A New Privy Mark on a Robert II Groat Prefigured on False Coins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Collection of Irish Antiquities

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND ART, DUBLIN. GUIDE TO THE COLLECTION OF IRISH ANTIQUITIES. (ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY COLLECTION). ANGLO IRISH COINS. BY G COFFEY, B.A.X., M.R.I.A. " dtm; i, in : printed for his majesty's stationery office By CAHILL & CO., LTD., 40 Lower Ormond Quay. 1911 Price One Shilling. cj 35X5*. I CATALOGUE OF \ IRISH COINS In the Collection of the Royal Irish Academy. (National Museum, Dublin.) PART II. ANGLO-IRISH. JOHN DE CURCY.—Farthings struck by John De Curcy (Earl of Ulster, 1181) at Downpatrick and Carrickfergus. (See Dr. A. Smith's paper in the Numismatic Chronicle, N.S., Vol. III., p. 149). £ OBVERSE. REVERSE. 17. Staff between JiCRAGF, with mark of R and I. abbreviation. In inner circle a double cross pommee, with pellet in centre. Smith No. 10. 18. (Duplicate). Do. 19. Smith No. 11. 20. Smith No. 12. 21. (Duplicate). Type with name Goan D'Qurci on reverse. Obverse—PATRIC or PATRICII, a small cross before and at end of word. In inner circle a cross without staff. Reverse—GOAN D QVRCI. In inner circle a short double cross. (Legend collected from several coins). 1. ^PIT .... GOANDQU . (Irish or Saxon T.) Smith No. 13. 2. ^PATRIC . „ J<. ANDQURCI. Smith No. 14. 3. ^PATRIGV^ QURCI. Smith No. 15. 4. ^PA . IOJ< ^GOA . URCI. Smith No. 16. 5. Duplicate (?) of S. No. 6. ,, (broken). 7. Similar in type of ob- Legend unintelligible. In single verse. Legend unin- inner circle a cross ; telligible. resembles the type of the mascle farthings of John. Weight 2.7 grains ; probably a forgery of the time. -

A Handbook to the Coinage of Scotland

Gift of the for In ^ Nflmisutadcs Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/handbooktocoinagOOrobe A HANDBOOK TO THE COINAGE OF SCOTLAND. Interior of a Mint. From a French engraving of the reign of Louis XII. A HANDBOOK TO THE COINAGE OF SCOTLAND, GIVING A DESCRIPTION OF EVERY VARIETY ISSUED BY THE SCOTTISH MINT IN GOLD, SILVER, BILLON, AND COPPER, FROM ALEXANDER I. TO ANNE, With an Introductory Chapter on the Implements and Processes Employed. BY J. D. ROBERTSON, MEMBER OF THE NUMISMATIC SOCIETY OF LONDON. LONDON: GEORGE BELL ANI) SONS, YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN. 1878. CHISWICK PRESS C. WHITTINGHAM, TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE. TO C. W. KING, M.A., SENIOR FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, THIS LITTLE BOOK IS GRATEFULLY INSCRIBED. CONTENTS. PAGE Preface vii Introductory Chapter xi Table of Sovereigns, with dates, showing the metals in which each coined xxix Gold Coins I Silver Coins 33 Billon Coins 107 Copper Coins 123 Appendix 133 Mottoes on Scottish Coins translated 135 List of Mint Towns, with their principal forms of spelling . 138 Index 141 PREFACE. The following pages were originally designed for my own use alone, but the consideration that there must be many collectors and owners of coins who would gladly give more attention to this very interesting but somewhat involved branch of numismatics—were they not deterred by having no easily accessible information on the subject—has in- duced me to offer them to the public. My aim has been to provide a description of every coin issued by the Scottish Mint, with particulars as to weight, fineness, rarity, mint-marks, &c., gathered from the best authorities, whom many collectors would probably not have the opportunity of consulting, except in our large public libraries ; at the same time I trust that the information thus brought together may prove sufficient to refresh the memory of the practised numismatist on points of detail. -

A REVIE\I\T of the COINAGE of CHARLE II

A REVIE\i\T OF THE COINAGE OF CHARLE II. By LIEUT.-COLONEL H. W. MORRIESON, F.s.A. PART I.--THE HAMMERED COINAGE . HARLES II ascended the throne on Maj 29th, I660, although his regnal years are reckoned from the death of • his father on January 30th, r648-9. On June 27th, r660, an' order was issued for the preparation of dies, puncheons, etc., for the making of gold and" silver coins, and on July 20th an indenture was entered into with Sir Ralph Freeman, Master of the Mint, which provided for the coinage of the same pieces and of the same value as those which had been coined in the time of his father. 1 The mint authorities were slow in getting to work, and on August roth an order was sent to the vVardens of the Mint directing the engraver, Thomas Simon, to prepare the dies. The King was in a hurry to get the money bearing his effigy issued, and reminders were sent to the Wardens on August r8th and September 2rst directing them to hasten the issue. This must have taken place before the end of the year, because the mint returns between July 20th and December 31st, r660,2 showed that 543 lbs. of silver, £r683 6s. in value, had been coined. These coins were considered by many to be amongst the finest of the English series. They fittingly represent the swan song of the Hammered Coinage, as the hammer was finally superseded by the mill and screw a short two years later. The denominations coined were the unite of twenty shillings, the double crown of ten shillings, and the crown of five shillings, in gold; and the half-crown, shilling, sixpence, half-groat, penny, 1 Ruding, II, p" 2. -

Britain and the Pound Sterling

Britain and the Pound Sterling! !by Robert Schneebeli! ! Weight of metal, number of coins For the first 400 years of the Christian era, England was a Roman province, «Britannia». The word «pound» comes from Latin: the Roman pondus was divided into twelve unciae, which in turn gives us our English word “ounce”. In weighing precious metals the pound Troy of 12 ounces is used, 373 grams in metric units. In France, instead of pondus, the Latin word libra, weighing- scales, was used instead, so that «pound» in French is livre. That is why, when we weigh meat, for example, and want to write seven pounds, we write 7 lb., as if we were saying librae instead of pounds. And if we’re talking about pounds in the monetary sense, we also use a sign that reminds us of the Latin libra – the pounds sign, £, is actually only a stylised letter L. In the 8th century, in the age of King Offa in England or of Charlemagne in Europe, when the English currency began to be regulated, it was not the pound that was important, but the penny. The origin of the word «penny», and how it came to mean a coin, is obscure. A penny was a small silver coin – for coinage purposes silver was more important than gold (for example, the French word for money, argent, comes from argentum, the Latin for silver). Alfred the Great, the most famous of the Anglo-Saxon kings, fixed the weight of the silver penny and had pennies minted with a clear design. -

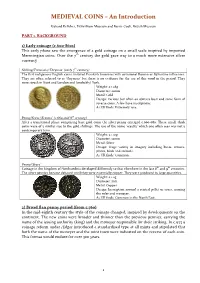

MEDIEVAL COINS – an Introduction

MEDIEVAL COINS – An Introduction Richard Kelleher, Fitzwilliam Museum and Barrie Cook, British Museum PART 1. BACKGROUND 1) Early coinage (c.600-860s) This early phase saw the emergence of a gold coinage on a small scale inspired by imported Merovingian coins. Over the 7 th century the gold gave way to a much more extensive silver currency Shilling/Tremissis/‘Thrymsa’ (early 7 th century) The first indigenous English coins imitated Frankish tremisses with occasional Roman or Byzantine influences. They are often referred to as ‘thrymsas’ but there is no evidence for the use of this word in the period. They were struck in Kent and London and (probably) York. Weight: c.1.28g Diameter: 12mm Metal: Gold Design: various but often an obverse bust and some form of reverse cross. A few have inscriptions. As UK finds: Extremely rare. Penny/Sceat/‘Sceatta’ (c.660-mid 8 th century) After a transitional phase comprising base gold coins the silver penny emerged c.660-680. These small, thick coins were of a similar size to the gold shillings. The use of the name ‘sceatta’ which one often sees was not a contemporary term. Weight: c.1.10g Diameter: 12mm Metal: Silver Design: Huge variety in imagery including busts, crosses, plants, birds and animals. As UK finds: Common. Penny/‘Styca’ Coinage in the kingdom of Northumbria developed differently to that elsewhere in the late 8 th and 9 th centuries. The silver pennies became debased until they were essentially copper. They were produced in large quantities. Weight: c.1.2g Diameter: mm Metal: Copper Design: Inscription around a central pellet or cross, naming the ruler and moneyer. -

Currency During the Tenure of the British

BRITISH COINS IN THE BEGINNING OF THE 19TH CENTURY CURRENCY DURING THE TENURE OF THE BRITISH In 1800, Malta passed under the control of Great Britain, but it was only in 1886 that the British Pound Sterling became the sole legal tender of the archipelago. Third Farthing 1 Farthing Halfpenny 1/1920 Pound 1/960 Pound 1/480 Pound BRITISH COPPER COINS - SOLE LEGAL TENDER Copper Bronze/Copper Copper The Order of St John’s progressive demonetization of the coinage triggered in 1827 with the abolishing of all copper Tari, Grani and Piccioli coins. No copper coins, other than the British Penny, Halfpenny, Farthing and Grain, were considered legal tender after 25 April 1828. The Grain was specifically produced for Malta at the Royal Mint in England, to make up for the disparity in the value of the Farthing (the standard smallest denomination in the Pound system) and local petty transactions. BRITISH GOLD AND SILVER COINS - SOLE LEGAL TENDER A second major step to establish the British currency as the sole legal tender in Malta and Gozo was taken in 1855 when British gold and silver coins were declared as the only means for payment. Nonetheless, the business and banking community continued to make Penny 2 Pence 3 Pence Groat 6 Pence use of gold and silver coins minted by the Order of St John, as well as some other foreign 1/240 Pound 1/120 Pound 1/80 Pound 1/60 Pound 1/40 Pound currencies, particularly the Sicilian Dollar. The situation changed in 1885, when the Italian Bronze/Copper Copper Silver Silver Silver Government announced that the Sicilian Dollar ceased to be legal tender in the Kingdom of Italy. -

The Coinage of Elizabeth I and James I

PRIMARY The Coinage of Elizabeth I and James I £1 = 20 shillings / 1 shilling = 12 pence Under Elizabeth I all coins were made of gold or silver – there were no ‘base metal’ (e.g. copper) coins or paper money like there is today. James I introduced the first copper coinage, the copper farthing. Unlike other coins, copper farthings did not contain their value in metal. It was important for coinage to be worth its FACE VALUE – that is, the amount of gold or silver in a coin should be worth as much as the coin itself claimed to be worth. This is why a silver Crown is so much bigger than a gold Crown – because silver is worth less than gold. There were lots of problems in Tudor and Jacobean times with ‘devaluing’ or ‘debasement’ of the coinage. This was when a coin had less gold or silver in it than it was meant to have. Also, the value of coin went up or down depending on the value of gold or silver at the time. For example – lots of silver being transported from the Americas into Europe meant that silver was worth less than it had been. This lead to some adjustments to the value of coins and their accepted weights. The table on the next few pages gives a rough idea of lowest denomination to highest. For a full range of resources see: shakespeare.org.uk/primaryresources Registered Charity Number 209302 Page 1 PRIMARY The Coinage of Elizabeth I and James I Denomination Elizabeth I James I Metal Farthing Farthing Silver and copper (1/4 pence) (1/4 pence) (under James I only) Halfpenny piece Halfpenny Silver Threefarthing piece None issued -

Historic Coin Finds at the Nickerson Homestead Alan M

Historic Coin Finds at the Nickerson Homestead Alan M. Stahl and Gerry Stahl Four seventeenth-century coins were found in excavation at the William Nickerson Homesite in Chatham during the summers of 2018 and 2019. The excavation was carried out from 2016 to 2019 by Craig Chartier of the Plymouth Archaeological Rediscovery Project under the auspices of the Nickerson Family Association (NFA) on land owned by the Chatham Conservation Foundation (CCF). The archaeological study of the William Nickerson homestead is arguably the most significant Colonial excavation on Cape Cod. It unearthed the first Chatham homestead and produced hundreds of historic artifacts, which shed significant light on the life of Chatham’s founding family. The property where the dig was conducted is now being restored to a public park by CCF, adjacent to the NFA’s museum site. Both the dig and the restoration have been publicly supported by grants from Chatham’s Community Preservation Fund. The archaeological site was the home of William Nickerson and Anne Busby Nickerson, who immigrated to Massachusetts from England in 1637. They moved to Cape Cod in 1661 onto land they had acquired from the Mannamoiett Natives in 1656. The land corresponds roughly to what is now the Town of Chatham. The excavated house appears to have had two rooms in an L-shaped configuration, measuring about 8 meters by 10 meters, with a surrounding wood palisade. Anne died in 1686 and William a few years later. There is no evidence that the house was occupied after that date, although their children settled in the area. -

British Coins

British Coins 1 2 1 † Celtic coinage, early uninscribed coinage, quarter stater, geometric type, unintelligible patterns on both sides, wt. 1.36gms. (S.46), very fine £180-200 2 Early Anglo-Saxon (c.680-710), primary sceat, type C2, diad. bust r., runic letters in r. field, rev. TTII on standard, four crosses around, wt. 0.98gms. (S.779 var.), good very fine £100-120 3 Early Anglo-Saxon (c.695-740), continental sceattas (4), series E (S.790 var.); with hammered silver coins (4), fine to good very fine (8) £300-400 4 Kings of East Anglia, Beonna (c.758), sceat, Efe, BEONNA REX (partly in runic letters), pellet in centre, rev. large cross with E F E in angles and small cross at centre, wt. 0.95gms. (S.945; N.430), minor weakness otherwise good very fine, very rare £3000-3500 5 6 5 † Danelaw (c.898-915), Viking coinage of York, Cnut, patriarchal cross, rev. CVNNETI, small cross and pellets (S.993; N.501), in plastic holder, graded by NGC as AU55, about extremely fine and toned £700-900 6 † Danelaw (c.898-915), Viking coinage of York, Cnut, patriarchal cross, rev. CVNNETTI, small cross and pellets (S.993; N.501), in plastic holder, graded by NGC as XF45, good very fine and toned £450-550 7 8 7 † Wessex, Edward the Elder (899-924), penny, two-line type, Cunulf, small cross pattee, rev. CVNV- LFMTO in two lines, crosslets between, trefoil of pellets above and below (S.1087; N.649), small chip in edge, otherwise almost extremely fine £250-350 8 † Eadgar (959-975), penny, small cross, Eanulf, E.ADG.A.RREX, rev. -

The Coinages of Henry Viii and Edward Vi in Henry's Name

THE COINAGES OF HENRY VIII AND EDWARD VI IN HENRY'S NAME By C. A. WHITTON PART I. INTRODUCTION THE ensuing papers are intended to supplement Brooke's account of the coins of this period, leaving the divisions of them save for some necessary changes in the practical form which he devised. The general plan is to show, after a brief historical survey, each metal in each denomination at the several mints as a complete series, except in the case of the Bristol mint which it seemed desirable to treat separately. Thus the papers will consist of four sections: 1. This introduction, mainly historical, together with a synoptic chart of the various mints and mint accounts. 2. Gold of London including Southwark: (a) Sovereigns of each coinage; (b) Half-sovereigns, and the Sovereign and Half-sove- reigns of Edward VI's coinage in Henry's name; (c) Crowns and Half-crowns of the Double Rose, including those of Edward in Henry's name; (d) Angels of all three coinages of Henry and George Nobles, and their fractions. 3. Silver: (a) First and Second Coinages of London; (b) Ecclesi- astical Coinage; (c) Base Coinage including that of Edward in Henry's name, including coins of the Tower, Southwark, Durham House, Canterbury, and York. 4. Gold and silver of Bristol. In both gold and silver some incidental mention will be made of the early coinages in Edward's name also. The dates of the coinages are: First Coinage, 1509-26; Second Coinage, 1526-44; Base Coinage, 1544-7; Edward's so-called First Coinage, chiefly in Henry's name, 1547-51. -

Coins of Henry VIII

Dr. Richard Kelleher Coins of the Department of Coins and Medals, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge Tudors and Stuarts Henry VIII Part 3 Introduction In the previous two instalments of Fig.1. St this series on the coins of the Tudor and George’s Stuart monarchs I focussed on the first Chapel, and second coinages of Henry VIII. In Windsor Castle. this month’s article I look at the final Burial place of years of Henry’s reign and the disastrous the kings Henry third coinage in which the king author- VI, Edward IV, ised the debasement of the country’s Henry VII, Henry money in a move that would take a gen- VIII, Charles I, eration to remedy. George III, George IV, Henry VIII – The Final Years William IV, (1544-47) Edward VII, In the final three years of Henry’s George V, and life, which coincided with the period of George VI. his third coinage, the great matters of state centred around dynastic concerns and England’s relations with her near- est neighbours Scotland and France. His sixth wife Catherine Parr had helped reconcile Henry with his daughters Fig.2. The fate of Mary and Elizabeth who, by an Act of the Cluniac Priory Parliament of 1543, were now in line at Castle Acre in of succession after Edward. In these Norfolk was typical final years Henry became obese and of the religious suffered with puss-filled boils, and pos- houses of England sibly gout, ailments that resulted from and Wales. It the leg wound he sustained in a jousting was dissolved in accident in 1536. -

The Attribution of the Thistle-Head and Mullet Groats

THE ATTRIBUTION OF THE THISTLE-HEAD AND MULLET GROATS By IAN STEWART SINCE there still appear to be doubts concerning the period of issue of the above coinage of base groats, half-groats, and pence, an attempt is here made to collate the published details on the subject, so as to show that the issue does not belong to the early years of James V, but to the period of about 1470 in the reign of James III. FIG. 1. FIG. 2. FIG. 3. A description of the pieces is as follows: Groat (Fig. 1) Obv. Bust three-quarters right, crowned in surcoat and armour, surrounded by a tressure of eight or nine arcs ; JACOBUS DEI GR.A R.EX SCOTOR.UM or similar; crown of five lis. Rev. Floriate cross fourchee, with thistle heads and mullets of six points in alternate angles; large or small mullets; VIL LAE DINB UR.G or similar; mm. usually a plain cross, sometimes fleury. Stops always single or double saltires. Half-groat (Fig. 2) almost exactly as groat; one with crown of three lis. Penny (Fig. 3) Obv. Crowned bust facing. Rev. Foliated cross fourchee, with slipped trefoils, sometimes approaching quatre- foils, in angles. The cross fourchee connects the pennies with the higher values. The half-groats and pennies are very rare. Early writers on the Scottish coinage all seem to have placed the coins under discussion to James V, but no proof is ever advanced and I have been able to find nothing more helpful than statements such as: "These coins are generally considered as the first coinage of this prince, and I believe correctly, for the open crown and the absence of the numeral, would render it far more likely they were struck in the early than in the later part of this reign (James V).