A NEW ENDING for TOSCA Patricia Herzog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

«Come La Tosca in Teatro»: Una Prima Donna Nel Mito E Nell'attualità

... «come la Tosca in teatro»: una prima donna nel mito e nell’attualità MICHELE GIRARDI La peculiarità della trama di Tosca di Puccini è quella di rappresentare una concatenazione vertiginosa di eventi intorno alla protagonista femminile che è divenuta, in quanto cantante, la prima donna per antonomasia del teatro liri- co. Non solo, ma prima donna al quadrato, perché tale pure nella finzione, oltre che carattere strabordante in ogni sua manifestazione. Giacosa e Illica mutuarono questa situazione direttamente dalla fonte, la pièce omonima di Victorien Sardou, e perciò da Sarah Bernhardt – che aveva ispirato questo ruolo allo scrittore –, anche e soprattutto in occasioni (come vedremo) dove un nodo inestricabile intreccierà la musica all’azione scenica nel capolavoro di Puccini. Stimolati dall’aura metateatrale che pervade il dramma, i due libretti- sti giunsero a inventare un dialogo in due tempi fra i due amanti sfortunati che era solo accennato nell’ipotesto («Joue bien ton rôle... Tombe sur le coup... et fais bien le mort» è la raccomandazione di Floria),1 mentre attendo- no il plotone d’esecuzione fino a quando fa il suo ingresso per ‘giustiziare’ il tenore. E, disattendendo più significativamente la fonte, misero in scena la fu- cilazione, fornendo al compositore un’occasione preziosa per scrivere una marcia al patibolo di grandioso effetto, che incrementa l’atroce delusione che la donna sta per patire. Floria avrebbe dovuto far tesoro della frase di Canio in Pagliacci, «il teatro e la vita non son la stessa cosa», visto che quando arri- va il momento dell’esecuzione cerca di preparare l’amante a cadere bene, «al naturale [...] come la Tosca in teatro» chiosa lui, perché lei, «con scenica scienza» ne saprebbe «la movenza».2 Di questo dialogo a bassa voce non si trova traccia nell’ipotesto: Giacosa e Illica l’inventarono di sana pianta con un colpo di genio. -

Verdi Falstaff

Table of Opera 101: Getting Ready for the Opera 4 A Brief History of Western Opera 6 Philadelphia’s Academy of Music 8 Broad Street: Avenue of the Arts Con9tOperae Etiquette 101 nts 10 Why I Like Opera by Taylor Baggs Relating Opera to History: The Culture Connection 11 Giuseppe Verdi: Hero of Italy 12 Verdi Timeline 13 Make Your Own Timeline 14 Game: Falstaff Crossword Puzzle 16 Bard of Stratford – William Shakespeare 18 All the World’s a Stage: The Globe Theatre Falstaff: Libretto and Production Information 20 Falstaff Synopsis 22 Meet the Artists 23 Introducing Soprano Christine Goerke 24 Falstaff LIBRETTO Behind the Scenes: Careers in the Arts 65 Game: Connect the Opera Terms 66 So You Want to Sing Like an Opera Singer! 68 The Highs and Lows of the Operatic Voice 70 Life in the Opera Chorus: Julie-Ann Whitely 71 The Subtle Art of Costume Design Lessons 72 Conflicts and Loves in Falstaff 73 Review of Philadelphia’s First Falstaff 74 2006-2007 Season Subscriptions Glossary 75 State Standards 79 State Standards Met 80 A Brief History of 4 Western Opera Theatrical performances that use music, song Music was changing, too. and dance to tell a story can be found in many Composers abandoned the ornate cultures. Opera is just one example of music drama. Baroque style of music and began Claudio Monteverdi In its 400-year history opera has been shaped by the to write less complicated music 1567-1643 times in which it was created and tells us much that expressed the character’s thoughts and feelings about those who participated in the art form as writers, more believably. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

296393577.Pdf

Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina 68 (1): 109 - 120 (2011) 109 evolución GeolóGica-GeoMorFolóGica de la cuenca del río areco, ne de la Provincia de Buenos aires enrique FucKs 1, adriana Blasi 2, Jorge carBonari 3, roberto Huarte 3, Florencia Pisano 4 y Marina aGuirre 4 1 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo y Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, LATYR, Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata. E-mail: [email protected] 2 CIC-División Min. Petrología-Museo de La Plata- Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata. 3 CIG-LATYR, CONICET, Museo de La Plata, Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata. 4 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo-Universidad Nacional de la Plata-CONICET, La Plata. resuMen La cuenca del río Areco integra la red de drenaje de la Pampa Ondulada, NE de la provincia de Buenos Aires. Los procesos geomórficos marinos, fluvio-lacustres y eólicos actuaron sobre los sedimentos loéssicos y loessoides de la Formación Pam- peano (Pleistoceno) dejando, con diferentes grados de desarrollo, el registro sedimentario del Pleistoceno tardío y Holoceno a lo largo de toda la cuenca. En estos depósitos se han reconocido, al menos, dos episodios pedogenéticos. Edades 14 C sobre MO de estos paleosuelos arrojaron valores de 7.000 ± 240 y 1.940 ± 80 años AP en San Antonio de Areco y 2.320 ± 90 y 2.000 ± 90 años AP en Puente Castex, para dos importantes estabilizaciones del paisaje, separadas en esta última localidad por un breve episodio de sedimentación. La cuenca inferior en la cañada Honda, fue ocupada por la ingresión durante MIS 1 (Formación Campana), dejando un amplio paleoestuario limitado por acantilados. -

CHAN 3000 FRONT.Qxd

CHAN 3000 FRONT.qxd 22/8/07 1:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 3000(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH David Parry PETE MOOES FOUNDATION Puccini TOSCA CHAN 3000(2) BOOK.qxd 22/8/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) Tosca AKG An opera in three acts Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica after the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou English version by Edmund Tracey Floria Tosca, celebrated opera singer ..............................................................Jane Eaglen soprano Mario Cavaradossi, painter ..........................................................................Dennis O’Neill tenor Baron Scarpia, Chief of Police................................................................Gregory Yurisich baritone Cesare Angelotti, resistance fighter ........................................................................Peter Rose bass Sacristan ....................................................................................................Andrew Shore baritone Spoletta, police agent ........................................................................................John Daszak tenor Sciarrone, Baron Scarpia’s orderly ..............................................Christopher Booth-Jones baritone Jailor ........................................................................................................Ashley Holland baritone A Shepherd Boy ............................................................................................Charbel Michael alto Geoffrey Mitchell Choir The Peter Kay Children’s Choir Giacomo Puccini, c. 1900 -

MODELING HEROINES from GIACAMO PUCCINI's OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MODELING HEROINES FROM GIACAMO PUCCINI’S OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Naomi A. André, Co-Chair Associate Professor Jason Duane Geary, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Allan Clague Assistant Professor Victor Román Mendoza © Shinobu Yoshida All rights reserved 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDECES................................................................................................... iv I. CHAPTER ONE........................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION: PUCCINI, MUSICOLOGY, AND FEMINIST THEORY II. CHAPTER TWO....................................................................................................... 34 MIMÌ AS THE SENTIMENTAL HEROINE III. CHAPTER THREE ................................................................................................. 70 TURANDOT AS FEMME FATALE IV. CHAPTER FOUR ................................................................................................. 112 MINNIE AS NEW WOMAN V. CHAPTER FIVE..................................................................................................... 157 CONCLUSION APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………….162 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................................... -

Media Release

Media Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 13, 2015 Contact: Edward Wilensky (619) 232-7636 [email protected] Soprano Patricia Racette Returns to San Diego Opera “Diva on Detour” Program Features Famed Soprano Singing Cabaret and Jazz Standards Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 7 PM at the Balboa Theatre San Diego, CA – San Diego Opera is delighted to welcome back soprano Patricia Racette for her wildly-acclaimed “Diva on Detour” program which features the renowned singer performing cabaret and jazz standards by Stephen Sondheim, Cole Porter, George Gershwin, and Edith Piaf, among others, on Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 7 PM at the Balboa Theatre. Racette is well known to San Diego Opera audiences, making her Company debut in 1995 as Mimì in La bohème, and returning in 2001 as Love Simpson in Cold Sassy Tree (a role she created for the world premiere at Houston Grand Opera), in 2004 for the title role of Katya Kabanova, and in 2009 as Cio-Cio San in Madama Buttefly. She continues to appear regularly in the most acclaimed opera houses of the world, including the Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera, Los Angeles Opera, and Santa Fe Opera. Known as a great interpreter of Janáček and Puccini, she has gained particular notoriety for her portrayals of the title roles of Madama Butterfly, Tosca, Jenůfa, Katya Kabanova, and all three leading soprano roles in Il Trittico. Her varied repertory also encompasses the leading roles of Mimì and Musetta in La bohème, Nedda in Pagliacci, Elisabetta in Don Carlos, Leonora in Il trovatore, Alice in Falstaff, Marguerite in Faust, Mathilde in Guillaume Tell, Madame Lidoine in Dialogues of the Carmélites, Margherita in Boito’s Mefistofele, Ellen Orford in Peter Grimes, The Governess in The Turn of the Screw, and Tatyana in Eugene Onegin as well as the title roles of La traviata, Susannah, Luisa Miller, and Iphigénie en Tauride. -

11-09-2018 Tosca Eve.Indd

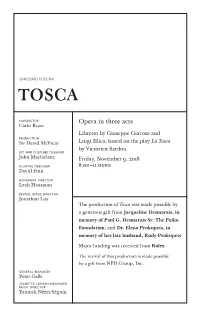

GIACOMO PUCCINI tosca conductor Opera in three acts Carlo Rizzi Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and production Sir David McVicar Luigi Illica, based on the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou set and costume designer John Macfarlane Friday, November 9, 2018 lighting designer 8:00–11:00 PM David Finn movement director Leah Hausman revival stage director Jonathon Loy The production of Tosca was made possible by a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr; The Paiko Foundation; and Dr. Elena Prokupets, in memory of her late husband, Rudy Prokupets Major funding was received from Rolex The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from NPD Group, Inc. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 970th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S tosca conductor Carlo Rizzi in order of vocal appearance cesare angelot ti a shepherd boy Oren Gradus Davida Dayle a sacristan a jailer Patrick Carfizzi Paul Corona mario cavaradossi Joseph Calleja floria tosca Sondra Radvanovsky* baron scarpia Claudio Sgura spolet ta Brenton Ryan sciarrone Christopher Job Friday, November 9, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Sondra Radvanovsky Chorus Master Donald Palumbo in the title role and Fight Director Thomas Schall Joseph Calleja as Musical Preparation John Keenan, Howard Watkins*, Cavaradossi in Puccini’s Tosca Carol Isaac, and Jonathan C. Kelly Assistant Stage Directors Sarah Ina Meyers and Mirabelle Ordinaire Met Titles Sonya Friedman Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Carol Isaac Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes constructed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses gunshot effects. -

Vtctorien SARDOU. VICTORIEN SARDOU

VtCTORIEN SARDOU. m of the motlier country. There are in six. Nevertheless, the character of the the British islands about a hundred and sport provided by our masters is of the eighty packs of fox hounds, besides as best, and American riders who have many more of stag hounds, harriers, formerly gone abroad for the hunting and beagles; and the average number of season now find in their own land abun dogs in a pack is about fifty couples, dant opportunities for indulging in this while the Meadow Brook has but twenty most exhilarating of pastimes. VICTORIEN SARDOU. C iS-• ""' '^'^Sj The foremost of living dramatists— The fatnous Frenchman s^ eventful career^ his long list of successful plays, from '' Pattes de Mouche " {"A Scrap of Paper'') to "Madame Sans-Gine" and his home life at Marly-le-Roi. By Arthur Weyburn Howard. ^ riCTORIEN SARDOU has been at gave him his choice of a profession, and V the head of the French dramatists the young man chose medicine. It was —the most successful play makers in while attached to the Necker Hospital the world—for considerably more than that he wrote his first play—a tragedy a quarter of a century. During that time in blank verse called '' La Reine Alfra.'' he has written nearly sixty plays, which The success this work obtained at a have been translated into every civilized reading encouraged the young author tongue, and he has amassed a fortune, to further efforts in the same direction, unprecedented for a playwright, of though he had no idea, at that time, nearly five millions of francs. -

Writing for Saxophones

WRITING MUSIC FOR SAXOPHONES This is a short information sheet for musicians who wish to create clear, easy to read music for the saxophone. It is based upon my experiences as a jazz saxophone player and the common mistakes that people make when setting out their parts. It covers the basics such as range, transposition, blending, use of altissimo etc. TRANSPOSITION This section is a brief introduction to the concept of transposition. If you already understand how transposing instruments work in principal then please skip to the section entitled 'range' where you can see how to put this information in to practice for particular saxophones. Most saxophones are transposing instruments. This means that the note 'C' on the saxophone does not sound at the same pitch as 'C' on the piano. The common keys which saxophones are made in are B flat (which includes tenor and soprano as well as less common bass and soprillo saxophones) and E flat (alto and baritone, as well as contra bass and sopranino). There are also 'C melody' saxophones, which are made at concert pitch and do not require transposition, however these are less common. When a saxophonist plays a C on a B flat saxophone such as the tenor, the note that comes out sounds at the same pitch as concert B flat (B flat on the piano). Similarly, on an E flat saxophone such as the alto, a C comes out at the same pitch as concert E flat. On a B flat saxophone all the note letter names are one tone higher than they would be on the piano (i.e. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials .....................................................................................................................................