San Diego Symphony Orchestra Puccini's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View the Program!

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

“Turandot” by Giacomo Puccini Libretto (English-Italian) Roles Personaggi

Giacomo Puccini - Turandot (English–Italian) 8/16/12 10:44 AM “Turandot” by Giacomo Puccini libretto (English-Italian) Roles Personaggi Princess Turandot - soprano Turandot, principessa (soprano) The Emperor Altoum, her father - tenor Altoum, suo padre, imperatore della Cina (tenore) Timur, the deposed King of Tartary - bass Timur, re tartaro spodestato (basso) The Unknown Prince (Calàf), his son - tenor Calaf, il Principe Ignoto, suo figlio (tenore) Liù, a slave girl - soprano Liú, giovane schiava, guida di Timur (soprano) Ping, Lord Chancellor - baritone Ping, Gran Cancelliere (baritono) Pang, Majordomo - tenor Pang, Gran Provveditore (tenore) Pong, Head chef of the Imperial Kitchen - tenor Pong, Gran Cuciniere (tenore) A Mandarin - baritone Un Mandarino (baritono) The Prince of Persia - tenor Il Principe di Persia (tenore) The Executioner (Pu-Tin-Pao) - silent Il Boia (Pu-Tin-Pao) (comparsa) Imperial guards, the executioner's men, boys, priests, Guardie imperiali - Servi del boia - Ragazzi - mandarins, dignitaries, eight wise men,Turandot's Sacerdoti - Mandarini - Dignitari - Gli otto sapienti - handmaids, soldiers, standard-bearers, musicians, Ancelle di Turandot - Soldati - Portabandiera - Ombre ghosts of suitors, crowd dei morti - Folla ACT ONE ATTO PRIMO The walls of the great Violet City: Le mura della grande Città Violetta (The Imperial City. Massive ramparts form a semi- (La Città Imperiale. Gli spalti massicci chiudono circle quasi that enclose most of the scene. They are interrupted tutta la scena in semicerchio. Soltanto a destra il giro only at the right by a great loggia, covered with è carvings and reliefs of monsters, unicorns, and rotto da un grande loggiato tutto scolpito e intagliato phoenixes, its columns resting on the backs of a mostri, a liocorni, a fenici, coi pilastri sorretti dal gigantic dorso di massicce tartarughe. -

PARLOPHON Matrix Numbers — 2-9000 to 2-9999: British Discography Compiled by Christian Zwarg for GHT Wien Diese Diskographie Dient Ausschließlich Forschungszwecken

PARLOPHON Matrix Numbers — 2-9000 to 2-9999: British Discography compiled by Christian Zwarg for GHT Wien Diese Diskographie dient ausschließlich Forschungszwecken. Die beschriebenen Tonträger stehen nicht zum Verkauf und sind auch nicht im Archiv des Autors oder der GHT vorhanden. Anfragen nach Kopien der hier verzeichneten Tonaufnahmen können daher nicht bearbeitet werden. Sollten Sie Fehler oder Auslassungen in diesem Dokument bemerken, freuen wir uns über eine Mitteilung, um zukünftige Updates noch weiter verbessern und ergänzen zu können. Bitte senden Sie Ihre Ergänzungs- und Korrekturvorschläge an: [email protected] This discography is provided for research purposes only. The media described herein are neither for sale, nor are they part of the author's or the GHT's archive. Requests for copies of the listed recordings therefore cannot be fulfilled. Should you notice errors or omissions in this document, we appreciate your notifying us, to help us improve future updates. Please send your addenda and corrigenda to: [email protected] master 2-9000 master 2-9001 master 2-9002 master 2-9003 1911.08. D30 AN GBR: London, Beka Record Co. Head Office, 77 City Road, E.C. Where My Caravan Has Rested — Song (Hermann Löhr / Edward Teschemacher) Julian Jones (MD). — (orchestra). Giuseppe Lenghi-Cellini (tenor). master 2-9004 1911.08. D30 AN GBR: London, Beka Record Co. Head Office, 77 City Road, E.C. RIGOLETTO (Giuseppe Verdi / Francesco M. Piave) I/ 1: Questa o quella — Ballata {Duca} Questa o quella Julian Jones (MD). — (orchestra). Giuseppe Lenghi-Cellini (tenor). master 2-9005 1911.08. D30 AN GBR: London, Beka Record Co. -

Giacomo Puccini's LA RONDINE Press Kit

Giacomo Puccini's LA RONDINE Press Kit PRESENTS LA RONDINE Opera in three acts Music by Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Giuseppe Adami First performed March 27, 1917 at the Grand Théâtre de Monte Carlo in Monte Carlo, Monaco. Sung in Italian with English supertitles. Supported, in part, by a grant from the Applied Materials Foundation and a Cultural Affairs Grant from the City of San José. PRESS CONTACT Bryan Ferraro Communications Manager Office (408) 437-2229 Mobile (408) 316-2008 [email protected] operasj.org For additional information go to https://www.operasj.org/about-us/press-room/ CAST IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE YVETTE Maya Kherani BIANCA Katharine Gunnink PRUNIER Mason Gates MAGDA Amanda Kingston LISETTE Elena Galván SUZY Teressa Foss RAMBALDO Trevor Neal GOBIN Dane Suarez RUGGERO Jason Slaydon RABONNIER Babatunde Akinboboye 4 Opera San José ARTISTIC TEAM CONDUCTOR MUSIC STAFF Chistopher Larkin Veronika Agranov-Dafoe STAGE DIRECTOR Victoria Lington Candace Evans SUPERTITLE CUEING SET DESIGNER Nicholas Dold Larry Hancock COSTUME DESIGNER Elizabeth Poindexter LIGHTING DESIGNER Kent Dorsey WIG AND MAKEUP DESIGNER Christina Martin CHOREOGRAPHER Michelle Klaers D’Alo PROPERTIES MASTER Lori Scheper-Kesel TECHNICAL DIRECTOR John Draginoff ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Seamus Ricci PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER Nathan Erwin Brauner ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGERS Rebecca Bradley Rachel Nin ASSISTANT CONDUCTOR Andrew Whitfield La rondine Press Kit 5 1ST VIOLIN Cynthia Baehr, Concertmaster Alice Talbot, Asst. Concertmaster Matthew Szemela Valerie Tisdel Chinh Le Virginia -

The Baritone to Tenor Transition

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 2018 The Baritone to Tenor Transition John White University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation White, John, "The Baritone to Tenor Transition" (2018). Dissertations. 1586. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1586 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TENOR TO BARITONE TRANSITION by John Charles White A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved by: Dr. J. Taylor Hightower, Committee Chair Dr. Kimberley Davis Dr. Jonathan Yarrington Dr. Edward Hafer Dr. Joseph Brumbeloe ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. J. Taylor Hightower Dr. Richard Kravchak Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director of School Dean of the Graduate School December 2018 COPYRIGHT BY John Charles White 2018 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT Many notable opera singers have been virtuosic tenors; Franco Corelli, Plácido Domingo, James King, José Carreras, Ramón Vinay, Jon Vickers, and Carlo Bergonzi. Besides being great tenors, each of these singers share the fact that they transitioned from baritone to tenor. Perhaps nothing is more destructive to the confidence of a singer than to have his vocal identity or voice type challenged. -

Bob & Phyllis Neumann

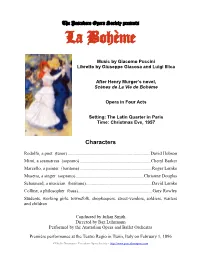

The Pescadero Opera Society presents La Bohème Music by Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica After Henry Murger’s novel, Scènes de La Vie de Bohème Opera in Four Acts Setting: The Latin Quarter in Paris Time: Christmas Eve, 1957 Characters Rodolfo, a poet (tenor) ........................................................................ David Hobson Mimì, a seamstress (soprano) .............................................................. Cheryl Barker Marcello, a painter (baritone) ............................................................... Roger Lemke Musetta, a singer (soprano) ............................................................Christine Douglas Schaunard, a musician (baritone) .......................................................... David Lemke Colline, a philosopher (bass) ................................................................. Gary Rowley Students, working girls, townsfolk, shopkeepers, street-vendors, soldiers, waiters and children Conducted by Julian Smith Directed by Baz Luhrmann Performed by the Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra Première performance at the Teatro Regio in Turin, Italy on February 1, 1896 ©Phyllis Neumann • Pescadero Opera Society • http://www.pescaderoopera.com 2 Synopsis Act I A garret in the Latin Quarter of Paris on Christmas Eve, 1957 The near-destitute artist, Marcello and poet Rodolfo try to keep warm on Christmas Eve by feeding the stove with pages from Rodolfo’s latest drama. They are soon joined by their roommates, Colline, a young philosopher, and Schaunard, a musician who has landed a job bringing them all food, fuel and money. While they celebrate their unexpected fortune, the landlord, Benoit, arrives to collect the rent. Plying the older man with wine, the Bohemians urge him to tell of his flirtations, then throw him out in mock indignation at his infidelity to his wife. Schaunard proposes that they celebrate the holiday at the Café Momus. Rodolfo remains behind to try to finish an article, promising to join them later. -

Giacomo Puccini: Messa Di Gloria Messa Di Gloria

Giacomo Puccini: Messa di Gloria Giacomo Puccini schrieb die "Messa á 4 voci con orchestra", wie der ursprüngliche Titel lautete, als zwanzigjähriger, noch bevor er sein Studium am Mailänder Konservatorium aufnahm. Der Vater war Organist und Chorleiter am Dom seiner Heimatstadt Lucca. Puccini selbst war schon im Alter von 14 Jahren ein versierter Organist, dem so eine Karriere als Kirchenmusiker vorausgesagt wurde. In dieser Familientradition entstand im Jahr 1878 das Credo, das zum Fest des Stadtpatrons St. Paolino aufgeführt wurde. Zwei Jahre später komponierte Puccini die anderen Messteile und vollendete somit sein Jugendwerk. Im Jahr 1880 wurde es in Lucca mit großem Erfolg uraufgeführt. Bemerkenswert ist, dass schon in diesem Frühwerk die Qualitäten seiner späteren Kompositionen klar zu erkennen sind, welche neben einer guten Instrumentierung und Satztechnik vor allem in der Erfindung äußerst suggestiver Melodien liegen. Mit der Oper Manon Lescaut, in der Puccini das Agnus Dei der Messe mitverwendete, gelang ihm im Jahr 1893 ein Werk, das ihm sehr großen Erfolg und finanzielle Unabhängigkeit bescherten, so dass er sich ganz auf dieses Metier konzentrierte. Die Welterfolge wie Madame Butterfly, La Bohème oder Tosca zählen noch heute zu den meistgespielten und geliebten Opern der Theater in der ganzen Welt. Die Messe blieb somit das einzige geistliche Werk des Komponisten, fand auch lange Zeit keine Beachtung und geriet in Vergessenheit. Erst nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg wurde sie in Lucca von Fra Dante del Fiorentino wiederentdeckt. Wegen der großen Ausdehnung des Glorias in der Messe gab er ihr den heute bekannten Namen "Messa di Gloria". Nikolaus Indlekofer Messa di Gloria Kyrie Kyrie eleison! Herr, erbarme Dich unser! Christe eleison! Christus, erbarme Dich unser! Kyrie eleison! Herr, erbarme Dich unser! Gloria Gloria in excelsis Deo. -

Tosca-YPO-Opera-Funtime-Study-Guide.Pdf

Young Patronesses of the Opera Presents: Tosca to the Core: Meeting your benchmarks with the Opera Funtime Created by: Leslie H. Cooper [email protected] Music teacher at Richmond Heights Middle School, Miami, Florida and a member of the Young Patronesses of the Opera. Presented at the YPO Teachers’ Workshop for Miami-Dade County in 2013 as a teachers’ resource to go with using YPO’s Opera Funtime booklets. This is a teacher’s guide with suggested classroom discussions and activities (including KWL) using the Opera Funtime booklets created by Young Patronesses of the Opera (YPO). Opera Funtimes can be found on their website at: www.ypo- miami.org/opera-funtime. More study guides and booklets are available on their website. You can also contact YPO to purchase printed versions (www.ypo-miami.org/contact) ________________________________________________________ I. Start with sharing basic information with the students. a. Who is Giacomo Puccini? Giacomo Puccini, (1858-1924), Italian composer, whose operas blend intense emotion and theatricality with tender lyricism, colorful orchestration, and a rich vocal line. Puccini was born Dec. 22, 1858, in Lucca, the descendant of a long line of local church musicians. In 1880 he wrote a mass, Messa di Gloria, that encouraged his great-uncle to help underwrite his musical education. After studying (1880-83) music at the Milan Conservatory, Puccini wrote his first opera, Le Villi (1884); this brought him a commission to write a second, Edgar (1889), and a lifelong connection with Ricordi, a major music publisher. His third opera, Manon Lescaut (1893), was hailed as the work of a genius. -

02 Istituz Rnd:V

la rondine commedia lirica in tre atti libretto di Giuseppe Adami musica di Giacomo Puccini Teatro La Fenice sabato 26 gennaio 2008 ore 19.00 turni A1-A2 domenica 27 gennaio 2008 ore 15.30 turni B1-B2 martedì 29 gennaio 2008 ore 19.00 turni D1-D2 mercoledì 30 gennaio 2008 ore 17.00 turni C1-C2 giovedì 31 gennaio 2008 ore 19.00 turni E1-E2 domenica 3 febbraio 2008 ore 17.00 fuori abbonamento martedì 5 febbraio 2008 ore 19.00 fuori abbonamento La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2008 1 Arturo Rietti (1863-1943), Giacomo Puccini (1906). Milano, Museo Teatrale alla Scala. La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2008 1 Sommario 5 La locandina 7 «E il passato sembrami dileguar»… di Michele Girardi 13 Giovanni Guanti «Vedranno i posteri che Bijou!» 27 Daniela Goldin Folena La rondine: un libretto inutile? 45 Giacomo Puccini Sogno d’or (1912) 47 La rondine: libretto e guida all’opera a cura di Michele Girardi 101 La rondine: in breve a cura di Maria Giovanna Miggiani 103 Argomento – Argument – Synopsis – Handlung 111 Michela Niccolai Bibliografia 121 Online: Voli pindarici a cura di Roberto Campanella 133 Dall’archivio storico del Teatro La Fenice La rondine, capolavoro beneaugurante a cura di Franco Rossi Locandina per la prima rappresentazione della Rondine al Teatro La Fenice di Venezia. Nei ruoli principali can- tavano: Linda Canneti (Magda), Alba Damonte (Lisette), Manfredi Polverosi (Ruggero), Nello Palai (Prunier). Archivio storico del Teatro La Fenice. la rondine commedia lirica in tre atti libretto di Giuseppe Adami musica di Giacomo Puccini versione 1917 -

Messa a 4 Voci Con Orchestra SC 6

Giacomo PUCCINI Messa a 4 voci con orchestra SC 6 per Soli (TBar/B), Coro (SATB) Ottavino, 2 Flauti, 2 Oboi, 2 Clarinetti 2 Fagotti, 2 Corni, 2 Trombe 3 Tromboni, Oficleide, Timpani 2 Violini, Viola, Violoncello e Contrabbasso herausgegeben von/a cura di/edited by Dieter Schickling Aufführungsmaterial zu/Materiale per l’esecuzione de/Performance material to: Edizione Nazionale delle Opere di Giacomo Puccini Band / Volume III.2 Klavierauszug /Vocal score Riduzioni per canto e pianoforte Paul Horn C Carus 40.645/03 Inhalt/Indice/Contents Vorwort / Introduzione / Foreword III Kyrie (Coro SATB) 2 Gloria Gloria in excelsis Deo (Coro) 8 Laudamus te (Coro) 13 Gratias agimus tibi (Solo T) 16 Gloria in excelsis Deo (Coro) 19 Domine Deus (Coro) 20 Qui tollis peccata mundi (Coro) 21 Quoniam tu solus Sanctus (Coro) 28 Cum Sancto Spiritu (Coro) 30 Credo Credo in unum Deum (Coro) 45 Et incarnatus est (Solo T, Coro) 49 Crucifixus etiam pro nobis (Coro B) 53 Et resurrexit (Coro) 54 Et in Spiritum Sanctum (Coro) 58 Et unam sanctam (Coro) 60 Et vitam venturi saeculi (Coro) 63 Sanctus e Benedictus Sanctus Dominus Deus (Coro) 66 Benedictus qui venit (Solo Bar, Coro) 68 Agnus Dei (Soli TBar, Coro) 70 Anhang/Appendice/Appendix: Gratias agimus tibi 73 Alternativfassung/Versione alternativa/Alternative version Zu diesem Werk liegt folgendes Aufführungsmaterial vor: Band der Edizione Nazionale (Carus 56.001), Partitur (Carus 40.645), Studienpartitur (Carus 40.645/07), Klavierauszug (Carus 40.645/03), komplettes Orchestermaterial (Carus 40.645/19). Il materiale per l’esecuzione è disponibile in volume dell‘Edizione Nazionale (Carus 56.001), partitura d‘orchestra (Carus 40.645), partitura tascabile (Carus 40.645/07), riduzioni per canto e pianoforte (Carus 40.645/03), materiale d’orchestre (Carus 40.645/19). -

Messa Di Gloria Mozart: Symphony No

Summer Concert 2014 Puccini: Messa di Gloria Mozart: Symphony No. 40 in G minor Conductor: Cathal Garvey Soloists: David Butt Philip Ashley Riches Covent Garden Chamber Orchestra Saturday 21st June 2014, 7:30pm St Nicolas Church, Newbury 2 The Programme Sir Charles Hubert Parry Blest pair of Sirens Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 40 in G minor Interval Giacomo Puccini Messa di Gloria Conductor: Cathal Garvey Tenor: David Butt Philip Bass-baritone: Ashley Riches Organist and Rehearsal Accompanist: Steve Bowey Please visit http://www.newburychoral.org.uk/ConcertFeedback/ to give us your feedback on this concert. 3 Programme Notes by Jane Hawker Sir Charles Hubert Parry (1848-1918) Blest pair of Sirens Parry was a composer, music historian and baronet who, as a professor at the newly established Royal College of Music, taught many well-known composers including Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst. A privileged member of the upper classes, Parry was a free-thinker with radical politics and a sensitive disposition. Blest pair of Sirens is a setting of John Milton’s ode At a solemn Musick, a poem extolling the power of ‘voice and verse’. Parry was commissioned by Irish composer Sir Charles Villiers Stanford to write the piece for a concert to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887. It became immediately popular. In 1898, the year that he was made a Knight Bachelor, Parry conducted Newbury Choral Society’s performance of it. In 2011 it was one of three of Parry’s compositions sung at the wedding of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 109, 1989-1990

A GALA OPERATIC EVENING MlRELLA FRENI, soprano and Peter Dvorsky, tenor Members of the J3 Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by John Fiore Presented by the BOSTON OPERA ASSOCIATION Sunday, February 11, 1990, at 8 p.m. Symphony Hall, Boston m ® The Boston Opera Association Mrs. Russell J. Rowell, President Vice-Presidents V.J Hon. Charles Francis Mahoney Anthony D. Ostrom James D. St. Clair David C. Crockett Hon. Lawrence T. Perera Chairman, Board of Overseers Chairman, Board of Directors Robert L. Culver Robert L. Klivans Treasurer Secretary Bruce R. Bengston Michael J. Puzo Assistant Treasurer Assistant Secretary Board of Directors Mrs. Frank G. Allen Dr. Melvin D. Field Dr. Daniel H. Perlman Mr. John T. Bennett, Jr. Mr. Eugene M. Freedman Mr. William S. Reardon Mrs. John M. Bleakie Mr. Martin Gantshar Mr. John Ryan Mrs. Mary Louise Cabot Mr. Gerard A. Glass Mrs. George Lee Sargent Mr. Robert Cahners Mr. Milton L. Glass Mrs. Jacquelyn Scheinbart Mr. William I. Cowin Miss Sally Hurlbut Mr. Robert H. Scott Dean Phyllis Curtin Mrs. Myra Kraft Dr. Lawrence T. Shields Miss Catharine-Mary Donovan Mrs. J. Peter Lyons Mr. Johannes Spanjaard Mr. George Ellison Mr. Donald M. Manzelli Mr. Charles A. Steward Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. Nancy Rice Morss Mrs. Lucius Thayer Board of Overseers Mr. Frank G. Allen, Jr. Mrs. Henry S. Hall, Jr. Mrs. Barbara C. Riley Mr. Robert B.M. Barton Mrs. Henry M. Halvorson Miss Ann Sargent Mrs. Ralph Bradley Mr. Robert Hilliard Mrs. Frederic W. Schwartz Mr. Max Canter Mrs. Robert Douglas Hunter Mrs. Theodore C. Sturtevant Mr.