William Byrd Festival 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHRIST CHURCH LIBRARY NEWSLETTER Volume 7, Issue 3 Trinity 2011

CHRIST CHURCH LIBRARY NEWSLETTER Volume 7, Issue 3 Trinity 2011 ISSN 1756-6797 (Print), ISSN 1756-6800 (Online) The Aeschylus of Richard Porson CATALOGUING ‘Z’ - EARLY PRINTED PAMPHLETS Among the treasures of the library of Christ Church is It is often asserted that an individual is that which an edition of the seven preserved plays of they eat. Whether or not this is true in a literal sense, Aeschylus, the earliest of the great Athenian writers the diet to which one adheres has certain, of tragedy. This folio volume, published in Glasgow, predictable effects on one’s physiology. As a result, 1795, by the Foulis (‘fowls’) Press, a distinguished the food we consume can affect our day to day life in publisher of classical and other works, contains the respect to our energy levels, our size, our Greek text of the plays, presented in the most demeanour, and our overall health. And, also as a uncompromising manner. I propose first to describe result, this affects how we address the world, it this extraordinary volume and then to look at its affects our outlook on life and how we interact with place in the history of classical scholarship. The book others. This is all circling back around so that I can contains a title page in classical Greek, an ancient ask the question: are we also that which we read? To life of Aeschylus in Greek, and ‘hypotheses’ or an extent, a person in their early years likely does summaries of the plays, some in Greek and some in not have the monetary or intellectual freedom to Latin. -

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Savonarola Ebook Free Download

SAVONAROLA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Elbert Hubbard | 38 pages | 10 Sep 2010 | Kessinger Publishing | 9781169194724 | English | Whitefish MT, United States Savonarola PDF Book Subsequently, Florence was governed along more traditional republican lines, until the return of the Medici in In he became prior of the monastery of San Marco. Character and influence Savonarola's religious actions have been compared to those of the later 17th and 18th century Jansenists, although theologically many differences exist. As the Pope himself frankly confessed, it was the Holy League that insisted. This tense situation came to a head on Palm Sunday, , when a mob comprised of approximately people converged on San Marco, where Savonarola acted as prior. Rather, he wanted to correct the transgressions of worldly popes and secularized members of the Papal Curia. Having made many powerful enemies, the Dominican friar and puritan fanatic Girolamo Savonarola was executed on 23 May That when you were chosen for such a grace: how greatly you are favored to have been made worthy of the blessings and felicity promised to you…. Savonarola ultimately proved unsuccessful in stamping out what had been a longstanding facet of Florentine culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, There he began to preach passionately about the Last Days, accompanied by testimony about his visions and prophetic announcements of direct communications with God and the saints. He drew up letters to the rulers of Christendom urging them to carry out this scheme which, on account of the alliance of the Florentines with Charles VIII, was not altogether beyond possibility. The papal delegates , the general of the Dominicans and the Bishop of Ilerda were sent to Florence to attend the trial. -

The Viola Da Gamba Society Journal

The Viola da Gamba Society Journal Volume Nine (2015) The Viola da Gamba Society of Great Britain 2015-16 PRESIDENT Alison Crum CHAIRMAN Michael Fleming COMMITTEE Elected Members: Michael Fleming, Linda Hill, Alison Kinder Ex Officio Members: Susanne Heinrich, Stephen Pegler, Mary Iden Co-opted Members: Alison Crum, Esha Neogy, Marilyn Pocock, Rhiannon Evans ADMINISTRATOR Sue Challinor, 12 Macclesfield Road, Hazel Grove, Stockport SK7 6BE Tel: 161 456 6200 [email protected] THE VIOLA DA GAMBA SOCIETY JOURNAL General Editor: Andrew Ashbee Editor of Volume 9 (2015): Andrew Ashbee, 214, Malling Road, Snodland, Kent ME6 5EQ [email protected] Full details of the Society’s officers and activities, and information about membership, can be obtained from the Administrator. Contributions for The Viola da Gamba Society Journal, which may be about any topic related to early bowed string instruments and their music, are always welcome, though potential authors are asked to contact the editor at an early stage in the preparation of their articles. Finished material should preferably be submitted by e-mail as well as in hard copy. A style guide is available on the vdgs web-site. CONTENTS Editorial iv ARTICLES David Pinto, Consort anthem, Orlando Gibbons, and musical texts 1 Andrew Ashbee, A List of Manuscripts containing Consort Music found in the Thematic Index 26 MUSIC REVIEWS Peter Holman, Leipzig Church Music from the Sherard Collection (Review Article) 44 Pia Pircher, Louis Couperin, The Extant Music for Wind or String Instruments 55 Letter 58 NOTES ON THE CONTRIBUTORS 59 Abbreviations: GMO Grove Music Online, ed. D. -

Chris Church Matters

Chris Church Matters MICHAELMAS TERM 2014 ISSUE 34 Editorial Contents In this Michaelmas edition we welcome our 45th Dean, the Very Revd Professor Dean’s Diary 1 Martyn Percy, who joined us in October after ten years as Principal of Ripon College Cuddesdon. We also say goodbye to our former Dean, Christopher Lewis, and his wife Goodbye from Chrsitopher Lewis 2 Rhona as they retire to the idyllic Suffolk coast. Much has been achieved in this year Cardinal Sins 6 of change, and we celebrate the successes of members past and present in this issue. If you have news of your own which you would like to share with the Christ Church Christ Church Cathedral Choir 8 community, we invite you to make a submission to the next Annual Report – details Cathedral News 9 of this can be found in College News. A new Christ Church website will be launched in the spring, and with this a new Christ Church People: digital platform for Christ Church Matters. If you would like to receive the magazine Phyllis May Bursill 10 digitally, please let us know. Conservation work We wish you a wonderful Christmas and New Year, and hope to see you in 2015. on the Music Collection 12 Simon Offen Leia Clancy Cathedral School 14 Christ Church Association Alumni Relations Officer Vice President and Deputy [email protected] College News 16 Development Director +44 (0)1865 286 598 [email protected] Boat Club News 18 +44 (0)1865 286 075 Association News 19 FORTHCOMING EVENTS Sensible Religion: A Review 29 Event booking forms are available to download at www.chch.ox.ac.uk/development/events/future The Paper Project at Ovalhouse 30 MARCH 2015 APRIL 2015 SEPTEMBER 2015 Robert Hooke’s Micrographia 32 14 March 24-26 April 12 September FAMILY PROGRAMME LUNCH MEETING MINDS: ALUMNI BOARD OF BENEFACTORS GAUDY Who should decide on war? 34 Christ Church WEEKEND IN VIENNA Christ Church Parents of current or former All are invited to join us for 18-20 September Christ Church Gardens 30 students are invited to lunch at three days of alumni activities MEETING MINDS: ALUMNI Christ Church. -

1 Finding Wroth's Loughton Hall SUSIE WEST the Open University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Research Online Finding Wroth’s Loughton Hall SUSIE WEST The Open University Lady Mary Sidney Wroth, daughter of Penshurst Place, Kent, made her marital home at Loughton Hall, Essex, and remained there as a widow until her own death in 1651.1 The house was burnt down in 1836, and little is known of its appearance or history. This is a loss in two major respects. Firstly, as the home of a major literary figure whose work draws heavily on her life, we might expect that the home environment she created was both shaped by and informed her evocation of place and space in her work. This is not to suggest that literary work can be read back into the built environment, but Loughton Hall should take its place amongst the houses within the Sidney circle: Penshurst Place, Wilton House and Houghton Conquest House, for example. There is more to say about its landscape setting. Secondly, Wroth had a role in remodeling the old house, and there is a tantalizing but unproven association with Inigo Jones, known to Wroth from the Court. This provides the second theme for this discussion, the Court and the classical tradition in architecture. The early decades of the seventeenth century in England are distinguished by what might be called a ‘classical turn’ in building, in the form of heightened awareness of and interest in the theory and practice of architecture as inherited from Italy and a Roman past. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Pieter-Jan Belder the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book

95308 Fitzwilliam VB vol5 2CD_BL1_. 30/09/2016 11:06 Page 1 95308 The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book Volume 5 Munday · Richardson · Tallis Morley · Tomkins · Hooper Pieter-Jan Belder The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book Volume 5 Compact Disc 1 65’42 Compact Disc 2 58’02 John Munday 1555–1630 Anonymous Thomas Morley 1557 –1602 Anonymous & 1 Munday’s Joy 1’26 18 Alman XX 1’58 1 Alman CLII 1’33 Edmund Hooper 1553 –1621 2 Fantasia III, ( fair weather… ) 3’34 19 Praeludium XXII 0’54 2 Pavan CLXIX 5’48 12 Pakington’s Pownde CLXXVIII 2’14 3 Fantasia II 3’36 3 Galliard CLXX 3’00 13 The Irishe Dumpe CLXXIX 1’24 4 Goe from my window (Morley) 4’46 Thomas Tallis c.1505 –1585 4 Nancie XII 4’41 14 The King’s Morisco CCXLVII 1’07 5 Robin 2’08 20 Felix namque I, CIX 9’08 5 Pavan CLIII 5’47 15 A Toye CCLXIII 0’59 6 Galiard CLIV 2’28 16 Dalling Alman CCLXXXVIII 1’16 Ferdinando Richardson 1558 –1618 Anonymous 7 Morley Fantasia CXXIV 5’37 17 Watkins Ale CLXXX 0’57 6 Pavana IV 2’44 21 Praeludium ‘El. Kiderminster’ XXIII 1’09 8 La Volta (set by Byrd) CLIX 1’23 18 Coranto CCXXI 1’18 7 Variatio V 2’47 19 Alman (Hooper) CCXXII 1’13 8 Galiarda VI 1’43 Thomas Tallis Thomas Tomkins 1572 –1656 20 Corrãto CCXXIII 0’55 9 Variatio VII 1’58 22 Felix Namque II, CX 10’16 9 Worster Braules CCVII 1’25 21 Corranto CCXXIV 0’36 10 Pavana CXXIII 6’53 22 Corrãto CCXXV 1’15 Anonymous Anonymous 11 The Hunting Galliard CXXXII 1’59 23 Corrãto CCXXVI 1’08 10 Muscadin XIX 0’41 23 Can shee (excuse) CLXXXVIII 1’48 24 Alman CCXXVII 1’41 11 Pavana M.S. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

1999 Spring Programme

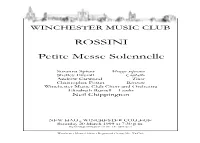

CONCERT DIARY WINCHESTER MUSIC CLUB THE WAYNFLETE SINGERS Come and Sing ... Handel’s Messiah 10th June 1999 7.30pm Conductor: Neil Chippington in Winchester Cathedral 1 May 1999 from 2.00 pm Poulenc Gloria (Performance at 6.00 pm) Fauré Pavane WINCHESTER MUSIC CLUB in Winchester College Chapel Saint-Saëns Symphony No 3 in with a buffet supper in School C minor (Organ) afterwards Fauré Peléas et Mélisande Details from Mrs R. Halliwell, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra 2 Southend Close, Hursley, S021 2LJ Conductor: David Hill (tel 01962 775584) ROSSINI 2nd July 1999 7.30pm WINCHESTER and COUNTY in Winchester Cathedral MUSIC FESTIVAL Verdi Requiem 8 May 1999 at 7.30 pm Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra in Winchester Cathedral Conductor: David Hill Petite Messe Solennelle Dvorák Stabat Mater Conductor: Francis Wells WINCHESTER MUSIC CLUB 25 November 1999 at 7.30 pm 15 May 1999 at 7.30 pm in Winchester Cathedral in Romsey Abbey Mendelssohn Elijah Susanna Spicer Mezzo soprano Charpentier Te Deum, WMC Choir and Orchestra Shelley Everall Contalto Vivaldi Beatus Vir Conductor: Neil Chippington Handel O Praise the Lord with Andrew Carwood Tenor One Consent Christopher Foster Baritone Conductor: Colin Howard Winchester Music Club Choir and Orchestra Tickets, except where indicated, from Music at Winchester (tel. 01962 977977). Elizabeth Russell Leader Neil Chippington NEW HALL, WINCHESTER COLLEGE Winchester Music Club is affiliated to the National Federation of Music Societies which represents and Saturday 20 March 1999 at 7:30 p.m. supports amateur choirs, orchestras and music By kind permission of the Headmaster promoters throughout the United Kingdom. Winchester Music Club is a Registered Charity No. -

Josquin Des Prez: Master of the Notes

James John Artistic Director P RESENTS Josquin des Prez: Master of the Notes Friday, March 4, 2016, 8 pm Sunday, March 6, 2016, 3pm St. Paul’s Episcopal Church St. Ignatius of Antioch 199 Carroll Street, Brooklyn 87th Street & West End Avenue, Manhattan THE PROGRAM CERDDORION Sopranos Altos Tenors Basses Gaude Virgo Mater Christi Anna Harmon Jamie Carrillo Ralph Bonheim Peter Cobb From “Missa de ‘Beata Virgine’” Erin Lanigan Judith Cobb Stephen Bonime James Crowell Kyrie Jennifer Oates Clare Detko Frank Kamai Jonathan Miller Gloria Jeanette Rodriguez Linnea Johnson Michael Klitsch Michael J. Plant Ellen Schorr Cathy Markoff Christopher Ryan Dean Rainey Praeter Rerum Seriem Myrna Nachman Richard Tucker Tom Reingold From “Missa ‘Pange Lingua’” Ron Scheff Credo Larry Sutter Intermission Ave Maria From “Missa ‘Hercules Dux Ferrarie’” BOARD OF DIRECTORS Sanctus President Ellen Schorr Treasurer Peter Cobb Secretary Jeanette Rodriguez Inviolata Directors Jamie Carrillo Dean Rainey From “Missa Sexti toni L’homme armé’” Michael Klitsch Tom Reingold Agnus Dei III Comment peut avoir joye The members of Cerddorion are grateful to James Kennerley and the Church of Saint Ignatius of Petite Camusette Antioch for providing rehearsal and performance space for this season. Jennifer Oates, soprano; Jamie Carillo, alto; Thanks to Vince Peterson and St. Paul’s Episcopal Church for providing a performance space Chris Ryan, Ralph Bonheim, tenors; Dean Rainey, Michael J. Plant, basses for this season. Thanks to Cathy Markoff for her publicity efforts. Mille regretz Allégez moy Jennifer Oates, Jeanette Rodriguez, sopranos; Jamie Carillo, alto; PROGRAM CREDITS: Ralph Bonheim, tenor; Dean Rainey, Michael J. Plant, basses Myrna Nachman wrote the program notes.