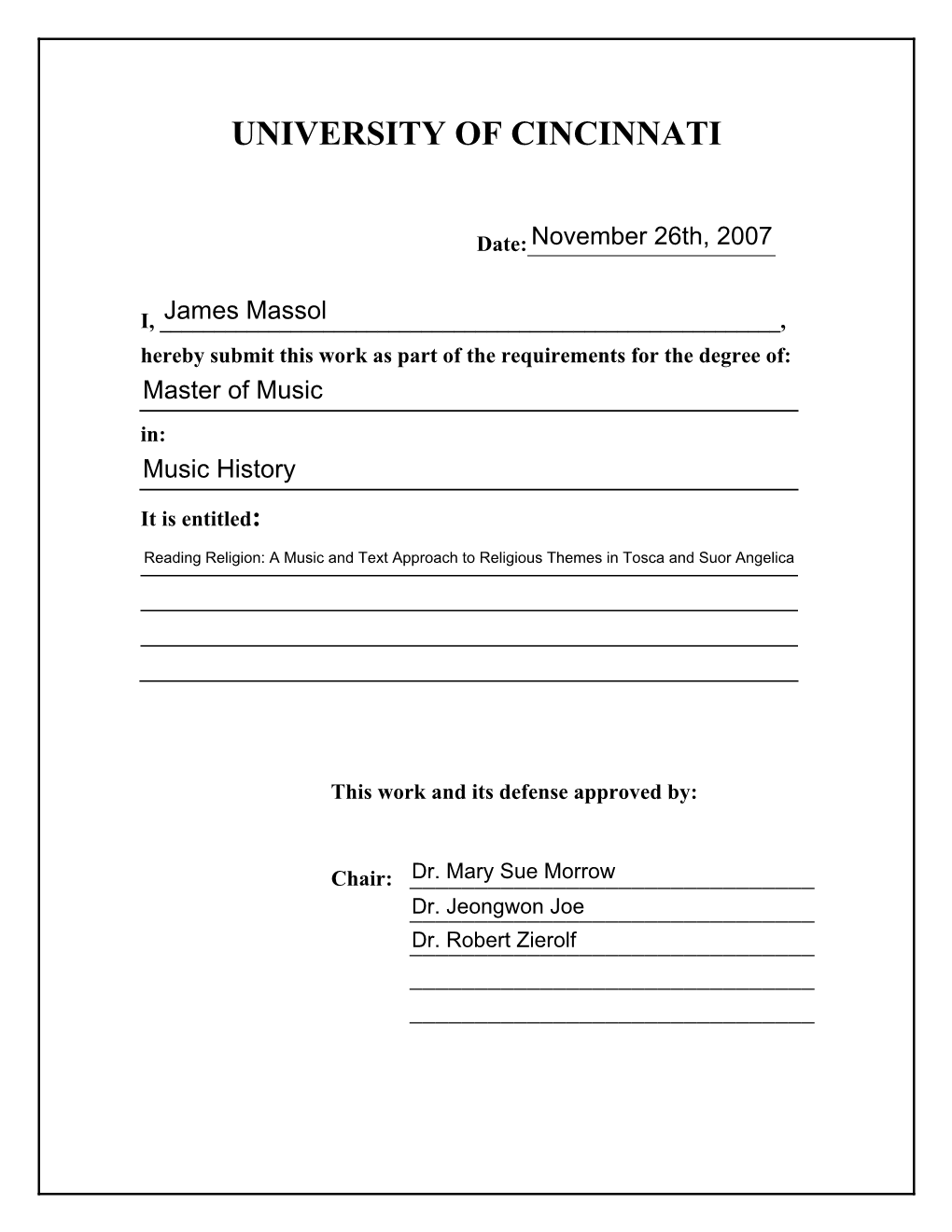

University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domestic Train Reservation Fees

Domestic Train Reservation Fees Updated: 17/11/2016 Please note that the fees listed are applicable for rail travel agents. Prices may differ when trains are booked at the station. Not all trains are bookable online or via a rail travel agent, therefore, reservations may need to be booked locally at the station. Prices given are indicative only and are subject to change, please double-check prices at the time of booking. Reservation Fees Country Train Type Reservation Type Additional Information 1st Class 2nd Class Austria ÖBB Railjet Trains Optional € 3,60 € 3,60 Bosnia-Herzegovina Regional Trains Mandatory € 1,50 € 1,50 ICN Zagreb - Split Mandatory € 3,60 € 3,60 The currency of Croatia is the Croatian kuna (HRK). Croatia IC Zagreb - Rijeka/Osijek/Cakovec Optional € 3,60 € 3,60 The currency of Croatia is the Croatian kuna (HRK). IC/EC (domestic journeys) Recommended € 3,60 € 3,60 The currency of the Czech Republic is the Czech koruna (CZK). Czech Republic The currency of the Czech Republic is the Czech koruna (CZK). Reservations can be made SC SuperCity Mandatory approx. € 8 approx. € 8 at https://www.cd.cz/eshop, select “supplementary services, reservation”. Denmark InterCity/InterCity Lyn Recommended € 3,00 € 3,00 The currency of Denmark is the Danish krone (DKK). InterCity Recommended € 27,00 € 21,00 Prices depend on distance. Finland Pendolino Recommended € 11,00 € 9,00 Prices depend on distance. InterCités Mandatory € 9,00 - € 18,00 € 9,00 - € 18,00 Reservation types depend on train. InterCités Recommended € 3,60 € 3,60 Reservation types depend on train. France InterCités de Nuit Mandatory € 9,00 - € 25,00 € 9,00 - € 25,01 Prices can be seasonal and vary according to the type of accommodation. -

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

Verdi Falstaff

Table of Opera 101: Getting Ready for the Opera 4 A Brief History of Western Opera 6 Philadelphia’s Academy of Music 8 Broad Street: Avenue of the Arts Con9tOperae Etiquette 101 nts 10 Why I Like Opera by Taylor Baggs Relating Opera to History: The Culture Connection 11 Giuseppe Verdi: Hero of Italy 12 Verdi Timeline 13 Make Your Own Timeline 14 Game: Falstaff Crossword Puzzle 16 Bard of Stratford – William Shakespeare 18 All the World’s a Stage: The Globe Theatre Falstaff: Libretto and Production Information 20 Falstaff Synopsis 22 Meet the Artists 23 Introducing Soprano Christine Goerke 24 Falstaff LIBRETTO Behind the Scenes: Careers in the Arts 65 Game: Connect the Opera Terms 66 So You Want to Sing Like an Opera Singer! 68 The Highs and Lows of the Operatic Voice 70 Life in the Opera Chorus: Julie-Ann Whitely 71 The Subtle Art of Costume Design Lessons 72 Conflicts and Loves in Falstaff 73 Review of Philadelphia’s First Falstaff 74 2006-2007 Season Subscriptions Glossary 75 State Standards 79 State Standards Met 80 A Brief History of 4 Western Opera Theatrical performances that use music, song Music was changing, too. and dance to tell a story can be found in many Composers abandoned the ornate cultures. Opera is just one example of music drama. Baroque style of music and began Claudio Monteverdi In its 400-year history opera has been shaped by the to write less complicated music 1567-1643 times in which it was created and tells us much that expressed the character’s thoughts and feelings about those who participated in the art form as writers, more believably. -

Rapporto Annuale Di Bilancio 2013(.Pdf — 8.85

Rapporto annuale di bilancio 2013 Indice Indice 4 Lettera del Presidente 8 Il Gruppo Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane: solide basi per un viaggio da protagonisti IMPRESA E MERCATO Scelte giuste per sfidare il futuro . 10 LIBERALIZZAZIONE Sviluppo senza frontiere . 18 Rapporto annuale GOVERNANCE Nuovi modelli di business . 20 di bilancio PERSONE Il nostro valore aggiunto . 22 2013 26 Economics e investimenti CONSOLIDAMENTO E SVILUPPO Le basi per crescere . 28 LA STRUTTURA Settori operativi del Gruppo . 32 INVESTIMENTI Efficienza e innovazione continua . 60 66 Il nostro impegno IL PIANO INDUSTRIALE 2014-2017 Integrazione modale, logistica specializzata e sviluppo internazionale . 68 ATTIVITÀ INTERNAZIONALE Continuare a essere protagonisti . 78 IL CLIENTE Sicurezza, qualità, informazione . 82 INNOVAZIONE E SVILUPPO Tecnologie da primato . 106 AMBIENTE E SOCIETÀ Responsabilità ed etica, i nostri valori . 108 112 La Fondazione FS Italiane NASCE LA FONDAZIONE FS ITALIANE Un patrimonio di tutti . 114 Lettera del Presidente 66 Il nostro impegno Lettera IL PIANO INDUSTRIALE 2014-2017 del Presidente Integrazione modale, logistica specializzata e sviluppo internazionale . 68 ATTIVITÀ INTERNAZIONALE Continuare a essere protagonisti . 78 IL CLIENTE Sicurezza, qualità, informazione . 82 INNOVAZIONE E SVILUPPO Tecnologie da primato . 106 AMBIENTE E SOCIETÀ Responsabilità ed etica, i nostri valori . 108 Anche per l’esercizio 2013 il Gruppo Ferrovie Il Piano prevede, nel quadriennio, una crescita dello Stato Italiane conferma il percorso di cre- dei ricavi fino a 9,5 miliardi di euro (rispetto agli scita avviato sin dal 2007 e, per il sesto anno 8,2 miliardi nel 2012). Tra i suoi principali obiettivi consecutivo, il trend positivo del risultato netto un tasso medio di crescita dei ricavi del 3,5% 112 La Fondazione FS Italiane di esercizio che cresce di oltre il 20% rispetto all’anno, atteso in particolare dai ricavi dei servizi al 2012 (460 milioni di euro rispetto a 381 mi- di trasporto, sia ferro sia gomma, che si stima NASCE LA FONDAZIONE FS ITALIANE lioni di euro). -

Travelglo-Europe-By-Rail-2020-Au.Pdf

Issue 1 Europe By Rail 2020 Prices from $ * 235per day travelglo.com.au All the essentials you need At TravelGlo, we don't just know what travellers That's why we’ve worked hard to recreate the real want, we know how to connect and enable you joy that is taking you along Europe’s most revealing to discover the world. We don't just make tours, routes and railways. Where the journey becomes we craft adventures that will last a lifetime. part of the destination, go deeper and learn about And we don't just take you from A-to-B, we take the cultures of the incredible places other travellers care of the details so you can live in the now. may never achieve. Do more than just see. Go Our job is to handle the planning, your job is further. Delight your senses. And adopt whatever to unlock a sense of freedom and surprise. pace you want, to create your own adventure. 2 Europe By Rail 2020 What’s included for you? Your Itineraries Your Accommodation You choose the destination and itinerary and Rest easy knowing every 3 or 4-star hotel we will take care of the rest. Experience the you stay in is hand-picked, so you can get the must-sees of Europe without worrying about most out of each destination. Often centrally a thing. Built with your feedback in mind, our located to maximise your experience, carefully crafted itineraries create magic moments with warm standards of service and comfort, that will inspire you in ways you never imagined. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

San Diego Symphony Orchestra Puccini's

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA PUCCINI’S GLORIOUS MASS A Jacobs Masterworks Concert Speranza Scappucci, conductor March 22 and 23, 2019 FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN Symphony No. 88 in G Major Adagio – Allegro Largo Menuetto: Allegretto Allegro con spirito INTERMISSION GIACOMO PUCCINI Messa di Gloria Kyrie Gloria Credo Sanctus – Benedictus Agnus Dei Leonardo Capalbo, tenor Daniel Okulitch, baritone Michael Sumuel, bass San Diego Master Chorale Symphony No. 88 in G Major FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN Born March 31, 1732, Rohrau (Austria) Died May 31, 1809, Vienna Haydn spent 30 years as Kapellmeister to the Esterhazy family at their estates on the plain east of Vienna. If, as Haydn observed, that isolation forced him “to become original,” it also had the unfortunate effect of cutting him off from mainstream European musical life. Only gradually did his extraordinary achievement with the symphony and string quartet become known to musicians across Europe. By the 1780s, when Haydn was in his third decade with the Esterhazys, his prince finally allowed him to accept commissions from outside, and suddenly he had many requests for symphonies. For a concert series in Paris, he wrote his Symphonies No. 82-87 (known as the “Paris symphonies”), and for his two trips to England he composed his final twelve symphonies (Nos. 93-104), inevitably known as the “London symphonies.” Between these two great cycles, Haydn composed five individual symphonies, probably all of them written with Parisian audiences in mind. He wrote the first two, Nos. 88 and 89, in 1787, at exactly the same moment Mozart was composing Don Giovanni in Vienna. -

View the Program!

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

Brochure.Pdf

PAID Standard Presorted Presorted U.S. Postage Postage U.S. Permit #1608 Permit Baltimore, MD Baltimore, Graduation is approaching! Celebrate this milestone and significant achievement with The Ohio State University Alumni Association’s trip for graduating seniors, Classic Europe. UP TO $200 CLASSIC EUROPE This comprehensive tour offers the chance to visit some of the world’s UNLEASH YOUR INNER ADVENTURER. must-see destinations before settling down into a new job or graduate school. It offers the opportunity for fun, hassle-free travel with other graduates, insights into other people, places and cultures – a source of personal enrichment, SAVE experiences that broaden one’s worldview and provide an advantage in today’s global job market - a vacation to remember and a reward for all the hard work. Travelers see amazing sites, such as Big Ben, the Eiffel Tower, and the Roman Forum on this 12-day, 4-country exploration and can add a 5-day extension to relax in the Greek Isles and explore ancient Athens. Past travelers have commented, “This was a trip of a life-time” – “I learned a lot from other cultures and definitely grew as a person” and “Not only was this a vacation, it was a wake-up call to see the world!” Travelers can feel confident that they will get the most out of their time in Europe with the aid of a private tour director and local city historians. Education does not stop after graduation, it is a life-long process and travel is a fantastic way to augment one’s knowledge. After reviewing the information, we hope you’ll agree – this exciting adventure is the perfect way to celebrate! Best regards, Debbie Vargo OR VISIT WWW.AESU.COM/OSU-GRADTRIP VISIT OR FOR DETAILS OR TO BOOK, CALL 1-800-852-TOUR CALL BOOK, TO OR DETAILS FOR EARLY BIRD DISCOUNT - EARLY DECEMBER 3, 2019 IN FULL BY BOOK AND PAY Longaberger Alumni House Alumni Longaberger River Road 2200 Olentangy Ohio 43210 Columbus, Director, Alumni Tours The Ohio State University Alumni Association, Inc. -

Sailing on Seas of Uncertainties: Late Style and Puccini's Struggle for Self

International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 2008 3(1): 77Á95. # The Authors Sailing on seas of uncertainties: late style and Puccini’s struggle for self-renewal By AMIR COHEN-SHALEV Abstract The popularity of Puccini’s melodramatic operas, often derided by ‘‘serious’’ musicologists, has hindered a more rounded evaluation of his attempt at stylistic change. This paper offers a novel perspective of life- span creativedevelopment in order to move the discussion of Puccini beyond the dichotomy of popular versus high-brow culture. Tracing the aspects of gradual stylistic change that began in The Girl from the Golden West (1910) through the three operas of Il Trittico: Il Tabarro, Suor Angelica, and Gianni Schicchi (1918Á1919), the paper then focuses on Puccini’s last opera, Turandot (1926), as exemplifying a potential turn to a reflexive, philosophical style which is very different from the melodramatic, sentimentalist style generally associated with his work. In order to discuss this change as embodying a turn to late style, the paper identifies major stylistic shifts as well as underlying themes in the work of Puccini. The paper concludes by discussing the case of Puccini as a novel contribution to the discussion of lateness in art, until now reserved to a selected few ‘‘old Masters.’’ Keywords: Puccini, late style, life-span development, creativity. Amir Cohen-Shalev, Department of Gerontology, University of Haifa, Israel. 77 International Journal of Ageing and Later Life Beloved and popular, the operas of Giacomo Puccini have at the same time been derided by more ‘‘serious’’ musicologists as the product of a decadent, bourgeois society (Greenwald 1993). -

Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 Is Approved in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

DEVELOPING THE YOUNG DRAMATIC SOPRANO VOICE AGES 15-22 By Monica Ariane Williams Bachelor of Arts – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1993 Master of Music – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2020 Copyright 2021 Monica Ariane Williams All Rights Reserved Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas November 30, 2020 This dissertation prepared by Monica Ariane Williams entitled Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music Alfonse Anderson, DMA. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D. Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Dean Linda Lister, DMA. Examination Committee Member David Weiller, MM. Examination Committee Member Dean Gronemeier, DMA, JD. Examination Committee Member Joe Bynum, MFA. Graduate College Faculty Representative ii ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation provides information on how to develop the young dramatic soprano, specifically through more concentrated focus on the breath. Proper breathing is considered the single most important skill a singer will learn, but its methodology continues to mystify multitudes of singers and voice teachers. Voice professionals often write treatises with a chapter or two devoted to breathing, whose explanations are extremely varied, complex or vague. Young dramatic sopranos, whose voices are unwieldy and take longer to develop are at a particular disadvantage for absorbing a solid vocal technique. First, a description, classification and brief history of the young dramatic soprano is discussed along with a retracing of breath methodologies relevant to the young dramatic soprano’s development. -

Il Trittico 301

Recondite Harmony: Il Trittico 301 Recondite Harmony: the Operas of Puccini Chapter 12: Il Trittico: amore, dolore—e buonumore “Love and suffering were born with the world.” [L’amore e il dolore sono nati col mondo] Giacomo Puccini, letter to Luigi Illica, 8 Oct 19121 Puccini’s operatic triptych, Il Trittico, is comprised of the three one-act operas: Il tabarro, a story of illicit love; Suor Angelica, a tale of a nun’s suffering at the loss of her illegitimate child; and Gianni Schicchi, a dark comedy in which both love and loss are given a morbidly humorous twist. The Trittico2 was always intended by the composer to be performed in a single evening, and it will be treated as a tripartite entity in this chapter. The first two editions, from 1918 and 1919, group all three works together, which was at Puccini’s insistence. In an unpublished letter to Carlo Clausetti, dated 3 July 1918, the composer reveals how he clashed with publisher Tito Ricordi over this issue: There remained the question of the editions—that is, [Tito Ricordi] spoke of them immediately and pacified me by saying that they will publish the works together and separately. But I think that he was not truthful because the separated ones will never see the light of day. And what will happen with the enumeration? There will certainly not be two types of clichets [printing plates], one with numbers progressing through the three operas, and the other with numbers for each score, starting from number one. So, he deceived me.3 1 Eugenio Gara.