Evelin Lindner, 2015 Puccini's Tosca, and the Journey Toward Respect For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

«Come La Tosca in Teatro»: Una Prima Donna Nel Mito E Nell'attualità

... «come la Tosca in teatro»: una prima donna nel mito e nell’attualità MICHELE GIRARDI La peculiarità della trama di Tosca di Puccini è quella di rappresentare una concatenazione vertiginosa di eventi intorno alla protagonista femminile che è divenuta, in quanto cantante, la prima donna per antonomasia del teatro liri- co. Non solo, ma prima donna al quadrato, perché tale pure nella finzione, oltre che carattere strabordante in ogni sua manifestazione. Giacosa e Illica mutuarono questa situazione direttamente dalla fonte, la pièce omonima di Victorien Sardou, e perciò da Sarah Bernhardt – che aveva ispirato questo ruolo allo scrittore –, anche e soprattutto in occasioni (come vedremo) dove un nodo inestricabile intreccierà la musica all’azione scenica nel capolavoro di Puccini. Stimolati dall’aura metateatrale che pervade il dramma, i due libretti- sti giunsero a inventare un dialogo in due tempi fra i due amanti sfortunati che era solo accennato nell’ipotesto («Joue bien ton rôle... Tombe sur le coup... et fais bien le mort» è la raccomandazione di Floria),1 mentre attendo- no il plotone d’esecuzione fino a quando fa il suo ingresso per ‘giustiziare’ il tenore. E, disattendendo più significativamente la fonte, misero in scena la fu- cilazione, fornendo al compositore un’occasione preziosa per scrivere una marcia al patibolo di grandioso effetto, che incrementa l’atroce delusione che la donna sta per patire. Floria avrebbe dovuto far tesoro della frase di Canio in Pagliacci, «il teatro e la vita non son la stessa cosa», visto che quando arri- va il momento dell’esecuzione cerca di preparare l’amante a cadere bene, «al naturale [...] come la Tosca in teatro» chiosa lui, perché lei, «con scenica scienza» ne saprebbe «la movenza».2 Di questo dialogo a bassa voce non si trova traccia nell’ipotesto: Giacosa e Illica l’inventarono di sana pianta con un colpo di genio. -

296393577.Pdf

Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina 68 (1): 109 - 120 (2011) 109 evolución GeolóGica-GeoMorFolóGica de la cuenca del río areco, ne de la Provincia de Buenos aires enrique FucKs 1, adriana Blasi 2, Jorge carBonari 3, roberto Huarte 3, Florencia Pisano 4 y Marina aGuirre 4 1 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo y Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, LATYR, Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata. E-mail: [email protected] 2 CIC-División Min. Petrología-Museo de La Plata- Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata. 3 CIG-LATYR, CONICET, Museo de La Plata, Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata. 4 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo-Universidad Nacional de la Plata-CONICET, La Plata. resuMen La cuenca del río Areco integra la red de drenaje de la Pampa Ondulada, NE de la provincia de Buenos Aires. Los procesos geomórficos marinos, fluvio-lacustres y eólicos actuaron sobre los sedimentos loéssicos y loessoides de la Formación Pam- peano (Pleistoceno) dejando, con diferentes grados de desarrollo, el registro sedimentario del Pleistoceno tardío y Holoceno a lo largo de toda la cuenca. En estos depósitos se han reconocido, al menos, dos episodios pedogenéticos. Edades 14 C sobre MO de estos paleosuelos arrojaron valores de 7.000 ± 240 y 1.940 ± 80 años AP en San Antonio de Areco y 2.320 ± 90 y 2.000 ± 90 años AP en Puente Castex, para dos importantes estabilizaciones del paisaje, separadas en esta última localidad por un breve episodio de sedimentación. La cuenca inferior en la cañada Honda, fue ocupada por la ingresión durante MIS 1 (Formación Campana), dejando un amplio paleoestuario limitado por acantilados. -

CHAN 3000 FRONT.Qxd

CHAN 3000 FRONT.qxd 22/8/07 1:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 3000(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH David Parry PETE MOOES FOUNDATION Puccini TOSCA CHAN 3000(2) BOOK.qxd 22/8/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) Tosca AKG An opera in three acts Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica after the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou English version by Edmund Tracey Floria Tosca, celebrated opera singer ..............................................................Jane Eaglen soprano Mario Cavaradossi, painter ..........................................................................Dennis O’Neill tenor Baron Scarpia, Chief of Police................................................................Gregory Yurisich baritone Cesare Angelotti, resistance fighter ........................................................................Peter Rose bass Sacristan ....................................................................................................Andrew Shore baritone Spoletta, police agent ........................................................................................John Daszak tenor Sciarrone, Baron Scarpia’s orderly ..............................................Christopher Booth-Jones baritone Jailor ........................................................................................................Ashley Holland baritone A Shepherd Boy ............................................................................................Charbel Michael alto Geoffrey Mitchell Choir The Peter Kay Children’s Choir Giacomo Puccini, c. 1900 -

MODELING HEROINES from GIACAMO PUCCINI's OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MODELING HEROINES FROM GIACAMO PUCCINI’S OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Naomi A. André, Co-Chair Associate Professor Jason Duane Geary, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Allan Clague Assistant Professor Victor Román Mendoza © Shinobu Yoshida All rights reserved 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDECES................................................................................................... iv I. CHAPTER ONE........................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION: PUCCINI, MUSICOLOGY, AND FEMINIST THEORY II. CHAPTER TWO....................................................................................................... 34 MIMÌ AS THE SENTIMENTAL HEROINE III. CHAPTER THREE ................................................................................................. 70 TURANDOT AS FEMME FATALE IV. CHAPTER FOUR ................................................................................................. 112 MINNIE AS NEW WOMAN V. CHAPTER FIVE..................................................................................................... 157 CONCLUSION APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………….162 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................................... -

A NEW ENDING for TOSCA Patricia Herzog

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (1830) A NEW ENDING FOR TOSCA Quasi una fantasia Patricia Herzog Copyright @ 2015 by Patricia Herzog DO YOU KNOW TOSCA? Connaissez-vous la Tosca? In the play from which Puccini took his opera, Victorien Sardou’s La Tosca, Tosca’s lover, the painter Cavaradossi, puts this question to the revolutionary Angelotti who has just escaped from prison. Of course, Angelotti knows Tosca. Everyone knows Tosca. Floria Tosca is the most celebrated diva of her day. Sardou wrote La Tosca for Sarah Bernhardt, the most celebrated actress of her day. Bernhardt opened the play in Paris in 1887 and later took it on the road. Puccini saw her in Italy and was inspired to create his own Tosca, which premiered in Rome in 1900. Today we know the opera and not the play. But do we really know Tosca? The places around Rome and the revolutionary times depicted in Tosca are real. The event on which the Tosca story hinges is Napoleon’s victory at Marengo on June 14, 1800. Tosca sings at Teatro Argentina, Rome’s oldest and most distinguished theater. Cavaradossi paints in the Church of Sant’Andrea della Valle. Chief of Police and arch-villain Scarpia resides in the Farnese Palace. Angelotti escapes, and Tosca later jumps to her death, from the Castel Sant’Angelo. Only Tosca is fictional, although, we might say, she is real enough. There were celebrated divas like her-- independent and in control, artistically, financially, sexually. The first thing we learn about Tosca in the opera is how jealous she is. -

11-09-2018 Tosca Eve.Indd

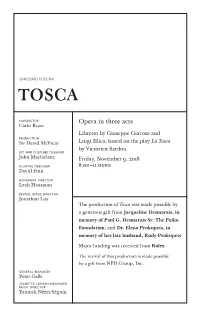

GIACOMO PUCCINI tosca conductor Opera in three acts Carlo Rizzi Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and production Sir David McVicar Luigi Illica, based on the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou set and costume designer John Macfarlane Friday, November 9, 2018 lighting designer 8:00–11:00 PM David Finn movement director Leah Hausman revival stage director Jonathon Loy The production of Tosca was made possible by a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr; The Paiko Foundation; and Dr. Elena Prokupets, in memory of her late husband, Rudy Prokupets Major funding was received from Rolex The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from NPD Group, Inc. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 970th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S tosca conductor Carlo Rizzi in order of vocal appearance cesare angelot ti a shepherd boy Oren Gradus Davida Dayle a sacristan a jailer Patrick Carfizzi Paul Corona mario cavaradossi Joseph Calleja floria tosca Sondra Radvanovsky* baron scarpia Claudio Sgura spolet ta Brenton Ryan sciarrone Christopher Job Friday, November 9, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Sondra Radvanovsky Chorus Master Donald Palumbo in the title role and Fight Director Thomas Schall Joseph Calleja as Musical Preparation John Keenan, Howard Watkins*, Cavaradossi in Puccini’s Tosca Carol Isaac, and Jonathan C. Kelly Assistant Stage Directors Sarah Ina Meyers and Mirabelle Ordinaire Met Titles Sonya Friedman Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Carol Isaac Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes constructed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses gunshot effects. -

“Tosca's Fatal Flaw” Deborah Burton PRIDE, ENVY, GREED: FROM

“Tosca’s Fatal Flaw” Deborah Burton PRIDE, ENVY, GREED: FROM CAIN TO PRESENT JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY April 2011 A few years ago, I was at a performance of Puccini’s opera Tosca in a small farm community where opera was a fairly new commodity. After the second act ended, with the villain Scarpia’s corpse lying center stage, I overheard a young, wide-eyed woman say to her companion, “I knew she was upset, but I didn’t think she’d kill him!” The deaths of all three protagonists in Tosca—the opera diva Floria Tosca, her lover Mario Cavaradossi and the corrupt police chief Baron Vitellio Scarpia—are absolutely necessary because the play it is based upon (La Tosca, written for Sarah Bernhardt by Victorien Sardou in 1887) is written in a quasi-neoclassic style. It aspires, as we shall see, to be a Greek-style tragedy, in which a fatal flaw leads everyone to their doom: in this play, that flaw is Tosca’s sin of envy, or jealousy. 2 Ex. 1: Sarah Bernhard and P. Berton in Sardou’s La Tosca It may seem odd that a work so clearly anti-clerical invokes the concept of sin: Scarpia puts on a show of religious piety, but admits that his lust for Tosca “makes him forget God” while Cavaradossi, the revolutionary hero, is an avowed atheist. Tosca, although she is devout, still manages to carry on an unmarried love affair and commits murder— although she pardons her victim afterwards. And as late as the first printed libretto of the opera (not the play), Cavaradossi cries out, "Ah, there is an avenging God!" [Ah, c'è un Dio vendicator!] instead of the current “Victory!” [Vittoria!] at the climactic moment when he reveals his Napoleonic sympathies. -

The Role of Literary Tradition in the Novelistig

THE ROLE OF LITERARY TRADITION IN THE NOVELISTIG TRAJECTORY OF EMILIA PARDO BAZAN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By ARTHUR ALAN CHANDLER, B. A., M. A, ***** The Ohio State University 1956 Approved by: Adviser Department of Romance Languages ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I should like to thank Professor Stephen Gilman of Harvard University who originally suggested this topic and Professor Gabriel Pradal of The Ohio State University for his guidance through the first three chapters. I am especially grateful to Professors Richard Arraitage, Don L, Demorest and Bruce W. Wardropper, also of The Ohio State University, for their many valuable comments. Professor Carlos Blanco, who graciously assumed direction of this dissertation in its final stages, has provided numerous suggestions for all its chapters. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. Introduction............................ 1 Chapter II. Naturalism in France and Spain......... 10 Chapter III. First Novels............................ 47 Chapter IV. Los pazos de Ulloa and La madre naturaleza 75 Chapter V. Social and Political Themes............. 116 Chapter VI. The Religious Novels.................... 15# Chapter VII. Recapitulation and Conclusion.......... 206 Bibliography (A)..................................... 219 Bibliography (B)..................................... 221 Autobiography........................................ 230 111 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The centenary of the birth of dona Emilia Pardo Bazân (IS5I) has engendered considerable literary criticism regarding the nature and relative importance of her works. Her position in the world of belles lettres has always been partially obscured by the question of Naturalism in Spain. Yet anyone who has read three or four repre sentative novels from her entire literary output realizes that Naturalism is not a dominating feature throughout. -

Three Moments in Western Cultural History

Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 9 September 2010 Tosca’s Prism: Three Moments in Western Cultural History Juan Chattah [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chattah, Juan (2010) "Tosca’s Prism: Three Moments in Western Cultural History," Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic: Vol. 3 : Iss. 1 , Article 9. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol3/iss1/9 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut. REVIEW TOSCA’S PRISM: THREE MOMENTS IN WESTERN CULTURAL HISTORY, EDITED BY DEBORAH BURTON, SUSAN VANDIVER NICASSIO, AND AGOSTINO ZIINO. BOSTON: NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2004. JUAN CHATTAH osca’s Prism is a collection of essays first presented at the “Tosca 2000” conference T held in Rome on 16–18 June 2000. Organized by Deborah Burton, Susan Vandiver Nicassio, and Agostino Ziino, the event celebrated the centennial of the premiere of Giacomo Puccini’s opera Tosca, and the bicentennial of the historic events depicted in Victorien Sardou’s play La Tosca. The conference organizers served as editors of this wide-ranging study, selecting essays that examine the well-chiseled facets of Puccini’s oeuvre. -

Tosca Studyguidev3

By Giacomo Puccini A GUIDE TO THE STUDENT DRESS REHEARSAL SYNOPSIS Act I - In the church of Sant’Andrea della Valle, 1800 the voice of Floria Tosca, Cavaradossi’s lover. Angelotti returns to his hiding spot. Tosca is furious because she heard voices and is convinced that Cavaradossi is cheat- ing on her! Cavaradossi convinces Tosca that he was alone and promises to see her after her opera perform- ance that evening. Tosca leaves and Angelotti comes out of his hiding place. When a cannon is fired, Angelotti and Cavaradossi realize that the police are looking for Angelotti. Cavaradossi suggests that Angelotti hide in the well on his property and the two quickly flee to Cavaradossi’s villa. Baron Scarpia enters the church in Watercolor sketch of The Church of Sant'Andrea della Valle pursuit of Angelotti and deduces that Cavaradossi is from Act I. Painted by Adolfo Hohenstein for the helping the escaped prisoner. Scarpia premiere of Tosca. finds a fan embroidered with the crest of Cesare Angelotti, an escaped political Characters the Marchesa Attavanti. Tosca returns prisoner, dashes into the Church of and Scarpia uses the fan as evidence to Floria Tosca – (soprano) Sant’Andrea della Valle to hide in the convince Tosca of Cavaradossi’s unfaith- A famous Roman singer who is in Attavanti family chapel. At the sound of fulness. Tosca tearfully vows revenge and love with Mario Cavaradossi. the Angelus (a bell that signals a time exits the chapel. As the act closes, Scarpia for late-morning prayer in the Roman Mario Cavaradossi – (tenor) sings of the great pleasure he will have Catholic church), the Sacristan enters to A painter with revolutionary when he destroys Cavaradossi and has pray. -

Music by Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa Based on La Tosca by Victorien Sardou

TOSCA Music by Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa Based on La Tosca by Victorien Sardou TABLE OF CONTENTS ADDITIONAL RESOURCES FOR TEACHERS Thank you to our generous sponsors..2 Preface & Objectives…………………….... 18 Cast of characters…………………... 3 What is Opera Anyway?..................... 19 Brief Overview…………………….. 3 Opera in Not Alone……………………….. 19 Detailed synopsis with musical ex…. 4 Opera Terms………………………………. 20 About the composer………………… 12 Where Did Opera Come From?.................... 21 Historical context………………….. 14 Why Do Opera Singers Sound Like That?.... 22 The creation of the opera………….. 15 How Can I Become an Opera Singer?........... 22 Opera Singer Must-Haves…………………. 23 How to Make an Opera……………………. 24 Jobs in Opera………………………………. 25 Opera Etiquette…………………………….. 26 Discussion Questions………………………. 27 Educational Activities Sponsors…………….. 28 1 PLEASE JOIN US IN THANKING OUR GENEROUS SEASON SPONSORS ! 2 TOSCA First performance on January 14, 1900 at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome, Italy Cast of characters Floria Tosca , a celebrated singer Soprano Mario Cavaradossi, an artist; Tosca’s lover Tenor Baron Scarpia , Chief of Roman police Baritone Cesare Angelotti , former Consul to the Roman Republic Bass A Sacristan Bass Spoletta, a police agent Tenor Sciarrone , a gendarme Bass A Jailer Bass A Shepherd boy Treble Soldiers, police agents, altar boys, noblemen and women, townsfolk, artisans Brief Overview In 1800, the city of Rome was a virtual police state. The ruling Bourbon monarchy was threatened by agitators advocating political and social reform. These included the Republicans, inspired to freedom and democracy by the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and Napoleon. These forces opposed the Royalists who advocated the continuation of the existing monarchy in league with the Roman Catholic Church. -

Tosca: an Opera Thriller

2018 - OSCA release T by Giacomo Puccini diate Salle Wilfrid-Pelletier, Place des Arts e son / 2017 son September 16, 19, 21, and 23, at 7:30 pm ea s imm th For 38 Press Release AN OPERA THRILLER Presented by Musical excerpts / TV Ad Montreal, August 23, 2017 – The Opéra de Montréal opens its 38th season on a grand scale with a work that embodies the very essence of opera: Giacomo Puccini’s passionate melodrama Tosca. Love, jealousy, political intrigue, and constant tension… all the elements of an opera thriller are in place in this new co-production by the Opéra de Montréal and the Cincinnati Opera, given a classic treatment that immerses us in the story’s context and historical setting (Rome, 1800), and features the refined stage direction of Andrew Nienaber, a rising star in the United States. CAST After giving us her moving Butterfly, American soprano Melody Moore returns to the Opéra de Montréal to perform her intense signature role, Floria Tosca. Moore is today one of the world’s finest interpreters of Tosca. Chilean tenor Giancarlo Monsalve, making his company debut, will portray her lover, the painter Mario Cavaradossi. Appearing alongside them, Canadian baritone Gregory Dahl (Aida – 2016) portrays the sinister police chief Scarpia, American bass Valerian Ruminsky (Otello – 2016) sings the Sacristan, and Canadian baritone Patrick Mallette (Les Feluettes – 2016) takes on the role of Cesare Angelotti. Other cast members: Rocco Rupolo (Spoletta), Nathan Keoughan (Sciarrone)— who will also be singing Pink in the revival of Another Brick in the Wall in Cincinnati in 2018—, Max Van Wyck (a Jailer), and Chelsea Rus (a Shepherd).