Coins of Henry VIII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gold Coins of England, Arranged and Described

THE GOLD COINS OF ENGLAND. FMOTTIS PIECE. Edward die Coiiiessor. 16 TT^mund, Abp.of Yo Offa . King of Mercia ?.$.&&>. THE GOLD COINS OF ENGLAND AERANGED AND DESCRIBED BEING A SEQUEL TO MR. HAWKINS' SILVER COINS OF ENGLAND, BY HIS GRANDSON KOBEET LLOYD KENYON See p. 15. Principally from the collection in tlie British Museum, and also from coins and information communicated by J. Evans, Esq., President of the Numismatic. Society, and others. LONDON: BERNARD QUARITCH, 15 PICCADILLY MDCCCLXXXIV. : LONDON KV1AN AND <ON, PRINTERS, HART STREET. COVENT r,ARI>E\. 5 rubies, having a cross in the centre, and evidently intended to symbolize the Trinity. The workmanship is pronounced by Mr. Akerman to be doubtless anterior to the 8th century. Three of the coins are blanks, which seems to prove that the whole belonged to a moneyer. Nine are imitations of coins of Licinius, and one of Leo, Emperors of the East, 308 to 324, and 451 to 474, respectively. Five bear the names of French cities, Mettis, Marsallo, Parisius. Thirty- nine are of the seven types described in these pages. The remaining forty-three are of twenty-two different types, and all are in weight and general appearance similar to Merovingian ti-ientes. The average weight is 19*9 grains, and very few individual coins differ much from this. With respect to Abbo, whose name appears on this coin, the Vicomte de Ponton d'Ainecourt, who has paid great attention to the Merovingian series, has shown in the " Annuaire de la Societe Francaise de Numismatique " for 1873, that Abbo was a moneyer at Chalon-sur-Saone, pro- bably under Gontran, King of Burgundy, a.d. -

THE COINAGE of HENRY VII (Cont.)

THE COINAGE OF HENRY VII (cont.) w. J. w. POTTER and E. J. WINSTANLEY CHAPTER VIII. The Gold Money 1. The Angels and Angelets Type I. The first angels, like the first groats, are identical in style with those of the preceding reigns, having St. Michael with feathered wings and tunic and one foot on the ridged back of a substantial dragon with gaping jaws and coiled tail. There are the same two divisions of compound and single marks, but the latter are of great rarity and have unusual legends and stops and therefore are unlikely to be confused with the less rare earlier angels. Only three of the four compound marks on the groats are found on the type I angels, and they were very differently used. There are no halved lis and rose angels but on the other hand the halved sun and rose is one of the two chief marks found on both obverses and reverses. The lis on rose is also found on obverses and reverses, but the lis on sun and rose is known only on two altered obverses showing Richard Ill's sun and rose mark with superimposed lis (PI. IX, 1). We have examined twenty-one angels, representing practically all the known speci- mens and the summary of the marks on these is as follows: Obverses Reverses 1. Halved sun and rose (3 dies) 1. Halved sun and rose 8 2. Lis on rose 2 2. Lis on rose (3 dies) 1. Lis on rose 6 2. Halved sun and rose 1 3. -

Guide to the Collection of Irish Antiquities

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND ART, DUBLIN. GUIDE TO THE COLLECTION OF IRISH ANTIQUITIES. (ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY COLLECTION). ANGLO IRISH COINS. BY G COFFEY, B.A.X., M.R.I.A. " dtm; i, in : printed for his majesty's stationery office By CAHILL & CO., LTD., 40 Lower Ormond Quay. 1911 Price One Shilling. cj 35X5*. I CATALOGUE OF \ IRISH COINS In the Collection of the Royal Irish Academy. (National Museum, Dublin.) PART II. ANGLO-IRISH. JOHN DE CURCY.—Farthings struck by John De Curcy (Earl of Ulster, 1181) at Downpatrick and Carrickfergus. (See Dr. A. Smith's paper in the Numismatic Chronicle, N.S., Vol. III., p. 149). £ OBVERSE. REVERSE. 17. Staff between JiCRAGF, with mark of R and I. abbreviation. In inner circle a double cross pommee, with pellet in centre. Smith No. 10. 18. (Duplicate). Do. 19. Smith No. 11. 20. Smith No. 12. 21. (Duplicate). Type with name Goan D'Qurci on reverse. Obverse—PATRIC or PATRICII, a small cross before and at end of word. In inner circle a cross without staff. Reverse—GOAN D QVRCI. In inner circle a short double cross. (Legend collected from several coins). 1. ^PIT .... GOANDQU . (Irish or Saxon T.) Smith No. 13. 2. ^PATRIC . „ J<. ANDQURCI. Smith No. 14. 3. ^PATRIGV^ QURCI. Smith No. 15. 4. ^PA . IOJ< ^GOA . URCI. Smith No. 16. 5. Duplicate (?) of S. No. 6. ,, (broken). 7. Similar in type of ob- Legend unintelligible. In single verse. Legend unin- inner circle a cross ; telligible. resembles the type of the mascle farthings of John. Weight 2.7 grains ; probably a forgery of the time. -

The Milled Coinage of Elizabeth I

THE MILLED COINAGE OF ELIZABETH I D. G. BORDEN AND I. D. BROWN Introduction THIS paper describes a detailed study of the coins produced by Eloy Mestrelle's mill at the Tower of London between 1560 and 1571. We have used the information obtained from an examination of the coins to fill out the story of Eloy and his machinery that is given by the surviving documents. There have been a number of previous studies of this coinage. Peter Sanders was one of the first to provide a listing of the silver coins1 and more recently one of us (DGB) has published photographs of the principal types.2 The meagre documentary evidence relating to this coinage has been chronicled by Ruding,3 Symonds,4 Craig,5 Goldman6 and most recently by Challis.7 Hocking8 and Challis have given accounts of what little it known of the machinery used. This study first summarises the history of Mestrelle and his mill as found in the documents and then describes our die analysis based on an examination of enlarged photographs of 637 coins. We combine these two to propose a classification for the coinage in Appendix 2. Mestrelle and the Milled Coinage of Elizabeth I Queen Elizabeth I succeeded her sister Mary I as queen of England and Ireland in November 1558. On 31 December 1558 she signed a commission to Sir Edmund Peckham as high treasurer of the mint to produce gold and silver coins of the same denominations and standards as those of her sister, differing only in having her portrait and titles.9 The coins struck over the next eighteen months mostly never saw circulation because the large amount of base silver coin in circulation drove all the good coin into private savings or, worse, into the melting pot. -

A Handbook to the Coinage of Scotland

Gift of the for In ^ Nflmisutadcs Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/handbooktocoinagOOrobe A HANDBOOK TO THE COINAGE OF SCOTLAND. Interior of a Mint. From a French engraving of the reign of Louis XII. A HANDBOOK TO THE COINAGE OF SCOTLAND, GIVING A DESCRIPTION OF EVERY VARIETY ISSUED BY THE SCOTTISH MINT IN GOLD, SILVER, BILLON, AND COPPER, FROM ALEXANDER I. TO ANNE, With an Introductory Chapter on the Implements and Processes Employed. BY J. D. ROBERTSON, MEMBER OF THE NUMISMATIC SOCIETY OF LONDON. LONDON: GEORGE BELL ANI) SONS, YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN. 1878. CHISWICK PRESS C. WHITTINGHAM, TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE. TO C. W. KING, M.A., SENIOR FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, THIS LITTLE BOOK IS GRATEFULLY INSCRIBED. CONTENTS. PAGE Preface vii Introductory Chapter xi Table of Sovereigns, with dates, showing the metals in which each coined xxix Gold Coins I Silver Coins 33 Billon Coins 107 Copper Coins 123 Appendix 133 Mottoes on Scottish Coins translated 135 List of Mint Towns, with their principal forms of spelling . 138 Index 141 PREFACE. The following pages were originally designed for my own use alone, but the consideration that there must be many collectors and owners of coins who would gladly give more attention to this very interesting but somewhat involved branch of numismatics—were they not deterred by having no easily accessible information on the subject—has in- duced me to offer them to the public. My aim has been to provide a description of every coin issued by the Scottish Mint, with particulars as to weight, fineness, rarity, mint-marks, &c., gathered from the best authorities, whom many collectors would probably not have the opportunity of consulting, except in our large public libraries ; at the same time I trust that the information thus brought together may prove sufficient to refresh the memory of the practised numismatist on points of detail. -

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

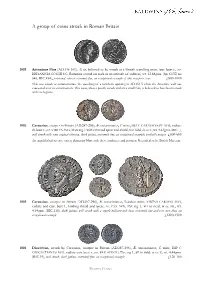

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

A REVIE\I\T of the COINAGE of CHARLE II

A REVIE\i\T OF THE COINAGE OF CHARLE II. By LIEUT.-COLONEL H. W. MORRIESON, F.s.A. PART I.--THE HAMMERED COINAGE . HARLES II ascended the throne on Maj 29th, I660, although his regnal years are reckoned from the death of • his father on January 30th, r648-9. On June 27th, r660, an' order was issued for the preparation of dies, puncheons, etc., for the making of gold and" silver coins, and on July 20th an indenture was entered into with Sir Ralph Freeman, Master of the Mint, which provided for the coinage of the same pieces and of the same value as those which had been coined in the time of his father. 1 The mint authorities were slow in getting to work, and on August roth an order was sent to the vVardens of the Mint directing the engraver, Thomas Simon, to prepare the dies. The King was in a hurry to get the money bearing his effigy issued, and reminders were sent to the Wardens on August r8th and September 2rst directing them to hasten the issue. This must have taken place before the end of the year, because the mint returns between July 20th and December 31st, r660,2 showed that 543 lbs. of silver, £r683 6s. in value, had been coined. These coins were considered by many to be amongst the finest of the English series. They fittingly represent the swan song of the Hammered Coinage, as the hammer was finally superseded by the mill and screw a short two years later. The denominations coined were the unite of twenty shillings, the double crown of ten shillings, and the crown of five shillings, in gold; and the half-crown, shilling, sixpence, half-groat, penny, 1 Ruding, II, p" 2. -

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Thursday 29 November 2007 10.00 am and 2.00 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Friday 23 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 26 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 27 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 28 November See below Or by previous appointment. Please note that viewing arrangements on Wednesday 28 November will be by appointment only, owing to restricted facilities. For convenience and comfort we strongly recommend that clients wishing to view multiple or bulky lots should plan to do so before 28 November. Catalogue no. 30 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Tom Eden, Paul Wood or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 172 (front); ex Lot 412 (back); Lot 745 (detail, inside front and back covers) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. -

British Coins

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ BRITISH COINS 567 Eadgar (959-975), cut Halfpenny, from small cross Penny of moneyer Heriger, 0.68g (S 1129), slight crack, toned, very fine; Aethelred II (978-1016), Penny, last small cross type, Bath mint, Aegelric, 1.15g (N 777; S 1154), large fragment missing at mint reading, good fine. (2) £200-300 with old collector’s tickets of pre-war vintage 568 Aethelred II (978-1016), Pennies (2), Bath mint, long -

The Medieval English Borough

THE MEDIEVAL ENGLISH BOROUGH STUDIES ON ITS ORIGINS AND CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY BY JAMES TAIT, D.LITT., LITT.D., F.B.A. Honorary Professor of the University MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 0 1936 MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS Published by the University of Manchester at THEUNIVERSITY PRESS 3 16-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13 PREFACE its sub-title indicates, this book makes no claim to be the long overdue history of the English borough in the Middle Ages. Just over a hundred years ago Mr. Serjeant Mere- wether and Mr. Stephens had The History of the Boroughs Municipal Corporations of the United Kingdom, in three volumes, ready to celebrate the sweeping away of the medieval system by the Municipal Corporation Act of 1835. It was hardly to be expected, however, that this feat of bookmaking, good as it was for its time, would prove definitive. It may seem more surprising that the centenary of that great change finds the gap still unfilled. For half a century Merewether and Stephens' work, sharing, as it did, the current exaggera- tion of early "democracy" in England, stood in the way. Such revision as was attempted followed a false trail and it was not until, in the last decade or so of the century, the researches of Gross, Maitland, Mary Bateson and others threw a fiood of new light upon early urban development in this country, that a fair prospect of a more adequate history of the English borough came in sight. Unfortunately, these hopes were indefinitely deferred by the early death of nearly all the leaders in these investigations. -

SCEATTAS: the NEGLECTED SILVER COINAGE of EARLY ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND- a COLLECTOR's PERSPECTIVE • PYTHAGORAS of SAMOS, CELATOR Lj Collection

T H E _ELATOlt Vol. 25, No. 11, NoveInber 2011 • SCEATTAS: THE NEGLECTED SILVER COINAGE OF EARLY ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND- A COLLECTOR'S PERSPECTIVE • PYTHAGORAS OF SAMOS, CELATOR lJ CollectIon Pantikapaion Gold Stater Kyrene Tetradrachm A Classical Masterpiece Syracuse Dekadrachm Head of Zeus Ammon An Icon of Ancient Greek Coinage A MagisteriJIl Specimen The Majestic Art ot Coins Over 600 Spectacular and Historically Important Greek Coins To be auctioned at the Waldorf Astoria, NEW YORK, 4 January 2012 A collection of sublime quality, extreme rarity, supreme artistic beauty and of exceptional historical importance. It has been over 20 years since such a comprehensive collection of high quality ancient Greek coins has been offered for sale in one auction. Contact Paul Hill ([email protected]) or Seth Freeman ([email protected]) for a free brochure Vol. 25. No. 11 The Celator'" Inside The Celato ~ ... November 20 11 Consecutive Issue No. 293 Incorporating Romall Coins (llId G il/lire FEATURES PublisherfEditor Kerry K. WcUerstrom [email protected] 6 Scealtas: The Neglected Silver Coinage of Early Anglo-Saxon England- Associate Editors A Collector's Perspective Robert L_ Black by Tony Abramson Michael R. Mehalick Page 6 22 Pythagoras of Samos, Celator for Back Issues from by John Francisco 1987 (0 May 1999 contact: Wayne Sayles DEPARTMENTS [email protected] Art: Parnell Nelson 2 Editor'S Note Coming Next Month Maps & Graphic Art: 4 Letters to the Editor Page 22 Kenny Grady 33 CE LTIC NEWS by Chris Rudd P.O. BoJ; 10607 34 People in the News lancaster, PA 17605 TeVFax: 717-656-8557 f:lro(j[~s in illlll1isntlltics (Ofllce HourI: Noon to 6PM) Art and the Market For FedEx & UPS deliveries: 35 Kerry K. -

Britain and the Pound Sterling

Britain and the Pound Sterling! !by Robert Schneebeli! ! Weight of metal, number of coins For the first 400 years of the Christian era, England was a Roman province, «Britannia». The word «pound» comes from Latin: the Roman pondus was divided into twelve unciae, which in turn gives us our English word “ounce”. In weighing precious metals the pound Troy of 12 ounces is used, 373 grams in metric units. In France, instead of pondus, the Latin word libra, weighing- scales, was used instead, so that «pound» in French is livre. That is why, when we weigh meat, for example, and want to write seven pounds, we write 7 lb., as if we were saying librae instead of pounds. And if we’re talking about pounds in the monetary sense, we also use a sign that reminds us of the Latin libra – the pounds sign, £, is actually only a stylised letter L. In the 8th century, in the age of King Offa in England or of Charlemagne in Europe, when the English currency began to be regulated, it was not the pound that was important, but the penny. The origin of the word «penny», and how it came to mean a coin, is obscure. A penny was a small silver coin – for coinage purposes silver was more important than gold (for example, the French word for money, argent, comes from argentum, the Latin for silver). Alfred the Great, the most famous of the Anglo-Saxon kings, fixed the weight of the silver penny and had pennies minted with a clear design.