Britain and the Pound Sterling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thirteenth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm

Thirteenth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm WORLD BANKNOTES part 3353* 3355* Dominican Republic, Banco Central de la Republica Dominican Republic, Banco Central de la Republica Dominica, specimen five pesos oro, 1993, 000000, Dominica, specimen set of fi ve, includes fi fty, one hundred, ESPECIMEN/MUESTRA SIN VALOR diagonally in black five hundred, one thousand and two thousand pesos on fronts and backs, individually numbered 111, 112, 238 dominicanos, 2012, GE 000000, ZQ 000000, KV 000000, and 299 in black bottom left margins on fronts (P.143s). FE 000000 and CR 000000, ESPECIMEN/MUESTRA SIN Uncirculated, the fi rst illustrated. (4) VALOR diagonally in black on fronts and backs, double $100 punch hole cancellation at bottom left, each numbered 0799 in red bottom left margin on front (P.183cs, 184cs, 186cs, 3354 187cs, 188s). Uncirculated. (5) Dominican Republic, Banco Central de la Republica $180 Dominicana, two hundred pesos oro, 2007, prefi xes AA (2) and CA (3) (P.178). Uncirculated. (5) 3356 $80 East Caribbean States, Eastern Carribean Central Bank, fi ve dollars (1994), St Kitts, C527206/9K four consecutive (P.31k) (4); St Lucia, H986011/4L four consecutive (P.31l) (4); Montserrat, A258351/4M four consecutive (P.31m) (4); Anguilla, A235615/8U four consecutive (P.31u) (4); also (2000), Montserrat, A707460/3M four consecutive (P.37m) (4). Uncirculated. (20) $500 3357 Egypt, Central Bank of Egypt, fi fty pounds, 2001 (P.66a) four consecutive notes. Uncirculated. (4) $50 3358* Falkland Islands, The Government of the Falkland Islands, George V, fi ve pounds uniface printer's proof on card, 1st February 1921, with printer's notations at right (cfP.3). -

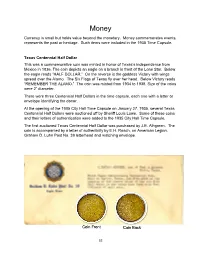

1935 Time Capsule Part 3

Money Currency is small but holds value beyond the monetary. Money commemorates events, represents the past or heritage. Such items were included in the 1935 Time Capsule. Texas Centennial Half Dollar This was a commemorative coin was minted in honor of Texas’s independence from Mexico in 1836. The coin depicts an eagle on a branch in front of the Lone Star. Below the eagle reads “HALF DOLLAR.” On the reverse is the goddess Victory with wings spread over the Alamo. The Six Flags of Texas fly over her head. Below Victory reads “REMEMBER THE ALAMO.” The coin was minted from 1934 to 1938. Size of the coins were 2” diameter. There were three Centennial Half Dollars in the time capsule, each one with a letter or envelope identifying the donor. At the opening of the 1905 City Hall Time Capsule on January 27, 1935, several Texas Centennial Half Dollars were auctioned off by Sheriff Louis Lowe. Some of these coins and their letters of authentication were added to the 1935 City Hall Time Capsule. The first auctioned Texas Centennial Half Dollar was purchased by J.E. Alhgreen. The coin is accompanied by a letter of authenticity by E.H. Roach, on American Legion, Graham D. Luhn Post No. 39 letterhead and matching envelope. Coin Front Coin Back 32 Letter Front 33 Letter Back 34 The second Texas Centennial Half Dollar was purchased at the same auction by E.E. Rummel. Shown below are the paperwork establishing the authenticity of the purchase by E.H. Roach, on American Legion, Graham D. -

Britain's Cartwheel Coinage of 1797

Britain's Cartwheel Coinage of 1797 by George Manz You've probably heard these words and names before: Cartwheel, Soho, Matthew Boulton, and James Watt. But did you know how instrumental they were in accelerating the Industrial Revolution? Like the strands of a rope, the history of Britain's 1797 Cartwheel coinage is intertwined with the Industrial Revolution. And that change in the method of producing goods for market is intermeshed with the Soho Mint and its owners, Matthew Boulton and James Watt. We begin this story in Birmingham, England in 1759 when Matthew Boulton Jr., now in his early 30s, inherited his father's toy business which manufactured many items, including buttons. Later that year, or possibly the following year, young Matthew Boulton's first wife Mary died. "While personally devastating," Richard Doty writes in his marvelous book, The Soho Mint & the Industrialization of Money, "the deaths of his father and his first wife helped make Soho possible. His father had left the toy business to him, while the estate of his wife, who was a daughter and co-heiress of the wealthy Luke Robinson of Litchfield, added to his growing resources." Doty, the curator of numismatics for the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., notes that Boulton eventually went on to wed Mary's sister Anne; Luke Robinson's other daughter and now sole heir to the family fortune. Boulton built a mill which he called Soho Manufactory, named for a place already called Soho, near Birmingham. The mill was erected beside Hockley Brook, which provided the water- power to help power the new factory. -

Guide to the Collection of Irish Antiquities

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND ART, DUBLIN. GUIDE TO THE COLLECTION OF IRISH ANTIQUITIES. (ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY COLLECTION). ANGLO IRISH COINS. BY G COFFEY, B.A.X., M.R.I.A. " dtm; i, in : printed for his majesty's stationery office By CAHILL & CO., LTD., 40 Lower Ormond Quay. 1911 Price One Shilling. cj 35X5*. I CATALOGUE OF \ IRISH COINS In the Collection of the Royal Irish Academy. (National Museum, Dublin.) PART II. ANGLO-IRISH. JOHN DE CURCY.—Farthings struck by John De Curcy (Earl of Ulster, 1181) at Downpatrick and Carrickfergus. (See Dr. A. Smith's paper in the Numismatic Chronicle, N.S., Vol. III., p. 149). £ OBVERSE. REVERSE. 17. Staff between JiCRAGF, with mark of R and I. abbreviation. In inner circle a double cross pommee, with pellet in centre. Smith No. 10. 18. (Duplicate). Do. 19. Smith No. 11. 20. Smith No. 12. 21. (Duplicate). Type with name Goan D'Qurci on reverse. Obverse—PATRIC or PATRICII, a small cross before and at end of word. In inner circle a cross without staff. Reverse—GOAN D QVRCI. In inner circle a short double cross. (Legend collected from several coins). 1. ^PIT .... GOANDQU . (Irish or Saxon T.) Smith No. 13. 2. ^PATRIC . „ J<. ANDQURCI. Smith No. 14. 3. ^PATRIGV^ QURCI. Smith No. 15. 4. ^PA . IOJ< ^GOA . URCI. Smith No. 16. 5. Duplicate (?) of S. No. 6. ,, (broken). 7. Similar in type of ob- Legend unintelligible. In single verse. Legend unin- inner circle a cross ; telligible. resembles the type of the mascle farthings of John. Weight 2.7 grains ; probably a forgery of the time. -

Penny 1 - 64 5 Penny 65 - 166 15 Threepence 167 - 221 32 4 1914 Halfpenny (Obv 1/Rev A)

LOT 8 LOT 15 LOT 100 LOT 180 Stunning! That was my first impression of this fantastic collection. So many superb grade coins, superb strikes, wonderful old tone, beautiful eye appeal, in a word - sexy… the list of superlatives goes on. Handling a Complete Collection such as the Benchmark Collection is a once in a lifetime opportunity, and we are proud to present this magnificent collection, in conjunction with Strand Coins (who have compiled it over many years with the current owner). We have included many notes and comments by Mark Duff of Strand Coins due to his intimate knowledge of every coin and it’s provenance, as well as a comprehensive, never before released illustrated “Key” to each and every coin Obverse and Reverse die type. As such, the catalogue, the information and images it contains will truly become a Benchmark in their own right. The quality of the George V coins right across the board is simply unbeatable, the Florins contain so many breathtaking coins, the Silver issues are all struck up, the Copper has many amazing coins, and most of the “Varieties” are amongst the finest, if not the finest known. The grading by NGC is very even across every lot, and if anything, is sometimes conservative given the genuine superb quality of the collection. We are proud to offer this complete “Benchmark” collection, the likes of which may not be seen on the market ever again. Viewing In Sydney: Monday 5th to Saturday 10th January 2015, Strand Coins, Ground Floor Shop 1c Strand Arcade, 412-414 George St, Sydney NSW 2000 10am to 5pm. -

147 Chapter 5 South Africa's Experience with Inflation: A

147 CHAPTER 5 SOUTH AFRICA’S EXPERIENCE WITH INFLATION: A CENTRAL BANK PERSPECTIVE 5.1 Introduction Although a country’s experience with inflation can be reviewed from different perspectives (e.g. the government, the statistical agency responsible for recording inflation, producers, consumers or savers), this chapter reviews South Africa’s experience with inflation from the perspective of the SA Reserve Bank. The SA Reserve Bank was chosen because this study focuses on inflation from a monetary perspective. Reliable inflation data for South Africa are published as far back as 192153, co-inciding with the establishment of the SA Reserve Bank, although rudimentary data on price levels are available as far back as 1895. South Africa’s problems with accelerating inflation since the 1970s are well documented (see for instance De Kock, 1981; De Kock, 1984; Republiek van Suid-Afrika, 1985; Rupert, 1974a; Rupert, 1974b; or Stals, 1989), but various parts (or regions) of what constitutes today the Republic of South Africa have experienced problems with inflation, rising prices or currency depreciation well before 1921. The first example of early inflation in South Africa was caused by currency depreciation. At the time of the second British annexation of the Cape in 1806, the Dutch riksdaalder (“riksdollar”) served as the major local currency in circulation. During the tenure of Caledon, Governor of the Cape Colony from 1807 to 1811, and Cradock, Governor from 1811 to 1814, riksdollar notes in circulation were increased by nearly 50 per cent (Engelbrecht, 1987: 29). As could be expected under circumstances of increasing currency in circulation, the value of the riksdollar in comparison to the British pound sterling and in terms of its purchasing power declined from 4 shillings in 1806 to 1 shilling and 5½ pennies in 1825 (or 53 Tables A1 to C1 in Appendices A to C highlight South Africa’s experience with inflation, as measured by changes in the CPI since 1921. -

USA Metric System History Pat Naughtin 2009 Without the Influence of Great Leaders from the USA There Would Be No Metric System

USA metric system history Pat Naughtin 2009 Without the influence of great leaders from the USA there would be no metric system. Since many in the USA do not believe this statement, let me repeat it in a different way. It is my belief that without the influence of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington, the metric system would not have developed in France in the 1780s and 1790s. The contribution made by these three great world leaders arose firstly from their cooperation in developing and implementing the idea of a decimal currency for the USA. The idea was that all money could be subdivided by decimal fractions so that money calculations would then be little more difficult than any normal whole number calculation. In 1782, Thomas Jefferson argued for a decimal currency system with 100 cents in a dollar. Less well known, he also argued for 1000 mils in a dollar. Jefferson reasoned that dividing America's First Silver Dollar decimally was the simplest way of doing this, and that a decimal system based on America's First Silver Dollar should be adopted as standard for the USA. The idea of using decimal fractions with decimal numbers was not new – even in the 1780s. Thomas Jefferson had studied 'Disme: the art of tenths' by Simon Stevin in which the use of decimals for all activities was actively promoted. Stevin proposed decimal fractions and their decimal arithmetic for: ... stargazers, surveyors, carpet-makers, wine-gaugers, mint-masters and all kind of merchants. Clearly Simon Stevin had in mind the use of decimal methods for all human activities and it is likely that this thought inspired Thomas Jefferson to propose not only a decimal currency for the USA but also a whole decimal method for weights and measures. -

INFORMATION BULLETIN #50 SALES TAX JULY 2017 (Replaces Information Bulletin #50 Dated July 2016) Effective Date: July 1, 2016 (Retroactive)

INFORMATION BULLETIN #50 SALES TAX JULY 2017 (Replaces Information Bulletin #50 dated July 2016) Effective Date: July 1, 2016 (Retroactive) SUBJECT: Sales of Coins, Bullion, or Legal Tender REFERENCE: IC 6-2.5-3-5; IC 6-2.5-4-1; 45 IAC 2.2-4-1; IC 6-2.5-5-47 DISCLAIMER: Information bulletins are intended to provide nontechnical assistance to the general public. Every attempt is made to provide information that is consistent with the appropriate statutes, rules, and court decisions. Any information that is inconsistent with the law, regulations, or court decisions is not binding on the department or the taxpayer. Therefore, the information provided herein should serve only as a foundation for further investigation and study of the current law and procedures related to the subject matter covered herein. SUMMARY OF CHANGES Other than nonsubstantive, technical changes, this bulletin is revised to clarify that sales tax exemption for certain coins, bullion, or legal tender applies to coins, bullion, or legal tender that would be allowable investments in individual retirement accounts or individually-directed accounts, even if such coins, bullion, or legal tender was not actually held in such accounts. INTRODUCTION In general, an excise tax known as the state gross retail (“sales”) tax is imposed on sales of tangible personal property made in Indiana. However, transactions involving the sale of or the lease or rental of storage for certain coins, bullion, or legal tender are exempt from sales tax. Transactions involving the sale of coins or bullion are exempt from sales tax if the coins or bullion are permitted investments by an individual retirement account (“IRA”) or by an individually-directed account (“IDA”) under 26 U.S.C. -

The Ship Halfpenny (1937 – 1970)

THE SHIP HALFPENNY (1937 – 1970) This Brushwood Coin Note is the first in the series and explores one of our favourite coins - the ‘ship’ halfpenny - the reverse was inspired by Sir Francis Drake’s “Golden Hind.” The design was created by Mr T H Paget OBE in 1937, and you will find his initials (HP) in the field below the stern on each coin. The ship halfpenny design was issued into circulation between the years of 1937 and 1967, eventually being demonetised on 31 July 1969. However, a final ship halfpenny was minted retrospectively for 1970, but only issued in proof sets of that year. In 1971 the much smaller and less popular “new half pence” was then introduced as part of the new decimal coinage. The original coin was not often called a 'half penny', neither was the plural said as 'half pence'. The usual pronunciation sounded like 'hayp-knee' referring to a single coin or 'hay- punce' in the plural, as for example in 'three halfpence'. Manufactured in bronze, with a diameter of 25.4 mm (one inch) and a weight of about 5.7g, there were 480 halfpennies in a pound (£1). Before the reign of Edward I the halfpenny had been generally obtained by cutting pennies in half and was at that time, like the penny, originally minted in silver. Copper half pennies made their first appearance in 1672, and in turn were replaced in 1860 by the bronze version, of which the ship halfpenny is the final example of pre-decimal coinage. KING EDWARD VIII On the accession of Edward VIII the new reverse design of the bronze halfpenny was first produced showing the Golden Hind, the ship used by Sir Francis Drake the noted Elizabethan sailor. -

List of Business 6Th November 2019

ORDERS APPROVED AND BUSINESS TRANSACTED AT THE PRIVY COUNCIL HELD BY THE QUEEN AT BUCKINGHAM PALACE ON 6TH NOVEMBER 2019 COUNSELLORS PRESENT The Rt Hon Jacob Rees-Mogg (Lord President) The Rt Hon Robert Buckland QC The Rt Hon Alister Jack The Rt Hon Alok Sharma Privy The Rt Hon The Lord Ashton of Hyde, the Rt Hon Conor Burns, Counsellors the Rt Hon Zac Goldsmith, the Rt Hon Alec Shelbrooke, the Rt Hon Christopher Skidmore and the Rt Hon Rishi Sunak were sworn as Members of Her Majesty’s Most Honourable Privy Council. Order appointing Jesse Norman a Member of Her Majesty’s Most Honourable Privy Council. Proclamations Proclamation declaring the calling of a new Parliament on the 17th of December 2019 and an Order directing the Lord Chancellor to cause the Great Seal to be affixed to the Proclamation. Six Proclamations:— 1. determining the specifications and designs for a new series of seven thousand pound, two thousand pound, one thousand pound and five hundred pound gold coins; and a new series of one thousand pound, five hundred pound and ten pound silver coins; 2. determining the specifications and designs for a new series of one thousand pound, five hundred pound, one hundred pound and twenty-five pound gold coins; a new series of five hundred pound, ten pound, five pound and two pound standard silver coins; a new series of ten pound silver piedfort coins; a new series of one hundred pound platinum coins; and a new series of five pound cupro-nickel coins; 3. determining the specifications and designs for a new series of five hundred pound, two hundred pound, one hundred pound, fifty pound, twenty-five pound, ten pound, one pound and fifty pence gold coins; a new series of five hundred pound, ten pound, two pound, one pound, fifty pence, twenty pence, ten pence and five pence silver coins; and a new series of twenty-five pound platinum coins; 4. -

Elimination of the One Cent Coin the Bahamian One Cent Coin Or the “Penny” Is Being Phased

Central Bank of The Bahamas FAQS: Elimination of the One Cent Coin The Bahamian one cent coin or the “penny” is being phased out of circulation. After the end of 2020 it will no longer be legal tender in The Bahamas. It is further proposed that circulation of or acceptance of US pennies will cease at the same time as the Bahamian coin. Why is the one cent coin or penny being phased out? Rising cost of production relative to face value Increased accumulation and non-use of pennies The significant handling cost of pennies When will the Central Bank stop distributing the penny? The Central Bank will stop distributing pennies to commercial banks on the 31st January 2020. Financial institutions will no longer be providing new supplies of the coins to consumers and businesses. Are businesses required to accept pennies after the end of January 2020? NO. Businesses may decide to stop accepting pennies anytime after the end of January 2020. Can businesses continue to accept pennies after the end of December 2020? NO. Businesses will not be able to accept payment or give change in one cent pieces after the end of December 2020. All cash payments will to be rounded to the nearest five cents. How will cash amounts be rounded? Business must round the total amount due to the nearest five cents If your total bill is $9.42 or $9.41. The nearest five cents to either of these would be $9.40 If your total bill is $9.43 or $9.44, the nearest five cents to either of these would be $9.45. -

A History of the Canadian Dollar 53 Royal Bank of Canada, $5, 1943 in 1944, Banks Were Prohibited from Issuing Their Own Notes

Canada under Fixed Exchange Rates and Exchange Controls (1939-50) Bank of Canada, $2, 1937 The 1937 issue differed considerably in design from its 1935 counterpart. The portrait of King George VI appeared in the centre of all but two denominations. The colour of the $2 note in this issue was changed to terra cotta from blue to avoid confusion with the green $1 notes. This was the Bank’s first issue to include French and English text on the same note. The war years (1939-45) and foreign exchange reserves. The Board was responsible to the minister of finance, and its Exchange controls were introduced in chairman was the Governor of the Bank of Canada through an Order-in-Council passed on Canada. Day-to-day operations of the FECB were 15 September 1939 and took effect the following carried out mainly by Bank of Canada staff. day, under the authority of the War Measures Act.70 The Foreign Exchange Control Order established a The Foreign Exchange Control Order legal framework for the control of foreign authorized the FECB to fix, subject to ministerial exchange transactions, and the Foreign Exchange approval, the exchange rate of the Canadian dollar Control Board (FECB) began operations on vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar and the pound sterling. 16 September.71 The Exchange Fund Account was Accordingly, the FECB fixed the Canadian-dollar activated at the same time to hold Canada’s gold value of the U.S. dollar at Can$1.10 (US$0.9091) 70. Parliament did not, in fact, have an opportunity to vote on exchange controls until after the war.