Three Moments in Western Cultural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

«Come La Tosca in Teatro»: Una Prima Donna Nel Mito E Nell'attualità

... «come la Tosca in teatro»: una prima donna nel mito e nell’attualità MICHELE GIRARDI La peculiarità della trama di Tosca di Puccini è quella di rappresentare una concatenazione vertiginosa di eventi intorno alla protagonista femminile che è divenuta, in quanto cantante, la prima donna per antonomasia del teatro liri- co. Non solo, ma prima donna al quadrato, perché tale pure nella finzione, oltre che carattere strabordante in ogni sua manifestazione. Giacosa e Illica mutuarono questa situazione direttamente dalla fonte, la pièce omonima di Victorien Sardou, e perciò da Sarah Bernhardt – che aveva ispirato questo ruolo allo scrittore –, anche e soprattutto in occasioni (come vedremo) dove un nodo inestricabile intreccierà la musica all’azione scenica nel capolavoro di Puccini. Stimolati dall’aura metateatrale che pervade il dramma, i due libretti- sti giunsero a inventare un dialogo in due tempi fra i due amanti sfortunati che era solo accennato nell’ipotesto («Joue bien ton rôle... Tombe sur le coup... et fais bien le mort» è la raccomandazione di Floria),1 mentre attendo- no il plotone d’esecuzione fino a quando fa il suo ingresso per ‘giustiziare’ il tenore. E, disattendendo più significativamente la fonte, misero in scena la fu- cilazione, fornendo al compositore un’occasione preziosa per scrivere una marcia al patibolo di grandioso effetto, che incrementa l’atroce delusione che la donna sta per patire. Floria avrebbe dovuto far tesoro della frase di Canio in Pagliacci, «il teatro e la vita non son la stessa cosa», visto che quando arri- va il momento dell’esecuzione cerca di preparare l’amante a cadere bene, «al naturale [...] come la Tosca in teatro» chiosa lui, perché lei, «con scenica scienza» ne saprebbe «la movenza».2 Di questo dialogo a bassa voce non si trova traccia nell’ipotesto: Giacosa e Illica l’inventarono di sana pianta con un colpo di genio. -

296393577.Pdf

Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina 68 (1): 109 - 120 (2011) 109 evolución GeolóGica-GeoMorFolóGica de la cuenca del río areco, ne de la Provincia de Buenos aires enrique FucKs 1, adriana Blasi 2, Jorge carBonari 3, roberto Huarte 3, Florencia Pisano 4 y Marina aGuirre 4 1 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo y Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, LATYR, Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata. E-mail: [email protected] 2 CIC-División Min. Petrología-Museo de La Plata- Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata. 3 CIG-LATYR, CONICET, Museo de La Plata, Universidad Nacional de la Plata, La Plata. 4 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo-Universidad Nacional de la Plata-CONICET, La Plata. resuMen La cuenca del río Areco integra la red de drenaje de la Pampa Ondulada, NE de la provincia de Buenos Aires. Los procesos geomórficos marinos, fluvio-lacustres y eólicos actuaron sobre los sedimentos loéssicos y loessoides de la Formación Pam- peano (Pleistoceno) dejando, con diferentes grados de desarrollo, el registro sedimentario del Pleistoceno tardío y Holoceno a lo largo de toda la cuenca. En estos depósitos se han reconocido, al menos, dos episodios pedogenéticos. Edades 14 C sobre MO de estos paleosuelos arrojaron valores de 7.000 ± 240 y 1.940 ± 80 años AP en San Antonio de Areco y 2.320 ± 90 y 2.000 ± 90 años AP en Puente Castex, para dos importantes estabilizaciones del paisaje, separadas en esta última localidad por un breve episodio de sedimentación. La cuenca inferior en la cañada Honda, fue ocupada por la ingresión durante MIS 1 (Formación Campana), dejando un amplio paleoestuario limitado por acantilados. -

CHAN 3000 FRONT.Qxd

CHAN 3000 FRONT.qxd 22/8/07 1:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 3000(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH David Parry PETE MOOES FOUNDATION Puccini TOSCA CHAN 3000(2) BOOK.qxd 22/8/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) Tosca AKG An opera in three acts Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica after the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou English version by Edmund Tracey Floria Tosca, celebrated opera singer ..............................................................Jane Eaglen soprano Mario Cavaradossi, painter ..........................................................................Dennis O’Neill tenor Baron Scarpia, Chief of Police................................................................Gregory Yurisich baritone Cesare Angelotti, resistance fighter ........................................................................Peter Rose bass Sacristan ....................................................................................................Andrew Shore baritone Spoletta, police agent ........................................................................................John Daszak tenor Sciarrone, Baron Scarpia’s orderly ..............................................Christopher Booth-Jones baritone Jailor ........................................................................................................Ashley Holland baritone A Shepherd Boy ............................................................................................Charbel Michael alto Geoffrey Mitchell Choir The Peter Kay Children’s Choir Giacomo Puccini, c. 1900 -

MODELING HEROINES from GIACAMO PUCCINI's OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MODELING HEROINES FROM GIACAMO PUCCINI’S OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Naomi A. André, Co-Chair Associate Professor Jason Duane Geary, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Allan Clague Assistant Professor Victor Román Mendoza © Shinobu Yoshida All rights reserved 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDECES................................................................................................... iv I. CHAPTER ONE........................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION: PUCCINI, MUSICOLOGY, AND FEMINIST THEORY II. CHAPTER TWO....................................................................................................... 34 MIMÌ AS THE SENTIMENTAL HEROINE III. CHAPTER THREE ................................................................................................. 70 TURANDOT AS FEMME FATALE IV. CHAPTER FOUR ................................................................................................. 112 MINNIE AS NEW WOMAN V. CHAPTER FIVE..................................................................................................... 157 CONCLUSION APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………….162 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................................... -

A NEW ENDING for TOSCA Patricia Herzog

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (1830) A NEW ENDING FOR TOSCA Quasi una fantasia Patricia Herzog Copyright @ 2015 by Patricia Herzog DO YOU KNOW TOSCA? Connaissez-vous la Tosca? In the play from which Puccini took his opera, Victorien Sardou’s La Tosca, Tosca’s lover, the painter Cavaradossi, puts this question to the revolutionary Angelotti who has just escaped from prison. Of course, Angelotti knows Tosca. Everyone knows Tosca. Floria Tosca is the most celebrated diva of her day. Sardou wrote La Tosca for Sarah Bernhardt, the most celebrated actress of her day. Bernhardt opened the play in Paris in 1887 and later took it on the road. Puccini saw her in Italy and was inspired to create his own Tosca, which premiered in Rome in 1900. Today we know the opera and not the play. But do we really know Tosca? The places around Rome and the revolutionary times depicted in Tosca are real. The event on which the Tosca story hinges is Napoleon’s victory at Marengo on June 14, 1800. Tosca sings at Teatro Argentina, Rome’s oldest and most distinguished theater. Cavaradossi paints in the Church of Sant’Andrea della Valle. Chief of Police and arch-villain Scarpia resides in the Farnese Palace. Angelotti escapes, and Tosca later jumps to her death, from the Castel Sant’Angelo. Only Tosca is fictional, although, we might say, she is real enough. There were celebrated divas like her-- independent and in control, artistically, financially, sexually. The first thing we learn about Tosca in the opera is how jealous she is. -

11-09-2018 Tosca Eve.Indd

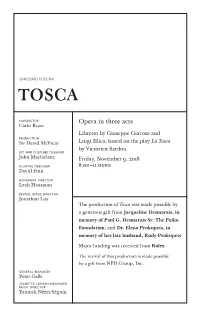

GIACOMO PUCCINI tosca conductor Opera in three acts Carlo Rizzi Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and production Sir David McVicar Luigi Illica, based on the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou set and costume designer John Macfarlane Friday, November 9, 2018 lighting designer 8:00–11:00 PM David Finn movement director Leah Hausman revival stage director Jonathon Loy The production of Tosca was made possible by a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr; The Paiko Foundation; and Dr. Elena Prokupets, in memory of her late husband, Rudy Prokupets Major funding was received from Rolex The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from NPD Group, Inc. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 970th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S tosca conductor Carlo Rizzi in order of vocal appearance cesare angelot ti a shepherd boy Oren Gradus Davida Dayle a sacristan a jailer Patrick Carfizzi Paul Corona mario cavaradossi Joseph Calleja floria tosca Sondra Radvanovsky* baron scarpia Claudio Sgura spolet ta Brenton Ryan sciarrone Christopher Job Friday, November 9, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Sondra Radvanovsky Chorus Master Donald Palumbo in the title role and Fight Director Thomas Schall Joseph Calleja as Musical Preparation John Keenan, Howard Watkins*, Cavaradossi in Puccini’s Tosca Carol Isaac, and Jonathan C. Kelly Assistant Stage Directors Sarah Ina Meyers and Mirabelle Ordinaire Met Titles Sonya Friedman Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Carol Isaac Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes constructed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses gunshot effects. -

Homage to Two Glories of Italian Music: Arturo Toscanini and Magda Olivero

HOMAGE TO TWO GLORIES OF ITALIAN MUSIC: ARTURO TOSCANINI AND MAGDA OLIVERO Emilio Spedicato University of Bergamo December 2007 [email protected] Dedicated to: Giuseppe Valdengo, baritone chosen by Toscanini, who returned to the Maestro October 2007 This paper produced for the magazine Liberal, here given with marginal changes. My thanks to Countess Emanuela Castelbarco, granddaughter of Toscanini, for checking the part about her grandfather and for suggestions, and to Signora della Lirica, Magda Olivero Busch, for checking the part relevant to her. 1 RECALLING TOSCANINI, ITALIAN GLORY IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY As I have previously stated in my article on Andrea Luchesi and Mozart (the new book by Taboga on Mozart death is due soon, containing material discovered in the last ten years) I am no musicologist, just a person interested in classical music and, in more recent years, in opera and folk music. I have had the chance of meeting personally great people in music, such as the pianist Badura-Skoda, and opera stars such as Taddei, Valdengo, Di Stefano (or should I say his wife Monika, since Pippo has not yet recovered from a violent attack by robbers in Kenya; they hit him on the head when he tried to protect the medal Toscanini had given him; though no more in a coma, he is still paralyzed), Bergonzi, Prandelli, Anita Cerquetti and especially Magda Olivero. A I have read numerous books about these figures, eight about Toscanini alone, and I was also able to communicate with Harvey Sachs, widely considered the main biographer of Toscanini, telling him why Toscanini broke with Alberto Erede and informing him that, contrary to what he stated in his book on Toscanini’s letters, there exists one letter by one of his lovers, Rosina Storchio. -

Evelin Lindner, 2015 Puccini's Tosca, and the Journey Toward Respect For

Puccini’s Tosca, and the Journey toward Respect for Equal Dignity for All Evelin Lindner November 26, 2015 New York City Summary This is a story of an opera and how it applies to the need to build a world worth living in, for our children and all beings, and the obstacles on the path to get there. Modern-day topics such as terrorism and gender relations are part of this quest. This text starts with a brief description of the opera, and then addresses its relevance for the transition toward a world that manifests the ideals of the French Revolution of liberté, égalité, and fraternité, a motto that is also at the core of modern-day human rights ideals: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood (and sisterhood).” The opera Yesterday, I had the privilege of seeing the opera Tosca by Giacomo Puccini, at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. It is an opera based on Victorien Sardou’s 1887 French- language dramatic play, La Tosca. In the program leaflet we read: No opera is more tied to its setting than Tosca: Rome, the morning of June 17, 1800, through dawn the following day. The specified settings for each of the three acts – the Church of Sant’Andrea della Valle, Palazzo Farnese, and Castel Sant’Angelo – are familiar monuments in the city and can still be visited today.1 It is a melodramatic piece, containing depictions of torture, murder and suicide. -

Adriana Lecouvreur

CILEA Adriana Lecouvreur • Mario Rossi, cond; Magda Olivero (Adriana Lecouvreur); Giulietta Simionato (La Principessa di Bouillon); Franco Corelli (Maurizio); Ettore Bastianini (Michonnet); Teatro San Carlo Naples Ch & O • IMMORTAL PERFORMANCES 1111/1–2 mono (2 CDs: 142:49) Live: Naples 11/28/1959 MASCAGNI Iris • Olivero de Fabritiis, cond; Magda Olivero (Iris); Salvatore Puma (Osaka); Saturno Meletti (Kyoto); Giulio Neri (Il Cieco); RAI Turin Ch & O • IMMORTAL PERFORMANCES 1111/3–4 mono (2 CDs: 156:05) Live: Turin 9/6/1956 & PUCCINI Manon Lescaut: In quelle trine morbide; Sola perdutto abbandonata (Fulvio Vernizzi, Netherlands RS, 10/31/1966). La rondine: Che il bel sogno (Anton Kerjes, unidentified O, 3/5/1972). ALFANO Risurrezione: Dio pietoso (Elio Boncompagni, RAI Turin O, 1/30/1973). CATALANI Loreley: Amor celeste ebbrezza (Arturo Basile, RAI Turin O, 5/6/1953) VERDI La traviata: Act I, É strano....Ah, fors’è lui....Sempre libera; Magda Olivero, Muzio Giovagnoli, tenor, Ugo Tansini, cond.; RAI Turin O, 1940. Act II, Scene 1: Magda Olivero; Aldo Protti, (Giorgio Germont). Live, Orchestra Radio Netherlands, Fulvio Vernizzi, cond., 6 May 1967. Act II – Amami Alfredo! Magda Olivero; Ugo Tansini cond., 6 May 1953 (Cetra AT 0320) Act III Complete • Fulvio Vernizzi, cond; Magda Olivero (Violetta); Doro Antonioli (Alfredo Germont); Aldo Protti (Giorgio Germont). Live, Orchestra Radio Netherlands, 6 May 1967. & PUCCINI Tosca: Vissi d’arte (Ugo Tansini, RAI Turin O, 1940). La bohème: Addio….Donde lieta usci (Fulvio Vernizzi, Netherlands RS, 3/2/1968). Madama Butterfly: Ancora un passo; Un bel di vedremo (Fulvio Vernizzi, Netherlands RS, 3/2/1968 and 12/14/1968) By James Altena March/April 2019 The remarkably long-lived Magda Olivero (1910–2014)—who, incredibly and like the magnificent Russian basso Mark Reizen, sang when in her 90s—is the rare singer for whom an adjective such as “fabled” never grows 1 stale. -

Magda Olivero Last Updated Tuesday, 20 March 2012 07:10

Magda Olivero Last Updated Tuesday, 20 March 2012 07:10 Magda Olivero is March 25, 2010 100 years See the excerpt from the interview on March 20 at the bottom of this page "Given a choice between Callas and Olivero, I'd actually pick Olivero. She has greater warmth and depth and is more moving. -Stefan Zucker, Opera Fanatic magazine "....Bestaat er een Olivero-effect? Ik ga het wel geloven. In ieder geval blijft Magda Olivero een van de grootste opera-wonderen van de afgelopen eeuw. Na haar debuut in 1933 trok zij zich in 1941 terug van het toneel om 19 jaar later terug te keren op verzoek van de componist Cilea, die in haar de ideale Adriana Lecouvreur zag. -Paul Korenhof, Luister januari 1992. Deze opera, en wel met de aria "Del sultano Amuratte" was mijn eerste kennismaking met Magda Olivero. Een kennismaking met een stem die een onuitwisbare indruk op mij maakte. Een uiterst expressieve stem. Olivero is een wonder, een ander woord ken ik er niet voor. Zoals zij met die eigenlijk helemaal niet zo mooie stem een rol weet neer te zetten is ongelooflijk, daar is zij werkelijk uniek in. 1 / 6 Magda Olivero Last Updated Tuesday, 20 March 2012 07:10 Magda Olivero (born in Saluzzo, 25 March 1910), has had a very unique career. She made her debut for the Turin radio in 1932 with Nino Cattozzo's 'I Misteri Dolorosi'. In 1933 she sang Lauretta in Gianni Schicchi at the Teatro Vittorio Emanuele in the same city. Up until 1940, she sang in all the major Italian theatres and was often heard on the Italian national radio EIAR (now RAI). -

MARIO DEL MONACO Mario Del Monaco Belongs

MARIO DEL MONACONACO – A CRITICAL APPROACH BY DANIELE GODOR, XII 2009 INTRODUCTION Mario del Monaco belongselongs to a group of singers whoho aare sacrosanct to many opera listeners.listene Too impressive are the existingexisti documents of his interpretationsations of Otello (no other tenor hasas momore recordings of the role of Otello than Del Monaco who claimed to haveha sung to role 427 times1), Radamdames, Cavaradossi, Samson, Don Josésé and so on. His technique is seenn as the non-plus-ultra by many singersgers aand fans: almost indefatigable – comparable to Lauritz Melchiorlchior in this regard –, with a solid twoo octaveocta register and capable of produciroducing beautiful, virile and ringing sound of great volume. His most importmportant teacher, Arturo Melocchi,, finallyfina became famous throughh DDel Monaco’s fame, and a new schoolscho was born: the so-called Melocchialocchians worked with the techniqueique of Melocchi and the bonus of the mostm well-established exponent of his technique – Mario del Monaco.naco. Del Monaco, the “Otello of the century”” and “the Verdi tenor” (Giancarlo del Monaco)2 is – as tthese attributes suggest – a singer almost above reproach and those critics, who pointed out someme of his shortcomings, were few. In the New York Times, the famous critic Olin Downes dubbed del MonacoM “the tenor of tenors” after del Monacoonaco’s debut as Andrea Chenier in New York.3 Forr manmany tenors, del Monaco was the great idoll and founder of a new tradition: On his CD issued by the Legato label, Lando Bartolini claims to bee a sinsinger “in the tradition of del Monaco”, and even Fabioabio ArmilA iato, who has a totally different type of voice,voi enjoys when his singing is put down to the “tradititradition of del Monaco”.4 Rodolfo Celletti however,wever, and in spite of his praise for Del Monaco’s “oddodd elelectrifying bit of phrasing”, recognized in DelDel MMonaco one of the 1 Chronologies suggest a much lower amount of performances. -

Private Musiksammlung Archiv CD/DVD

Private Musiksammlung Aktualisierung am: 04.09.15 Archiv CD/DVD - Oper Sortierung nach: in CD - mp3 / DVD - MEGP- Formaten 1. Komponisten 2. Werk-Nummer (op.Zahl etc) TA und TR: Daten sind bei „alne“ vorhanden 3. Aufnahmejahr Auskünfte über Mail [email protected] Diese Datei erreichen Sie unter: T und TR: Daten sind bei „EO“ vorhanden http://www.euro-opera.de/T-TA-TR.pdf Auskünfte über Mail in Kürze auch unter: [email protected] http://www.cloud-de.de/~Alne_Musik/ Pacini Pacini LA POETESSA - 2001 Festival Pesaro - - - - - - - - - n O - 21.08.2001 Giovanni Pacini IDROFOBA - (1796 - 1867) - l 'Orchestra Giovanile 01.01.1900 - del Festival Oper 12 - cda1411 TA-an Anna-Maria di Micco, Tiziana Fabricini, Dariusz Machej, Alessandro Codeluppi, Roberto Rizzi Brignoli A Marco Vinco, Rosita Frisani alne 1 CD Pacini La poetessa idrofoba - 2001 Pesaro Annamaria Di Micco - Tiziana Roberto Rizzi Brignoli O - 21.08.2001 Fabbricini - Alessandro Codeluppi - 871,01 Giovanni Pacini - Dariusz Machej - Marco Vinco - Rosita (1796 - 1867) - Dalla beffa il disinganno, Orchestra giovanile 01.01.1900 - ossia La poetessa Frisani - - - - del Festival Oper 12 - cda701 T- Alne 706 1 CD 5 Pacini ALESSANDRO - 2006 London - - - - - - - - - n O - 19.11.2006 Giovanni Pacini NELL'INDIE - (1796 - 1867) - 01.01.1900 - Oper 31 - cda1411 TA-an Bruce Ford, Jannifer Larmore, Laura Claycomb, Dean robinson, Mark, Wilde. David Parry A OR 3 CD Pacini Alessandro nelle Indie - 2006 London Bruce Ford - Jennifer Larmore - Laura David Parry O - 19.11.2006 Claycomb - Dean Robinson