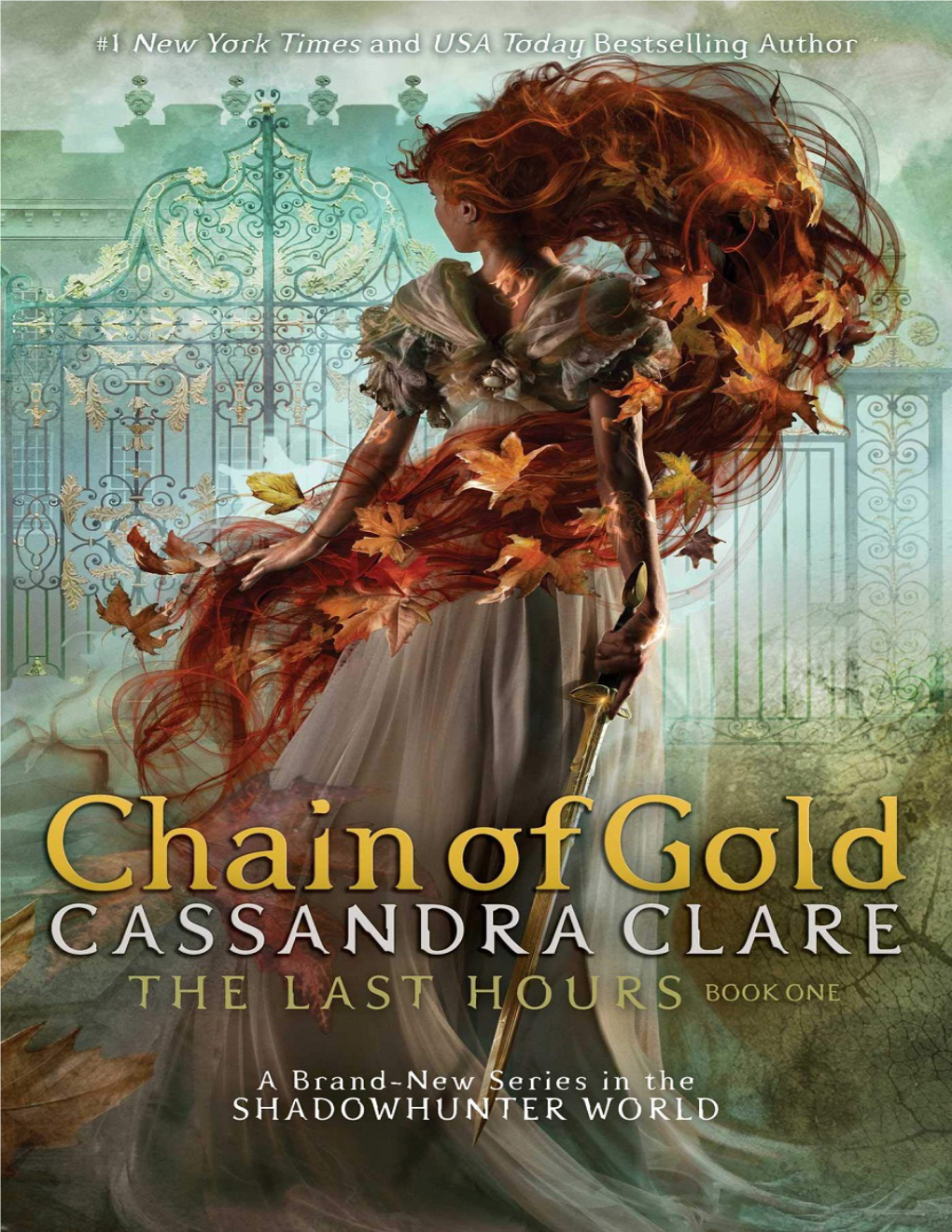

Chain of Gold Are Real: There Was a Devil Tavern on Fleet Street and Chancery, Where Samuel Pepys and Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angelology Angelology

Christian Angelology Angelology Introduction Why study Angels? They teach us about God As part of God’s creation, to study them is to study why God created the way he did. In looking at angels we can see God’s designs for his creation, which tells us something about God himself. They teach us about ourselves We share many similar qualities to the angels. We also have several differences due to them being spiritual beings. In looking at these similarities and differences we can learn more about the ways God created humanity. In looking at angels we can avoid “angelic fallacies” which attempt to turn men into angels. They are fascinating! Humans tend to be drawn to the supernatural. Spiritual beings such as angels hit something inside of us that desires to “return to Eden” in the sense of wanting to reconnect ourselves to the spiritual world. They are different, and different is interesting to us. Fr. J. Wesley Evans 1 Christian Angelology Angels in the Christian Worldview Traditional Societies/World of the Bible Post-Enlightenment Worldview Higher Reality God, gods, ultimate forces like karma and God (sometimes a “blind watchmaker”) fate [Religion - Private] Middle World Lesser spirits (Angels/Demons), [none] demigods, magic Earthly Reality Human social order and community, the Humanity, Animals, Birds, Plants, as natural world as a relational concept of individuals and as technical animals, plants, ect. classifications [Science - Public] -Adapted from Heibert, “The Flaw of the Excluded Middle” Existence of Angels Revelation: God has revealed their creation to us in scripture. Experience: People from across cultures and specifically Christians, have attested to the reality of spirits both good and bad. -

Haiirlfphtpr Hpralji for a Dinah ) Manchester — a City of Village Charm Ntaln- a Risk 30 Cents >D the Saturday, Nov

lostt: n.) (In (CC) <^Ns >ldfa- fendt. Ovaf' » ' An K>IV8S world. nvtta* »ii. (90 n Plc- :tantly leen- HaiirlfpHtPr HpralJi for a Dinah ) Manchester — A City of Village Charm ntaln- a risk 30 Cents >d the Saturday, Nov. 14.1987 y with n. W ill O 'Q ill ytallar lapra- Y> dfl* Tiny ‘FIRST STEF BY ORTEGA i in an tty by , John Contras I Evil' ito an f Den- criticize 1971. peace plan 1/ WASHINGTON (AP) — Nicara guan President Daniel Ortega on Friday laid out a detailed plan for reaching a cease-fire in three weeks with the Contras fighting his leftist government and a mediator agreed to carry the proposal to the U.S.-backed rebels. Ortega, indicating flexibility, called his plan “ a proposal, not an ultimatum." Contra leaders, react ing to news reports in Miami, criticized the plan and termed it "a proposal for anorderly surrender.” Ortega's 11-point plan was re ceived by Nicaraguan Cardinal Miguel Obando y Bravo, who agreed to act as a mediator between the two sides. The prelate planned to convey Ortega’s offer to the Contras and seek a response, opening cease-fire negotiations. The plan calls for a cease-fire to begin on Dec. 5 and for rebel troops inside Nicaragua to move to one of three cease-fire zones. The rebels would lay down their arms on Jan. 5 before independent observers, and then be granted amnesty. The plan specifies that Contras in the field are not to get any military supplies during the cease-fire, but would allow food, clothing and medical care to be provided them by a neutral international agency. -

The BG News December 4, 1998

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 12-4-1998 The BG News December 4, 1998 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News December 4, 1998" (1998). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6417. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6417 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. FRIDAY,The Dec. 4, 1998 A dailyBG Independent student News press Volume 85* No. 63 Speaker: HIGH: 57 ^k LOW: 50 'Sex is not an , emergency □ The safe sex discussion sponsored by Womyn for Womyn adressed many topics ■ The men's basketball of concern for women. team heads to Eastern Michigan Saturday. By mENE SHARON SCOTT The BG News Birth control methods, tools for safer sex and other issues ■ The women's were addressed at a "Safe Sex" basketball team is ready roundtable Thursday. The dis- for the Cougar BG News Photo/JASON SUGGS cussion was sponsored by Womyn for Womyn. shoot-out. People at Mark's Pub enjoy a drink Thursday. Below, John Tuylka, a senior psychology major takes a shot. Leah McGary, a certified fam- ily nurse practitioner from the Center for Choice, led the discus- Bars claim responsibility sion. ■ The men's swimming McGray emphasized the and diving teams are importance of using a birth con- BATTLE to curb binge drinking trol method. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Forgotten Tales a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts And

Forgotten Tales A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Lindsey A. Fischer April 2017 ©2017 Lindsey A. Fischer. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Forgotten Tales by LINDSEY A. FISCHER has been approved for the department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick O’Keeffe Assistant Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT FISCHER, LINDSEY A., M.A., April 2017, English Forgotten Tales Director of Thesis: Patrick O’Keeffe This collection of short stories retells fairy tales and myths to bring out themes of feminism, heroism, and forgotten voices. The critical introduction is an investigation into the history of fairy tale retellings, and how we can best write works that engage in a conversation with other stories. This intro also argues for a return to the oral tradition, which is how these original fairy tales and myths were told, in order to evoke the spontaneity of oral performance. This project is interested in story-telling, from our childhood to adulthood, as I create a new canon of fairy tales for grown-ups. 4 DEDICATION To my parents and brothers for their love and support, to E. for believing in me, and to the wonderful literary nerds in Ellis 8 for the inspiration 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project would never have happened without the advice and guidance of my adviser, Patrick O’Keeffe. Thank you for all the editing and encouragement. -

2011 Edition 1 the Morpheus Literary Publication

The Morpheus 2011 Edition 1 The Morpheus Literary Publication 2011 Edition Sponsored by the Heidelberg University English Department 2 About this publication Welcome to the Fall 2011 edition of the Morpheus, Heidelberg University’s student writing magazine. This year’s issue follows the precedents we established in 2007: 1) We publish the magazine electronically, which allows us to share the best writing at Heidelberg with a wide readership. 2) The magazine and the writing contest are managed by members of English 492, Senior Seminar in Writing, as an experiential learning component of that course. 3) The publication combines the winning entries of the Morpheus writing contest with the major writing projects from English 492. Please note that Morpheus staff members were eligible to submit entries for the writing contest; a faculty panel judged the entries, which had identifying information removed before judging took place. Staff members played no role in the judging of the contest entries. We hope you enjoy this year’s Morpheus! Dave Kimmel, Publisher 3 Morpheus Staff Emily Doseck................Editor in Chief Matt Echelberry.............Layout Editor Diana LoConti...............Contest Director Jackie Scheufl er.............Marketing Director Dr. Dave Kimmel............Faculty Advisor Special thanks to our faculty judges: Linda Chudzinski, Asst. Professor of Communication and Theater Arts; Director of Public Relations Major Dr. Doug Collar, Assoc. Professor of English & Integrated Studies; Assoc. Dean of the Honors Program Dr. Courtney DeMayo, Asst. Professor of History Dr. Robin Dever, Asst. Professor of Education Tom Newcomb, Professor of Criminal Justice and Political Science Courtney Ramsey, Adjunct Instructor of English Heather Surface, Adjunct Lecturer, Communication and Theater Arts; Advisor for the Kilikilik Dr. -

Share Prayer Was Given to Me Several Decades Ago by a Friend in the Old City of Jerusalem

Angels are messengers created and sent to us by God. They are like the laws of nature. They do not have free will as we do. Each angel has a specific task, often related to its name. The unique list of names of angels used in this share prayer was given to me several decades ago by a friend in the Old City of Jerusalem. He told me these are the names of angels mentioned in biblical literature. He was a scholar and a family man but subsequently fell from grace, becoming an addict and a beggar. The purpose and goal of this prayer is to end addiction, dishonesty, hunger, ignorance, illness, poverty and war – and to elevate mankind with awareness, connection, happiness, justice, morality, peace and tolerance. By Joshua Persky Let the Angels Loose (A Share Prayer) A Abir, demonstrate your might! Abirim, provide food, clothing, shelter and fuel for the poor! Achel, fix the world! Achiel, support the downtrodden! Achniel, teach my children tolerance! Adadiah, reveal the eternal! Adamoel, open the gates of paradise! Adeliel, sing celestial songs! Adiel, adorn my children with jewels! Adoel, reveal the potential of the universe! Adoniel, demonstrate I am the ruler of monarchs, presidents and prime ministers! Adramelech, save my children from fire! Adranel, demonstrate my majesty over all! Adriel, show mankind my splendor! Adrigon, renew my covenant with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, all the children of Israel and all humanity! Agariel, lift them to new heights! Agiel, help them distinguish between good and evil! Agrat bat Machlat, guide their desires -

"A Uniformity So Complete": Early Mormon Angelology

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Library Research Grants Harold B. Lee Library 2008 "A Uniformity So Complete": Early Mormon Angelology Benjamin Park Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/libraryrg_studentpub Part of the History of Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons The Library Student Research Grant program encourages outstanding student achievement in research, fosters information literacy, and stimulates original scholarship. BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Park, Benjamin, ""A Uniformity So Complete": Early Mormon Angelology" (2008). Library Research Grants. 26. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/libraryrg_studentpub/26 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Harold B. Lee Library at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Research Grants by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “A Uniformity So Complete”: Early Mormon Angelology Benjamin E. Park “A Uniformity so Complete” 2 “An angel of God never has wings,” boasted Joseph Smith in 1839, just as the Saints were establishing themselves in what would come to be known as Nauvoo, Illinois. The Mormon prophet then proceeded to explain to the gathered Saints that one could “discern” between true angelic beings, disembodied spirits, and devilish minions by a simple test of a handshake. He assured them that “the gift of discerning spirits will be given to the presiding Elder, pray for him…that he may have this gift[.]” 1 His statement, sandwiched between teachings on the importance of sacred ordinances and a reformulation of speaking in tongues, offer a succinct insight into Joseph Smith’s evolving understanding of angels and their relationship to human beings. -

St Frances Cabrini Catholic Church June 30, 2019

ST. FRANCES X. CABRINI CATHOLIC CHURCH THIRTEENTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME JUNE 30, 2019 St Frances Cabrini Catholic Church June 30, 2019 St. Frances X Cabrini Catholic Church Fr. Jim Cogan Administrator 12001 69th Street East, Parrish, FL 34219 Voice: (941)776-9097 Fax: (941)776-1307 Website: sfxcparrish.com E-mail: [email protected] Bulletin: [email protected] Parish Office Hours Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday 9:00am-3:00pm Closed Wednesday Emergencies day or night: (941) 201-9741 Bulletin submission deadline Monday 2 weeks prior to publication date Saturday Vigil 4:00pm Sunday 8:00am & Monday Tuesday Thursday Friday 10:30am 8:30am Baptism Mass First Sunday of Month Wednesday 7:00pm 10:30am Reconciliation Saturdays 3:00 pm Tuesday 9:00am— Blessed Virgin Mary Marriage Thursday 9:00am — St. Frances Cabrini Please contact the office at least 6 Novena Months prior to wedding date. Friday 9:00am –2:30pm - Adoration of Baptism the Blessed Sacrament Please contact Church office; Parent baptism instruction is required St. Frances Cabrini Catholic Church June 30, St Frances Cabrini Catholic Church June 30, 2019 Pray for those who have health issues, pain or worry. Sister Anne Marie; Maryann Allen;Barbara Atwell; Active Military Jerry Bennett; William Berrholder; Gerald Berry; Deborah Bifulco; Richard Blake;Matthew Bozarth; Sgt. Amy Cook; Sgt. Thomas Cook; SFC Kevin Buck Buchanan;Mary Ann Bueso; Ray Cade; Dave A. Correira; Sgt. John M. Danko, Jr; Lt. Pat- Cannon;Betty Carr;Terry Carter,Donna Lee Casto; rick Devito; Lt. Cmdr. Julie Dumais; P5 Kath- Andrew Chalfa;Ed Cherney;Deirdre Clark; Billy Clark; leen Foley; Maj. -

INVOCATION of ANGELS FIRST INVOCATION of CURSE of CURSES UPON the TRAITORS 6 December 2009 – 19 Kislev 5770

Invocation of Infinite Powers XXX Grand Council of Gnostics, 2005-2010 INVOCATION OF ANGELS FIRST INVOCATION OF CURSE OF CURSES UPON THE TRAITORS 6 December 2009 – 19 Kislev 5770 Akurian invocations are not parlor games! They are elements of extreme and irrevocable Forces and Energies. Invocations of Testimony are everlasting and without appeal. Authorized and Empowered Akurians use them sparingly, the wise and prudent study them diligently but do not use them at all, and fools destroy themselves and all those round them in their stupidity. There is nothing humorous or exciting about bringing an encroaching Hell of the First Magnitude down on your own head at your own hand. You have been warned. Do not EVER attempt to call upon the Four Great Horsemen at any time for any reason. They are an Elite Strike Unit Command with Direct Orders from The Most High, and will not heed any other. If they are called upon or invoked by anyone else, they are commanded to destroy all forces and energies relevant to that invocation whether blessing or curse, and to judge whosoever has invoked them as an abomination in The Sight of The Most High. Do not EVER attempt to call upon Akasha, Air, Fire, Water, Earth, Archangel Raphael, East Wind Apelotes, Servant Wind Eurea, Angel Bahaliel, Angel Sarabotes, Archangel Michael, South Wind Notae, Servant Wind Lipae, Angel Nafriel, Angel Jehuel, Archangel Gabriel, West Wind Zephyros, Servant Wind Skiron, Angel Aniel, Angel Hamal, Archangel Uriel, North Wind Boreas, Servant Wind Kaikias, Angel Beli, Angel Forlok, Archangel Remiel, Archangel Raguel, Archangel Zerachiel, Angel Ben Nez, Angel Pruel, Angel Druiel, or Angel Albim; nor attempt to invoke anything whatsoever until you are fully versed and practiced in associating with such Entities and handling such Powers, Forces and Energies. -

SEPTEMBER 29, 2019 MASS SCHEDULE WEEKEND Saturday

SEPTEMBER 29, 2019 MASS SCHEDULE WEEKEND Saturday ................................ 5:00 pm TWENTY-SIXTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Sunday .. 7:30 am, 9:00 am, 11:00 am ................................................ 5:00 pm WEEKDAY Mon, Tues, Wed ....................... 8:00 am at Franciscan Courts (815 S Westhaven) Thursdays & Fridays ............... 7:15 am ......................... at St. Raphael Church Radio Broadcast Mass 9:00 am every Sunday WOSH 1490 AM Reconciliation Saturday & Sunday .....3:30 pm-4:30 pm Tuesday ...................... 4:30 pm-5:30 pm Parish Office Hours Monday - Friday ...... 8:30 am - 4:30 pm Our Catholic School: Lourdes Academy ................. 426-3626 PASTORAL TEAM Pastor ............................... Fr. Tom Long Parochial Vicar ......... Fr. Matthew Rappl Pastoral Associate......... Betty Schwandt Deacons ......... Greg Grey, John Ingala, .......................................... Paul Vidmar This Weekend Parish Feast Day Weekend Prayer to St. Raphael This Week Glorious Archangel Raphael, who enters and serves before the Glory of the Lord: Holy Hour, Tuesday October 1 present to God the prayer of our need. 4:15pm As once you helped young Blessing of Pets, Thursday, October 3 Tobias on his travels, help us on our 4:45pm journey through life. Next Weekend Grant us healing of body, mind and spirit that we may New Member Information Weekend be faithful disciples of Jesus who pray, serve and generously share Coffee & Donuts after in response to the needs of the human family. Sunday Morning Masses A GREAT TRADITION: THE ARCHANGELS Based upon what we know from Scripture from Tobit 12:15; Revelation 1:4,20; 3:1; 8:2,6; and Isaiah 63:9, the Church has determined that there are Seven Archangels. -

Jason's Handy Jewish Magic Reference Guide

Jason's Handy Jewish Magic Reference Guide Part 0: Introduction If you're Jewish and you live in the U.S., chances are you grew up either Reform or Conservative. This means, more or less, that your rabbi likely left out all the coolest parts of Judaism. Not just kabbalah, but earlier mystical and magical traditions that most modern-day kabbalists might not even know about. Outside of academia, the existence of hundreds of ancient Jewish amulets and incantation bowls seems to be mostly unknown. I'd like to ask that you please pass this post along to any friends you think might want to know about it. Judaism needs to evolve as it always has, and this is my attempt to start a revolution from within. Tell your friends. As a result of our incomplete Jewish education, a lot of us have looked elsewhere. I certainly did. It took exploring many other traditions before I stumbled upon the parts of Judaism that really resonated for me. And when I've run into other Jews at pagan events, they're usually even more excited than I was to learn that there is indeed such a thing as Jewish folk magic. Rabbis have usually been against it, but not always; even the Talmud says that if an amulet has been shown to be effective for at least three people, Jews are allowed to carry it on Shabbat. No less a personage than the Baal Shem Tov made and sold amulets. But first, I'd like to address some of the most obvious questions about how Jewish magic can work at all.